If you’re building a home recording setup and you're ready to start playing back and recording sounds, the time has come to consider getting your first audio interface. An audio interface serves as the hub between your microphones, instruments, computer, and speakers. Given the sheer number of options out there, though, choosing the best interface for your personal setup can be difficult. And of course, there's no one-size-fits-all solution: which interface is right for you depends on a number of factors, so making a decision relative to your personal needs is crucial.

In this article, we'll take a stab at defining what exactly an audio interface is, what they commonly contain, and how you can start to make an informed decision about the interface that best suits you.

So What Even is an Audio Interface?

An audio interface is a specialized computer peripheral designed to help you get sounds into and out of your computer for recording—like a standalone sound card that allows you to interface with your recording software of choice. So when you use an audio interface, you can forego your computer's built-in mic and speakers and instead connect to other gear—you could connect studio microphones, studio monitors, and even connect electronic instruments directly for the sake of recording. For an example of how a typical audio interface might be laid out, see below and read on.

Often, interfaces connect to a computer via USB, Thunderbolt, or other standard digital communication protocols. Additionally, you'll find that most interfaces have some number of audio inputs and audio outputs. Inputs allow you to receive audio from the external world—so you could plug in microphones, synths, guitar, or other devices and get their sound into your computer for recording, allowing for much cleaner, clearer recording that you could get out of your computer's built-in mic. Internally, the input connections are connected to Analog to Digital Converters (ADCs) that help translate the analog signals from your gear into a digital format that can travel over USB and be interpreted by your computer. In addition to ADCs, most interfaces also include Digital to Analog Converters (DACs) that translate the computer's digital audio output back into an analog format for sending to external devices. An interface's outputs might include speaker outputs so that you can listen to your mixes on studio monitors, or headphone outputs for more discreet listening. Many budget-friendly interfaces also include MIDI inputs and outputs, allowing you to communicate directly with MIDI-capable synths, drum machines, or other electronic music equipment.

So in so many words, an interface is meant to act as a hub for your recording setup—translating the analog signals from instruments and mics into a digital format your computer can understand, and then turning the computer's digital audio output into something you can monitor via speakers or headphones. Interfaces can be large or small, expensive or affordable—so now that we have a basic working definition of what an interface is, let's analyze some ways you might determine whether what specific interface is right for your needs.

The Ageless Question: Should I Get a Mixer or an Audio Interface?

We often see folks new to electronic music confused about the functional difference between a mixer and an interface, and why you might need one versus the other. This is complicated by the fact that many musicians use audio interfaces and mixers in tandem or as replacements for one another—and truthfully, mixers and interfaces can have a significant amount of functional overlap. Understanding these devices' relationships with one another can help to demystify some options for how to build your recording setup.

First things first—we need to offer advice regarding a common misconception about building your home studio setup: for many musicians building a home studio, a mixer is not necessary. It can offer some conveniences, but the image of a recording studio with a giant mixing console isn't necessarily what you need to model your workflow after. In most project studios, the traditional role of the mixing console is entirely handled by your audio interface and your recording software: the interface gets sound into your computer on individual tracks, and the mixing process happens entirely "in the box" in your Digital Audio Workstation (DAW) software of choice.

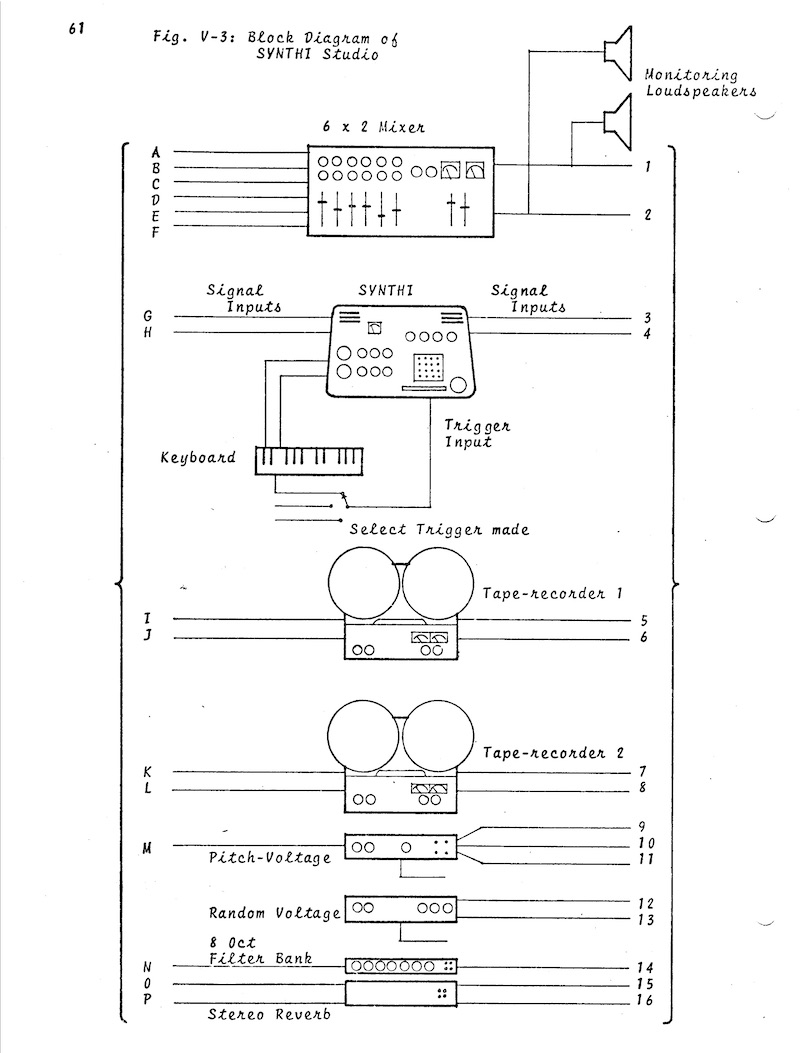

So if that's the case, why are mixers even a thing? Well, while high-end mixing consoles are praised for their sound quality and do play a role in professional studios, oftentimes mixers are simply intended for live use: they have several input channels, and function primarily as a way of combining multiple inputs into a single set of stereo outputs to go to a single destination, such as a live PA. Once mixed, the sounds are intrinsically linked together: they are part of a single combined signal, and cannot be separated from one another for further editing/processing. In analog studios, this is critical—you need to be able to combine all of your tracks to print on tape (which, unlike the computer, typically supports a very low number of independent audio channels), or to apply similar processing to multiple sounds simultaneously.

So in live situations or in analog studios, mixers are a key piece of the puzzle—audio often needs to be mixed together for one reason or another. But for the purposes of editing in modern digital studio environments, it is usually undesirable to lay down initial tracks in this way. This is where the audio interface comes in. An audio interface usually has several inputs which allow for multitracking into a DAW: if there are six channels on your interface, for example, it will record six independent channels in your DAW. This is a critical concept in modern recording workflows: multitracking allows you to maintain a separation between sounds when they are recorded, making it possible to later balance them relative to one another, to apply effects to individual sounds without affecting others, or even to overdub individual tracks within a larger mix without affecting the other tracks. Once your mixing/editing/processing is done, you can then use the DAW to merge all of these tracks into a single file.

But mixers and interfaces can definitely work together! For live recording, it is common to plug your instruments into a mixer, set your levels to ensure a good mix, and then connect the mixer's stereo outs to the interface to capture a stereo recording in the computer. In home studios, though, it is far more common to use an interface alone: connecting each instrument directly to the interface so that you can capture them all separately, ensuring the ability to go back and tweak your mix later. So for our purposes, it feels like it's virtually always a stronger bet to build your personal recording setup with an interface as the hub rather than a mixer.

Note that some mixers do provide USB or other digital outputs to connect directly to a computer. Many of these, such as several members of Allen & Heath's ZED series mixers, only send the Master Stereo output over USB...so while they're great for capturing live mixes, they do not allow for true multitracking in the way a typical interface does. Devices like that merge all of your tracks into a single stereo file, and you'll have no ability to treat sounds separately from one another in your DAW (the same conundrum we described above regarding analog mixers!). There are, of course, yet other mixers that do allow you to multitrack into a DAW, however: Zoom's Livetrak series mixers and Keith McMillen's K-Mix, for instance, allow you to record all of their channels separately in a DAW, making them a great combination of both workflows. Presonus's Studiolive series of mixers is also a great place to look for a device that can handle both workflows equally well.

Now that we've highlighted some of the finer points of the mixer v. interface debate, you can start to consider what sort of recording interface you would need for your own purposes. When it comes to making a final decision, it is best to consider what you need from three critical features: the inputs, the outputs, and the overall sound quality.

All About Inputs

One of the key factors in picking an interface is determining how many inputs you need, and what sort of things you'll need to plug into them. A singer-songwriter with a mic and an electric guitar has different musical needs than a musician with a studio full of synthesizers—and so, each would likely benefit from a different audio interface. You should choose the number of inputs on your interface in part by determining how many sound sources you need to record at one time. If you're planning to record your music one instrument at a time, for instance, it may not be necessary to buy an interface with eight inputs. On the other hand, if you're recording several synths or drum machines simultaneously, you'll need to make sure that your interface can accommodate all of them. Simple enough!

Next, you'll want to consider what types of sound sources you're plugging into your interface. Specifically, in this regard we can usually divide sound sources into three different categories: sources with line-level output, sources with instrument-level output, and sources with mic-level output. Line-level devices include most mixers, keyboards, synthesizers, and drum machines; instrument-level signals include electric guitars, basses, and other instruments with passive pickups; and naturally, mic-level signals typically original from microphones. Out of these, line level is the highest of all—followed by instrument level, and then mic level.

It's worth noting that Eurorack modular synthesizers often have much hotter output levels than any of these listed signal types...but worry not! You can read some thoughts about that in this article, as well as this one, which focuses on ideas about connecting your modular synth to your audio interface.

Interfaces can have any combination of mic, instrument (sometimes labeled "Hi-Z"), and line-level inputs. Because the level (loudness) of each source is so dramatically different, they each have different needs for recording: more specifically, instrument and mic-level signals require a significant amount of gain (level boost) for optimal recording. Usually this boost is provided by a preamp with variable gain, which in many cases is part of the interface itself. So when picking an interface, it is important to be sure you wind up with not just the right number of inputs, but the right type of inputs. Luckily, interface manufacturers are usually quite straightforward about the types of inputs their products include—so just a quick look at their published specifications should tell you what you need to know. They'll tell you how many XLR mic inputs there are, how many Hi-Z instrument inputs there are, and how many line-level inputs there are on any given interface.

Returning to our examples above: the singer-songwriter with a mic and an electric guitar well may only require an interface with two inputs. Most likely, they will want one input that will accept mic-level signals, and one input that will accept instrument-level signals. At that point, they will be able to plug their mic and guitar into the interface at one time, capturing each at an optimal signal level. There is a wide range of interfaces that could suit this artist: the ESI MAYA22, for instance, could both be solid choices on a budget, while the Universal Audio Apollo Solo could also work spectacularly, albeit at a slightly higher price (with a number of additional niceties); the Focusrite Scarlett 2i2 could make an excellent middle ground.

The musician with a studio full of synths, however, will have different needs. Let's say, for instance, that they want to be able to record four of their synthesizers at one time: they'll most likely want an interface with at least four line-level inputs (or eight, if the synths each have stereo outputs). This musician may not be concerned with having mic or instrument-level inputs. They could, for instance, opt for an ESI U168XT, MOTU Ultralite, or something as fancy as a Universal Audio Apollo x8.

A quick note: sometimes, a individual input on an interface may have the option of operating at mic, instrument, or line level—usually allowing you to change the behavior by flipping a switch or pressing a button. Again, just check out the published specs for the interface you're looking at, and things should become clear.

What About Outputs?

Once you're settled on the number of inputs you need, it's time to consider how many outputs you need. Choosing this is fairly straightforward: it's mostly a matter of knowing what type of speaker setup you'll use, and knowing whether you plan to use any external effects when recording.

Speaker-related demands are fairly straightforward. Most small studios work exclusively in stereo: if you're only doing stereo mixes, you most likely need two outputs for your monitors. Additional outputs can be useful for a number of reasons, though: extra pairs of outputs can easily be set up to assist in A/B testing mixes on different pairs of monitors, for instance, or for sending independent mixes to other musicians in your studio. Additionally, if you're planning to work with more complex speaker arrangements, more outputs may be required. If you're mixing in 5.1 surround, for instance, you'll most likely want an interface with six outputs: five for main speakers and one for a subwoofer (though 5.1 can be set up in slightly different ways). Some major DAWs do provide the option for surround sound output, and even if you aren't a film composer, it can still be a blast to experiment with mixing in these more peculiar contexts.

Additional outputs can also be useful if you plan to utilize external effects processors. Those looking to route their interface through outboard effects, such as reverb or compression, will need one interface output per mono send and one input per mono return. By assigning the computer audio tracks to the right output on the interface and sending back into the interface after your favorite effect processor, it’s possible to add external effects to projects in a DAW. So if you have a rackmount or pedal-format effect processor that your music requires, there is most likely a way to get it hooked up with your interface.

Getting an interface with multiple sets of outputs doesn't have to be expensive. The ESI MAYA44 USB+, for instance, is a straightforward, four-in, four-out line-level interface. The Focusrite Scarlett 4i4 offers four line outputs and a mix of mic/instrument/line-level inputs at a still quite affordable price. The iConnectivity Audio4c is another excellent choice: with four mic/line inputs, four line outputs, and a headphone output, it packs an amazing amount of connectivity into a portable package.

Sound Quality

Inputs and outputs aside, there is the further matter of sound quality. This ties in closely with one of our largest practical deciding factors, which we have only discussed in part so far: budget. With interfaces, sound quality does correlate with price to some degree. Some aspects of sound quality are subjective, such as the tonal difference between one preamp and the next. It is true that more expensive interfaces do tend to have better-made preamps with lower noise floor, but generally, interfaces on the more affordable end of the spectrum will do fine for the typical home studio.

Built-in meters on MOTU's 8A audio interface.

Built-in meters on MOTU's 8A audio interface.

Of course, there are some more objective ways to assess sound quality as well. One of the most obvious and important measures of quality to consider are sample rate and bit depth. Entry-level interfaces often operate no higher than 44.1kHz sample rate with 16-bit bit depth. Luckily, this quality is perfectly fine for many applications: after all, that is CD-level quality, and if you plan to release your projects digitally, recording to 44.1kHz/16-bit will be perfectly sufficient. But if you're working in other professional contexts, higher resolution may be necessary: sound for film typically requires 48kHz or 96kHz sample rate and 24-bit bit depth. Similarly, many professional recording studios tend to run their sessions at 88.2kHz/24-bit—so in short, if you're collaborating with others, knowing the resolution audio that they will require is a big part of the puzzle. That way, you can always ensure that your collaboration goes as smoothly as possible.

Top-of-the-line interfaces such as the Universal Audio Apollo x16 will allow up to 192kHz/24-bit operation, while many interfaces on the lower end of the spectrum (~$100 or so) will only be capable of 44.1kHz, 16-bit operation. There are still, of course, exceptional cases: MOTU's M2, for instance, records up to 192kHz/24-bit and, at the time of writing, costs only $199.95. Focusrite's Scarlett series, mentioned several times in this article, also offers a great combination of overall sound quality and price across the board. And of course, there's plenty of space inbetween the lowest and highest price points: if you only need a couple of input or output channels, Universal Audio's Apollo Solo, Antelope's Zen Q Synergy Core, and even SSL's 2 and 2+ interfaces all provide stellar sound quality at a wide range of intermediate price points.

Tying It Together: Final Considerations

These big three things aside (inputs/outputs/sound quality), there are of course other considerations to keep in mind.

Another aspect to consider is how the interface will connect to the computer, whether by USB, Firewire, Thunderbolt, PCI Express, etc. Of these, USB is most convenient for many users, and is certainly the most common—though more and more Thunderbolt, USB 3.0, and USB-C interfaces have become available as time has progressed. Interfaces can also be great for recording with an iPad or iPhone. Interfaces such as Focusrite’s iTrack Solo, for instance, have been designed for use with iPads or other mobile devices The iTrack Solo specifically contains two Focusrite preamps, great for use with mics and guitar in particular.

As mentioned before, some (but not all!) interfaces also come with MIDI input and output jacks in addition to the audio ins and outs. This MIDI in and out with provide MIDI to and from a computer or MIDI-equipped instrument via the 5-pin MIDI jack. If you only need MIDI for a few instruments, having this in your audio interface will save you from buying a separate MIDI interface. And of course, it’s also worth considering whether the interface will be gigging or staying put in the studio. If it will be traveling, the best choice would be a compact, lightweight, and durable interface, such as the Focusrite Scarlett series (again, a great value for the overall sound quality, build quality, and I/O count).

In the end, every situation is unique—and your personal combination of musical needs will play a strong role in determining what your ideal interface looks like. Even given the breadth of musical diversity that we have seen, though, odds are that there is an interface out there suitable for anyone's individual needs.