I was never any good at physics in school—or any science subject, for that matter. Part of the reason for that was that I simply had zero interest in all of the mathematical mumbo-jumbo that was involved. What difference did understanding calculations have on making music?

Oh, little did I know.

It wasn’t until years later that I discovered the importance of understanding at least some of the basics of concepts like Ohm’s Law—a revelation that came only after I repeatedly blew up my Fender Hot Rod Deluxe by plugging it into a speaker cabinet with an impedance mismatch. That was an expensive lesson to learn!

Now, at this stage in my life I am not going to claim Newtonian-level expertise, but it would be fair to say that there are a few things I’ve picked up along the way on my journey from failed wannabe punk guitarist to mediocre studio musician. One of those is the importance of always having a DI box (or three!) handy. But why? What is a DI box, and why would you need one? Well, to answer that, we’ll probably have to touch on some very basic physics. I can already hear the shrieks of horror, but trust me, it’ll be worth it—and if I can understand it, anybody can.

Types of Signals

Something that probably seems obvious but can take a while to realise is that different devices vary in terms of the strength of their output. For example: as counter-intuitive as it might be given the usual volume that they are played at, you typically won't get as strong a signal from a Gibson SG as you will from a microphone. Without getting too deep into the technical weeds, this is because the output of instruments such as electric guitars and bass is "high impedance"—meaning that if you plug your beloved axe directly into low-impedance equipment (such as the microphone input on a mixer), the results will be disappointing, with the higher frequencies rolled off.

Spend any time at all in guitar player circles and you’ll inevitably hear talk of "tone suck". That’s for good reason...it’s a real thing! There are many factors that play into this, including the length and type of cables you are using, as well as the number of pedals you have on your board—but it can also come down to a simple impedance mis-match between equipment. This type of issue can occur with guitars, or with any other sort of audio equipment.

One of the roles of a DI box is to help solve this.

DI Boxes: What are They? How Do They Work?

DI boxes are also known as "Direct Injection" or "Direct Input" boxes. You will almost never hear anybody refer to them by their Sunday name in the real world, but it provides us with a useful clue as to what they are for. Namely: Directly Inputting.

The main purpose of DI boxes is to convert unbalanced, high-impedance signals (like the sort you might get from a guitar, or even from a synthesizer) into balanced, low-impedance signals (like the sort you'd get from a microphone). Effectively, these magical little things allow you to directly connect up instruments or sound sources which are unbalanced or have a high output impedance, to equipment which expects balanced, low-impedance signals, such as a mixing desk.

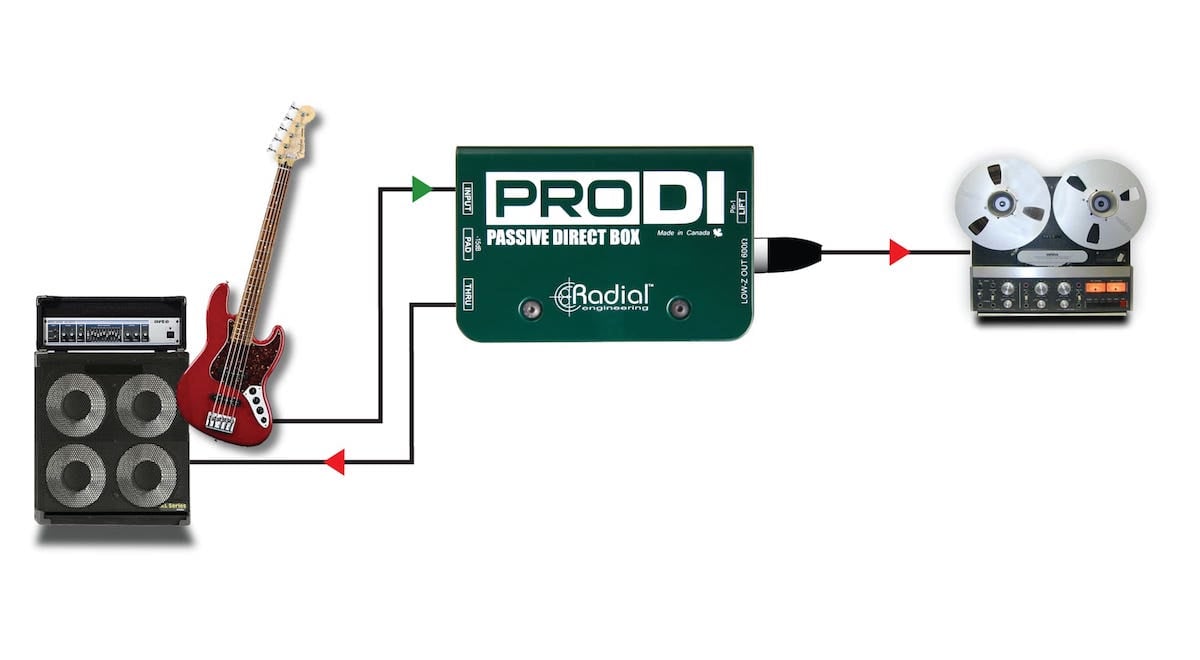

[Above: two common scenarios for using a DI, as illustrated by Radial Engineering. First, a diagram for connecting bass simultaneously to a bass amp/cab and to a PA; second, connecting an acoustic guitar pickup to a PA.]

In addition to that, the nature of low-impedance (i.e. low resistance) balanced signals allows for them to travel much longer distances without signal degradation, and reject both noise and interference much more effectively. As a result, you will often find them in use in live environments, with any instrument or device that needs to be connected directly to the in-house PA system running through a DI first. If you’ve ever tried to plug a keyboard straight into a venue’s console with a 50-foot 1/4" cable, you’ll know why! (Hint: lots and lots of nasty buzzing). As a general rule, if you need an instrument with a 1/4" high-impedance output to travel more than 15–18 feet, you probably ought to instead run the signal through a DI.

DI boxes are usually fairly small, and built like a tank in order to survive being flung into equipment bags, as well as errant kicks from intoxicated guitarists. You do also find professional level rack-mount units such as the ProD8 from Radial Engineering, which can function equally nicely as stage-boxes, or in a permanent studio setup.

The range of different DI boxes available covers every budget and use case, from very affordable devices with simple feature sets such as the ART Zdirect, all the way up to and including impressive beasts such as the Rupert Neve RNDI-8. The most basic of these will often have a 1/4" jack input for the instrument level signal, and an XLR output for the balanced signal. Commonly, they will also include a "ground lift" switch, which can prevent unwanted noise as the result of ground loops.

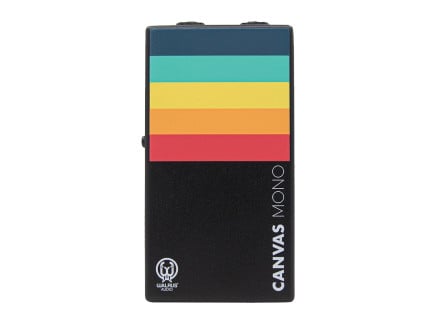

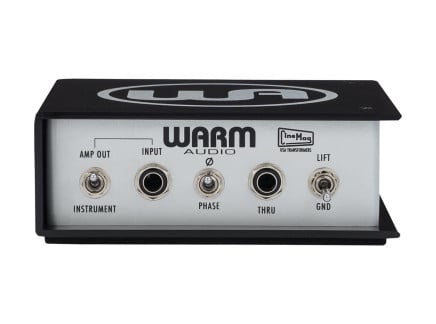

[Above: various images of the Radial Engineering ProDI—in many ways, the prototypical model of how a passive DI should work and what features it should include.]

You can choose between passive units—like the Radial ProDI—or active. Manufacturers like Warm Audio produce both (see the WA-DI-P and WA-DI-A, respectively). The key difference is that active DI boxes will usually include a built-in preamp, which allows them to deal with lower weaker signals. As a result, this means that they require some kind of power source to provide the juice needed to run properly.

Most DI boxes that you come across will be monophonic. However, if you are the kind of maniac that makes chiptune music and performs live with a Game Boy (such as yours truly), then you’ll probably want to preserve all of the fancy panning in your arrangements—and for this kind of scenario you’ll want a stereo DI box, such as the Pro2 from Radial Engineering (possibly one of the most common and well-respected DI boxes altogether). Of course, the same principle would apply if you were to use any kind of stereo sound-source, such as a synthesizer, drum machine, iPad, or groovebox—but those make for far less colorful examples. It’s worth mentioning this specifically because if you happen to play in small venues, then you might find that they don’t have a stereo DI as part of their inventory—and it is often wise to bring your own. I can hear the sound engineers out there scoffing at this possibility—but trust me—it happens all too often. Better safe than sorry. Having a ProD2 in your arsenal is probably a smart bet.

Another common feature found on every DI box worth their salt is some kind of attenuation. This often comes in the form of a single "pad" switch, that reduces the level by a fixed amount. However, you can also find some that offer continuously variable attenuation, such as Radial's Trim-Two—which otherwise is quite similar to the previously mentioned ProD2.

A Brief Introduction to Reamping

Whenever I have recorded with bands in the past, I’ve discovered that I would often want to make tweaks to the guitar sound later on—either to have it better match the song or production style—or simply to have it sit better in the overall mix. This can be a tricky thing to do though, as there is only so much you can adjust the way an instrument sounds, once it’s been run through a specific amp or FX pedal. Sure, you can use a VST to sculpt things, but you’ll never be able to entirely change the character with this method.

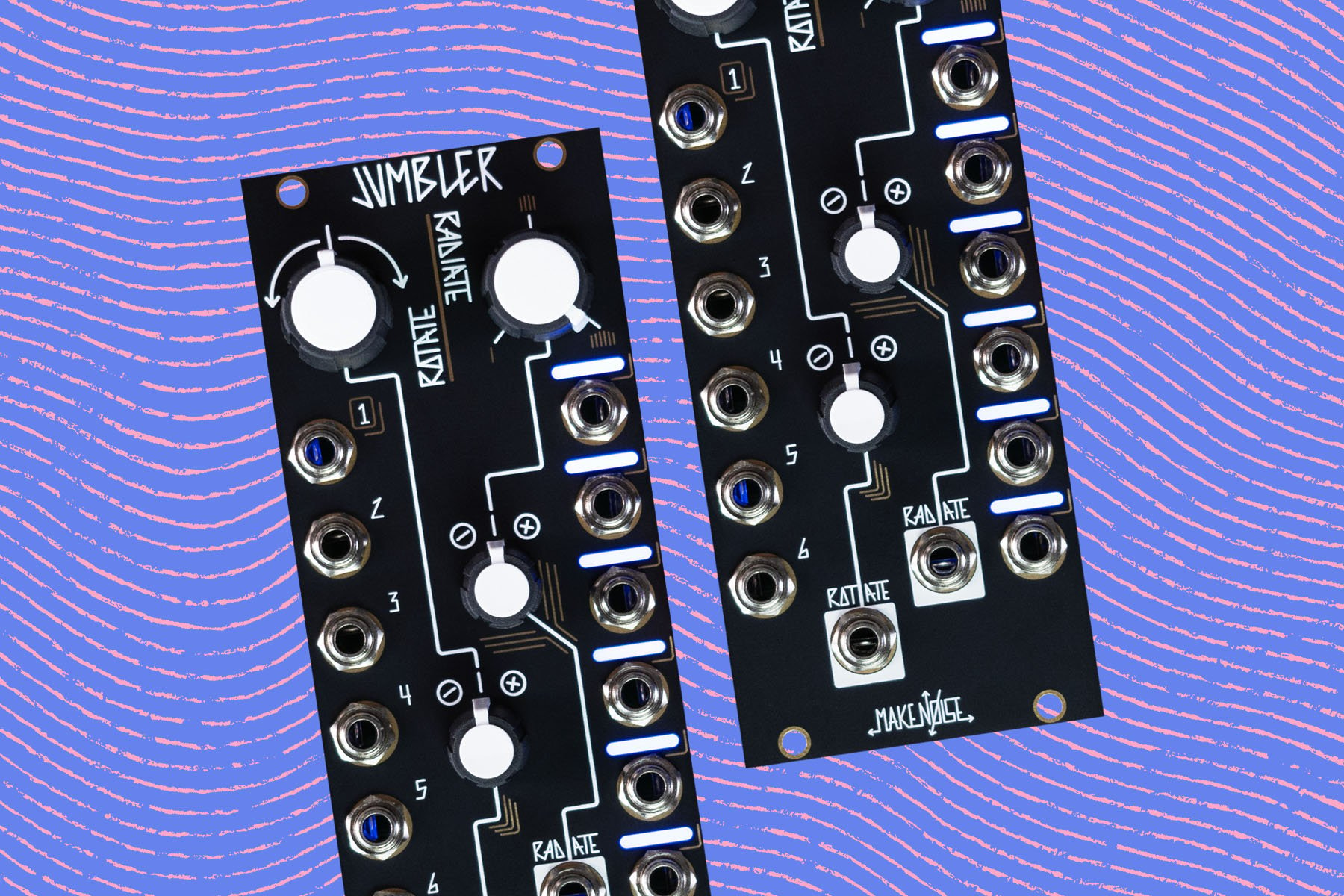

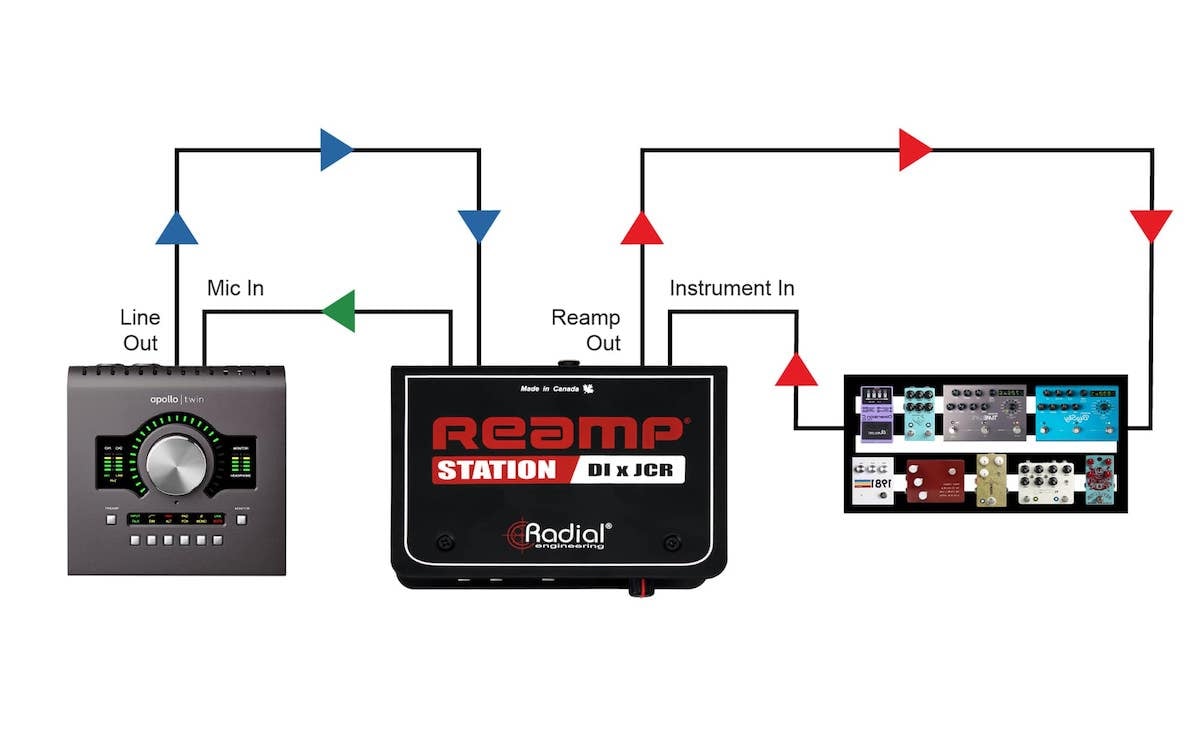

[Above: a common reamping workflow centered on the Radial Engineering Reamp Station—a combination reamp box and DI box.]

One way to avoid this dilemma is to record the instrument completely dry using a DI box initially, then experiment by running the signal back through different combinations of gear. To do so, you will need something like the Walrus Audio Canvas Re-Amp box, which converts balanced studio signals to the unbalanced type required. If you haven’t tried this before, I would recommend it, as it can be a really liberating way to get creative, and provides a lot of flexibility when producing. As a method, it isn’t just limited to those in bands, and once you start to think outside of the box, you’ll realise the potential. For example, isolating the kick drum from your track and running it through an overdriven bass amp, or a synth line through an analog delay pedal. So many possibilities.

If you are a 6 string purist, and don’t love the idea of recording with an entirely dry signal to start with, many DI boxes (including the ART dPDB, as well as the ProD2 that we've mentioned repeatedly) include a pass-through option, where you have an additional "thru" output. This means that you can connect this to your mic’d up Marshall 4x12 and thrash away to your heart’s content, while also recording a completely clean "backup" signal from your DI box. Even if you don’t think you’ll need it, this can be a really good way to go back and fatten up your sound later on with additional processing.

[Editor's note: don't worry—if you want to know more about reamping, you can check out our dedicated article on that very topic.]

Why are DIs So Expensive? A Quick Note on Transformers

Editor's note: you might look at DIs in general and be amazed that something that performs so basic a function can be so expensive. It's true—a high-quality DI can cost a fair bit of money, whereas a simple utility DI that's just meant to get a job done can be relatively affordable. So...what's the difference? And why would anyone pay hundreds of dollars for something that's just meant to alter signal impedance?

The short answer is this: it's all about the transformers (and I don't mean disguised robots hiding in plain sight, though a nice DI is more than meets the eye). Basically, a passive DI is based around an electronic component called a transformer, which does the work in altering the incoming signal's impedance. Transformers themselves can be quite expensive, and generally speaking, the more expensive/better-made a transformer, the better the retention of a sound's character.

In fact, many DIs are prized for the type of transformer they contain—in some cases, the transformer used in a DI can provide pleasant coloration to incoming sounds. For example, it's not uncommon for studios to leave synthesizers, drum machines, or other sound sources permanently connected to a Radial JDI (which uses high-end Jensen transformers) or Rupert Neve Designs RNDI-S (which uses custom transformers). This allows the recording engineer to take advantage of both the character of the direct box and the character of their preamps to add extra color to their instruments' sounds.

Let's Be Direct

DI boxes are essential bits of equipment that should be in the tool kit of every musician or producer. They are affordable enough that it is often wise to have your own on-hand for playing live, particularly if you play the toilet circuit, or have an unusual or particularly complex setup (such as giving multiple individual outputs from your DAW to the front-of-house engineer).

They are the connecting bits of pipe which let all of your different devices talk to each other, and can allow for some pretty interesting experimentation, should you be so inclined.

Check out Perfect Circuit's full selection of direct boxes here!