It should come as no surprise that we at Perfect Circuit are fascinated by sound. This fascination often manifests among us and our friends as an obsession with electronic instruments. Eurorack systems, keyboard synths, and drum machines all provide their own deep sets of options for exploring how to create and organize sound from the ground up. Many of us fall in love with these instruments because they temporarily satisfy an incurable itch to explore unheard sounds—to create exploratory tones and textures completely different from the sounds of daily life. In this exploration, it can become easy to forget just how bizarre the real world actually is...and how bizarre the real world can actually sound.

Field recording can be a spectacular way to break out of your musical habits and find new inspiration. In the practice of field recording, we focus on finding and capturing interesting sounds in the real world rather than building sounds from scratch. This of course has practical applications in film and related industries, but can also be used for exclusively creative purposes.

Album art for Ian Wellman's Bioaccumulation

Album art for Ian Wellman's Bioaccumulation

Recordist and musician Ian Wellman recently came by our shop to talk about his experience in field recording, demonstrating some great tactics for capturing sound from the real world. Ian's latest album, Bioaccumulation, utilizes field recordings as material to explore the relationship humans have with their environment—providing a fresh way of approaching the collection and treatment of sound. Field recording can break us away from the realm of oscillators, filters, and modulation and encourage a type of deep listening that reveals to us the complexity and beauty of real-world sounds...and with the right set of tools, you can capture any sound for use as you see fit. Use ambient recordings as textures to augment your music, create trigger-able one-shots, capture complex sonorities for further processing and mangling, or simply appreciate these sounds for what they are.

In the above video, Ian walks us through some of his own raw recordings and the mics and techniques used to capture them. Let's first talk about some of the basic gear you'll need to start working with field recording—after that, we'll dig into Ian's examples a bit more, and think about how and when these ideas could be useful in your own musical work.

Getting Started: What You'll Need

Of course, one of the most important pieces of gear to acquire as you start your adventure in field recording is the field recorder itself. Field recorders can serve many purposes and come in many shapes and sizes, but their primary function is to record sound from microphones and store it without the need for a studio-style audio interface or computer. Because the purpose of a field recorder is for the most part limited to capturing audio, these devices can be fairly small and portable. You can think of them as being similar to audio interfaces—they have preamps, analog-to-digital converters, and digital-to-analog converters—but instead of recording to a computer, they record to some form of internal storage (such as an SD card).

One of the most popular field recorder brands is Zoom, who produce a wide range of recorders for professional recordists and hobbyists alike. Perhaps their most popular series of products is the Handy Recorder line—a set of highly portable field recorders with a ton of features that make them instantly usable to recordists of any experience level. There are several recorders in this product line, but let's take a closer look at some of the most interesting ones: the H4n Pro, H5, and H6.

One of the most popular Handy Recorders is the H4n Pro, a 4-channel field recorder with a built-in coincident X/Y stereo microphone pair (we'll get into exactly what this means a bit later in the article). This makes capturing real-world sound as simple as setting a level and pressing the record button—and with two additional XLR-1/4" combo jack inputs, it gives you the ability to also add your own external mics and instruments. It has a dedicated headphone/line output for monitoring your recording levels...and because it can be powered from AA batteries, the H4n Pro is a killer choice for musicians and recordists who need a compact field recorder that is ready to go at a moment's notice (I personally keep one on me all the time).

The next step up in the Handy Recorder line is the H5. The H5's feature set might immediately appear to be very similar to the H4n: it's another small, handheld recorder with a similar user interface and two external inputs. However, one of the H5's key features is its built-in microphone system. While the H4n's microphone pair is permanently connected/hardwired, the H5 has removable microphone capsules—making it such that you can easily swap out different capsules for capturing different types of sound in different environments. The H5 includes their XYH-5 X/Y capsule (similar to the H4n's built-in microphones), but depending on your needs, you could add a number of other options, including the SGH-6 Shotgun mic capsule, MSH-6 Mid/Side capsule, EXH-6 Dual XLR/TRS external input capsule, or others. This is a pretty awesome feature—it means that you can maintain the portability of something like the H4n, but gain some of the advantages of using additional microphones while still keeping your overall footprint and price relatively low. We typically recommend the H5 as a good starting point because of how easy it is to experiment with different mic configurations; this makes it super easy to learn how best to capture any given sound through experimentation.

Another recorder worth mentioning is the H6, the current top of the line model in the Handy Recorder series. The H6 utilizes the same system of exchangeable capsules as the H5, but features four additional XLR/TRS inputs (rather than the H5's two XLR/TRS inputs). This plus the easy-to-see color display makes the H6 a stellar choice when you need to capture several channels of audio simultaneously—by using the combination of Zoom's mic capsules and the external inputs, you are easily prepared for a wide variety of recording scenarios. For quickly capturing sounds at a moment's notice, the H5 is a stellar choice—but if you need to record several sources independently all at once, the H6 well may be a better option.

Zoom's field recorders have a host of other handy features; they can all act as USB audio interfaces, can be mounted on standard camera tripods (or even directly on cameras), and fit into a small enough space that it's easy to keep them on your person. The recorder itself is only part of the equation, though: and microphones are the other vital piece of the puzzle. We've talked a little bit about the microphone capsules available for the H5 and H6, but let's look more closely at different types of microphones and talk about how they can be used in both practical and creative applications.

Shotgun Microphones : Hearing from Afar

Shotgun microphones are one of the most powerful tools of the field recordist. Shotgun mics usually have a supercardioid / lobar polar pattern—meaning that they reject the vast majority of sound to their sides and rear, but have an extended pickup area directly to their front. This means that they do an excellent job blocking out the majority of environmental noise, and allow you to capture sound from a very focused area wherever the mic is "aimed."

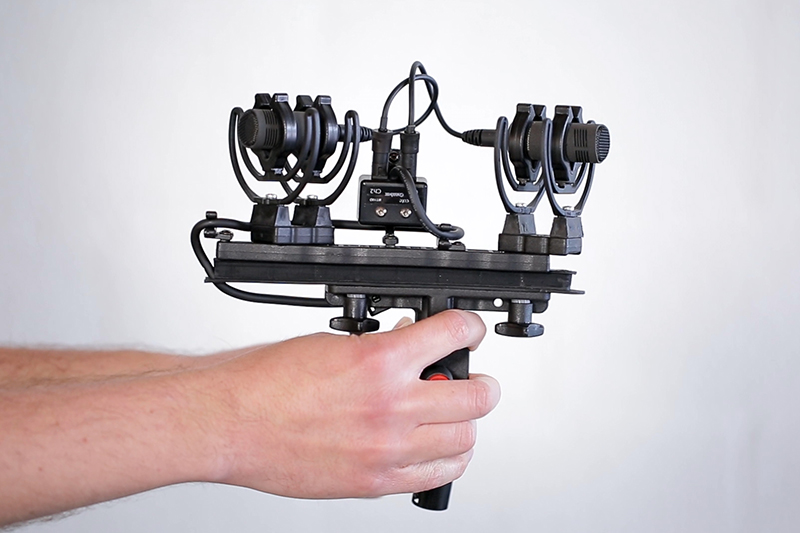

Ian Wellman with a shotgun-based M/S array

Ian Wellman with a shotgun-based M/S array

Shotgun mics are commonly used for capturing speech in uncontrolled environments, since they can so easily cut through environmental noise in order to pick up the sounds at which you are "aiming." There are usually better choices for capturing dialog in a studio—but if you need to record speech from a distance or in an otherwise noisy environment, shotgun mics are an excellent tool.

Of course, for creative recordists, there are other huge advantages: because these microphones' pickup area is so concentrated, it becomes easy to capture specific sounds from otherwise dense environments, even from a considerable distance. So if you need to record the sound of a creaking solar panel that you can't quite get to, or want to hear the sounds of an animal that you don't want to disturb, or simply want to catch the minute details of a small sound hiding in dense mess of surrounding activity, a shotgun mic could be a useful tool.

Zoom has two shotgun-style capsules for the H5 and H6. The SGH-6 is a standard mono shotgun mic capsule, great for capturing audio at a distance. The SSH-6 is a stereo shotgun capsule based on a mono shotgun capsule and bidirectional capsule—but more on M/S recording in a bit. First, let's take a look at some other stereo recording techniques.

Stereo Recording Techniques: ORTF & X/Y

Of course, because shotgun mics are intended to pick up highly localized sounds and reject their surrounding environment, they are only monaural. This is great for picking up specific, isolated sounds, but not so great for creating a sense of space. If your goal collecting field recordings is to use them to capture a sense of ambient space, it might be wiser to consider using a pair of standard condenser microphones (so as to better emulate the way that we hear). And of course, there are plenty of ways to accomplish this.

An ORTF array, great for a wide, clear stereo image

An ORTF array, great for a wide, clear stereo image

One popular stereo microphone technique, as demonstrated by Ian in his presentation, is referred to as ORTF (named after the Office de Radiodiffusion-Television Francaise, the broadcasting organization where the technique originated). In an ORTF microphone pair, two cardioid microphones' capsules are spaced 17cm apart and are angled 110 degrees apart from one another. This provides a fairly realistic stereo image not terribly different from the way that we hear. By using cardioid microphones (which primarily pick up sound from in front of them, but reject sound from behind) at a fairly dramatic angle from one another, the sonic overlap between mics remains fairly small and phase differences do not make themselves apparent even if the recorded channels are summed to mono. This technique is fairly easy to set up, and results in a wide, spacious-feeling stereo image perfect for evoking the sense of really being in a space.

Another related and similarly easy stereo technique is called X/Y, which uses two cardioid microphones directly above and below one another, typically angled with 90 degrees of separation (each pointed 45 degrees to either side of your target sound source). It provides a narrower, less spacious feel than ORTF configurations, but is still great for capturing small areas—and best of all, since sound waves arrive at each capsule simultaneously, there is virtually no risk of phase cancellation issues between microphones...making traditional X/Y configurations highly mono-compatible.

Zoom's X/Y capsules (both those on the H4n and those available for the H5 and H6) offer a couple of options for adjustment of the X/Y displacement angle. While 90 degrees of rotation is common for X/Y pairs, wider angles can be used in order to capture a wider stereo image. In the case of Zoom's XYH-6 X/Y capsule, you can switch between 90 degree and 120 degree configurations, each of which gives a very different sense of distance and orientation in the captured space while maintaining a clear focus on sounds in the center of the pickup area. Zoom also makes an X/Y capsule for iOS devices, the iQ6, making it easy to turn your phone into a fully capable, stereo field recorder.

Advanced Stereo Recording: Mid/Side

X/Y and ORTF techniques are easy, reliable ways to capture a great sense of space in your recordings. One downside to ORTF, XY, and many other stereo techniques is that once they have been recorded, you cannot do much to modify their stereo spread. While reasonably mono-compatible techniques can offer the ability to narrow their spread, you cannot do much to widen them once the sounds have been captured. With mid/side, though, you have quite a bit of room to tweak your stereo image after the fact. Mid/Side (M/S) configurations, though, provide a stellar combination of mono-compatibility and stereo width that can be easily varied in post.

An M/S array comprised of a shotgun and bidirectional microphone

An M/S array comprised of a shotgun and bidirectional microphone

An M/S mic array is comprised of one directional mic (often cardioid, though even more highly directional mics like shotguns can also be used) and one bi-directional mic (sometimes called a "figure-of-eight" mic), which picks up sound evenly from two sides but rejects sound along its central axis. By positioning the two mics so that the bi-directional microphone picks up sound from the left and right of the source (hence side) while the other microphone is directly aimed at the source, each microphone can be used to "fill in the gaps" of what the other misses. In theory, this provides a good direct capture of your sonic focal point (via the Mid microphone) and a good capture of the ambient space (via the Side microphone). Of course, if you simply use the recorded sound with both mics' audio in mono, nothing spectacular happens—but by applying some additional processing, some pretty magical things emerge.

In M/S recordings, the Mid microphone remains panned mono/center. The Side audio, though, is duplicated to two channels, which are respectively panned hard left and right. The level of the duplicated channels should be linked, and one of them is phase inverted. The net result is pretty spectacular: the phase differences between the left and right channels create an extremely wide, unnatural stereo image which is balanced/corrected by the Mid channel. By increasing or decreasing the volume of the side channels, you can alter the apparent width/depth of the stereo effect. This enables the creation of a truly dramatic stereo image—one that often sounds pleasant and dramatic for both musical and sound-based recording. And of course, for those of you using recording techniques for the purpose of creative soundmaking—try animating/automating the Mid and Side channel levels on an M/S recording. When done intentionally, the results can produce a particularly dramatic stereo image that swells, recedes, and changes shape altogether.

Zoom's MSH-6 capsule provides an easy-to-configure M/S setup in a single, small capsule, great for capturing a controllable stereo image with minimal setup. Additionally, the SSH-6 capsule provides a modified M/S configuration with a shotgun mic in the Mid position, providing all the advantages of a mono shotgun (focus, isolation) with a controllable level of additional ambience. And best of all, the H5 and H6 have an M/S decoder built in—so you can get an idea of what your final stereo sound might be like without needing to wait until you're at home editing the audio in your DAW.

Zoom also makes an M/S capsule for iOS devices, the iQ7, which makes it easy to experiment with cool M/S tricks without needing any specialized equipment.

Extreme Distance: Parabolic Microphones

Parabolic microphones are super cool. Parabolic mics use a large parabolic dish to focus sound waves onto a microphone which faces toward the center of the dish. The dish acts as a way to focus distant sounds onto the microphone, dramatically increasing the microphone's natural sensitivity. This makes parabolic mics an excellent choice for recording distant sounds. Common applications include recording sounds a great distance away which cannot be disturbed or directly interfered with—such as birdsong, or on-field sound during sporting events.

The trouble with parabolic mics is that their frequency response is highly dependent on the size of the parabolic dish. Given that sound occupies physical space (it has measurable wavelengths, which we more commonly think of as "frequency"), the size of the reflective surface physically affects the microphone's ability to capture low frequencies (which have longer/larger wavelengths). The larger the dish, the better the low-frequency response—but for practical sizes of parabolic mic, low-frequency response is fairly weak.

If you need to capture sounds at a moderate distance but need higher audio fidelity, a shotgun mic might be a better solution—but for birdsong and capture of other natural sounds, the limited frequency response of a parabolic microphone is often outweighed by its superior performance capturing over long distances.

Novel Recording Tricks: Contact Mics & Hydrophones

Here's where we really begin to depart from the "practical" aspects of sound design and dive deeper into the realm of the weird. So far we've mostly been discussing techniques for capturing sound as we typically hear it in the real world—and while there is a lot of beauty to be found in the sounds of everyday life, there are parts of the world that we cannot naturally hear. Diving into these sounds can be a huge source of inspiration, and can provide textures and timbres completely unlike anything you've heard from any synthesizer or conventional field recording.

As Ian notes in his demonstration, one of the great ways to explore these "unheard" sounds is via contact microphones. Typically composed of a simple piezoelectric transducer, a so-called contact mic is meant to be affixed to a surface to translate its physical vibrations into sound. This makes it easy to turn virtually any object into a mic—metal sheets, tables, vehicles...everything is fair game. What is particularly interesting here is that the physical object imparts its own acoustic characteristics on the captured sound. So capturing sound through a wooden board will sound completely different from a metal sheet. One of the really exciting parts of using contact mics is the unpredictability of the outcome; so try this out on multiple types of surfaces and see how it goes!

Contact mics come in a lot of shapes and sizes. Some, like Korg's CM-300 are meant to clip onto instruments for connection to tuners, but work equally well for amplifying any clamp-able surface. Crank Sturgeon also makes an assortment of contact microphones geared toward different uses, as well as novel instruments designed with contact mics at their core.

Hydrophones are somewhat similar in concept—but instead of capturing vibrations in the air or on solid surfaces, hydrophones are meant to capture vibrations in liquids. Since sound travels very differently in water than it does in air, this can create a truly alien listening experience. Whether you're capturing sound that originates within the liquid or simply using the liquid as a medium through which to filter sounds from the outside world, hydrophones can provide a great way of hearing a part of the world you would otherwise never experience.

Hydrophones also vary widely in shape, size, and price. High-end hydrophones from companies like Brüel & Kjær can be used down to depths nearing 1000m below the ocean's surface; but simpler hydrophones can also be made from the same types of materials as a typical contact mic, though. Crank Sturgeon's Immersion Sturgeon, for instance, is a great low-cost hydrophone for use in your aquatic sonic adventures.

Hearing the Unhearable: EMF Microphones

EMF microphones are an excellent way to tap into another unhearable corner of the world: electromagnetic fields. Given how immersed technology has become in our daily lives, electromagnetic radiation is everywhere. Radio waves, Wi-Fi signals, cell signals, and much more are constantly floating through the air, completely undetectable to us...unless you use a device that can convert these electromagnetic frequencies into something that we can hear.

EMF mics reveal dense drones, glitches, radio interference, and huge waves of noise all around us. Sometimes they will produces fizzy glitches and sputters; sometimes they produce enormous walls of dense, harsh noise. Perhaps the most exciting thing about exploring EMF signals is that they're almost completely unpredictable—it's hard to know exactly what the electromagnetic activity in any particular area will be like until you start listening. Even very familiar places can suddenly become entirely new, unveiling weird, secret aspects unnoticeable to the bare eye or ear.

SOMA Laboratory's Ether is one of the most interesting EMF devices currently available. Referred to by its creators as an anti-radio, the Ether is designed to tune in to a wide variety of tones outside the realm of human hearing. Its high sensitivity means that it can change sound completely just by slightly shifting its position—so it is great for exploring any area. It has a headphone output, which can be used for monitoring or recording.

Field recording as a practice can of course be used for practical purposes: film, news gathering, documenting sporting events, and much more. But listening to the raw sounds of the real world can also help to reveal the compelling nuance and detail of sounds that might at first seem completely mundane. In the video below, we used a Zoom H5 to capture sounds from around our office and turn them into a rhythmic track of real-world sound effects—but you can use these types of sound for a huge range of other purposes as well.

By capturing real-world sounds and learning about the various tools and techniques used by recordists, it becomes easy to start to hear everyday sounds with a completely new light. And once you're in a headspace that allows you to notice these sounds and have the right tools to capture them, and entire new realm of music and sound making opens up: one that doesn't need to rely on the proscriptive rules of MIDI or control voltage, and instead rewards careful listening and attention to the beautiful and weird noises of the world around us.