Samplers and sample-based synthesizers have been around for more than three decades, and during this time these types of instruments have radically transformed the musical landscape. Frankly, it is impossible to imagine what the world of music would be like today had sampling never been invented. From the early experiments of avant-garde composers to hip-hop to techno—a seemingly simple concept of using pre-recorded sound as a starting point of a creative process has been nothing but transformative, and it remains among the most vital tools in a musician/composer/sound designer's arsenal to this day.

In this article, we take a look at sample-based synthesis, and its history, as well as explore a variety of instrument designs based on this approach. We will also address the creative benefits of sample-based instruments, and outline their nuanced relationship with music and culture. But before we get into the weeds, let’s begin with some basic definitions.

Defining Sample-Based Synthesis

Generally speaking, sample-based synthesis is a method of sound synthesis that involves using pre-recorded audio fragments as the basis for creating new sounds. The core idea implies taking a small segment of recorded audio—a sample—and then using various processing techniques to alter and transform it. Any sound can be a viable source for the technique, be it a recording of an acoustic and electronic musical instrument, a voice, or an entire environment. The length of a sample varies case by case, and it can be as short as a single cycle of a waveform or several minutes long. The duration largely depends on the memory capacity of the given instrument, as well as the particularities of a concrete sound design task.

While the range of processes involved in the modification of sampled sounds varies from instrument to instrument, there are a few core techniques that are universal—namely pitch-shifting, adjusting the duration of the sound, time-stretching, looping segments of the sample, filtering, as well as applying modulation signals such as envelopes, and LFOs to dynamically change various aspects of the sound. Some sample-based instruments also include effects such as reverbs, delays, and distortions that foster an even greater transformation of the original source. Moreover, sampled sounds can be layered together or combined with other digital and analog sound sources (e.g. periodic waveforms).

Many advanced sampler instruments support a feature called multisampling, which is a special sample-based synthesis technique used to capture and reproduce the nuances of an existing acoustic or electronic instrument or any other sound source. In multisampling, the sound source is sampled at multiple levels of intensity, pitch, and articulation, capturing a wide range of possible sonic variance. For example, to accurately reproduce the sound of a flute, the sound engineer would record the instrument playing at different amplitude levels, from soft to loud, across its full range of the instrument. At each level, they may also opt to capture unique expressions of the instrument such as blowing techniques, legato, and vibrato. Each recorded amplitude level, pitch, and articulation technique would be saved as a separate sample, so that a performer can later recall them at will via keyboard input. Pitches mapped to the keyboard according to the original instrument's range, loudness is accessed via velocity, and articulations can be switched on with dedicated keys/commands.

Origins

With many other synthesis methods, it is relatively easy to pinpoint an original inventor or a group of inventors. Sample-based synthesis techniques, however, appears to have organically migrated from one technology to another pretty much since the beginning of recorded sound.

Nearly all early electronic music composers experimented with magnetic tape as a means of composition, but perhaps it is Pierre Schaefer's musique concrète that can be regarded as the closest early practice to modern sample-based synthesis. The basic principle of the technique involved recording ordinary sounds on tape, and then slicing, collaging, and manipulating the recordings to create original pieces of music. And while musique concrète is rather a technique of composition, it laid the conceptual and practical groundwork for the future of sampling. Favored by many composers at the renowned BBC Radiophonic Workshop, the method was used to create some of the most iconic sound effects and music, including the theme music for "Doctor Who," as well as sound effects for "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" and many other television and radio programs.

[Above: a Mellotron MkII; image via the official Mellotron website.]

The "tape" era also produced what can be considered to be the first popular commercial sample-based instrument—the Mellotron. Introduced in the early 1960s, Mellotron was a keyboard instrument that used a series of magnetic tape strips to reproduce the sounds of various instruments and other sounds. Pressing a key would trigger a tape strip to play back a pre-recorded sound. The instrument featured a separate tape strip with an individual playhead for each key on the keyboard, allowing you to play the recorded sounds at different pitches—and to play polyphonically.

Originally designed for simulating the sound of a large ensemble by a single musician, the Mellotron found a wide appeal for its distinctive sonic character which was a natural effect of the mechanical playback of magnetic tape. Over the years, many renowned musicians incorporated the instrument into their work, including The Beatles, King Crimson, Pink Floyd, Yes, David Bowie, Radiohead, and countless others. The tape-based sampler is still widely used today, with the latest model (the M4000) released in 2007. Moreover, there are a few software and digital hardware versions of the instrument which are more affordable, namely the M4000D and Mellotron Micro (each produced under the Mellotron brand name), as well as the Manikin Electronic Memotron.

Perhaps the first digital sampler was created by Electronic Music Studios (EMS) in 1969. The MUSYS, designed by Peter Grogono, was a modular style instrument specifically intended for playback and manipulation of pre-recorded sounds. The core of the MUSYS was a pair of Digital Equipment’s PDP-8 12-bit minicomputers, which had a memory capacity of only 12kb (a lot back then, but a tiny amount by today's standards). Over the next few years, five different revisions of the MUSYS were made, improving the performance and usability of the system. However, only a handful of compositions were created with the machine, and in 1978 its development halted. Nevertheless, MUSYS became an important milestone in the evolution of sample-based instruments, and throughout the '70s, more instruments of that nature started to appear—including the Computer Music Melodian created by Harry Mendell in 1976.

The Turning Point: Fairlight CMI and NED Synclavier

Perhaps the most groundbreaking machines to embed sampling into the culture for good were the CMI—created by Australian company Fairlight—and New England Digital's Synclavier.

Fairlight was founded by Kim Ryrie and Peter Vogel who, inspired by the sounds produced by analog synthesizers like Moog, set out to create a digital instrument that was easier to control, and that had a rich, expandable sonic palette. The pair acquired a commercial license to the Qasar M8—a digital synthesizer created by Tony Furse around 1975 that was equipped with a powerful processor and was capable of generating complex waveforms via additive synthesis. After a few years of development, in 1979 Fairlight unveiled their first commercially available sample-based synthesizer, the CMI (Computer Musical Instrument).

[Above: a Fairlight CMI IIX]

The Fairlight CMI looked like no other synthesizer at the time, comprising a full-range keyboard, a CPU block, a computer keyboard, and a monitor that could be navigated with a futuristic light pen. The device came with a library of pre-recorded sound files to be used as source sounds, but importantly, it allowed its users to capture any audio (less than a second long), edit it, and play it at different pitches. Although prohibitively expensive (the first version cost around $35k at the time), the instrument gained wide recognition, and many celebrity musicians purchased it. Among the first users of the instrument were Peter Gabriel (whose home for a period of time was used as Fairlight's distribution hub in Europe) and Kate Bush, who was the first artist to deliver a hit single created with CMI. A number of classic samples from the instrument's library became prominent elements in a range of pop songs of the era. A particularly popular one was the "Orch1" which captured an orchestral hit of Stravinsky's Firebird.

It is also important to note that while sampling was a primary synthesis method in CMI, the synthesizer was also equipped with a flexible waveform editor which allowed you to freely draw waveshapes, and a powerful resynthesis engine. Moreover, CMI featured the first screen-based sequencer, so that complete multi-track compositions could be produced on it.

[Above: a New England Digital Synclavier system]

New England Digital's Synclavier arrived a year earlier than the CMI, however, upon its release, it did not feature sampling but rather presented a powerful platform for additive and FM synthesis. However, the Synclavier hosted programs on removable cards, and thus its functionality could be drastically changed by simply loading a different software. A number of third-party developers created unique programs for the instrument, and the company itself, inspired by the success of the CMI, created a sampler program that allowed the instrument to be used in a very much similar way the Fairlight's invention.

Similar to the fate of CMI, the limited amount of production units of the instrument ended up in the studios of professional musicians. Nevertheless, its impact on the musical instrument industry, and on culture in general, is vast. Among the notorious Synclavier users were Frank Zappa, Laurie Anderson, Pat Metheny, Michael Jackson, and Kraftwerk.

Proliferation of Digital Samplers

Without a doubt, CMI and Synclavier were pivotal in the transition of electronic musical instruments to the digital age. Yet, while the companies continued the production and modification of the machines well into the early '90s, many other companies saw the potential of sampling technology, and throughout the 1980s more and more sample-based instruments started to appear that tackled the issues of portability and affordability. In 1981 the California-based company led by Dave Rossum, E-Mu Systems, introduced the Emulator series.

[Above: an E-mu Emulator I keyboard-based sampling instrument]

Emulator I was an 8-bit sampler with a built-in keyboard which was at least thrice more affordable than the CMI and Synclavier. Given the popularity of the instrument, the company proceeded to develop and improve it further with the last version, Emulator IV, discontinued only in 2002. Moreover, E-Mu Systems created the first commercially successful sample-based drum machines, the SP-12 (1985) and SP-1200 (1987).

Another important name in the history of sample-based synthesis is Ensoniq. The company debuted with a keyboard-style sampler Mirage in 1984, which within its first year of existence sold more units than all other companies combined. Undoubtedly, the big reason for this was the incredible affordability of the instrument (in relative terms), however, the instrument also didn't lack in features, and had similar features to its pricier competitors. Importantly, Mirrage was a hybrid instrument that combined digital sampling with characterful analog filters. The Mirage was replaced in 1987 with the EPS. Until the dissolution of the company, Ensoniq produced a range of affordable yet powerful instruments, primarily utilizing sample-based and wavetable techniques, and often incorporating the Mirage-style hybrid analog-digital architecture.

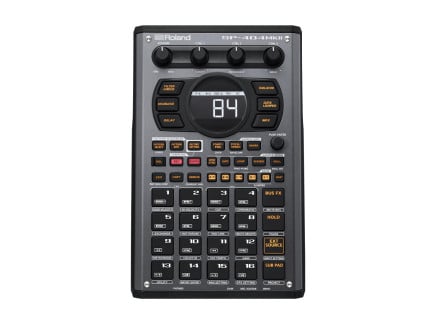

Lastly, it would be an incomplete revision of the history of sample-based instruments if we didn't mention the iconic MPC developed by Roger Linn for Akai. With the first version (the MPC60) released in 1988, the MPC is the longest-produced sampler, still available today in a few variations such as MPC One+, MPC Live II, and MPC Key.

[Above: an Akai MPC60]

What made the MPC particularly special is a complete rethinking of the interface. Linn's goal was to create an instrument that was intuitive in use and didn't require its users to bury themselves in a highly technical manual. The now-classic design of the instrument featured 16 large performance pads organized in a 4x4 grid, a big screen, plus a modest collection of control elements—all packed into a compact enclosure that allowed the users to produce finished pieces of music without the need for an additional mixing console. The sounds were stored on floppy disks, allowing the users to easily swap samples. The sampling memory of the original MPC60 was only 13 seconds, and Linn initially expected musicians to lay out short single-hit samples along the grid to be played like a drum machine. However, users quickly started to capture longer loops, pioneering new production techniques and contriving new forms of electronic music and hip-hop. By all accounts, MPC is one of the most influential electronic musical instruments of the 20th century.

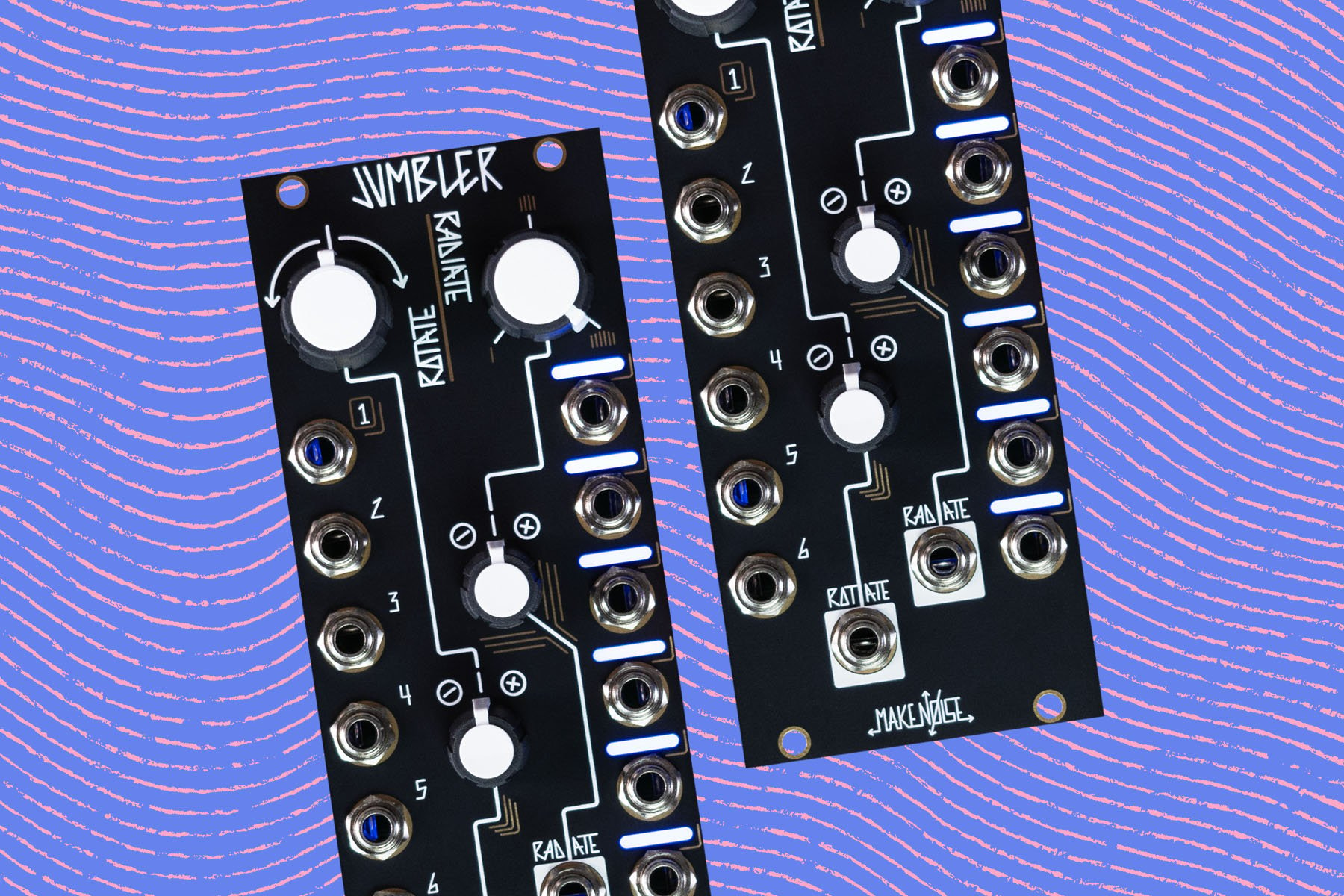

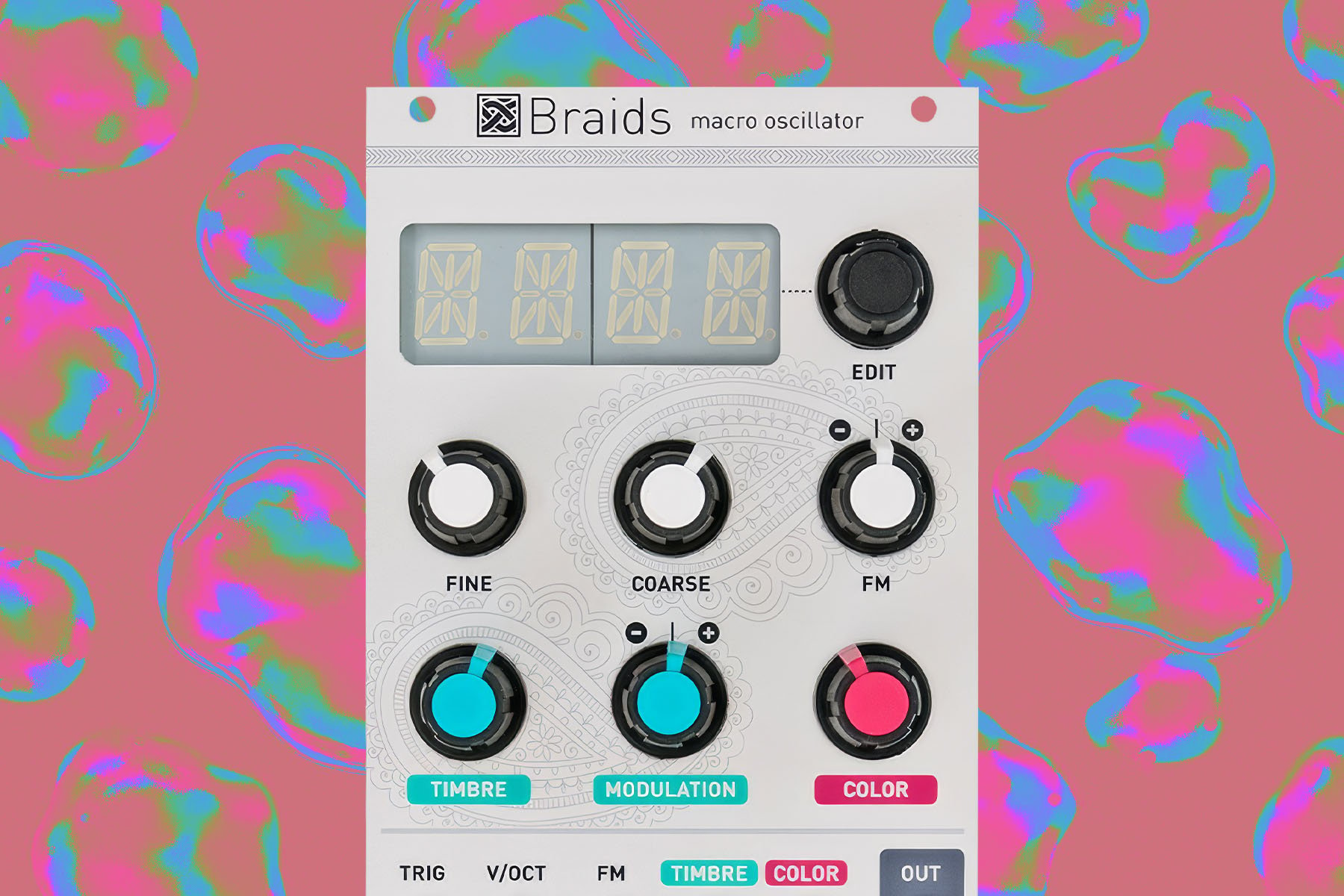

A lot has changed since those early days of sample-based synthesis. The processing power of today's machines is phenomenal. With the rapid advancement of personal computers, sampling has become merely one type of musical task an average modern laptop, tablet, or smartphone is capable of. That said, a number of hardware instruments offer unique ways to incorporate sample-based synthesis in both sound design, and performance contexts. For example, the Swedish manufacturer Elektron redefined performance-oriented sampling with instruments like Octatrack and Digitakt. The company Polyend has also been developing a line of powerful sample-based instruments such as Play, Tracker, and Tracker Mini with a skew toward live use, and intuitive production. Moreover, there is a vast and growing range of sample-based tools in modern modular systems, namely the Eurorack format. Modules such as Make Noise Morphagene, Rossum Assimil8or, Squarp Rample, ALM Squid Salmple, 4MS Stereo Triggered Sampler, and many others provide an extremely robust and open-ended foundation for sample-based sound design and composition, each in their own way.

Types Of Sample-Based Instruments

As you may have guessed by now, sample-based synthesis comes in a variety of forms and shapes, and the same premise of using pre-recorded sound material as a basis for creating new tones is approached quite differently depending on the manufacturer, and the intended purpose of the instrument. In this section, we outline a few distinct approaches to sample-based synthesis.

Let's start with a classic sampler. A sampler is a rather general term that we attribute to any instrument if it is capable of recording, storing, editing, and playing back audio. However, there is a class of sample-based instruments that does away with recording sounds directly, focused on playback and editing of already captured sounds. Historically, these instruments have been dubbed romplers—an amalgam of the words "ROM" (read-only memory) and "sampler". Among the most well-known romplers are instruments like Korg M1, Roland JV-1080, Ensoniq KT-88, and E-mu Proteus. While romplers by design don't allow you to record sounds directly into them, the format is particularly well-suited for handling multi-sampled instruments. A modern example of this comes in the form of widely popular software instruments such as Kontakt from Native Instruments, and MachFive from MOTU. These are commonly used for realistic simulations of existing acoustic and electronic sounds including vintage synthesizers, guitars, flutes, drum sets, full orchestras, and more.

It is also not uncommon to see hybrid instruments that combine sample-based and other forms of sound synthesis, typically subtractive. For example, the aforementioned M1 allowed you to layer pre-recorded sounds with digital oscillators. In the 1980s, Roland also devised a peculiar method for combining pre-recorded and synthetic sound sources, which they called Linear Arithmetic Synthesis, or LA synthesis for short. First implemented in the famed D-50, the method implies blending an attack transient of a sampled sound with a sustained periodic waveform to create complex and realistic timbres.

Sampled sounds are a particularly favored source for percussion synthesis, and quite a large number of drum machines employ it either partially or exclusively. A well-deserved appeal of sampling, in this case, has to do with its unrestrictive nature as a sound source. A modern drum machine can host thousands of recorded sound snippets that can vary from electronic and acoustic percussion to textures, tones, short loops, and chord stabs, thus allowing you to construct a complete track entirely on one instrument. Drum machines that are equipped with a sampling engine, a sequencer, and in some cases other synthesis modules are commonly referred to as grooveboxes—a term coined by the Roland Corporation in 1996 to describe the MC-303. [For more on this topic, check out our article about Roland's role in the history of the "groovebox."]

Lastly, some instruments (Elektron Octatrack, Polyend Tracker) support real-time sampling, thus enabling you to record external sound sources live, and nearly instantaneously process, manipulate, and rearrange it in a variety of ways. This is a vastly powerful technique that can spice up performance.

Pros and Cons

Like any sound synthesis method, the sample-based approach has its strengths and weaknesses. Among the former are certainly versatility, and ease of use. Sample-based instruments typically have an extensive and, importantly, extendable sonic palette. Moreover, it can be very time-saving, since you can get access to an already complex sound by simply loading the right file, and not having to tune a swarm of oscillators, assign modulation sources, and dial in an array of parameters.

Among the limitations of the approach is the reduced level of variance in sampled sounds. Unlike, say, analog oscillators which naturally have a level of subtle deviation, recorded audio will sound exactly the same every time they are triggered. Having said that, it is important to indicate that there are techniques that can be used to combat this, e.g. employing light randomization of parameters or sprucing things up with cleverly applied modulation. It is also crucial to underline that as a digital method, sample-based synthesis is dependent on the technology used. At low sampling rates and bit depth, samples lose resolution and become noisy and distorted. Yet again, this lo-fi effect is occasionally welcomed and even desired as it is treated as a contributing factor to the distinct character of an instrument.

In any case, with decades of experience, modern manufacturers have a clear understanding of what makes sample-based synthesis unique, and both strengths and weaknesses of the approach are explored creatively in contemporary instruments.

Looking to get a sampler of your own? Be sure to check out our Hardware Sampler Buying Guide for our top suggestions for adding sampling to your music at a wide variety of price points.