It’s ironic that what diverted much of ALM/Busy Circuits’ Matthew Allum’s attention while studying at university and would derail his studies—music, specifically the enthralling scene of '90s Bristol, England—would end up as a throughline in his life, serving him so well later on. After leaving music behind to focus on his career, Allum worked for various corporations until starting his own technology company. He would come back to music through a renewed interest in modular synths, eventually forming ALM/Busy Circuits.

Celebrating their 10th year in business April of 2023, with a pop-up shop in London, ALM/Busy Circuits has made a name for itself with innovative, striking, and idiosyncratically-named modules such as Dinky’s Taiko, Akemie’s Castle, Sid Guts Deluxe, and of course, Pamela’s New Workout.

Allum has done well by noticing what is around him, where the openings are, and what people respond to, turning ALM/Busy Circuits into a recognizable force in the modular landscape. It’s a perfect illustration of what you pay attention to is what ultimately defines you.

Sometimes something that derails your life may in fact be one of the things that makes it fulfilling. Allum is now immersed in a life full of music, sharing it with the synth community, friends, and family—his kids enjoying some of the same songs and artists that made him miss his studies in Bristol.

An Interview with ALM/Busy Circuits

Waveform: ALM / Busy Circuits...are they two different businesses? What’s the deal with the name?

Matthew Allum: It was a kind of nod to EMS, ARP, that kind of thing, and I wanted a simple name that I wouldn't end up hating, and I wanted to go with ALM, but there are a lot of other ALMs out there, like big, massive companies called ALM. So I tacked on the Busy Circuits because I liked the words “busy circuits,” I liked the two names together. I figured I would eventually drop one or the other, but then we ended up sticking with them because I also liked the kind of the confusion it causes. Someone will say, “Are they two separate things?”

I like the Busy Circuits part, too. It sounds very hi-tech in an atomic, nostalgic sort of way, like old operating systems or phone lines being jammed…What does the ALM part mean?

It doesn't really stand for anything, I just like the letters together and had been doodling the logo before we had the name and thought it looked good. It’s visually the way the letters go together that I like.

What about module names, like Pamela’s Workout and Dinky’sTaiko? Who are all of these people that the modules are named after? Is there a Pamela?

Well, that's a trade secret.

Is it really?

All the names…they're just silly sort of in-jokes. We keep them a mystery. I love the artwork on Tamiya remote control cars and how they were always named “somebody something,” like “Vanessa's Lunchbox”…that's where the idea came from.

You said you had been sketching the logo before the company started. ALM’s been around now for over ten years, how long had you been thinking about starting a modular company before that?

It wasn’t like I went out and started a company, it was more that I’d always been into music and music technology since I was a teenager. Through university, I was making music all the time and I loved it.

Where did you go to university? Were you studying music and technology there?

I was doing physics at Bristol. I was the first person in my family to go to university, and Bristol was a very cool city with good music and everything. I wanted to stay there but things didn't go too well for me. I enjoyed myself a bit too much and had run out of money so I had to go back home to my parents who were just outside London. I’d majorly screwed up. I thought I'd just about scraped through, but I didn’t, I got a third class honors, a “Richard the Third,” we used to call it. I remember seeing my results and suddenly thinking I'd let everyone down, all my family. My parents had to pay for me to go through university and I felt really bad. I thought, “I've got to sort myself out. I’ve got to leave music, get a job and work hard.” So I got away from music. I kept some of my synths, but I sold most of them and got a job.

You had to gain the trust and support of your parents back, to redeem yourself….

It’s been quite a long arc (laughs). This was like the mid-90s, so it was around the beginning of the internet. At university we knew how to make web pages and that kind of thing, we knew a bit of technology. I'd always been interested in computers, and I could use Cubase and eventually, I got a job at a design company that did CD-ROMs. The company wanted to get into internet stuff, and they used a software called (Adobe) Director, and because I could use Cubase I got the job.

Was this in London?

No. I wanted to move into London but I didn't have the money so I ended up working in Slough Trading Estate. I just worked and worked and worked, and then within a couple of years I moved to London and did well with different companies in software and the internet, and that culminated in me running my own company.

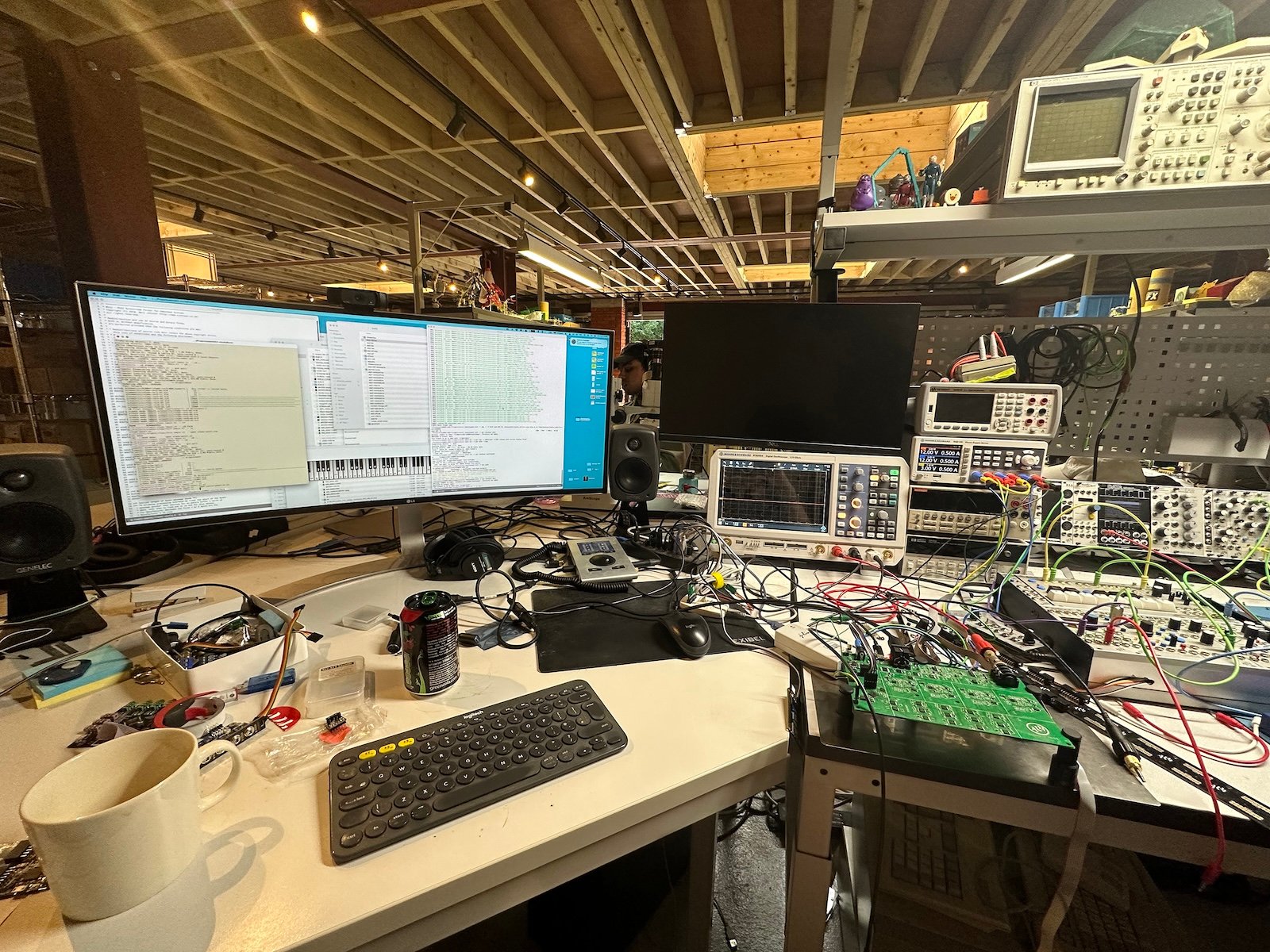

[Above: Matthew Allum's workspace at ALM/Busy Circuits headquarters]

How long was it from getting that first job in Slough to running your own company?

I got my first job around ‘95 and I started my company in 2002. It seems like a long time thinking back now. We were doing software, embedded Linux, really early on before anyone else. People thought it was bonkers that we were running Linux on these Compaq iPaqs, which was way before the iPhone and all that sort of stuff. It was when color screens came out and you could run a full OS on a handheld device, but people at the time thought it was completely stupid, like, “Why would you do that?” For whatever reason, it completely gripped me. Then I started this company and we did a lot of work for Nokia R&D. My company grew to thirty people and we were doing work for all sorts of people. It was very successful and we ended up getting acquired, so it all ended quite nicely. It was pretty cool.

At this point, when your company got bought did your parents finally give you the thumbs up? Did you feel that you’d redeemed yourself since college?

They never held it against me, it was more that I had now validated myself. I had been successful, but I was working sixteen-hour days when I was running the company. It was just constant firefighting and it was nonstop, relentless with no holidays…nothing. I was a mess.

That must have been nice to get acquired then, less stress.

Yeah, but the whole process of selling the company was very stressful in terms of dealing with lawyers and that kind of thing, and another stressful thing was that one minute you're the boss of a thirty person company and the next minute you're working for a company that's exponentially larger than that, and you've suddenly got bosses and you're in a very different environment that you don't necessarily understand, and the rules are very different.

Did you have to stay on with the company afterward?

For a couple of years. I’d thought that I would stay longer, and it started off okay, but it just didn't work, I didn’t enjoy it at all. I’d had enough of tech and the whole world of it. I was really disillusioned. I saw where it ended up.

What were you disillusioned by?

I didn't like the way that we'd put so much hard work into this stuff and it was very throw away, like it would disappear and then be gone forever.

That it’s all so disposable?

Disposable, exactly. I wanted the company to succeed and had dreamed of it being acquired and being successful, but I thought it would take a lot longer, like twenty years, and it happened much quicker, over six months. When the iPhone got announced, everything just went bonkers for us because we had similar technology. All of the sudden, everyone needed it. It was a very specific technology that we did, and this was around 2008, just before the financial crash. I was at my limits in terms of needing a break, and I had taken the tech as far as it could go so it was good from that perspective. I took some time off and thought, “I'm gonna be a carpenter.” I just wanted to do something completely different…

I get it. Building something with your hands. There’s something about the work that seems deeply satisfying. How did your experience as a carpenter go?

I discovered that I was absolutely useless at that. (laughs) I didn't have the ability to measure by eye... I enjoyed it for a bit, but it definitely wasn't where my skills were.

That must have been hard, figuring out what was next.

I didn't know what to do. I did a little bit of consulting and bits and pieces of things. I’d always loved music and music technology, and the (Teenage Engineering) OP1 had just been announced and I was quite excited about it, and then I saw that you could get these modular systems. When I was younger that kind of thing was unimaginable, so I got a Doepfer system and I loved it. I still had my SH-101 from years ago, and my 606 and I started hooking it all up and it was so much fun. I looked at the Doepfer modules and thought, “I could do this.” I had electronics knowledge from when I was a kid, a physics degree, and I'd messed around with Arduinos and stuff a little bit. I wanted to sync my 606 with this weird MFB drum machine that had like a X12 clock, and I wanted to sync it with a modular as well, and there was nothing that would really do that. So this was kind of the first version of Pam (Pamela’s Workout), just this simple thing that synced them together.

I started working on that, but the main thing I was working on was the ASQ1, an SH-101 style sequencer. It was going was originally going to be a standalone sequencer, a separate thing and not a module, and it was technically challenging. I had a prototype of that and had a prototype of the Pam, and then I found the little screens that the original Pam used and I got the UI working nicely and I was like, “Oh, this is actually pretty cool.”

When I first got Pamela’s New Workout, I was like, “Why didn't I get this earlier?” It really brought my system together.

The original Pam was just clocks and then the second Pam was technically much better. It was what I wanted the original Pamela to do but just didn't have the capability through the hardware or the software. We updated almost too much over time—there's no space left on it for anything else—which makes it really difficult to debug.

[Above: image from ALM/Busy Circuits 10th anniversary popup event in 2023.]

Did you know when you were working on Pam’s that it would resonate with people, would really fill a need?

I still thought the ASQ sequencer was kind of the main thing, but then I went to one of the first Brighton Modular Meets and I had both of them there to show people what I was working on, and I was like, “Look at this SH-101 sequencer thing I made!” And everyone was like, “What's this clock thing? What’s this doing?” Nobody was that interested in the ASQ, everybody was interested in what would become the Pam, so I thought that I should work on that because it seemed like the more interesting thing, and I’d go back to the SH-101 idea later.

So I started working on Pam, and I found a place locally that would manufacture them for me. I figured out I could do a run of fifty, and as long as I sold half of them, I’d cover my costs. I got them made and I contacted Analog Haven and Postmodular and I said, “I’ve made this module, will you stock it?” And they were like, “No.” (laughs) So I announced it on Mod Wiggler and I put it up there and the fifty sold in a week and it just grew from there. The first few years it was still a hobby, a nice kind of sideline, but it wasn't really making enough money to be a business. Gradually, it grew until it was a business and now we've got a small office in Chicago and one in South London.

Are you still the only designer for all the modules?

I do the bulk of it. There are eight of us now, and we all do a bit of everything. It’s a nice team.

As ALM grew and you started adding employees, did you seek out people for specific positions/skills or was it more organic?

It was definitely more organic. The company's always been run quite organically and with a drive to grow, but definitely at a pace that's comfortable, rather than any sort of aggressive growth. I don't think we've ever advertised for a role for hiring. That's been more organic as well, where people have done bits of freelance work for us and then that's grown into working full-time. Also, we've had some really good interns, which has worked really well. It's still very small.

There is a certain type of mystique to ALM/Busy Circuits. Your whole aesthetic is unique with the names, and even the gray panels. Nobody really does gray panels, which look really sharp, especially in the System Coupe. Do you come up with the aesthetic for the company as well as the faceplate designs, or do you have somebody that does that for you?

No, I do it all myself, though nowadays there’s input from other people within the company, but I think pretty much all of them have been done by me. It's funny because when I did the original Pam I came up with a plan in terms of what knobs I was going to use, what sort of styles of switches I was going to use—a kind of rule book—and I've stuck to that, and am still sticking to it, but I would really like to break out of the rules and do something that looks very different, but within the rule book. We've had a lot of fun playing with things like the Coupe, the colors and that kind of thing. It's fun to play within the limitations and also sticking to a set of rules means they all look great together and it can be quite unique. I like the way they all have their own kind of character, their own kind of little soul, which is what the names give them. Also the choice of fonts and whatnot I find fun. It's fun being able to do things that are incredibly technical but then at the same time visually very fun.

[Above: video demo of the System Coupe—the first pre-configured full ALM/Busy Circuits modular system.]

When you came out with the System Coupe you had a Speed Racer type of ad for it by a Chilean artist José Salot (PEPEGR∆PHIX), and you mentioned the Tamiya remote control cars that you were into. Are you big into cars? Do you collect them or anything like that?

The Coupe is car based because it’s quite difficult to come up with a name for a system and it really fits with the logos being like racing logos and that kind of thing. It seemed like a quite fun concept for it. When I was in my early 20s classic cars were still quite affordable and I tried to collect various ones, but it was a disaster. I had a Karmann Ghia where the engine blew up, a '66 Mustang that died on me, and a (Toyota Land Cruiser) FJ 40—which was my favorite—and the engine blew up on that as well.

Wow. So how many cars have you blown the engines up on?

Only two, but it was more bad luck than anything. The Karmann Ghia was beautiful, this champagne silver color and it was so nice to drive, but it was air-cooled and since I was sitting in traffic a lot I thought I’d get a bigger fan, because in Mexico they drove Beetles with bigger fans. So I got a bigger fan for it, but what I didn't notice was that there was a paper towel stuffed down the side of the battery that had been there for years and the big fan sucked that into the engine and that was that.

That is bad luck.

And then the FJ died. That was the worst because I'd literally had that a week. I drove it out on a cold morning and because it had come from Portugal or somewhere hot it didn't have any antifreeze in it. All of a sudden smoke started pouring out of it and it cracked the block. Those things are meant to go for years, they're meant to be indestructible. The Mustang was alright, but when I had kids it just got left in the garage. Occasionally I’ll see a nice car and go, “Oh, I could get one of them,” and my wife goes, “No way. No more. No more classic cars.”

She knows. How many kids do you have?

I have two daughters.

What do they think about ALM/Busy Circuits?

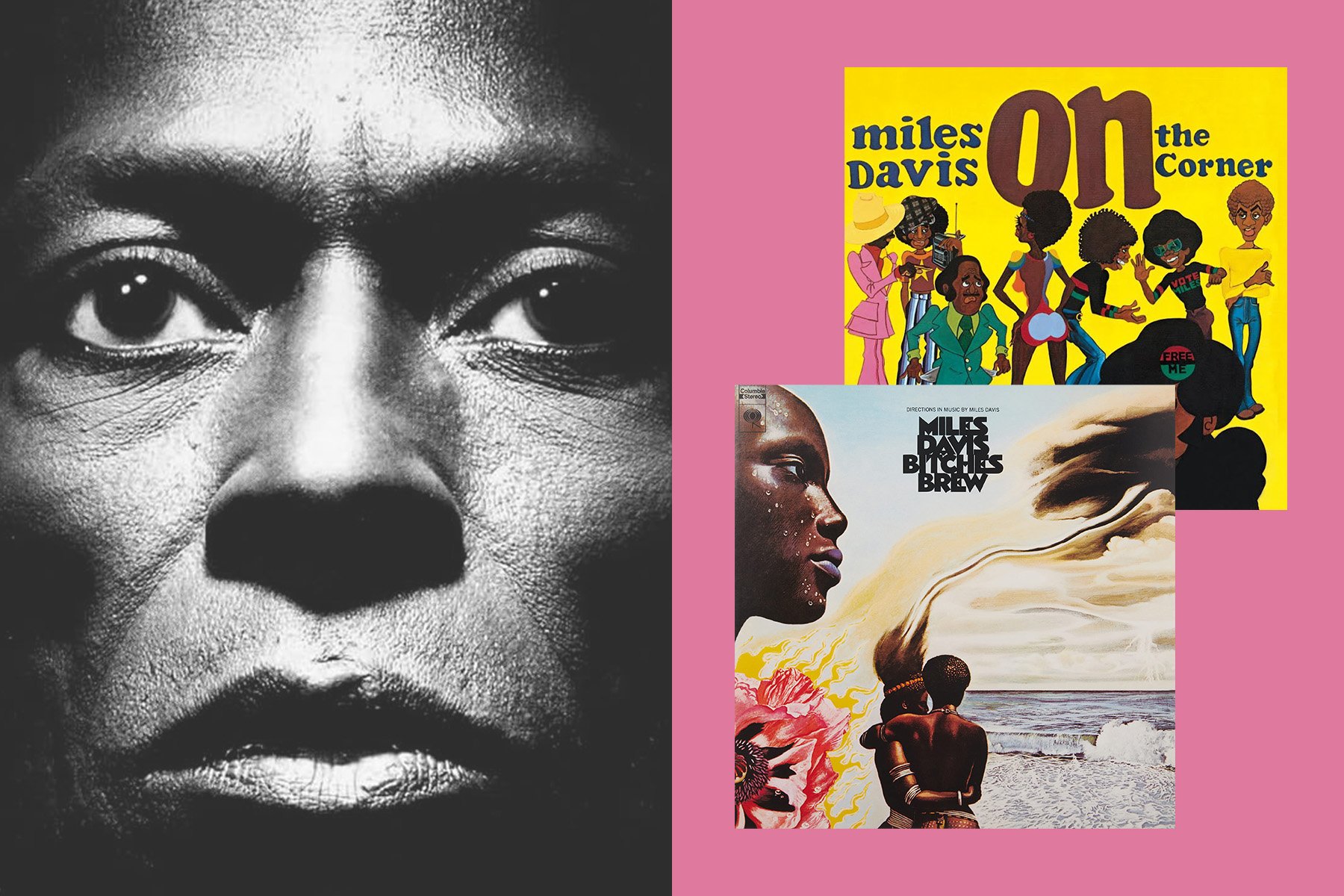

They like it, they think it's cool. They call it pots and pans music. (laughs) My older daughter is into guitars and started getting into effects pedals. It's funny because sometimes I hear her listening to music that I grew up liking. I find that really strange.

Like what music?

When she was younger, I would play her Aphex Twin tracks that I liked, so she's grown up liking them, and she plays Grand Theft Auto—though she shouldn’t—and the music on that she puts into Spotify, and so then other stuff comes up. I came into her room once and she was listening to this really old, UK techno and I'm like, “This is B12.” And she’s like, “Yeah, I really like this one.” (laughs) Other things, like when you have a secret song that you wouldn't tell anyone you like, like pop songs, but she listens to them. There's this Lily Allen song that I really like, but I would never admit it to anyone, and she keeps listening to it. I think that's really weird.

It’s the algorithm. What's your process for designing something?

ALM vending machine at ALM's 10th anniversary popup shop; 2023.

ALM vending machine at ALM's 10th anniversary popup shop; 2023.

Pretty much every module has been me going to patch something and getting frustrated and then I spend the next six months or a year developing something. When I was younger and making music it was all about the sampler, but it was a lot more basic then. It was working with the limitations, not that much sample time and quickly messing with sounds and making new sounds. I missed that from Eurorack and I'd been thinking about a sampler, thinking about how I could do it. I wanted something that had the kind of spirit of a rackmount sampler—it wasn't trying to be a really complicated type where you’re carefully editing—I wanted something more immediate and fun, and that’s how the Squid came about. I took some of the ideas from how Pam worked but made it a bit more immediate.

It’s kind of weird with Eurorack because people don't like menu diving—or they think they don't like menu diving—but in moderation, it's actually pretty useful. I see a lot of modules where people go the opposite way and avoid having a menu, they make it more complicated by having hundreds of buttons, a bajillion different things. It’s almost more confusing. I try and design so you can get 80% of the module’s functionality without looking at the manual. It’ll be stuff that hopefully you’ll remember easily, where you won't need to refer to a cheat sheet, that you can get the core of it, but then if you want to go further and dip in, it will do a lot more. You get to a point now, especially with the Squid, where the features get so dense, that it might be that you do need a cheat sheet, but I’m desperately trying to avoid that. It's more specific kind of features, the really advanced stuff, not the core functionality, that maybe 1–5% of your user base will use, and I don't think that's too bad if that's kind of hidden away, but 80 or 90% of the functionality I want immediately. I want it so you can pick the thing up and within five minutes, you're having fun. I want to make people smile and make noises they wouldn't expect, and with the names, there's the humor in there where it’s not being taken too seriously. One of the great things about Eurorack is, it’s a little bit of the wild west in terms of the standards being all a bit loose and whatnot. It’s kind of annoying in some ways, but then you are really free to do whatever you want. It allows for all of this amazing creativity and the range of modules you can get, the things that they'll do, and the designs…I can't really think of another kind of thing that’s like it.

Do you feel that it’s an accessibility issue? It’s easier to find information, order parts, get things made; it’s definitely become more democratized now. You can make a DIY system that as little as ten years ago would have been nearly unthinkable.

It’s become so much easier to manufacture things, especially electronics in the last sort of ten, twenty years; it’s more like running a record label compared to running a technology company. It’s not impossible to do small runs, and we’ve done odd modules, where there's only a handful that exist, but it's feasible to do it. You might not make much, but you won't lose money, you can cover yourself.

I’ve never thought about the parallels between the modular scene and a record label, but you're right, it is like a small record label where you can do small numbers, and really take chances, follow your passion, and find your fanbase.

Yeah, definitely, though as we've taken on employees and responsibilities, it becomes slightly tougher. There's got to be a bit more of a plan to it, but we can still do that. There are definitely some fun, interesting projects in the works that are sort of bubbling away.

[Above: the final version of the ALM/Busy Circuits ASQ-1 Sequencer]

Was the ASQ-1 something like that, something that'd been in the works for a while, in the back of your mind, that finally bubbled up? Why did it take so long to release it?

I don't know what happened with it, I just got sidetracked with other stuff and it got shelved because it was complicated to build in terms of it needed a case as a stand-alone thing. I had it at the first Superbooth, and it got some interest, but the software then was quite buggy and I wasn't that happy with it. I wasn't quite sure how to make it strong enough and there were some issues with some of the parts , but then Zoey (Guyette, ALM Chicago office) came over to visit our office in the UK and he found a box of prototypes and was like, “What's this? You’ve got to finish this.” I was like, “I don't know.” And then Jack (Adams) Mumdance came into the office and saw it and said, “What's this?! You’ve got to do this.” So I was like, “Well, maybe.”

It's similar to what your experience was with Pamela's when it first came out. You noticed what people paid attention to, where the interest was, and you went with it. It almost just seems like a timing thing, where back when the initial Pam’s was released people were more drawn to something with dense, compact functionality, but now a larger, more unique looking module that’s maybe more performative and less programmy draws the attention.

Yeah, definitely. It actually uses the same processor that's in the Pam’s. I like the way that it isn't trying to be complicated, isn't trying to do anything. It's not cramped, it's very nice to use, to plug away at the keys. I like the sort of 101 style sequencing, where you don't really know what you're doing, but always comes out good, there’s always a nice surprise to it. I added a little bit more functionality so you can save and load efficiently, so that you can use it more in a live context, and I’ve added some extra things here and there, like overdub. The thing with the 101 was that I always had to count what I was putting in, so it would be like sixteen steps added…(ASQ-1) shows you the length and where you’re at, and then with the extra space, we've got the four trigger pan channels, which is like a regular drum machine, as it uses the eight white buttons to represent eight steps and kind of cycles through them.

With the Quaid Megaslope (reviewed in Waveform Issue #3), we always wanted a quantizer for that. You can kind of run things through Pam as a quantizer but it's not ideal, and Pam's doesn’t have super high resolution on the CV outs, whilst the ASQ-1 is 16 bits. It’s a nice resolution for a quantizer and also it's very easy to program in the scales you want very quickly, and you can load and save them as well. ASQ-1 fits well without other stuff. I was thinking people would be a bit like, “That doesn't do much. Where's the screen?” But people seem to love it.

I think the timing was right for those type of keys and playability. Mechanical keyboards are big now with gamers and coders. Even electric typewriters are making a comeback. Was it hard sourcing they keys for this?

No, surprisingly not. We found really nice key mechanisms, which I didn't have in the original, and that made it a lot nicer. They make a really nice sound and the caps are nice as well with a little round LED, which just fits with everything. They come from the company that supplies our knobs and I think it was more fluke than anything because I was thinking that there must be someone doing the 909 style with the square cutout (for the LED), but they had these with a round cut. It was perfect. Sometimes modules just kind of come together, and other times they’re like…Akemie’s Castle was hell developing. That had so many problems.

What kind of problems did you have with that?

Just weird problems. It just wouldn't hold pitch. I had all these funny problems where it would do these little wavers in pitch, this minor kind of drift and it turned out the reason why had to do with how the components were laid out on the board. It was just so unlucky. I was sort of banging my head against a brick wall for six months.

That's a large module. Did you have to reroute the whole thing?

No, it was literally—if I remember rightly—a trace going under a high impedance input. 99% of the time the things that go wrong are that you've put the power the wrong way around, or you've just miswired something. It’s not some mystical electrical, electronics issue, it's something silly and obvious and stupid. But then occasionally it is this electronic weird voodoo stuff. It was driving me mad because everything else worked and I Ioved the way it sounded. I was excited, because it was a big module and I knew there was nothing else like it, and everyone that was playing it was having so much fun with it. Even now, it's probably still my favorite module. I'll play with it and still find sounds in it. It's endless the sounds that come out, and they're unusual.

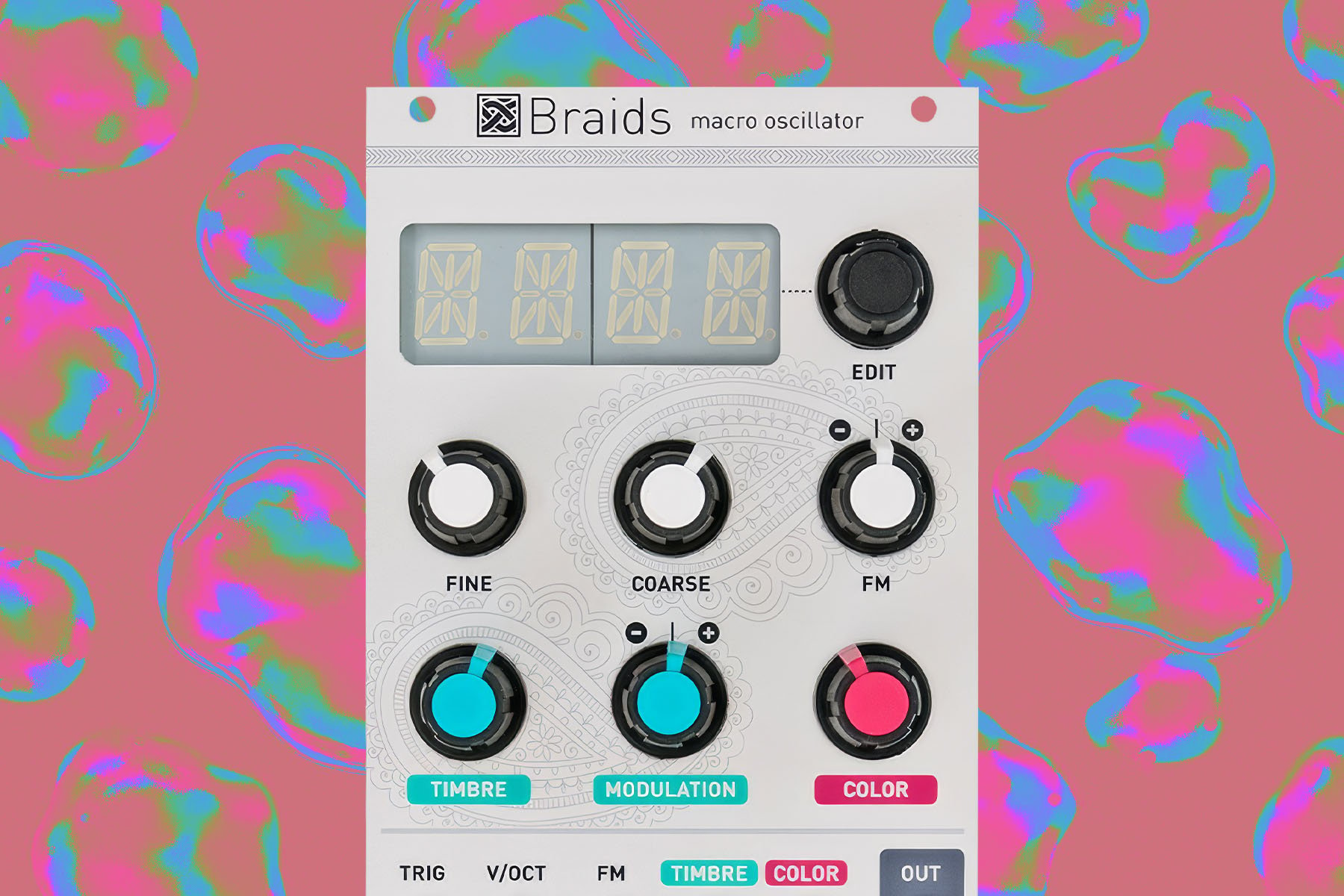

It’s interesting that you used “new-old-stock” Yamaha ICs for Akemie’s Castle. Like they didn’t take their FM technology in a way that you thought it could go, so you took it into your own hands.

I find it fascinating why Yamaha never released something with knobs, because it's just so much more fun to explore the sounds like that. I met John Chowning (Ed. - He developed FM synthesis and licensed it to Yamaha for use in the DX7) at Knobcon. I had the Akemie’s Castle with me and I wanted to get him to sign the back of it, and I did chat with him a bit, but I didn't bring the hex tool, so I was desperately running around looking for one, but because it was a European size nobody had one! That was quite funny.

When you think of the Yamaha DX7, it's somewhat exhausting to think about programming it, but it obviously didn’t seem to matter in terms of its popularity.

I guess they were selling so many of them, and it was almost a luxury to have the screen and those kind of controls because it was very modern back then. Now you get an iPad and you've got this amazing control surface, but it's so commodified— everyone has one in their pocket so that now that kind of luxury is the knobs. It’s kind of flipped around.

When I think about what the word luxury means, it’s almost like luxury versus technology. Like the light bulb? That’s technology. The candle. That's the luxury now. Light bulbs are cheap, but a beeswax candle is not.

Yeah, and with the modules, the electronics are cheap compared to the controls. The same with all the other components and even getting them made…. The cost is in the electromechanical stuff and the jacks, and then getting them all soldered and that kind of thing.

It's like 80% of the module is done for 20% of the cost. Do you manufacture ALM modules in-house?

No, we use contract manufacturers in the UK. We do all of the R&D and the design and everything and on the lower run stuff, we'll do the final assembly in-house and some of the testing, but we don't have our own pick-and-place machines or anything like that. In the UK there are very good contract manufacturers, where almost all the work they do is small runs for MOD (manufacturing on demand) or very specific industrial equipment, so if you come to them with something interesting they seem quite up for doing it.

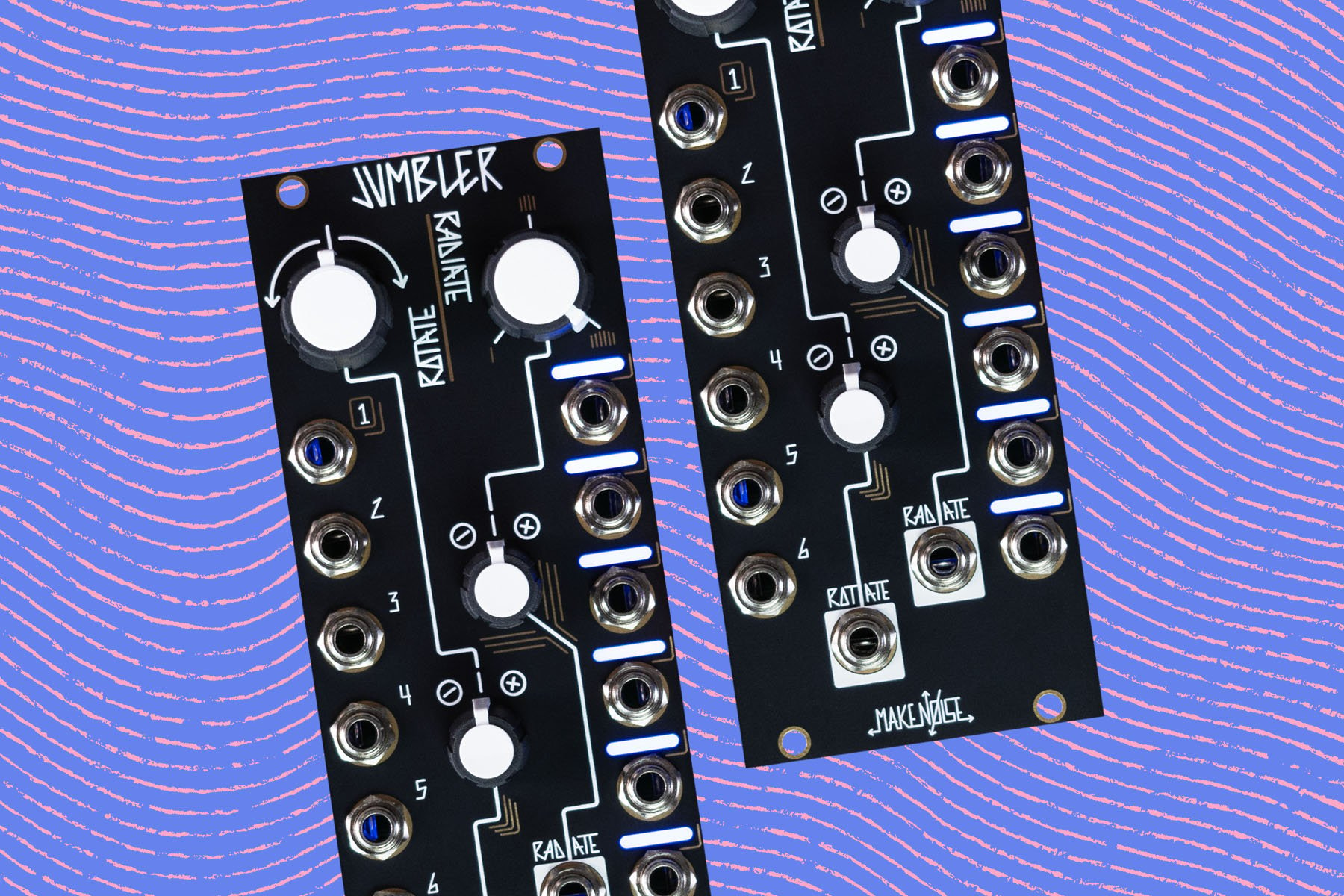

We talked to Morgan from Worng and he was talking about the collaboration you guys did together on the Jumble Henge, and that he couldn't believe this bigger company like ALM was interested in working with him.

It’s funny because I was thinking, “Oh, he won’t want to work with us!” I love the Worng stuff, and I had chatted to Morgan before and we exchanged emails and there’s mutual respect. I love the Soundstage, but I wanted a smaller version, so I said, “What do you think of doing an 8HP version together?” It went really smoothly, he was great to work with. He’s a lovely guy.

He was talking about people working together and collaborating and it’s pretty cool that throughout the history of synths there’s been an undercurrent of people from other companies working together, that it's not this cutthroat thing like in a lot of other industries.

We’ve always been pretty careful not to step on people's toes. We're definitely not trying to make products that directly compete with others. There's always going to be some overlap, especially on bread-and-butter-type modules, but we try and add our own spin. We’re not aggressively trying to compete or outprice anyone or anything like that. We could have gone off and made our own Soundstage but it was cooler to work with Morgan. Although the brands are different, I guess they're kind of similar in a way.

Was that your first collaboration?

We've done fun collaborations before. We did a Haswell version of the Dinky’s Taiko with Russell Haswell, who's a noise artist. He’s a real character and a lovely guy, and has been a real cheerleader and friend since I started ALM. He'll make sounds out of our modules and I haven't a clue how he's doing it. He liked the Dinky’s, but he had to really process it to get it sounding like his kind of sound, and I mentioned that we could put an alternate set of waveforms in. He was like, “Can I draw them?”, and so we did that, and that was a really fun project. When he plays, he’ll always want a really clean system because he's getting a physical effect, he's pushing it, taking that further and further. I find that really interesting. You don’t just listen to music, you're feeling it.

Thanks to Waveform Magazine

Waveform is a quarterly print magazine about sound synthesis and those who inhabit that world. Check out Waveform on our site, or head to their own website to subscribe, or to grab some swag, DIY projects, and more!