In our recent article about the differences between East Coast and West Coast synthesis, we explored the early history of modular synthesizer design, highlighting the early work of engineers Robert Moog and Donald Buchla. Famously, each of them invented a modular synthesizer at roughly the same time in the mid-1960s; however, each of them had vastly different musical and commercial concerns, which significantly influenced the music produced with their systems. Quite broadly speaking, Moog's instruments typically were used to produce more "conventional music," while Buchla's instruments leaned more toward the "experimental." Soon after its introduction, Moog's methodology became considerably more influential on both popular music and on other instrument designers, and as such, most synthesizers produced up until the current day borrow much more from Moog's approach than they do Buchla's.

So to recap, what is West Coast synthesis? So-called "West Coast synthesis" is perhaps best understood as an instrument design approach pioneered by Don Buchla starting in the 1960s; this approach privileges experimental means of soundmaking and user interaction, often bringing into question the nature of the compositional process altogether. Many definitions of West Coast synthesis also go on to discuss the importance of specific esoteric synthesis tools absent from Moog's instruments, such as complex oscillators, lowpass gates, function generators, touchplate keyboards, and so on. But are these distinctions fundamentally true? Or is it just a convenient, simple way of pointing out differences between Buchla's approach and Moog's?

Before continuing, I'll state that I'm not sure that our current use of the terms "East Coast" and "West Coast" is terribly useful, but given their prevalence, I suspect that these terms are here to stay. And moreover, I do believe that there are plenty of interesting differences between Moog and Buchla's instruments that are well worth consideration and conversation...so perhaps, with a little bit of thought and effort, we can pivot those terms toward a more fun/productive sort of conversation about instrument design.

All that said, be sure to check out the first article in this series for background info, and then let's pick up where we left off: the introduction of Buchla's 200 Series.

The Electric Music Box: the Advent of the Buchla 200 Series

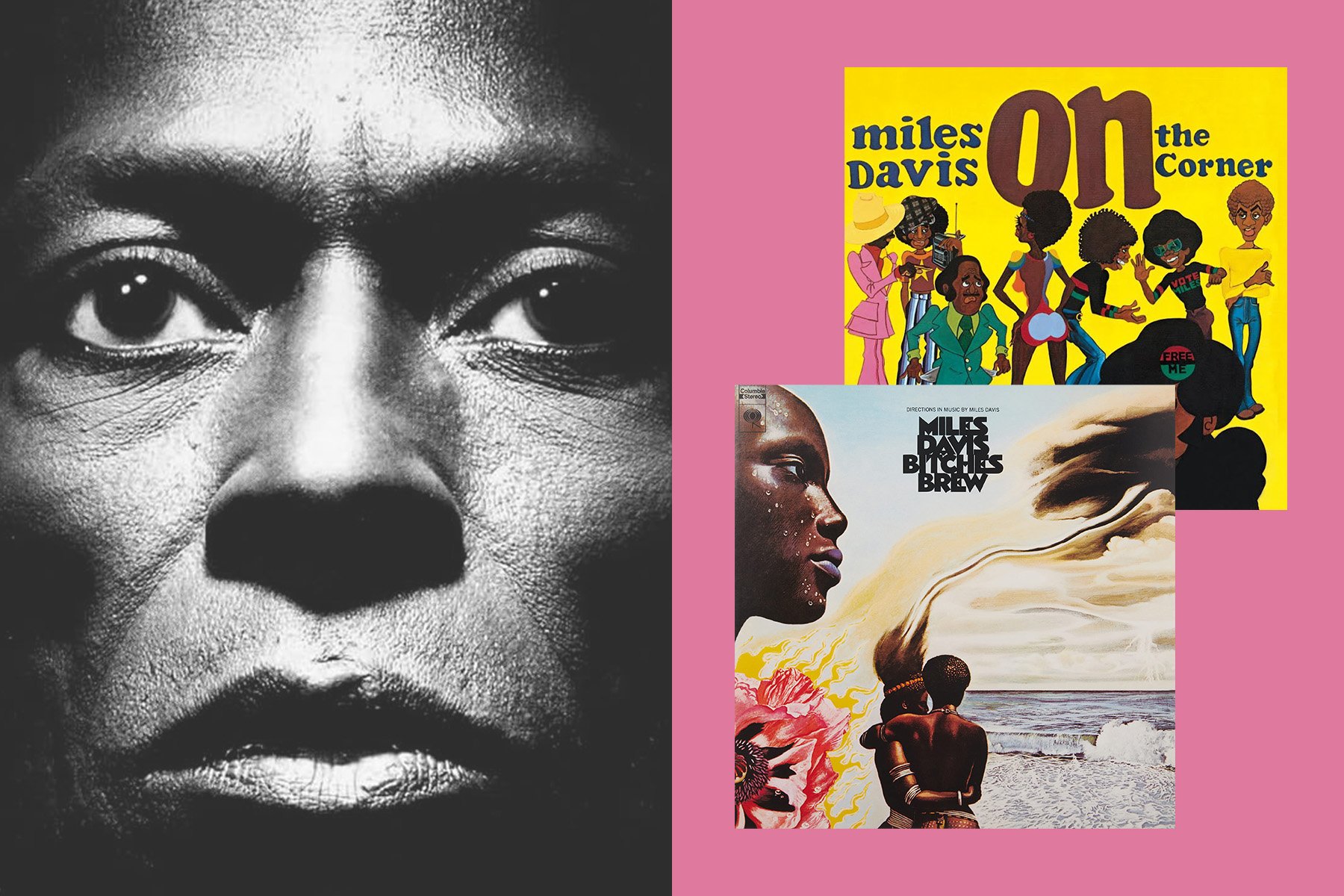

The very existence of the 200 Series Electric Music Box in some way suggests a fundamental difference in Bob Moog and Don Buchla's personal priorities. By the end of the 1960s, Moog's company was reaching significant commercial success; he employed a number of production builders to keep up with orders and engineers to help realize new instruments. Bob himself was at the helm for a while, up until the early 1970s, when the company was sold. After this, he remained on staff as an engineer until the late 1970s, working alongside other engineers to create new instruments. For the most part, these instruments repackaged his ideas in streamlined, simplified, more digestible forms...mostly in the form of self-contained keyboard instruments, and eventually, polyphonic keyboards—in some ways making the synthesizer even more like the piano or organ that preceded it. Moog's new instruments discarded the complexities of patching and extensibility of the modular infrastructure in favor of making something entirely self-contained that would be instantly playable and approachable by musicians. And in fact, the synthesizer industry on the whole seems to have been unconcerned with deeper exploration of the possibilities offered by modular instrument designs, instead turning their focus toward making simpler, more immediate, more compact, and more affordable instruments.

Not dissimilarly to Moog's sale of his own company, Buchla sold the 100 Series designs to CBS in the late 1960s, and created a small number of a few new designs while under their employ. But rather than continuing on to repackage and simplify his existing inventions into something more palatable for consumers, he developed the 200 Series: a considerably more complex instrument ecosystem which took many of the ideas from the 100 Series and deepened them significantly. This is where the core concepts of what most call "West Coast synthesis" were born.

1971 sales literature for the 200 Series Electric Music Box characterizes its strengths as such:

"THE ELECTRIC MUSIC BOX, Series 200, is a comprehensive collection of precision electronic modules for generating and processing sound. It is a system designed for those who desire simultaneous control of many aspects of sound and who demand professional standards of performance and reliability. The system features unusually high functional density, extended dynamic range, self-contained monitoring (preview) facilities, and unrestrained expandability. Interesting new techniques for polyphonic signal generation, dynamic spectral and timbral modification, complex pattern generation, and control of spatial location and movement are introduced. Organization is optimized for compactness, ease of access, and ready comprehension."

This is where I think it's important to consider that Buchla himself was a musician who used his own instruments. Because of that, he was able to use his own musical intuition to learn what did and didn't work about the 100 Series on a personal level, and to use those insights to envision a new way forward. He no doubt also took the advice of friends and colleagues—colleagues whose musical ideals were closely aligned with his own experimental tendencies—but I can't help but assume that a large part of what made each generation of Buchla instrument so much more rich and peculiar than those before it was simply that Buchla's own artistic intuition evolved along with the unforeseeable musical possibilities that each device presented.

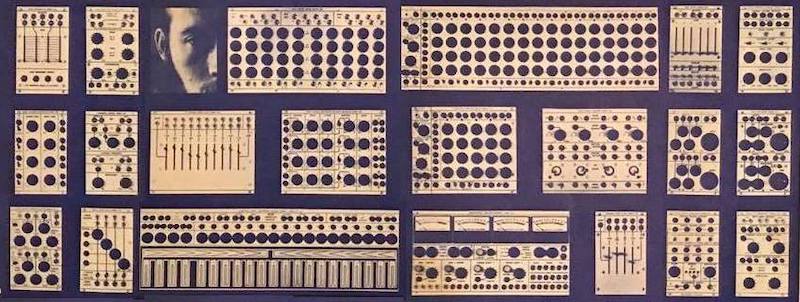

And in many ways, this is an apt explanation of what changed between the 100 and 200 Series. In the 200 system, unlike the 100, nearly every interesting parameter had a CV input—even parameters which, from a modern perspective might seem strange. For instance, you could voltage-control the sequencers' currently active stages. You could voltage-control an envelope's duration; you could even voltage-control the addressing of multiple otherwise independent sound sources. In some ways, the early 200 Series designs seem as if Buchla and his colleagues looked at the 100 Series and thought "What if we put a knob on every potential parameter? And what if we gave each parameter a control voltage input? And what if we build CV scaling tools into as many modules as possible?" The thing is, while most manufacturers were going the Moog avenue of scaling back and simplifing their modular systems into compact, portable instruments, Buchla was instead focusing not just on building an entirely new modular system, but on building something even more complex than before.

In the name of actually finishing this article some day, I can't use this space to give you a run-down of what every single Buchla 200 module did. But ultimately, the point I want to make is that, for many, the 200 Series is where Buchla hit his stride: providing an instrument that, at the time, was technologically unsurpassed, and made highly unique, idiosyncratic sounds that nothing else really came near. Moreover, the Buchla ecosystem allowed for an extreme level of detail for programming musical structure in a way not possible on contemporary Moog or ARP systems. Its voltage-addressable sequencers, polyphonic voltage distribution facilities, and its embrace of complex forms of randomness meant that the Buchla 200 system didn't just have a sound: it had an entire compositional philosophy baked into it. This philosophy privileged the concept of experimental, rule-based compositional structures, an embrace of chance, and the influence of human interaction at a level that didn't require a performer to play every single note. Instead, the performer/composer could guide evolving processes on a formal level, opening the door to quite unique methods of performance.

200 Series Audio Path and the Cornerstones of West Coast Synthesis

Development on 200 Series modules continued throughout the 1970s, ultimately giving us many of what people now describe as the "cornerstones of West Coast synthesis." What are these cornerstones of West Coast synthesis, you ask? To name a few: complex oscillators with integrated waveshaping, dynamic depth FM, lowpass gates, two-stage looping envelope generators, touchplate keyboards, and complex forms of randomness and sequencing. If it hasn't become clear to you by now, I'm going to just say it outright—I do take issue with this definition, and by proxy, with the term "West Coast synthesis" altogether. But before getting into my qualms, let's take some space to talk about the above characterizations—because there's a lot of useful and just plain fun stuff to unpack there.

Let's talk first about complex oscillators. Complex oscillators are now often defined as dual oscillator modules which contain internal continuous waveshaping functionality (usually using a wavefolder), and some means of inter-connection between the two oscillators, usually allowing a "modulation" oscillator to modify the "primary" oscillator's pitch, loudness, timbre, etc. In some ways, these ideas can be traced back to the Buchla 100 Series, where dual-oscillator modules were often employed to create complex sonorities by modulating one another's frequency or amplitude. Similarly, the 100 Series contained a couple of experimental/prototype modules for creating complex waveshapes/harmonic spectra through methods other than wavefolding (as with the 132 Waveform Synthesizer and 148 Harmonic Generator).

The first 200 Series oscillator was the 258 Dual Oscillator, used throughout much early 200 Series music by Morton Subotnick, Barry Schrader, and others. While this well may be the oscillator used in most famous early 200 Series compositions, it isn't the most strongly representative of the modern-day "complex oscillator" concept, as it doesn't have any internal modulation routing, nor does it have a wavefolder or terribly complex waveshaping functionality. The 258, of course, has recently been reissued by Buchla as part of their revisited 200 Series modules, and Tiptop Audio + Buchla have collaboratively introduced the 258t Dual Oscillator, a faithful adaptation of the 258 in Eurorack format (which is pretty awesome).

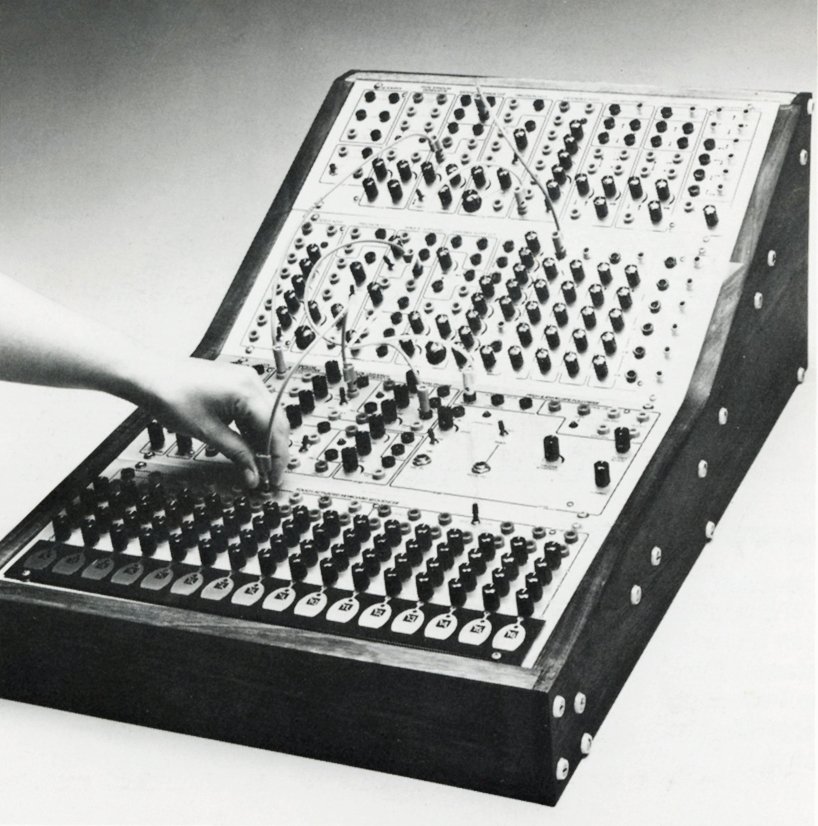

A 1970s Buchla Music Easel

A 1970s Buchla Music Easel

The first "complex oscillator" as we know it was found in the 1973 Music Easel: a compact (and now quite iconic) 200 Series system comprised of the 208 Stored Program Sound Source and 218 Touch Activated Voltage Source in a suitcase enclosure. The 208 had two oscillators: a Modulation Oscillator and a Complex Oscillator with a "Timbre" waveshaper (the first commercially-available implementation of a wavefolder in a musical instrument?) and optional crossfading between pre-set waveshapes. The Modulation Oscillator could impact the Complex Oscillator's pitch or amplitude via internal signal routings, and by using the Mod Oscillator's CV output, you could affect any other voltage-controllable parameter in the instrument.

It's worth mentioning that, in many ways, the Music Easel does seem to encapsulate basically all of the ideas we're discussing in this part of the article: it's often conceptualized as being the "West Coast Minimoog," like an all-in-one best-of-Buchla instrument. It has a five-step sequencer, peculiar envelopes, random voltages, an envelope follower, dual/complex oscillator, lowpass gates, touchplate keyboard—even in 2022, it's a seriously fun, well-considered design. Presently, Buchla USA sells the Easel Command, a modern update to the 208, and promises to open orders for their new version of the full Music Easel this year.

In roughly 1977 (several years into the 200's existence), Buchla introduced the 259 Programmable Complex Waveform Generator: the conceptual model for what most would now call a "complex oscillator." The 259 is a dual oscillator module with internal waveshaping and plenty of internal modulation routings. Both the 208/Music Easel and the 259 offered a CV input for controlling modulation depth—allowing for "dynamic depth FM" effects that many consider foundational to the "West Coast" sound. The 259 is the inspiration for modern designs such as Make Noise's DPO Dual Prismatic Oscillator (perhaps the first Eurorack module modeled specifically after the 259), Verbos's Complex Oscillator, the Frap Tools Brenso, Instruo Cs-L...the list goes on. Moreover, wavefolders are finding their way into standalone instruments from Majella, Arturia, and others—so all in all, it seems fair to say that the 259 has been the source of inspiration for many a current-day synthesizer designer. But, as stated, the "complex oscillator" as we know it wasn't the only Buchla sound source, by any means.

In place of conventional VCAs (voltage controllable amplifiers), the 200 Series also introduced Low Pass Gates (present both in both the 292 Quad Lopass Gate, 212 Dodecamodule, and in the 208/Music Easel): a peculiar circuit that couples filtering and audio amplitude scaling to create an inherently linked response between a sound's loudness and brightness. Given the conceptual similarity between this parametric coupling and the response of acoustic instruments (which tend to become brighter/richer in harmonics the more loudly they are played), many describe the Low Pass Gate as having a very "natural" or "acoustic" sound. Additionally, Buchla Low Pass Gates utilize vactrols in their control path, making for a somewhat sluggish, non-immediate, and fairly nonlinear CV response—creating ringing tails when controlled with percussive envelope shapes, and a gradual "buildup" of brightness/loudness when "pinged" with rapid successions of triggers or short envelopes. This peculiar circuit is certainly responsible for much of "the Buchla sound," and has spawned, yet again, a significant number of modern-day Eurorack module spinoffs, from Plan B's long-discontinued Dual Timbral Gate to the present-day Make Noise Optomix, Erica Synths Black LPG, Doepfer A-101-2, and plenty of others.

Many prevailing definitions of West Coast synthesis reduce down to simply the presence of complex oscillators and lowpass gates. Of course, the Buchla 200 Series featured a wealth of other audio processors, from variable-bandwidth filters to frequency shifters, spring reverbs, balanced modulators, dynamic filter banks, quadraphonic audio processors, and more. The audio side of things, though, is only one part of the equation. Digging more deeply, we can start to analyze the control structures at place in the Buchla ecosystem, which will take us a step closer to the more interesting core of Buchla's work.

200 Series Control Structures and the Cornerstones of West Coast Synthesis

As stated above, the 200 Series contained a wealth of controllers and complex CV sources, from touchplate keyboards to highly-programmable envelopes and sequencers—often so complex and general-purpose that simply calling them an "envelope" or a "sequencer" seems quite reductive. As you'll recall from our previous discussion about the differences between East Coast and West Coast synthesis, the approach to control and interaction is one of the most significant divergences in approach between Buchla and Moog's designs...so let's dive in.

Many often say that Buchla's instruments all feature two-stage envelope generators—an oddity to those used to "standard" four-stage ADSR envelopes. For instance, two-stage envelope generators could be found in the 280 Quad Envelope Generator, 212 Dodecamodule, and 281 Quad Function Generator. However, thinking of these as strictly "Attack/Decay" envelopes is a bit reductive: with some thought, it's quite possible on both 100 Series and 200 Series envelope modules to program delay, hold, and sustain stages; and moreover, the 200 Series envelopes could be made to self-cycle through the use of their own trigger outputs (or dedicated mode switches on the 281). The takeaway here shouldn't be that "Buchla uses two-stage envelopes"; the takeaway should be that Buchla created tremendously flexible envelopes which could be programmed (via patching) to create a vast range of shapes and responses to incoming pulses. Look to the ubiquitous Maths by Make Noise and Tiptop's reissue of the Buchla 281 for clear influence.

Close-up of the Buchla 217, from the 1971 200 Series product catalog

Close-up of the Buchla 217, from the 1971 200 Series product catalog

The 200 Series did also further develop Buchla's use of capacitive touchplate-based keyboard modules—both with arbitrarily tunable outputs (as in the 216 and 217) and with chromatically-organized, pseudo-black-and-white-keyboard arrangements (as in the 218, 219, and 221). But, as with Moog's mechanical keyboard, these were only one way of interfacing with the instrument. The 200 Series also featured polyphonic mechanical keyboards in the form of the 237 and 238, envelope followers in multiple modules, and more. My point here is that the takeaway shouldn't be that Buchla systems were played with touch keyboards: the takeaway should be that Buchla systems provided a vast range of potential control methods, in order to provide as open-ended an approach as a performer could need, hopefully providing the tools required to execute any given control-related musical need. Modern responses to this corner of Buchla's instrument design are vast, from the Make Noise 0-CTRL and Verbos Mini Horse to the Soundmachines LP1 Lightplane and more.

Likewise, Buchla's systems did incorporate quite complex forms of randomness. The 200 Series featured both the 265 Source of Uncertainty and 266 Source of Uncertainty: each stochastic voltage generators that allowed the user to determine specific rules or conditions by which randomness could be applied to different parts of their patch, as well as the timing, intensity, and degree of randomness. Unlike what many might say, this doesn't necessarily mean that Buchla systems are all about making random sounds—but they do privilege the use of highly controlled randomness in order to take patches into unexpected directions, to create generative structures with variably-predictable outcomes, and even to surprise the person programming them. Modern response to this corner of Buchla's instrument design include the Verbos Random Sampling, Frap Tools Sapèl, and many, many more. And yes, of course, as with other modules, Tiptop Audio have also directly cloned the 266 and adapted it for use in Eurorack format as the 266t, about which you can read more here.

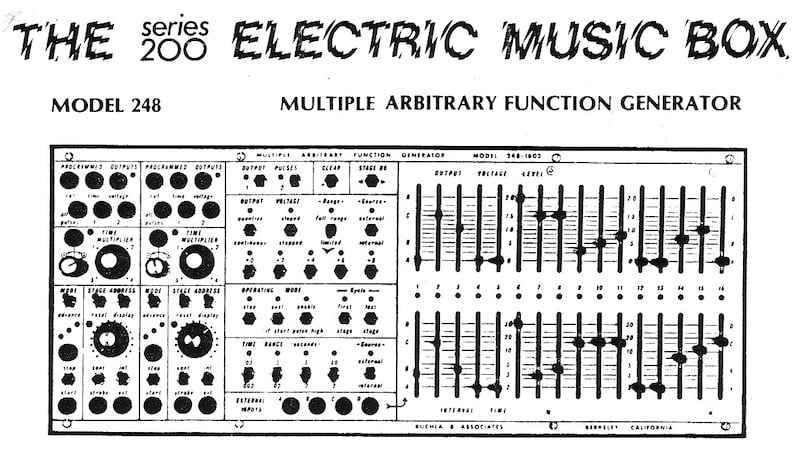

Likewise, Buchla's systems did incorporate quite complex sequencing options as well—sources of "predictable" outcomes which were every bit as complex as the systems' respective sources of unpredictable outcomes. These range from the seemingly-simple 245 and 246 Sequential Voltage Sources to the profoundly complex MARF/Multiple Arbitrary Function Generator (which...in many ways is much more than just a simple sequencer). But, as with all of the things I've listed above, I don't think the takeaway should be that "Buchla systems are all about using sequencers." Instead, I think a more useful takeaway is that Buchla systems aimed to offer whatever balance of predictability and unpredictability you could possibly need, often by taking otherwise simple synthesis concepts and pushing them to the point that they could achieve much more than you might expect them to do, disrupting their "linearity" in such a way that an artist really needs to sit down at the instrument and decide how much control and how direct a form of control they want over the sound—with everything from "strict repeatability" to "outright unpredictable chaos" being equally valid options. The aforementioned Make Noise 0-CTRL, Verbos Voltage Multistage, and the (now-discontinued) Mutable Instruments Stages all take direct inspiration from this part of Buchla's system design.

I could go on listing everything a Buchla 200 system was capable of doing—but I'm hoping that as you read through the above list, you notice that, generally speaking, I don't really think that complex oscillators (in the prevailing sense) and lowpass gates, for instance, are the most interesting aspects of Buchla's instrument design. Consequently, these being some of the most obvious and concrete examples of what people use to distinguish between the East Coast and West Coast approaches to synthesis, I have to feel like perhaps the East/West Coast distinction altogether is less helpful than it initially might seem. I do think that there is a lot to learn from both Buchla's approach and from the lineage of Moog's instrument—and I do think that, despite their many similarities, they actually are very different, and that these differences are very worth exploring.

That in mind, let's approach the end of this particular article by going back to the source. Where did the terms East Coast and West Coast come from, anyway? And what did Buchla himself feel were the most important aspects of his approach to instrument design?

East Coast vs. West Coast Synthesis: Origins of the Terminology

The precise origin of the terms "East Coast" and "West Coast" as applies to synthesizer design is...unknown, at least to me. This section of the article contains some unsubstantiated speculation as well as some outright facts; I'll try to distinguish between these as we go. I will say before continuing: if you have any evidence worth considering about the origins of these terms, I would be quite happy to talk. Please reach out if you have any insight worth consideration. I'm happy to update this article if any relevant info comes down the pipeline.

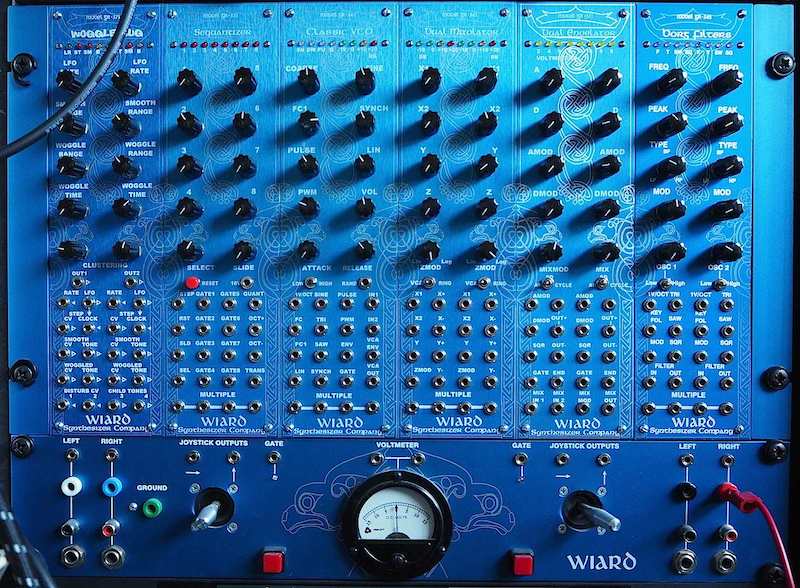

A Wiard 300 System—image via SphereMusic

A Wiard 300 System—image via SphereMusic

First of all, I'd like to address that I've heard at many points in the last few years that the East/West coast distinction as pertains to synth design is a completely new idea that came along with the advent of Eurorack. Well, this "coast" concept certainly did become considerably more widespread as Eurorack became popular. I believe that one factor in this terminology's proliferation had to do, strangely enough, with some posts in 2006 from Grant Richter on the Yahoo mailing list for his company Wiard. Richter designed synthesizers that borrowed and adapted many concepts from Buchla's designs (Richter being owner of a quite rare Buchla system, himself). In describing his own design philosophy, he published a definition of both East and West Coast synthesis which largely aligns with the current prevailing definition—and as I recall, around 2007 and the ensuing years, this information was shared in online forums fairly often. As such, this idea was close in mind when the forthcoming wave of Buchla-inspired modules (from Plan B, Make Noise, and others) required marketing language which could succinctly explain their ethos in a world where Buchla's designs were still quite obscure. (See this ModWiggler post for a publicly-visible archive of some of Richter's discussions on the topic.)

But Grant Richter certainly wasn't the first to use these terms in this way; frankly, it's a bit unclear where they originated, and how they first became associated with synthesizers. I do have some theories, however. During my own musical upbringing, I was taught about midcentury trends in American academic and experimental music composition, many of which were characterized as belonging to an "East Coast" school of thought or a "West Coast" school of thought. Generally, composers/compositions characterized as "East Coast" were based in East Coast universities, and took a more rigid, stark, modernist approach concerned with formalism and experimental organization of otherwise traditional musical parameters. Serialism, for instance, was a common tool of "East Coast" approaches to composition (as in the work of Milton Babbitt, Charles Wuorinen, etc.), as was free atonality arranged around the conventional 12-tone scale (as in Elliott Carter or Leon Kirchner's music). "West Coast" composers/compositions, though, favored a more open-ended/conceptual/free approach, in which the materials of music altogether were brought into question. Often, "West Coast" compositions valued new means of musical organization, which might originate from analysis of non-Western musical tradition (as in the work of Lou Harrison), creation of new instruments/tuning systems (as in the work of Harry Partch), reliance on chance (as in the work of John Cage), and more.

Regrettably, while researching for this article, I have failed to find any definitive source that uses this terminology to describe these differences in compositional concept—this was simply something I was taught in college classrooms through word-of-mouth. (I have since seen the East Coast/West Coast distinction applied to approaches to musical and artistic minimalism, which is certainly related, but doesn't quite encompass the entirety of what I'm describing here.) But regardless whether this idea can be pinned down with supporting published text or not, the fact that I was indeed taught this by composers who themselves were taught by composers at the center of this "coastal" stylistic distinction makes me suspect that this idea bears repeating, and is perhaps related to the topic of synthesis. After all, it's worth considering that, at the time of their introduction, academic institutions were one of the primary clientèle for modular synth manufacturers: schools were some of the only institutions which could afford these instruments, and some of the only institutions willing to concede that experimental musical technologies well might be worth the associated expense. It wouldn't surprise me if terminology surrounding academic/experimental music found itself attached to these instruments, especially given that, indeed, the general approach of each of these instruments does seem relatively aligned with the purported musical ideals of each of these otherwise-unrelated "coastal" schools of music composition.

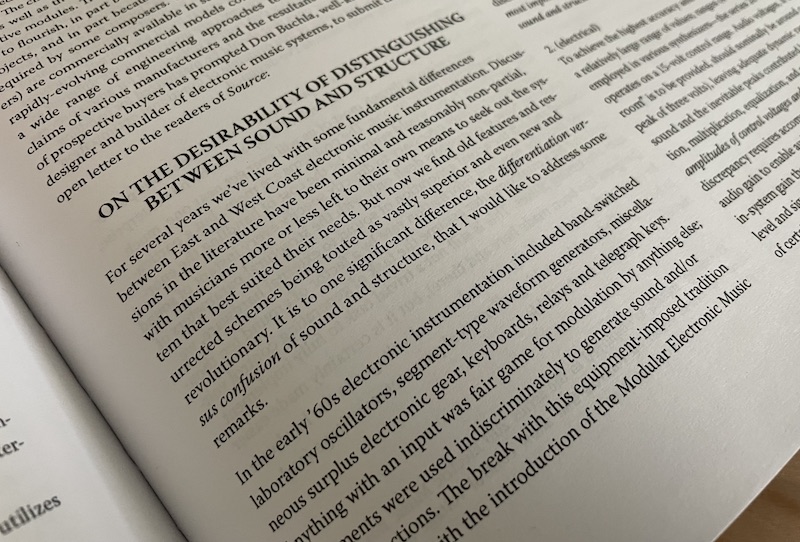

Excerpt from UC Press's collection/republication of Source magazine

Excerpt from UC Press's collection/republication of Source magazine

Regardless, there is still evidence of the "East Coast vs. West Coast" distinction being used specifically in the context of synthesizer design well before Richter's use in 2006. The earliest mention I have found in writing comes from 1971's ninth issue of Source magazine, a short-lived publication dedicated to experimental music. All issues of Source were re-published as a collection by UC Press in 2011. This particular issue notably features a short letter written by Don Buchla himself, titled "On the Desirability of Distinguishing Between Sound and Structure." The letter opens:

"For several years we've lived with some fundamental differences between East and West Coast electronic music instrumentation. Discussions in the literature have been minimal and reasonably non-partial, with musicians more or less left to their own means to seek out the system that best suited their needs. But now we find old features and resurrected schemes being touted as vastly superior and even new and revolutionary. It is to one significant difference, the differentiation versus confusion of sound and structure, that I would like to address some remarks."

Buchla goes on to describe several points justifying his instruments' distinction between audio and control signals (which, as stated in our previous article, used completely different cable types and voltage ranges). Buchla states that, whereas Moog's system featured 1/4" phone cables for the vast majority of signal connections, his system was superior for visual parsing of complex patches, for establishing adequate dynamic range/headroom for audio signals and control voltages (which have differing functional requirements for headroom), for optimizing modules to account for the logical differences between the function of CV generators and audio generators as pertains to signal mixing, etc., and for the eventual inclusion of computers as part of the synthesizer, which, at the time, were not generally capable of creating audio-rate information but could produce data quickly enough for satisfactory use as a control voltage source. A similar, more detailed account can be found in "The Horizons of Instrument Design: A Conversation with Don Buchla," an article/interview published in Keyboard Magazine in December 1982, after Buchla had put many more years of thought into his approach to instrument design. (A transcription and scan of this article can be found in this ModWiggler thread.)

But perhaps the most interesting published statement I have found related to the "East vs. West Coast" distinction came from yet another interview with Don Buchla himself, published in the August 1983 issue of PAiA's Polyphony magazine.

After the 200 Series: the Evolution of Language

Titled simply "An Interview with Donald Buchla," John K. Diliberto's article in Polyphony begins by characterizing Buchla as a "classic American loner—a living realization of the all-too-mythical individualist who follows his particular vision despite all the obstacles, hardships, derision, and easy exits that are available to him." In this article, they deeply discuss Don Buchla's ideas about the unique possibilities of electronic instrument design, discussing abstractly the past/present/future of electronic instruments and Buchla himself. Before going on, let's talk about what happened between the introduction of the 200 Series and 1983, the point at which this article was published.

At this point in time, Buchla had largely moved on from designing modular instruments, as had most other makers in the synthesizer sphere, in favor of self-contained but reasonably extensible instruments. Buchla had already experimented considerably with the possibilities of computer control in synthesis, and had produced several unique devices that each took different approaches to the integration of computers into synthesizer design. Let's take a quick look at some of these before returning to the article in question.

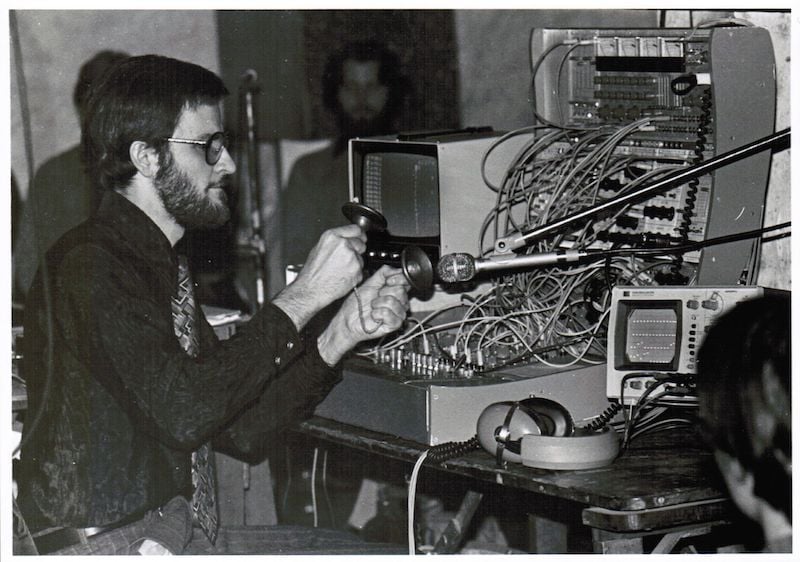

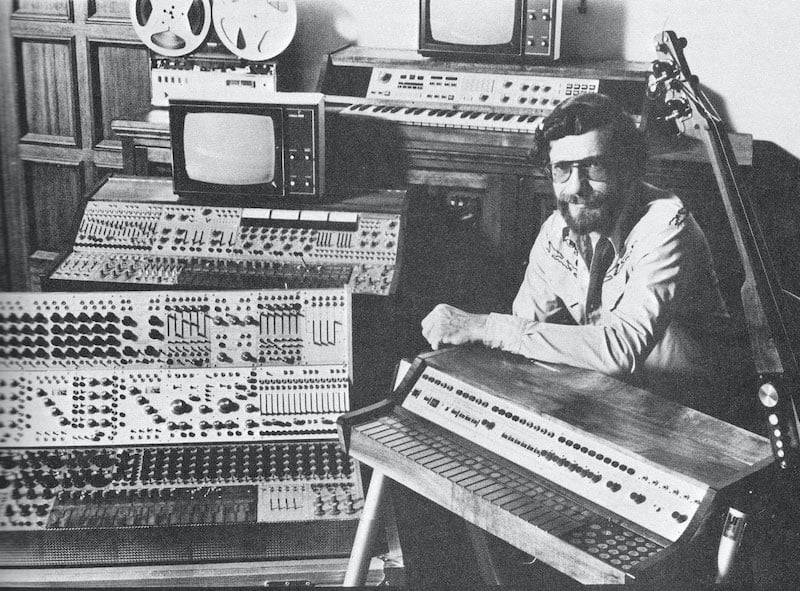

From roughly 1969 to 1975 (contemporaneously with work on the 200 Series), Buchla worked with D.N. "Lynx" Crowe to develop the experimental 500 Series, a computer-controlled hybrid instrument concept which ultimately yielded very few complete instruments (none of which remain intact to this day). The 500 Series's concepts were refined with the late-1970s 300 Series, an instrument that paired 200 Series modules/housings with a specialized computer and programming language (called PATCH). The 300 aimed to do most of the system's "heavy lifting" for control voltage generation from the computer itself rather than from dedicated sequencer modules, complex envelope modules (like the aforementioned Model 248 MARF), etc. Sequence tables and voltage functions defined completely in the computer functionally replaced some modules that might otherwise seem "foundational" to so-called West Coast synthesis. The computer was programmed via the 221 Kinesthetic Input Port, a touchplate keyboard module similar to the original Easel's 218, but specifically designed to help program/perform with the 300 Series computer. (The images in the above carousel, in order, are the Buchla 502, David Rosenboom performing with a 300 Series system, and "sequence definition" details from the 300 Series/PATCH-IV manual.)

Don Buchla and experimental composer David Rosenboom then collaborated to produce the 1980 Touché (pictured below), a significant departure in form from Buchla's prior, more modular designs. The Touché was a self-contained device which paired specialized hybrid digital/analog sound generation hardware with a completely new instrument programming language, FOIL (the Far Out Instrument Language, designed by Rosenboom).

Often seen paired with a CRT monitor, the Touché integrated all soundmaking hardware and control programming into a single housing, foregoing "modularity" of the audio path altogether in favor of a fixed audio scheme. Moreover, there were no more two-stage envelopes or 200-esque sequencers—instead, the Touché featured multi-segment "time varying functions" programmed from the computer interface. There were no "complex oscillators," per se—each voice featured three oscillators (one for sound generation, two for modulation of pitch and timbre, respectively), and a waveshaping scheme based on selectable digital transfer functions rather than analog wavefolders. And of course, the instrument was primarily played via black-and-white mechanical keyboard—albeit one that could interact with complex algorithmically-defined internal control structures. It featured the ability to store and recall Instrument Definitions: complex arrangements of all parameters associated with the sound engine. While it did still employ low pass gates, the Touché was already a significant departure from what many think of as "typical" Buchla designs.

Then, c. 1982, Buchla introduced the 400 Series, which in many ways took the groundwork of the Touché and went even further. Like the Touché, the 400 was a self-contained instrument with a fixed audio signal path. (A 400 is pictured below—image via Google Arts and Culture, originally sourced from the Canadian National Music Centre. Subsequent images are sourced from the 1982 Buchla 400 user manual.)

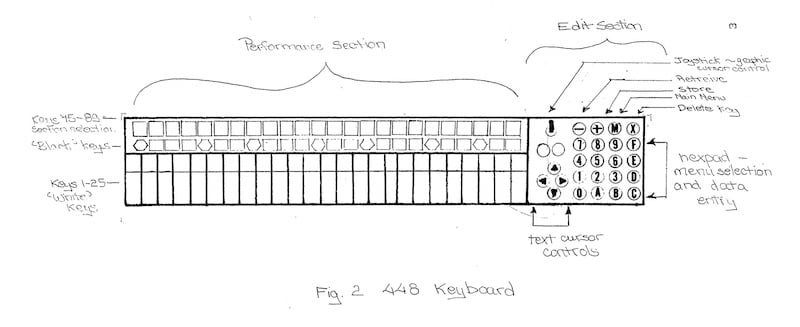

The 400 featured six voices with two oscillators per voice (one for sound generation, one for modulation), waveshapers based on user-definable digital transfer functions, and resonant lowpass filters(!). The instrument could be played polyphonically from a touchplate keyboard (or a mechanical keyboard on the model 406), and each of its six voices could use entirely separate instrument definitions (for up to six-part multitimbral behavior). The internal computer handled all control generation via multiple available instrument programming languages—and the MIDAS (Musical Instrument Definition and Scoring) language included a graphical score editor for independent, but highly-predictable control of each individual voice. The keyboard was highly reprogrammable, and could perform any number of internal functions (as could the keyboards on the prior 500, 300, and Touché). Later, the 700 Series continued these concepts, but featured a significantly altered sound generation scheme based on multi-operator, almost Yamaha DX-like FM synthesis. Buchla then went on to develop elaborate MIDI controllers with internal algorithmic data conditioning (the Thunder, Lightning, and Marimba Lumina), and the the 21st century 200e Series (still in production) borrows concepts from the 200 Series and pairs them with ideals first seen in Buchla's self-contained hybrid instruments.

My point here is that what we think of as "West Coast" synthesis is a small fraction of what Buchla accomplished in his lifetime; but even by the early 1980s with the 400 Series, it was clear that he already considered the developments of the first 20 years of synthesizer design to be significantly outdated. Returning to his interview in Polyphony, Buchla characterizes the differences between his early instruments and Moog's by saying that "his [Moog's] instruments have been more oriented to traditional concepts of musical structure and mine [Buchla's] towards non-traditional concepts. At one time we were considered to be West coast versus East coast and in some sense there is truth to that concept. Certainly ten or twenty years ago more experimentation took place on the West coast than the East coast."

In his quote, from the early 1980s, Buchla already refers to the East/West distinction as being outdated. Going on to describe the changes in the field of electronic music instrument development since he and Moog created their first modular instruments, Buchla had this to say:

"A lot of learning has gone down in twenty years. We've found that certain kinds of structural interactions can be assumed. Certain others can be taken over by the computer that controls the innards of our instruments, and can be specified in a way that can make changes in patches instantaneous rather than tedious. The computer has made a lot of changes but it's only a small part of it. The language is the major part of it. The operative language behind our instrument has taken over a lot of the role of establishing the relationship between input gesture and instrumental response . . . I like to regard an instrument as consisting of three major parts: an input structure that we contact physically, an output structure that generates the sound, and a connection between the two. The electronic family of instruments offers us the limitation, if we approach it traditionally, and the freedom if we approach it in a new way, of total independence between input and output. And in fact the necessity of some way of generating a connection between the two . . . The relationship between input and output is fixed with traditional instruments; it's totally flexible with electronic instruments. It was established by the setting of knobs and routing of the patch cords in the electronic instrument of the 60s. But in the electronic instruments of the 80s it is established by human intelligence working through sophisticated electronics. Therein lies the exciting possibilities of electronic instruments: the instantaneous remapping of the relationship between input gesture and output response. We've only begun to investigate this because of our own ignorance and our dedication to tradition . . ."

In this interview, Buchla in one fell swoop says not only that the West Coast and East Coast distinction is outmoded, but that the (necessary) experimentation that came along with modular synthesis, after years of experience, had revealed what parts of an electronic instrument's structure could be reasonably pre-established (the sound generation path), and what parts were more ripe for further exciting experimentation: the language, the logical connection between an instrument's playing interface and the sonic outcome. If anything, I see this as being more closely aligned with Don Buchla's legacy, and a more solid thread that weaves through all of the devices he developed: they're all about questioning the nature of the compositional approach, and about using electronic processes to obfuscate, abstract, or otherwise augment the nature of the physical relationship a performer-composer has with their instrument.

As we've seen, Don Buchla for many years stopped making instruments with "complex oscillators," lowpass gates, sequencers, and modular structure altogether: but he never stopped making instruments that forced you to question your own musical assumptions. If for that reason alone, I find the "coastal metaphor" to be quite limiting: it reduces multiple brilliant people's life work into something considerably less nuanced and interesting than it actually was by focusing on a period in time in which they were really just getting started. In the end—to me—wavefolders are much less interesting than the mysterious, ever-evolving relationship between humans and machines.

Deconstructing the Metaphor

There are plenty of other reasons to be somewhat skeptical of the coastal metaphor. For one, it feels like a form of subtle historical revisionism: while Moog and Buchla purportedly kept their eyes on one another in the early days of their instruments' development, they were not adversaries, and painting them as such isn't helpful in understanding how and why their instruments work the way that they do, or the music that was created with them.

As stated above, I also find it unhelpfully reductive to boil down Moog and Buchla's accomplishments into functional flowcharts of how specific instruments work. While I do love the way these instruments sound, and do find their individual components to have a distinct charm, I can't help but feel that there are much deeper ideas at work. It's not just about whether to use a resonant filter or not. For instance, I think that the differences between Moog's focus on instruments with stable timbres, played on a note-by-note basis versus Buchla's focus on instruments with ever-changing sound and abstracted relationship between input and output is a considerably more interesting idea than the typical East/West definition includes. Moreover, the "East vs. West" mentality ignores the not-insignificant amount of overlap between their approaches, and the truly fascinating history of how their instruments developed and diverged despite their initial common footing.

The full story of West Coast synthesis no doubt also should include an account of Serge Tcherepnin, the People's Synthesizer, and the Serge Modular Music System, which borrowed significant influence from Buchla's design approach and in many ways developed into even more peculiar, esoteric methods of control voltage generation. However, the Serge system also takes significant influence from developments on the Moog/"East Coast" end, and frankly, getting too deep into how the Serge works and sounds ultimately doesn't make the argument for the "coastal" distinction any stronger. If anything, it points out just how much these ideas cross-pollinated in the early years of synthesizer development. Heck, focusing on the East/West distinction also minimizes the contributions of countless others to the field altogether—and after all, so much has happened in the world of electronic instrument design in the last 60 years. In reality, it doesn't all center around two individuals.

Additionally, painting the West Coast and East Coast school as if they were ideologies competing with equal footing is quite misleading, if only because the historical presence/significance/influence of the "East Coast" side so significantly outweighs the presence/significance/influence of the "West Coast." When we talk about East Coast synthesis, we're not just talking about Moog—we're also talking about ARP, E-Mu, Roland, Korg, Sequential Circuits, Oberheim, and almost every other synthesizer manufacturer that has ever existed. In comparison, there just aren't that many original Buchla instruments out there; they were all produced in comparatively low quantities, and as such, few people ever get to see one in person, let alone play one. So, for those interested in the history of electronic instruments, Buchla carries with it a particularly interesting mythology about an ideologically-driven outsider/genius—but, as much as I love those instruments, any argument directly comparing their historical impact to that of Moog's must be taken with a grain of salt.

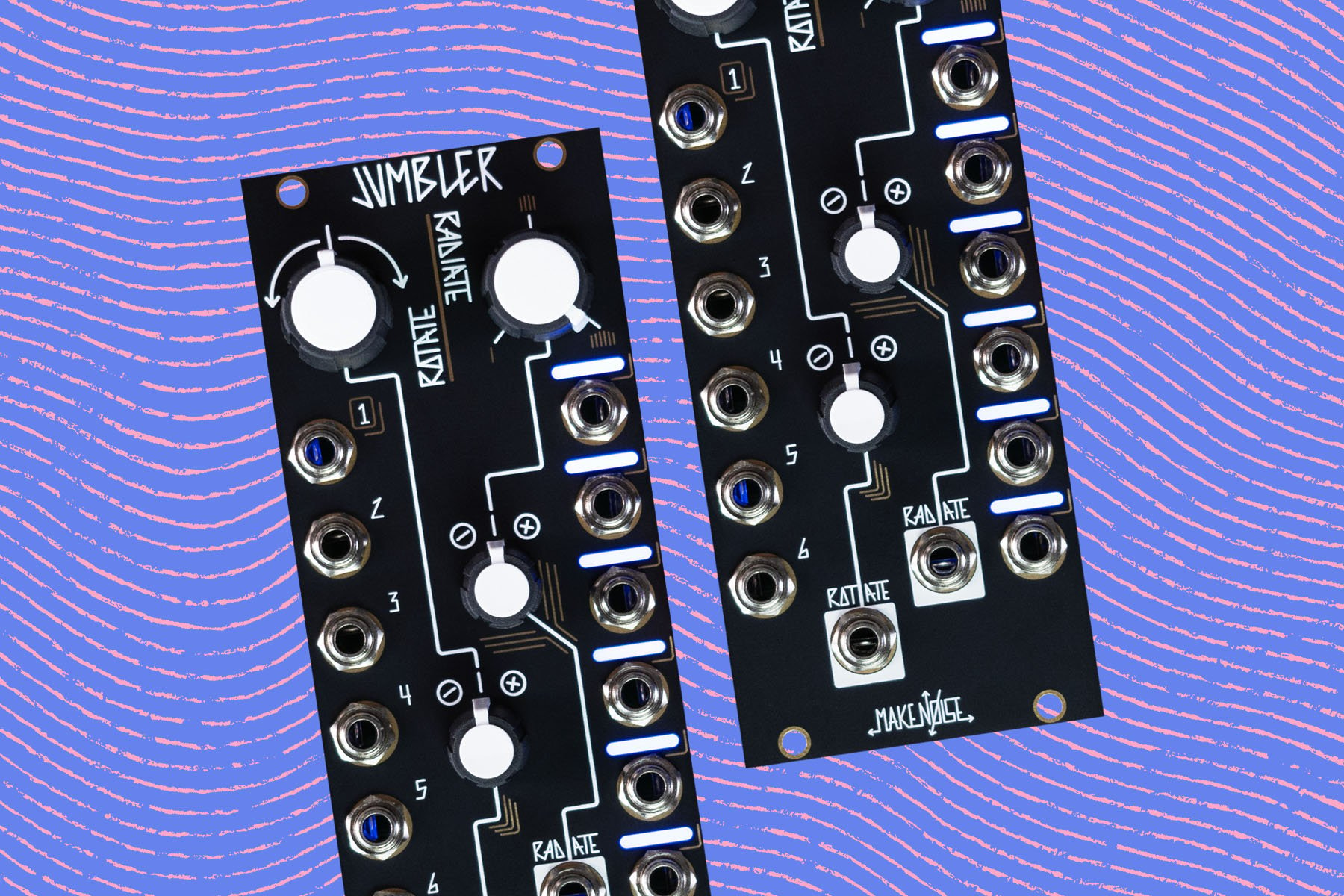

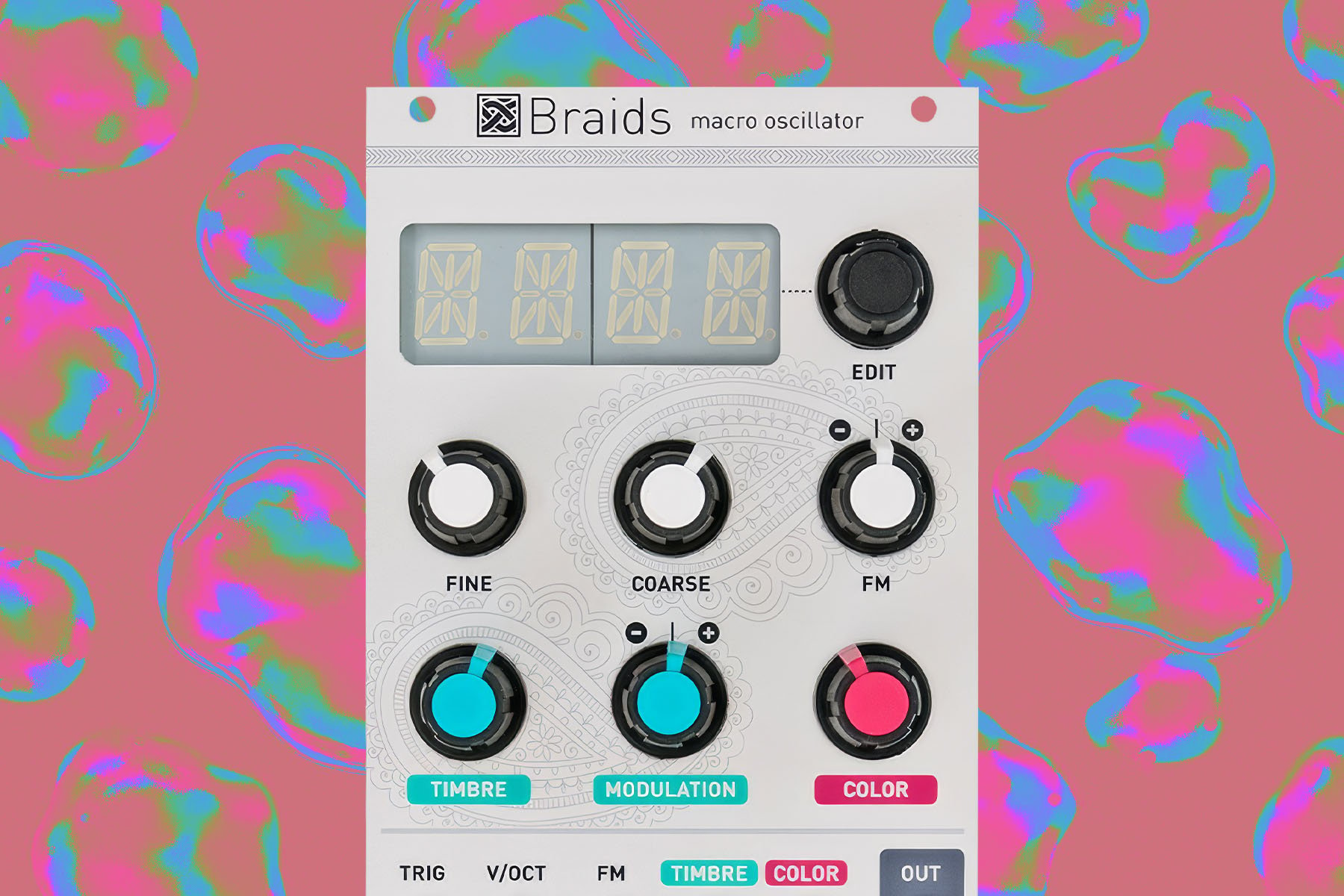

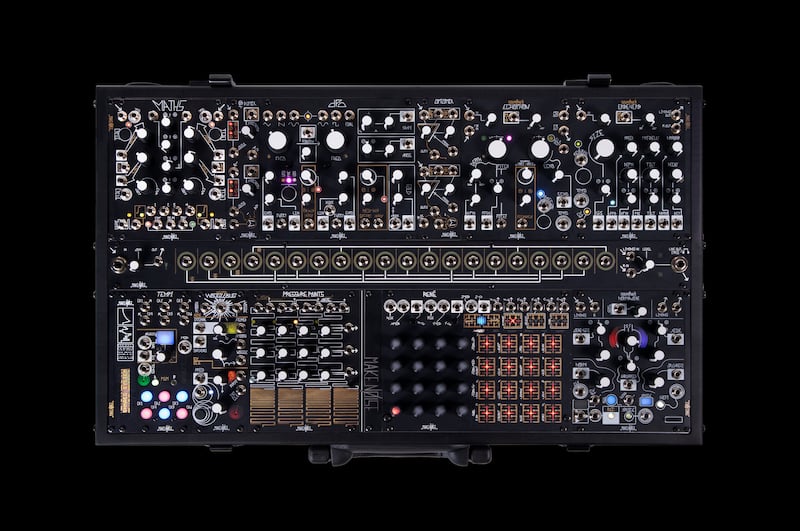

Or at least, that has been true up until the last decade or so. As discussed extensively in our recent article about the Tiptop + Buchla Eurorack 200 Series, Don Buchla's story and the legend of his instruments has become a tremendous source of inspiration for current-day instrument designers—and as such, it's much easier than ever before to experience Buchla-esque sounds and CV generation. Countless Eurorack manufacturers produce Buchla-inspired designs—many of which present the same embrace of nonlinearity, extreme ranges, and complex linkages between performer and sound. Make Noise (whose Shared System is pictured above), Verbos Electronics, Industrial Music Electronics, Frap Tools, and countless others explore many of these ideas with their own aesthetic angle and artistic twists, presenting aspects of the Buchla "magic" through the perspective of their equally creative, thoughtful, and forward-thinking designers.

Moreover, as stated above, Buchla USA continues to produce the Easel Command and the forthcoming new Music Easel, a design that since its 1973 introduction has presented a compact, concise, and quite complete way to experience not only "the Buchla sound," but the Buchla mindset as well. Furthermore, Buchla USA has also recently announced the reintroduction of the 200 Series in their original form factor, following the efforts of Roman Filippov (of Black Corporation) and others to reverse-engineer and reconstruct classic Buchla modules using currently-available parts and production methods. In the end, I am thrilled that we've circled around to paying so much attention to Buchla's accomplishments, and I think the musical world will wind up being more interesting because so many of his ideas are proliferating.

However, my perspective throughout this article remains. Yes, it's very possible to get your hands on an instrument with a wavefolder, or dynamic depth FM, or lowpass gates. Most likely, the term "West Coast synthesis" will continue to be used, and it will likely continue to popularly refer to the physical materials of the Buchla 200 Series and its influence on present designs. But, for me, that shouldn't be the takeaway when examining the story of how these instruments came to be: instead, I believe that the more important point worth considering is that there are no rules about how you should make music, and no rules about how an instrument can work, or what an instrument can be. And if someone tries to tell you otherwise, ignore them and continue to pursue whatever seems interesting and inspiring, teetering on the edge of possibility.