For many, the Yamaha CS-80 is the pinnacle of vintage synthesizers. Released in 1977, its massive feature set coalesced into a trifecta of layered sound design, novel expressivity, and powerful character. History is filled with brilliant synthesizers. Why is the CS-80 so often referenced as the best synthesizer ever made? What did it do nearly half a century ago that earned such a prominent place in music history? Why does it continue to inspire synthesizer development well into the 21st century?

Let’s explore CS-80’s past and learn how this extraordinary instrument came into being. Once we have our bearings, we’ll decode its panel for a better understanding of its sonic capabilities and its uncanny ability to channel eloquent and thoughtful electronic compositions. Finally, we’ll compare the CS-80 to modern hardware and take a look at how you just might embed a little CS-80 magic into your music.

Before the CS-80: The Yamaha GX-1

The technological bedrock for the CS-80 was struck during the development of Yamaha’s GX-1. Released in 1975, the GX-1 comes from an era when proto-polysynths first began to emerge, such as the Oberhiem Four Voice and the Moog Polymoog.

Determined to rule the synthesizer space, Yamaha reportedly spent the modern equivalent of over 23 million US dollars developing the GX-1. That enormous investment led to an 18-voice, 184-keyed, quad-timbral behemoth weighing in at over 850 pounds. Imposing a thoroughly intimating stature, the GX-1 looked like a musical battle station, seemingly more at home on the Star Trek Enterprise than on any stage.

[Above: the behemoth Yamaha GX-1, originally branded as Electone. Image via Yamaha's website.]

The GX-1’s performer was armed with three keyboard manuals and a pedalboard—much like an elaborate organ. The highest was a three-octave “solo” keyboard that was monophonic. Next came the two five-octave keyboards, each with eight-note polyphony and two oscillators per voice. The foot-operated pedal manual spanned 25 notes and was monophonic.

It was priced at $60,000 US dollars (over $350,000 today), thoroughly eliminating any feasibility as a consumer product. But the GX-1 was never really meant for a wider market. More so, it was a foundational statement of what was possible, and what Yamaha was capable of accomplishing. It was a vehicle for developing the technology for what came next: the Yahama CS series synths.

Yamaha's CS Series Synthesizers

Yamaha quickly implemented its new tech in consumer-focused packages that were more manageable in price and size. However, these products still weren’t cheap, and they certainly weren’t small—both factors which played a part in the short production life of the CS synthesizers.

Now, we're going to focus on the higher-end, polyphonic members of the CS family—all of which were released in 1977 and shared technology derived from the GX-1.

First, we need to outline some of the key points that made these instruments so groundbreaking as a whole. These were among the first fully integrated polyphonic synthesizers altogether: earlier polyphonic instruments were most commonly built around a modular structure, but the CS series (and some contemporaries) offered polyphonic keyboard control and macro controls that impacted the timbre of each voice equally...creating a uniform sense of timbre across all voices.

Additionally, the CS series were some of the first commercially-produced instruments that featured preset memory. They accomplished this through the use of complex internal switching and dozens of fixed voltage divider circuits—effectively mimicking various front-panel slider settings with the used of fixed resistor values to achieve different sounds at the push of a button. By modern standards, this is a crude and cumbersome approach—and one that's not dissimilar to the type of preset memory built into earlier experimental Moog modular synthesizers, or Don Buchla's Music Easel—but for the time, this was a revolutionary capability.

That said, let's now take a look at several members of the CS family.

Yamaha CS-50

[Above: the Yamaha CS-50. Images via Perfect Circuit's archives.]

The smallest and most affordable of the series was the CS-50. A four-voice, 49-key polysynth, the CS-50 weighed approximately 75 pounds. Each voice offered a single oscillator. It had aftertouch, though not the polyphonic aftertouch found on the CS-80. The CS-50 came with preset sound selection, but no user memory slots.

Yamaha CS-60

[Above: the Yamaha CS-60. Images via Perfect Circuit's archives.]

The CS-60 doubled the CS-50's polyphony, with a total of eight voices. It had 61 keys, above which sat the same delectable ribbon controller found on the CS-80 (more on that later). It also came with preset capability and a single patch memory slot—allowing users to create a single custom preset, which could be modified at will using a compartment of small sliders that mirrored the main front-panel controls (see images above).

However, the CS-60 still fell miles short of the CS-80, lacking the prime features of polyphonic aftertouch, as well as the second voice layer.

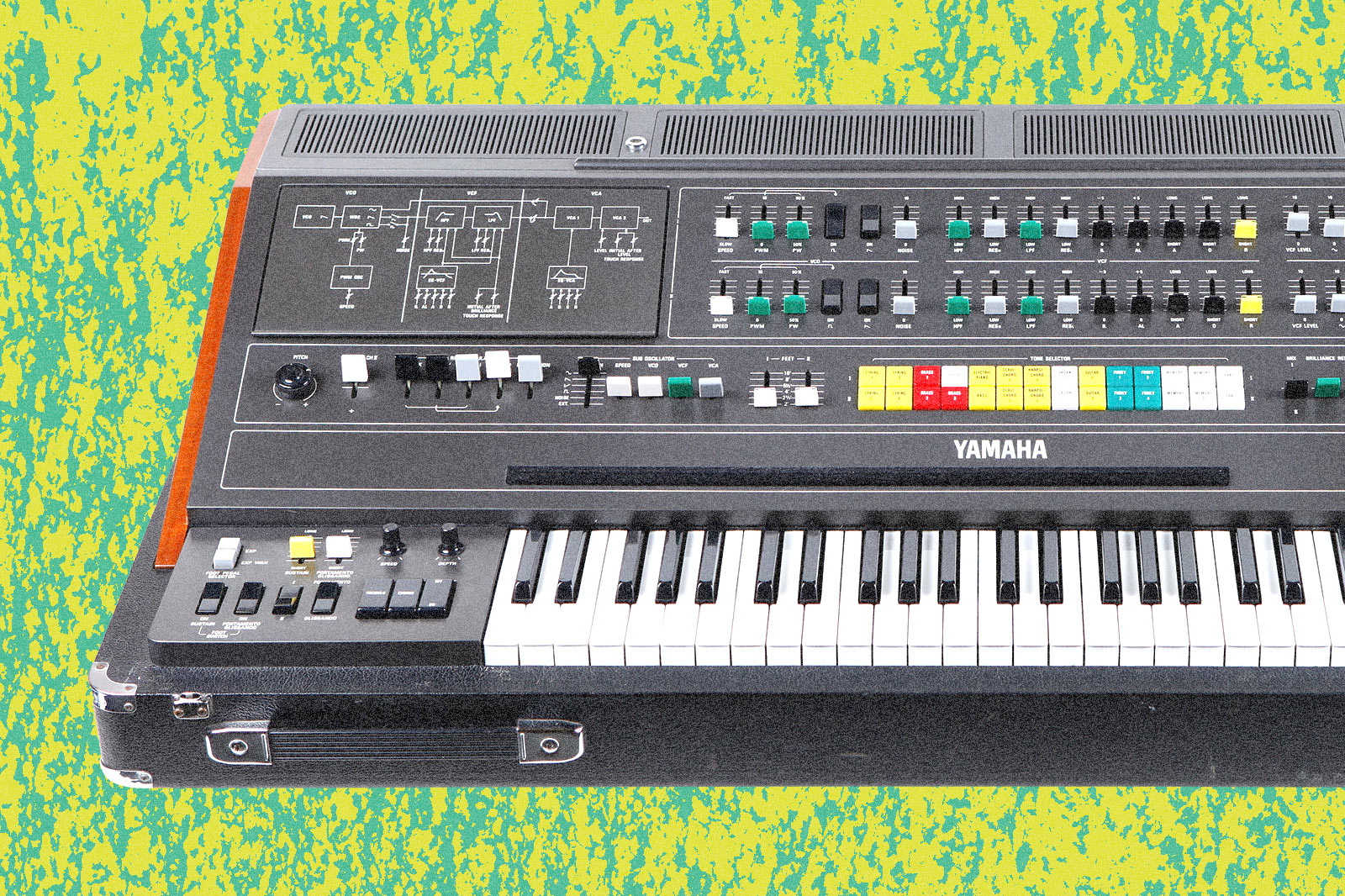

Yamaha CS-80

We’re going to go deep into the CS-80’s panel and functionality in a bit, but for now, suffice to say it was the non-compromising, no-holds-barred model of the series. Like the CS-60, it had eight-note polyphony, but each "voice" had two independent layers—essentially offering bi-timbral support and doubling its sound design capabilities.

[Above: the iconic Yamaha CS-80. Images via Perfect Circuit's archives.]

It had 61 weighted keys with polyphonic aftertouch, a ribbon controller, and increased expressive modulation potential when compared to the other CS synthesizers. Its 22 presets were complemented with four user memory slots. Lastly, the CS-80 had the broadest frequency range of the three synths. All that functionality came in a package that weighed over 200 lbs and cost $6,900 (roughly equivalent to $36,000 today).

End of production

Unfortunately, the CS-80 lost its technological edge after only a few years, and Yamaha ceased production in 1980. The CS-80 was astronomically above the average musician’s budget and inconveniently large, though this wasn’t always a deal breaker back in those days, especially for keys; organs and electric pianos weren’t exactly light. Rather, it was largely a series of rapid technological developments and the emergence of forward-thinking competition that doomed CS-80 production.

In 1978, Sequential Circuits released the Prophet-5. It didn’t bring the voices, sound design flexibility, or level of expressive control of the CS-80, but it was cheaper at $3,995 (roughly $20,000 today), much smaller/lighter, and had a vastly improved patch memory system based on a microprocessor. In fact, it is likely that the Prophet-5 was the first commercial musical instrument that featured an embedded microprocessor altogether.

[Above: an original Sequential Circuits Prophet-5—in many ways, the archetype for all programmable polyphonic synthesizers that followed.]

The Prophet-5 is an incredible instrument with its own impressive legacy. In fact, many consider it to be the true turning point went synthesists didn’t have to rely on human memory to get back to their favorite sounds. However, it does seem severely outclassed when compared to the CS-80. It’s not appropriate to call one of these instruments better than the other; they’re vastly different. It seems that Sequential Circuits simply had the right technological idea at the right time—and ultimately, the basic control concept in the Prophet 5 became foundational to most analog synthesizers that followed.

CS-80 in the wild

The CS-80’s short production lifespan did not stop it from being used by some of the biggest names in pop music, like Michael Jackson (on Thriller, no less), Stevie Wonder, and many others. But, one of the most interesting showcases of the CS-80’s abilities is found through its appearences in the works of prominent pioneers of early electronic music.

A personal favorite is Brian Eno’s “By This River,” in which the CS-80’s uncanny mix of lush melancholy and dynamic brilliance briefly steals the spotlight in a dance with a beautifully bluesy Rhodes.

And then there’s Vangelis. Undeniably, there’s no better-known champion and steward of the CS-80 legacy than the works of the late master composer and synthesist. Its expressive tones on the Blade Runner soundtrack followed Deckard through his futuristic odyssey, channeling a timbre that exudes huge waves of emotion while unapologetically maintaining the sound and character of a synthesizer. And that really sums up the CS-80's prime directive: to bring the playability and depth of expression found in acoustic instruments to synthesizers—all the while adding more tonal variety than anything else. At the time, little came closer to achieving "ultimate analog electronic instrument" than did the CS-80.

Decoding the CS-80 Sound

The revered CS-80 sound rests on three fundamental pillars: sound shaping, expression, and character. The knob-per-function panel unlocked a plethora of sound-sculpting tools that provided an incredible amount of control. Two oscillators, five filters, two VCAs, an LFO, tremolo, and chorus were all at the player’s disposal. Many of these tools were organized in two discrete channels, inviting thorough use of layering two sounds to create powerfully rich tones and complex organic pads with a life of their own.

Then there was an unprecedented level of support for expression, namely the polyphonic aftertouch. To grasp the expressive benefits of polyphonic aftertouch, it’s important to differentiate it from the more common monophonic aftertouch.

Aftertouch, which is the modulation of synth parameters using key pressure, is usually implemented as channel aftertouch. Monophonic aftertouch affects all notes equally, regardless of which key you press down on, similar to the functionality of a pitch wheel. Polyphonic aftertouch, such as that on the CS-80, applies modulation on a per-key press basis, dramatically increasing the potential for finer expressions using varied pressure on individual key presses. Most synths today, even premium gear, only offer monophonic aftertouch, and the synthesizers that do support polyphonic aftertouch often do not come equipped with a polyphonic aftertouch-capable keybed (though this tide is slowly turning). The CS-80’s implementation of polyphonic aftertouch in the '70s was a huge statement about the expressive potential of synthesizers.

The CS-80 also added additional expressive avenues via an excellent ribbon controller and highly-adjustable key tracking and velocity parameters. These tools fostered truly dynamic performances; you didn’t just make sounds with the CS-80; you built full-on reactive instruments from the ground up.

Lastly, the CS-80 bathed all this sonic possibility in a thick wash of character. CS-80s are easy to pick out in a mix for all the right reasons. They're often lush, dense, delicately saturated, and organically moving. There is also a strong tonal signature that’s instantly recognizable, even on the CS-50 and CS-60.

The Yamaha CS-80 Architecture In Detail

Full appreciation of the CS-80 requires a little time spent digging into its specific functions. The feature set is so vast in both breath and volume that you’d be forgiven for mistaking this for a modern synth write-up. But it’s important to consistently remind yourself that this all happened in 1977 on one of the first polysynths.

Layers of Tone

Although the CS-80 had eight-note polyphony, it had 16 voice boards. This allowed each of the CS-80’s eight voices to utilize two dedicated voices simultaneously, allowing you to create two distinct sonic layers, or "channels." Each channel had a single oscillator capable of saw or square shapes, and noise, which fed into per-channel high-pass and low-pass 12dB sloped filters with envelope controls. After the VCF, each channel added the ability to add a sine wave for a little extra fundamental oomph on one or both layers. Finally, each voice layer had a dedicated VCA, including ADSR envelope controls.

[Above: image describing layer balance settings from the Yamaha CS-80 user manual.]

A global mix section gave control over the balance of the two layers. A global low-pass filter provided one last touch of tonal shaping, also helpful for unifying the overall timbre. You could transpose each layer to add musical harmonics, like 5ths, to a patch. A layer two detune knob facilitated more nuanced frequency shifts between the two layers for deep, rich chorusing effects.

Having so much individual control over each synth layer essentially made the CS-80 bi-timbral and, in tandem with the synth’s capacity for expression, facilitated big and organically complex sound design.

Expressive Control to the Extreme

Equally as unique for the time as the CS-80’s dual-channel synth engine was its number and quality of expressive control parameters. We’ll begin with the per-channel expressive controls and then move to the global parameters.

Keybed filter modulation

A global keyboard control section gave the CS-80 advanced. This key tracking, implemented in a gradual curve, meant the filter cutoff and overall volume could be modulated depending on a note’s position on the keybed. This was useful for getting more natural behavior out of a patch, such as increasing volume and brightness in the lower registers, giving the bass power and clarity while taming the otherwise-harsh higher notes.

Polyphonic aftertouch and velocity for each layer

Each layer had a “touch response” section. Because the CS-80’s global touch response section focused on pitch and LFO modulations, these channel touch response controls were the primary way of using velocity and aftertouch to modulate the raw tone of the CS-80.

The channel touch response sections each included four faders, with two dedicated to velocity and the other two affecting aftertouch. Each set had a brilliance fader, which was equivalent to an modulation amount control for the low-pass filter, determining how much high-frequency content to let through based on velocity or aftertouch. A set of level controls allowed increased volume based on velocity and/or aftertouch.

Global velocity and aftertouch

Beyond the individual layers, a global touch response section had four additional expression controls. The first was an initial pitch bend for each note modulated by velocity. Depending on a mix of the initial pitch bend fader level and how hard a key was pressed, the player could insight a very subtle upward frequency movement or a dramatic twang. The remaining three controls were all dedicated to aftertouch modulations and linked to the CS-80’s versatile global LFO. Faders for VCO pitch and VCF cutoff both leaned on a speed fader that modulated LFO speed with aftertouch, facilitating everything from gently wobbling frequency variations to otherworldly hypnotic swirls using key pressure.

Ribbon controller

[Above: the Yamaha CS-80's ribbon controller; image via Perfect Circuit's archives.]

The CS-80 included an intuitive ribbon controller for pitch expressions that went beyond the capabilities of the keys. Wherever you initially placed your finger was the starting point, and it was responsive enough to pull off all manner of pitching techniques, from slow slides to speedy trills. What took it a step further was the ribbon behavior unlocked using the CS-80’s sustain modes. The ribbon could affect the entire sound or only the currently held-down note. This added more polyphonic functionality as you could have harmonies set on a long release unaffected while adding pitch movement to a lead note.

Ring modulator

The ring modulator on the CS-80 was profoundly musical. It added glassy and/or metallic fluctuations, but it also did something else that’s difficult to describe. When paired with the dedicated envelope, the ring modulator caused a very organic type of movement, coaxing out yet another distinct layer of character from the CS-80. A modulation level control determined how much effect the ring modulator had on the sound. A speed fader set the maximum speed of the modulation. Attack, decay, and depth faders allowed for control of that speed over time. When you hear it, it’s easy to imagine becoming lost for hours with this one feature alone.

LFO

The CS-80 had a versatile global LFO, labeled "sub-oscillator" on the panel. The LFO waveshapes included sine, saw (up and down), square, noise, and the option to use an external signal. Baked into the LFO section was a speed control for LFO rate and mod level controls for VCO pitch, VCF cutoff, and VCA level. Several modulations found throughout the CS-80 panel are relative to the settings of the global LFO.

Presets and User Memory

The CS-80 came with 22 presets and the ability to store four single-layer user patches. That means if you were using the full might of both layers for a patch, you could define and save two distinct full patches per layer (which could be combined with pre-set or user-defined sounds on the other layer). Global controls were not storeable, and had to be recreated after switching to a user patch. A little context reveals why this was an impressive achievement for the time, despite the obvious limitations when processed via a modern lens.

[Above: the open and closed user preset compartment on Yamaha's CS-80. Images from Perfect Circuit's archives.]

As mentioned before, in 1977, presets weren’t an expected feature on a synthesizer. The CS-80 was one of the first. Without digital methods, Yamaha implied an interesting workaround to achieve recallable user memory. In the top-left of the CS-80, a hinged panel opened to reveal four sets of mini-fader controls that mirrored the main panel’s oscillator layer controls. Because they were so much smaller than the main panel faders, the user memory controls didn’t provide the same fidelity as the main panel, but it worked for getting in the same ballpark. Basically, when you switched to a "user preset" slot, the synthesizer would suddenly ignore the large front-panel controls in favor of the respective set of miniature sliders. Wild.

Comparing to the Present

The CS-80 remains heavily sought after as one of the best and most enjoyable synthesizers. Anecdotes from owners of this legend always seem to include more emotional feedback than technical jargon, implying time spent with the CS-80 is a treasured experience.

Of course, as a treasured vintage instrument, a real CS-80 is outside the budget of most working musicians; these instruments easily command prices above $20,000...and sometimes far higher. So, if you want to explore the potential of a CS-80, where can you look?

Comparing the CS-80 to modern synthesizers reveals some limitations of the times, but also several opportunities for improvement in current gear design.

First, where are all the new synths with discrete layering control? There are multi-timbral options (though not nearly enough) but switching between layers or timbres usually requires momentum-crushing menu diving or an incomprehensible panel that shows parameters for the previous timbre. The dedicated per-layer controls of the CS-80 invited real-time layer tweaking on the fly. We need more of that today (but don't worry—we're not entirely without this functionality...more on that shortly).

Thankfully, we are seeing an increase in polyphonic aftertouch in modern instruments, as well as other expressive features. But it’s puzzling that this isn’t a modern standard on every poly synth with keys. The CS-80 is still setting standards nearly half a century later.

The complete feature set of the CS-80 has yet to be recreated in any one piece of gear, though there are products that can get you very close, if not beyond its capabilities. Let’s dig into just a few options for how you can get a similar hardware experience with a more manageable budget.

Black Corporation Deckard's Dream MK2

[Above: a spectacular demo of the Deckard's Dream by YouTuber, musician, and friend of Perfect Circuit, Ricky Tinez.]

Black Corporation’s Deckard’s Dream is perhaps the most faithful recreation of the CS-80's sound architecture workflow. Its dual layer setup precisely matches the CS-80’s. It’s got the same parameters and layout, but most importantly, Deckard’s Dream, without a doubt, captures the magic of CS-80’s gorgeous sound.

It also comes with several modern must-haves for a synth of this caliber, including patch memory, MPE support (great for those expressive aftertouch performances), plus a handful of features accessed through a small screen.

What you don’t get is the ring modulator or large front-panel ribbon controller. And while Deckard’s Dream thoroughly recreates the CS-80’s polyphonic aftertouch control, you need to supply your own polyphonic aftertouch keyboard or MPE controller.

UDO Super Gemini

[Above: a demo/exploration the UDO Super Gemini by Hazel Mills.]

While Deckard’s Dream is the best recreation of the CS-80, the UDO Super Gemini is panning out to be its most ambitious spiritual successor. Similar to the CS-80’s story, the Super Gemini derives much of its DNA from an earlier sibling, the UDO Super 6, and essentially gives you the equivalent of two Super 6s and then some.

As with the CS-80, the Super Gemini offers two instrument layers, each with two of UDO's richly smooth DDS oscillators. That gives each of the Super Gemini’s 20 voices access to four oscillators, if desired. Each layer has its own discrete analog/digital hybrid signal path, complete with high-pass and low-pass VCFs and a VCA. Each layer also has a full set of dedicated controls, bringing back the layered sound-sculpting of the CS-80 and its fostering of a present workflow. That's a big deal.

The CS-80-sourced inspiration continues with a ring mod and a similar pitch ribbon, capable of trills and affecting only the held-down notes. A prioritization of expressivity is front and center with the Super Gemini, as it comes with a polyphonic aftertouch keybed, which is still a rarity, and a comprehensive expressive control section to the left of the keybed.

The Super Gemini also packs tons of modernized gems like per-layer delay freeze, an extravaganza of modulation paths, and UDO’s exceptional binaural features for unmatched stereo effects. It’s exciting to see something that hits so close to the awe-inspiring CS-80 design and philosophy in developement with a focus on modern sounds.

ASM Hydrasynth Deluxe

The ASM Hydrasynth is a versatile polysynth with a lot of value. One its standout features is a polyphonic aftertouch keyboard and a touch ribbon, helping reach CS-80 levels of expressivity.

The Hydrasynth Deluxe specifically comes with 16 voices, and it’s bi-timbral, which you can use similarly to the CS-80’s two layers. You don’t get the same immediacy as the other synths on this list, as the Hydrasynth requires switching back and forth between layers for sound shaping. However, this drawback is heavily mitigated by the Hydrsynth's light ring encoders, enabling the panel to represent each patch accurately as you switch between timbres.

Additionally, the Hydrasynth has great overall UI/UX, with a sensible panel layout that’s fun and easy to work with. You certainly won’t find this feature set anywhere for less.

An Alternative Approach: MPE

Expression being such a big part of the CS-80 sound means that you can’t get there in earnest with a standard midi controller or keyboard, even with channel aftertouch. The good news is this is a really good era to get more expressive with your synths due to the widespread adoption and development of MPE (Midi Polyphonic Expression). MPE has a similar mandate as the CS-80 did in the '70s: to bring the powerful use of musical expression to synthesizers. Expressive techniques like bends, slides, wiggles, velocity, and even release velocity are unlocked with an MPE-supporting synth and controller, of which there are many to choose from.

Closing Thoughts

It’s mind-boggling to imagine what it must have been like to experience a CS-80 in the '70s. So many sonic avenues were opened with its release, only to be largely abandoned for decades. Perhaps Yamaha flew too close to the sun with its early magnum opus, discouraging similar projects. We’re seeing a positive shift in the right direction, but what would be different today had the CS-80 remained feasible as a consumer product?

Vangelis himself expressed regret that the CS-80 wasn’t developed further, but also hinted as to why. He expressed that the CS-80 was a true instrument, and with that came the difficulties of learning to play that instrument, just like any other. Difficulty is not particularly marketable, especially when in competition with instant results—a famous story about the evolution of synthesizer design in the late '70s and into the '80s and '90s.

But perhaps accepting and conquering that learning curve is what it takes to master and fully experience something as organic and nuanced as the CS-80. The fact that such experiences even exist in synthesizers is worth celebrating.