In the expansive landscape of musical expression, drone-based music stands out as a unique realm that captures the imagination and shifts the perception of time and space unlike anything else. More than merely a genre, it exists as a sonic universe deeply rooted in ancient traditions, while continually evolving alongside modern technology.

Easily recognizable by its sustained, hypnotic, and ephemeral nature, drone music transcends mere aesthetics; it often resonates with philosophical and esoteric systems of knowledge, serving distinct functions across various cultures. Its origins reach back centuries, crossing global boundaries—from the gentle strumming of the tanpura in Indian classical music to the airy drones of Scottish bagpipe tradition.

On the other end of the spectrum, drone music has become increasingly entwined with electronic music culture, massively spanning 20th-century avant-garde and experimental movements, popular music, and of course countless soundtracks for science-fiction. Synthesizers and samplers have proven to be particularly invaluable modern drone instruments. Although pretty much any synthesizer can be a great drone emanator, over the years we have seen instruments created specifically for this type of music-making, offering a rich palette of unique textures. Soma's Lyra-8, the Ciat-Lonbarde Cocoquantus, JMT NOSC-12, and Elta Music Solar 42 are but a few examples—each created around a distinctive design idea, and unusual sonic character. This is clearly a sign that the synthesizer community deeply cares about drones.

In this article, we'll delve into the mesmerizing world of drone-based music and its byproducts, offering context and texture to this unique sonic realm. We'll trace its roots and follow the intricate threads that weave together East and West, the archaic and the modern. We'll discuss the place of drone music across different cultures, eras, and genres, highlighting the various instruments used to create these trance-inducing sonic landscapes. If you find yourself drawn to elongated ambient soundscapes, by the end of this article, you'll have a broader understanding of these musical forms and, hopefully, a deeper appreciation for them. It really is one of those cases where "less" is "more." So, let's begin.

Defining Drone

Defining drone can seem to be a deceptively simple task, however, the concept is rather layered. A trusted dictionary such as Merriam-Webster offers us a general and serviceable definition of a drone as a deep sustained monotonous tone. While in essence, this is correct, this definition lacks the nuance and complexity that are inherent both to its experiential aspect and its rich historical connotations. Drone has an ancient and widespread history, appearing in various forms across multiple cultures and periods. Drone is fundamental to a number of musical traditions, and its use is often, while by no means always, rooted in ritualistic, devotional, or folk practices. Later in this article, we will explore this aspect of the sustained tone, but for now, let's keep unpacking the term further.

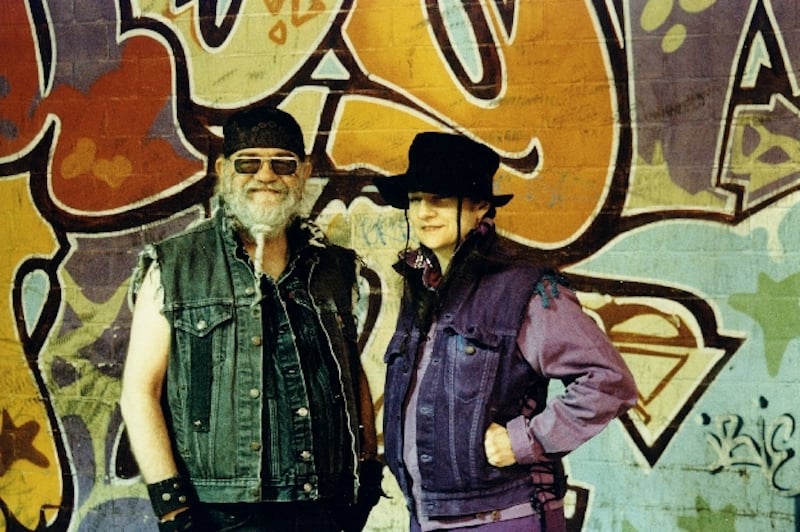

[Above: La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela; image via Mela Foundation. Photo credit: Jutta Brandt 1996.]

One such example would be the widely known Dream House light+sound environment, originally created by the minimalist composer La Monte Young and multimedia artist Marian Zazeela in 1969. The attention-demanding installation features an indefinitely-lasting microtonal drone composed of 32 sine waves. The installation has seen a number of iterations over the years. The current version, located at 275 Church Street, New York marked its 30th anniversary this year.

[Above: a recent note change from the Halberstadt Organ 2/ASLSP performance—on May 2nd of 2022.]

Another note-worthy drone piece of extended duration is John Cage's Organ2/ASLSP (As Slow As Possible). While a typical performance of this piece lasts somewhere between 20 and 70 minutes to a 24-hour marathon, a group of musicians and philosophers adapted the piece for a continuous performance over 639 years. Set at St. Burchardi church in Halberstadt, the piece is played by a custom-built electronically-controlled organ. It began in 2001, and it is scheduled to go on until 2640. Every note change is a major event, and the next one is happening on February 5, 2024—so, mark your calendars for a visit.

Another crucial aspect of a drone is its emphasis on the timbral qualities of the tone. Sure, a continuous monotonous sine wave can pass as a drone, and so can the 50/60Hz electric hum that we tend to avoid in our creative practice. However, drones can come in many varieties—multiple layered tones, shifting and modulating textures, repetitive loops, incessant pulsations, and diverse combinations. The sustained sound can be soothing or dissonant, sparse or heavily dense, serenely soft, or massively loud. The extended durational aspect of the drone allows the sound to unfold and capture the attention gradually. The mind of the listener is freed from following harmonic and pitch changes and is offered a resting place amidst a slowly and subtly evolving sound mass.

Although all kinds of music have a strong capacity to excite us emotionally and psychologically, the effect of drone sounds is so stark and so specific that many world cultures have made it a significant part not only of their musical traditions—it can also be heavily entwined with the mysticism and cosmogony of a given culture. Hence, we would leave off a big aspect of this enigmatic sonic phenomenon if we don't draw at least a few lines that show the connection of sustained tones to the "bigger pictures" of life and the universe.

First There Was Sound: the Esoteric Origins Of Drone

As the modern scientific view on the origin of the universe suggests, right after the Big Bang, the universe was an inhospitable realm where conventional sound, as we understand or perceive it, had yet to exist. This early cosmos was a tumultuous blend of subatomic particles like photons and electrons, along with enigmatic dark matter, all engaged in a chaotic ballet. At this stage, traditional mediums enabling sound propagation were absent. Nevertheless, scientists often discuss the pressure waves coursing through this nascent, expanding universe as "cosmic sound waves." Though these wave-like phenomena wouldn't be detectable by the human ear, they can be likened to sound waves.

At this point, you may wonder, why the heck am I talking about physics here? The possible confusion is understandable, but I assure you my detour into physics is pertinent to our exploration of sound. Music and sound have played major, if not central, roles in the cosmological narratives emerging in various cultures throughout centuries. The "cosmic sound waves" are just one example stemming from the secular physics-driven view of the world. However, the sound of creation is ever-present in countless creation myths and metaphysical apprehensions of the cosmos, life, and creation.

Ok, I need to specify now why this link between sound and cosmology requires a particular spotlight in the context of drone music discussion. While drone sounds have been utilized in various mystical and spiritual traditions, their deep, sustained hum holds unique significance across different cultures.

Sound plays a huge role in Vedic traditions, an ancient Indian spiritual system that became the basis of Hinduism, and indirectly influenced the origination of Jainism, Sikhism, and Buddhism. In the dense web of Vedic knowledge lies a concept of the Anahata Nad which refers to the "unstruck sound," a sound that is not made by two things striking together—a vibration that is said to exist in the universe without a visible source. A similar concept also exists in Sufism under the name Sawt-e-Sarmad, and it is also reflected in the well-known Zen koan "What is the sound of one hand clapping?" While these descriptions don't refer to a sound that can be heard by humans in everyday waking life, they hint toward a sort of continuous eternal sound that permeates everything.

Indian classical music, which even predates the documented forms of Ancient Greek music, reflects this cosmological narrative in the very nature of its organization. Unlike Western classical music, which is often associated with rigorously composed passages and moving harmonic structures, Indian classical music puts an emphasis on improvisation which unfolds around a steady drone. The reference to the cosmological worldview is evident—the creative energy, varied in its moods and colors, bursts freely around an unchanging eternal center.

Drones are also vastly present in Tibetan and Mongolian spiritual practices. Examples range from vocal practices like chanting and throat singing to the usage of specialized instruments like gongs, dungchen horns, and singing bowls during ceremonies, healing sessions, and as an aid in meditative practice.

In the cosmology of Aboriginal Australian peoples, the concept of Dreamtime or "The Dreaming" serves as a foundational element and represents the timeless realm that encompasses the past, present, and future. One of the most vital aspects of the Dreamtime is the Songlines—oral maps that outline the paths across land and sky used by the celestial beings in the process of creation. One of the most well-known instruments that Aboriginal tribes connect with the "Dreamtime" mythology is the didgeridoo—a woodwind instrument that emanates deep harmonically rich, and often rhythmical drones.

Drone is also widely present in Western mystical traditions. A great example of such is the plainsong, also known as plainchant or Gregorian chant, which developed during the early period of Christianity. Rooted in Judaic musical tradition, as well as the Greek modal system, plainsong is characterized by monophonic, unaccompanied vocal lines that follow a free, non-metrical rhythm. While plainsong is not entirely drone-centric in itself, the use of tones sustained for a long period of time, reverberating through spacious religious architecture offers a very similar effect.

The examples mentioned above are only a fraction of cases that exemplify the intertwined relationship between sound and cosmological worldviews, and a droning sound, in all of its variance, symbolizes and epitomizes this link. Let’s transition from ancient practices and understandings to explore the modern adaptations and interpretations of drone music.

Modern Drone

Although many of the ancient musical and spiritual musical traditions have utilized drone sounds for millennia, the term "drone music" primarily emerged in the second half of the 20th century as a descriptor of the novel compositional practices employed by minimalist and experimental music composers. Notably, this is a historic period where Eastern philosophical ideas and practices started flowing extensively westward, inspiring a generation of young artists committed to expanding cultural borders. La Monte Young, the minimalist composer whom I mentioned earlier in the article, is often cited as a founding figure of drone music. With influences ranging from the classical Indian music of Pandit Pran Nath, Schoenberg's and Webern's surrealism, the boundary-pushing jazz of John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, experimental approaches of John Cage, and an overall fascination with Eastern philosophy, and spirituality, Young forged an novel musical dimension exploring sustained tones, microtonality, time perception, and spatial acoustics.

[Above: Eliane Radigue's Triptych—an iconic work of drone-based electronic music.]

La Monte Young was certainly at the forefront of the development of Western drone music, but he was not the only one. Terry Riley, being influenced by similar musics as Young—African and Middle Eastern music, and by Young himself—developed a unique compositional style with a major focus on repetitive structures and sustained tones. Pauline Oliveros explored and connected the droning tones in her compositions with a reflective sonic practice she called "Deep Listening". The music of Eliane Radigue immerses the listener in a dense and extremely slowly changing microtonal sonic milieu. The work of Alvin Lucier often tested the complex dynamics between sound and space. Henry Flynt has created a mesmerizing fusion of avant-garde and hillbilly music with a strong influence of Indian raag and free jazz. Charlemagne Palestine, who prefers the term maximalism to minimalism, creates durational performances and compositions where he builds up complex droning structures out of simple repetitive rhythmic patterns.

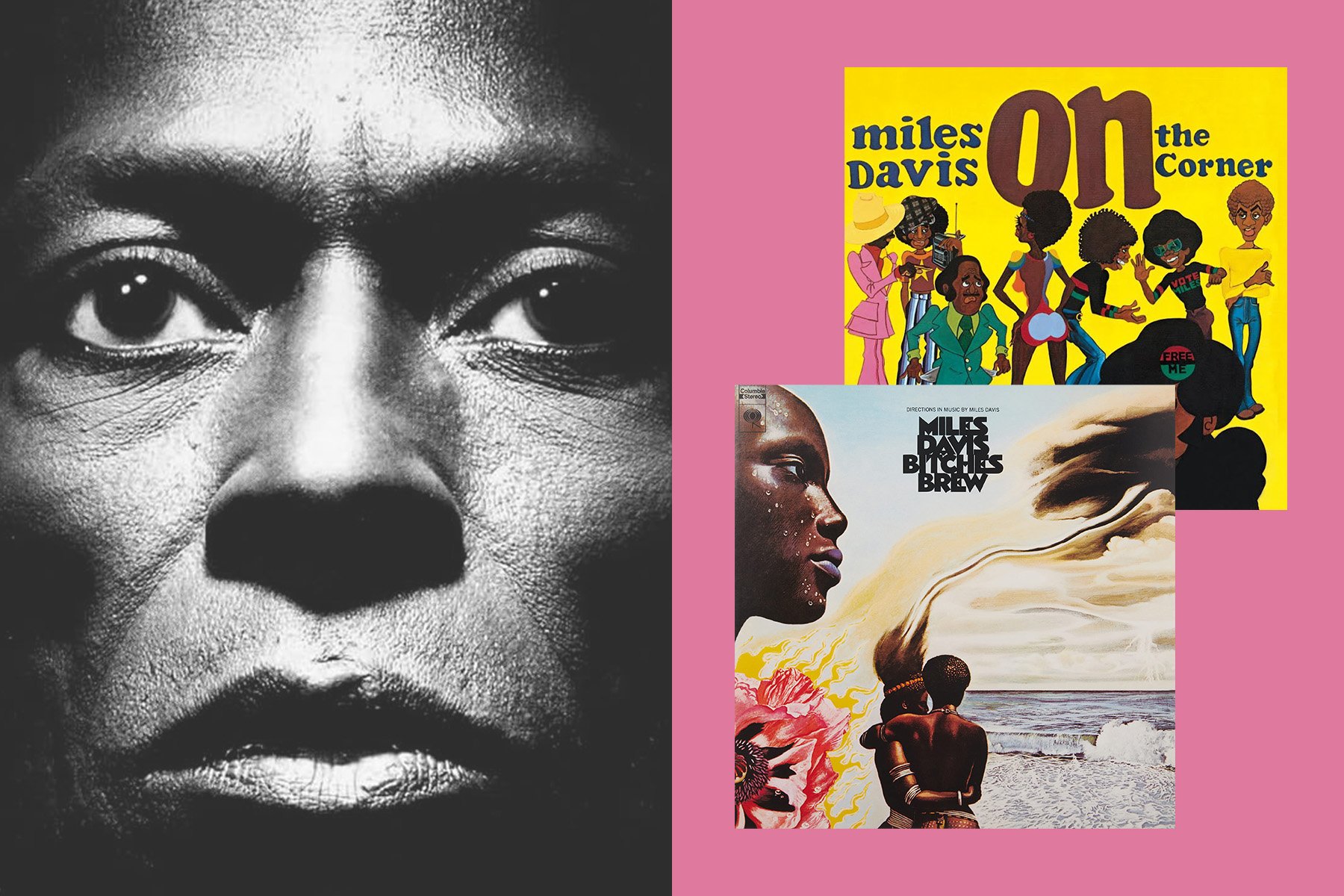

Jazz, especially the more adventurous forms of fit, also featured an embrace of drone among several artists. John and Alice Coltrane, Sun Ra, Pharoah Sanders—all have expanded their musical language by intertwining drone and improvisation. Moreover, artists and collectives like the AMM absorbed the legacy of free jazz, and transformed it into free improvisation—a highly spontaneous musical venture, that often manifests itself in the form of a drone.

The jazz and academic worlds were not the only musical realms that drone has made its way to, it has also had a profound impact on the world of popular and underground music, touching upon nearly every genre. Velvet Underground and The Beatles, as distinctly different in their musical expression of rock music, were among the first to incorporate drone into their songwriting. Brian Eno’s 1979 album Ambient 1: Music For Airports marked the beginning of ambient music. In the '80s and '90s, a diverse array of artists including Sonic Youth, Melvins, Throbbing Gristle, Coil, My Bloody Valentine, Merzbow, and Earth, each in their own way, laid pathways to new musical dimensions, of which drone sounds were certainly a big part of. Today, as the lines between genres get ever blurrier, we have artists like Sunn O))), who take what Alvin Lucier did in the academic world, and bring it to the world of metal.

Such a varied musical palette suggests that the application of drone in composition is multifaceted. In some cases, such as traditional and jazz forms of music, drone grounds the improvisation to a distinct tonal point. On the other hand, experimental approaches sometimes put the entire emphasis on the drone sound itself. Drone can also be used sporadically to accent or emphasize sections of a composition, and create a dramatic transition or a hypnotizing effect.

Instruments Of Drone

Generally speaking, if a musical instrument is capable of producing a sustained sound, it is suitable for drone music. Moreover, with certain techniques like the strumming patterns of Charlemagne Palestine, looping, or bowing, nearly any musical instrument can be adapted for drone. Humans have, however, developed a range of instruments specifically designed to create drone sounds, such as the Indian tanpura and shruti box, Greek aulos and monochord, Australian didgeridoos, Scottish bagpipes, and hurdy-gurdies, which have spread to multiple European cultures. These instruments are centuries, and in some cases, even millennia old.

With the rapid advancements in electrical science in the late 19th century, humanity was on the brink of revolutionizing musical instrument design. The 20th century saw the emergence and evolution of recording and playback technology, electric guitars and keyboards, effects pedals and sound processing units, and synthesizers, altering our interaction with music. Electronic musical equipment, in particular, offered unprecedented capabilities for drone sounds, allowing many instruments to play a sustained tone indefinitely without the need for continuous excitation from a person. Not surprisingly, many early electronic composers, already influenced by Eastern philosophies, viewed tape machines and synthesizers as the ideal tools to convey their musical ideas.

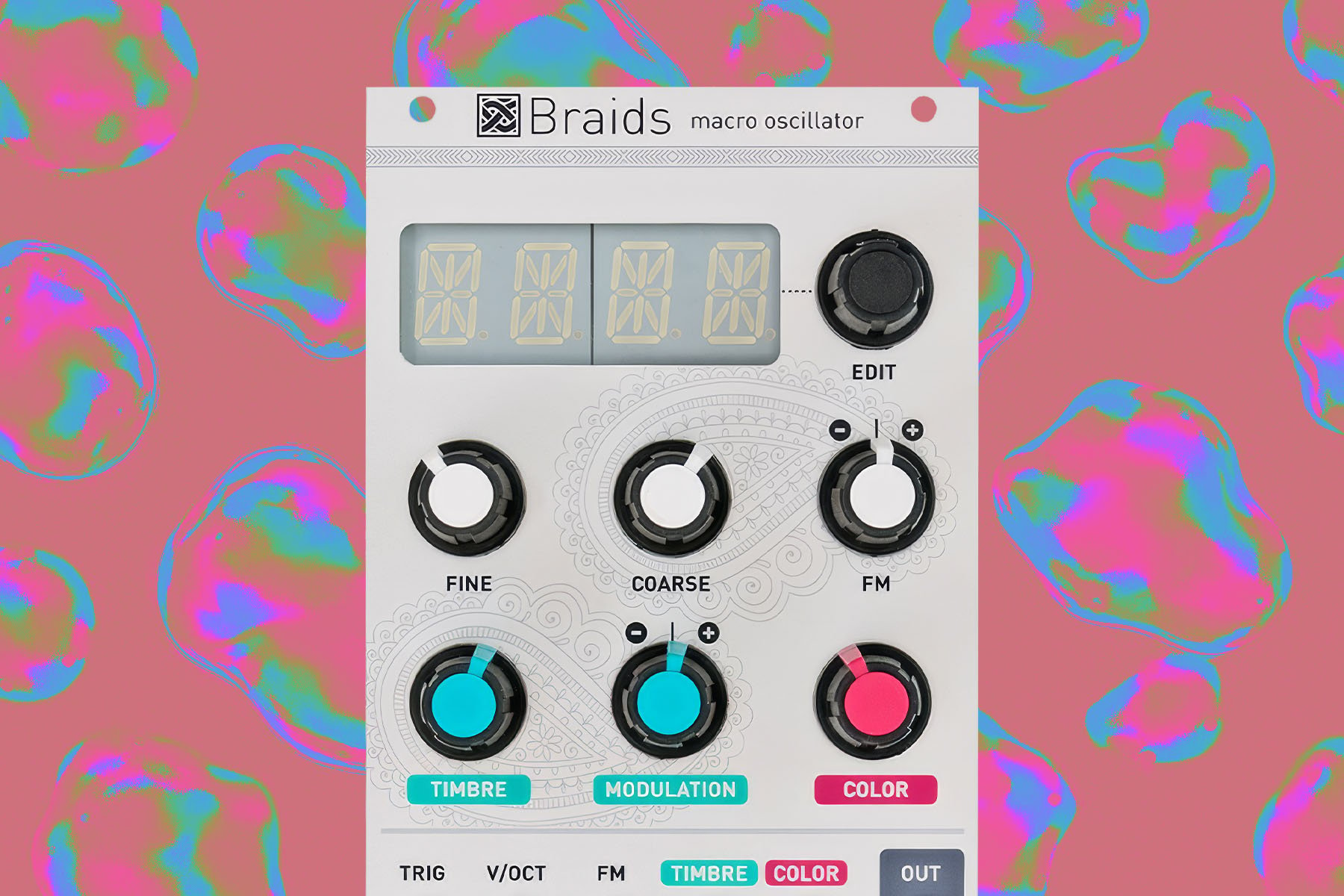

A synthesizer, modular or not, is particularly apt for exploring drones. Running an oscillator output into a filter and applying some subtle modulation to the filter’s frequency cutoff produces one of the classic synth drone sounds. But this is just the beginning. The sonic palette of a synthesizer is vast and ever-changing, offering an unprecedentedly rich tapestry for timbral transformations through techniques like frequency and amplitude modulation, feedback, granular, and wavetable synthesis, coupled with a diverse array of sound processing strategies. Although most synthesizers can be easily adapted for drone music styles, we have seen a surge of instruments fully dedicated to this sonic domain in recent years.

Modern Drone Machines

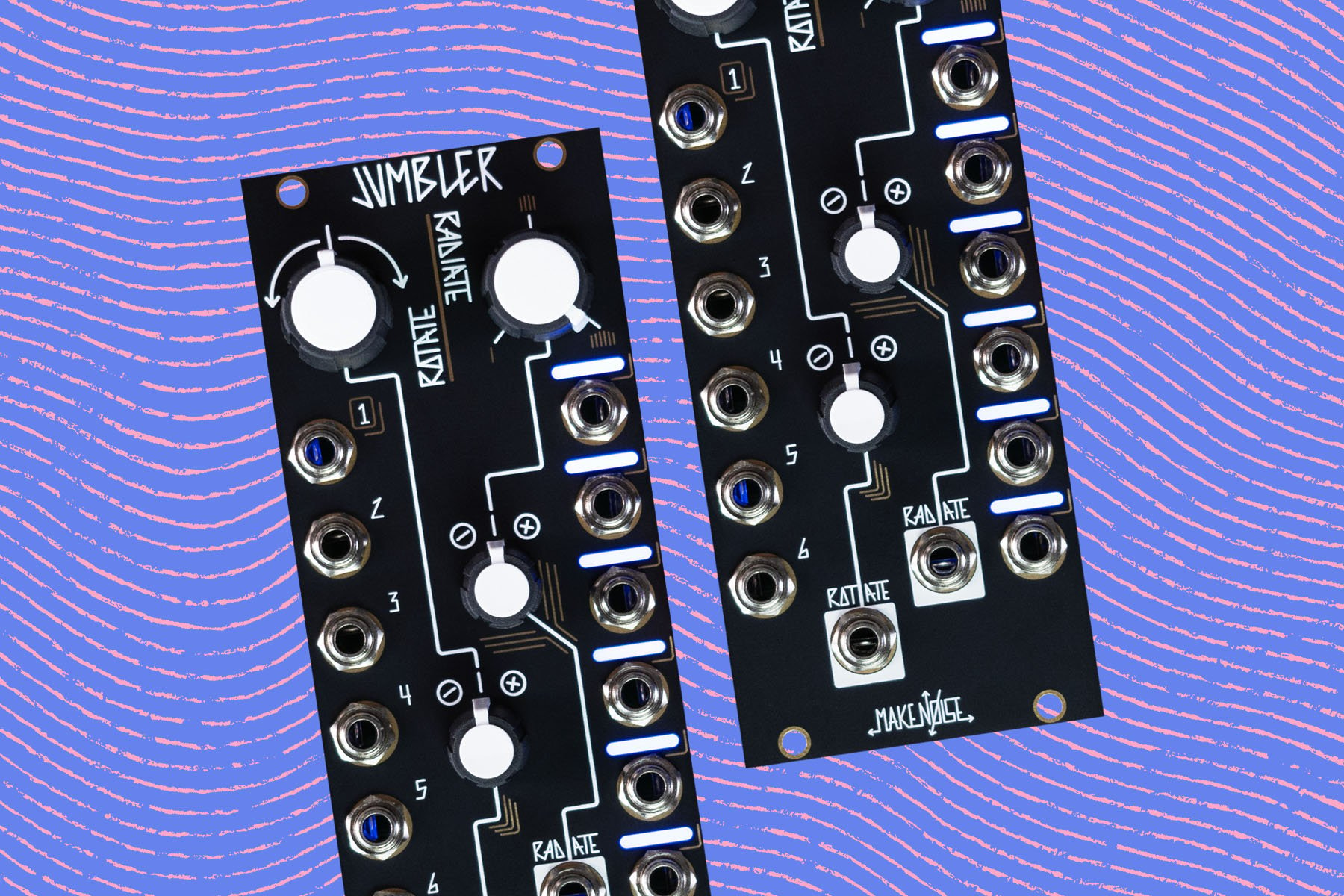

First, let's focus on the Eurorack format. Its revival has brought ambient music to the forefront, with modular synthesis becoming synonymous with these versatile and modifiable music machines. Numerous YouTube synthfluencers have garnered dedicated fanbases by sharing videos of their Eurorack modular synth, producing soothing and subtle textures. The Eurorack format offers a plethora of modules capable of stimulating or augmenting drone creation, from the Verbos Harmonic Oscillator sine bank to the vivid palette of Make Noise Spectraphon, Mimeophon, and Morphagene.

[Above: the drone-laden official product demonstration video for Pipe by Soma Laboratory.]

Some synthesizer manufacturers have designed stand-alone, and semi-modular instruments fully dedicated to drone tones, and perhaps I wouldn’t be too off to start this list with the work of Vlad Kreimer and his outlet Soma Laboratory. Their Lyra-8 has existed for only a few years now, but it gained an iconic status among synth-lovers nearly instantly, praised for its warm, organic, occasionally unruly sound. Soma, in general, has a deep connection to drone music culture, and pretty much all of their instruments, from the audio-activated Pipe to esoteric rhythm machine Pulsar-23, are perfectly capable of trance-inducing sustained tones.

Another designer, whose work easily satisfies our drone desires, is Peter Blasser aka Ciat-Lonbarde. Unique as they are, often encompassing the full spectrum between simple pure tones and chaotic noise, all of Blasser’s designs are perfectly tuned for drone sounds. Cocoquantus, Shnth, oval synths, Tocante solar series, Tetrax and Sidrax organs, and even the rhythm-oriented Plumbutter—each offers a distinct palette of sustained evolving tones, ready to be discovered.

[Above: official product demo for Elta Music's Solar-42, which promises to be an ultimate drone-oriented instrument.]

Another instrument worth mentioning in this discussion is the Solar 42 (previously Solar 50) synthesizer, fathomed by the Latvia-based brand Elta Music. This 8-voice, 42-oscillator ambient music machine is tailored for imaginative slowly developing sonic textures. Moreso, it is not only a synthesizer, but also a capable external sound processor with a built-in Hi-Z input, and swappable effects cartridges.

A few manufacturers keep their drone instruments streamlined, following a general guitar stompbox format. Examples of such include the Drone Thing and Drone King from Electro-Faustus, Maneco Labs Grone, Synamodec Astrogorus, Mattoverse Electronics Double Gate Drone and Drone Tone, as well as a myriad of offerings from the Japanese company JMT Synth, such as NOSC-12, NDS-4, and TVCO-2.

Droning Onward

The symbiotic relationship between drone and music has transcended eras, cultures, and technological advancements, and to this day it remains an essential vehicle for expressing the inexpressible, connecting the seen and the unseen, and evoking the eternal through the transient.

From ancient instruments to modern synthesizers, drone music continues to morph and expand, offering a sonic canvas where the past and the future coalesce into the ever-evolving present. This exploration of drone, a seemingly simplistic sonic phenomenon, unfolds the layers of our profound relationship with sound, revealing the myriad ways it shapes our perceptions, experiences, and expressions of reality.

Drone traverses the realms of the cosmic and the spiritual, and invites us to bridge the external and the internal, to listen, to feel, to contemplate, and to reflect on the intricate tapestry of existence.