Scott Jaeger is a name that is undoubtedly familiar to any Eurorack and modular synthesis aficionado. He was among the first to start expanding the Eurorack universe beyond the Doepfer A-100 system with his original forward-thinking, and unapologetically digital designs. His modules are known for their punch-in-the-face-like sonic quality with an incredible amount of character, and a very original workflow. They can be easily spotted from afar bearing the unmistakable orange knobs-on-silver-panels aesthetics. Shortly after Scott started producing his own modules, the name "The Harvestman" was on the lips of every Eurorack user. A few years ago the company was turned into Industrial Music Electronics, thus ultimately emphasizing the sonic character of Scott’s designs.

Excited about the release of Bionic Lester Mk3, we reached out to Scott, and he was kind enough to talk to us about his ideas, influences, as well as past, present, and future plans. We love what Scott has to say, and we sincerely hope that you will enjoy reading this interview as much as we did.

Circuit-bent Casio SK1 (Image taken from Reed Ghazala's Circuit-Bending: Build Your Own Alien Instruments book)

Circuit-bent Casio SK1 (Image taken from Reed Ghazala's Circuit-Bending: Build Your Own Alien Instruments book)

Background

Perfect Circuit: Hi Scott. Thanks for talking to us. I’m sure many of our readers are very familiar with your work, but could you describe your earliest encounters with music and electronics? How did it all start for you and who/what influenced you at the time?

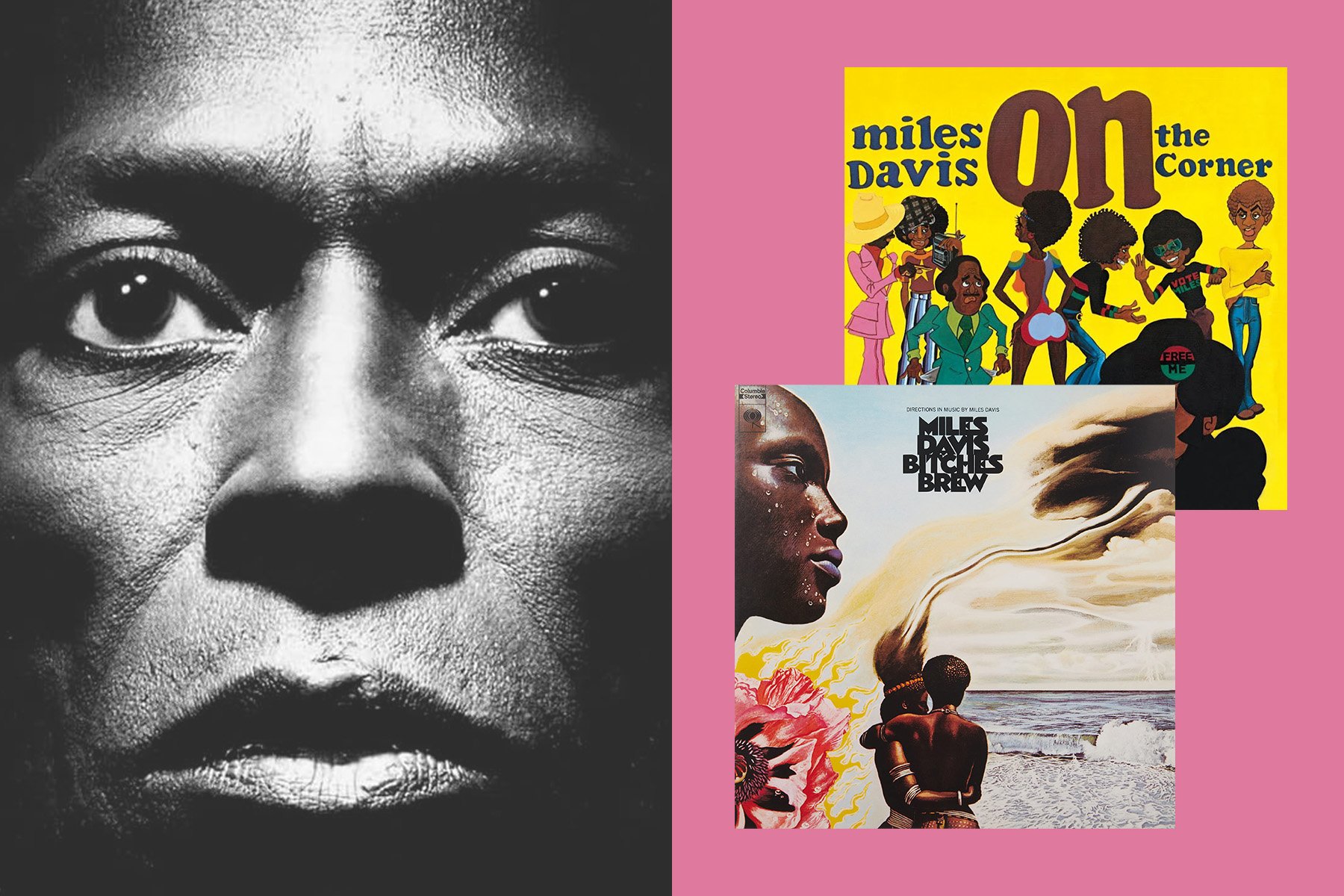

Scott Jaeger: My family was supportive of my older brothers’ creative efforts. I was born in 1981 and they were a decade older. As far back as I can remember, they were playing music in the house. Hair metal. They eventually moved to LA. The younger of the two left behind a Casio SK-1 and a Synsonics drum machine. I got Internet access in the mid-1990s and discovered Reed Ghazala’s writings on circuit bending the SK-1. Having listened to all of the sounds in that instrument with intense focus, circuit bending was an awesome experience to intensify those sounds in an utterly unpredictable manner. Between hearing my brother’s relentless pinch harmonic work and the deeper explorations into the SK-1, I developed some specific tastes in sound at a relatively early age that persist to this day.

PC: You are known to be one of the first manufacturers to expand the Eurorack format beyond what was being offered by Doepfer at the time. When did you start experimenting with the A-100 system? What motivated you to start building digital modules for this format particularly?

SJ: I got some cheap used A-100 modules shortly after moving to Chicago, in 2006. I was studying music technology at Northwestern, and playing a lot of improvised electronic music using circuit-bent SK-1s and pedal feedback. I had known about the A-100 system for years before that, but had never encountered one in person. I went to the NAMM show for the second time that year and fell in with a nice group of friends. I spent some time with a large Doepfer system at a dealer’s display booth. I got lost in the sonic artifacts of the prototype of the Doepfer BBD module, feeding back endlessly. I had good conversations with the principals of Plan B and Livewire about their ideas for extending the Eurorack format in exciting ways (at the time, they were two of maybe a half dozen “other” companies working in the format). After getting those used modules (an A-199 Spring Reverb, the A-112 sampler, and some assorted Analogue Systems modules), I was hooked. I preferred the act of patching to working with a keyboard or tuning in guitar pedal feedback loops. I soon felt the need for some types of modules that did not yet exist, and I got tired of waiting for other companies to make them happen. I never had any luck building working electronics projects as a kid, nor had I ever laid out a working PCB. I always liked the idea of programming in assembly, but I never knew where to start. Somehow every part of this effort worked correctly on the first try and the Malgorithm (voltage controlled bitcrusher) was born. Mike Brown/Livewire then helped me out with improving the manufacturability of my designs.

Scott's workspace

Scott's workspace

PC: To my knowledge, you have a pretty firm stance on the whole digital vs. analog thread. These days it seems as if people have become more accepting of digital modules. Did you personally notice a shift in the public’s perception and understanding of digital instruments? Can you also iterate on what attracts you to working in the digital realm?

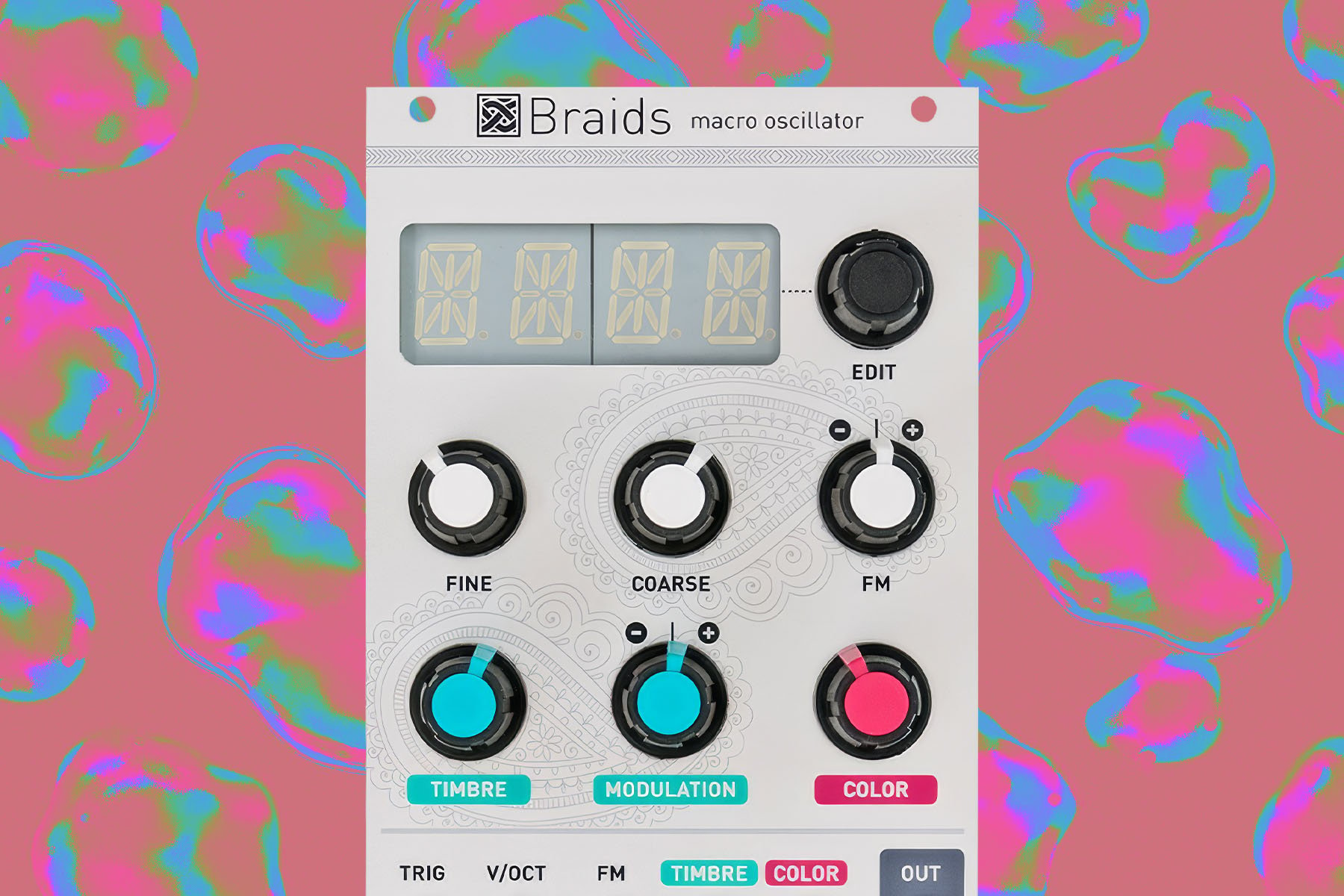

SJ: Yes, I’ve noticed. Throughout the 1990s there were some information bottlenecks preventing unrestricted online discussion or documentation of conspicuously digital synthesizers to the same degree as their discontinued analog counterparts. As the proliferation of boutique synthesizers and virtual instruments increased into the 2000s, I saw digital techniques appreciated more for their native behavior, not their imitation of basic analog synthesis. When I started designing my own equipment, I primarily focused on digital techniques because I liked the vast timbral possibilities compared to analog circuits. The character of some digital synthesizers such as the CMI, Prophet VS, and Microwave directly appealed to me and I wanted to explore further instrumentation that produced sounds in a similar space. I also started working digitally to express contempt for the analog orthodoxy of electronic instruments with realtime control. Transgression just gets easier as the years go on but it hasn’t become any less fun.

PC: Your brand has a very distinctive aesthetic both visually and sonically. Obviously even the name itself suggests a particular affiliation with harsh electronic sounds. What is the general philosophy behind Industrial Music Electronics?

SJ: Correct, the “industrial” experimental method as explored in the UK and Germany, late 70s/early 80s is the most consistent source of inspiring sounds and visuals. Most “new” music that I enjoy could be classified as dark ambient, death industrial or power electronics, natural outgrowths from that original movement with a common focus on the development of the individual will. The IME designs are certainly capable of the depths of sonic extremism you’d hear in recordings of those genres, but the devices are labeled “industrial” because they are tools designed for individuals to destroy the constraints of ideology during the pursuit of their own creative endeavors. A properly designed tool unconditionally amplifies the effort of the user, and I design such tools to help the composer oppose the increasingly stifling conditions of modern existence by successfully realizing their works. These modules do not advertise a Correct Way of Thinking, nor have they already Figured Everything Out For You.

PC: You have a history of releasing revised and updated versions of your previous designs. In some cases, like with Hertz Donut Mk2 and Mk3 or with Stillson Hammer Mk1 and Mk2, the changes between versions are so drastic, they could've easily been presented as separate modules. Is there a reason you prefer updating an established design vs introducing a completely new product?

SJ: The names are good and new ones don’t come around often. The original designs are still well loved by their users, so I consider the names as categories for specific synthesis functions even though each new iteration may significantly differ from the last. I learned a lot about design and engineering between generations of module designs.

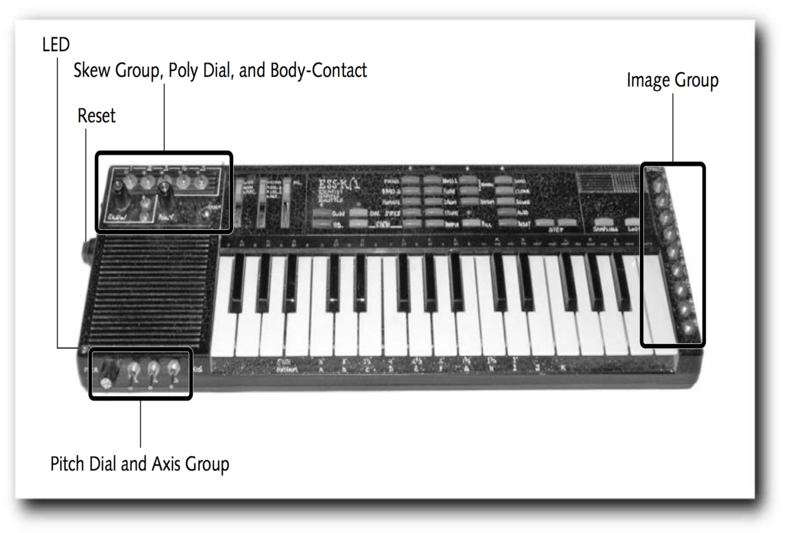

Modular Preset Manager

Buchla 200e

Buchla 200e

PC: Recently you’ve started implementing a preset system into your modules. What inspired the concept? How do you imagine people utilizing the system, and how do you use it yourself?

SJ: I had a Buchla 200e system for a few years. That had an interesting way of approaching the problem of modular patch recall, probably the first that didn’t come off as a “solution in search of a problem”. I never had the signal router module. I did have the 291e triple filter and liked it a lot. The 8-stage morphing sequencer on it was a direct inspiration for the minimal preset manager present on every IME Mark III module. I wished that the main preset manager worked more like that, where each module in the system could morph between stored states. The serial data transmission and the abundance of modal controls on the modules probably made that idea difficult, so I decided to pursue the idea with my own designs.

As I develop each module, I find that the approach to presets is different for each one. Piston Honda was the first, and I formed the most basic ideas for the new system while implementing the preset code. Hertz Donut slightly differed because there were some discrete parameters on continuous controls (the FM ratios), necessitating an option to ignore the management of certain classes of controls to achieve a smoother preset morph. Bionic Lester was designed to be almost entirely modeless, with smooth transitions between any configuration of preset in the morph mode, recalling all of the fun times I’ve had with my 291e. Kermit takes the opposite approach, with a million different modes, an ultimately tweakable swiss army chainsaw module.

PC: Currently the preset system addresses saving settings locally per module. Why did you decide to go this route over a sort of global preset management system? Do you have any plans for making a global system?

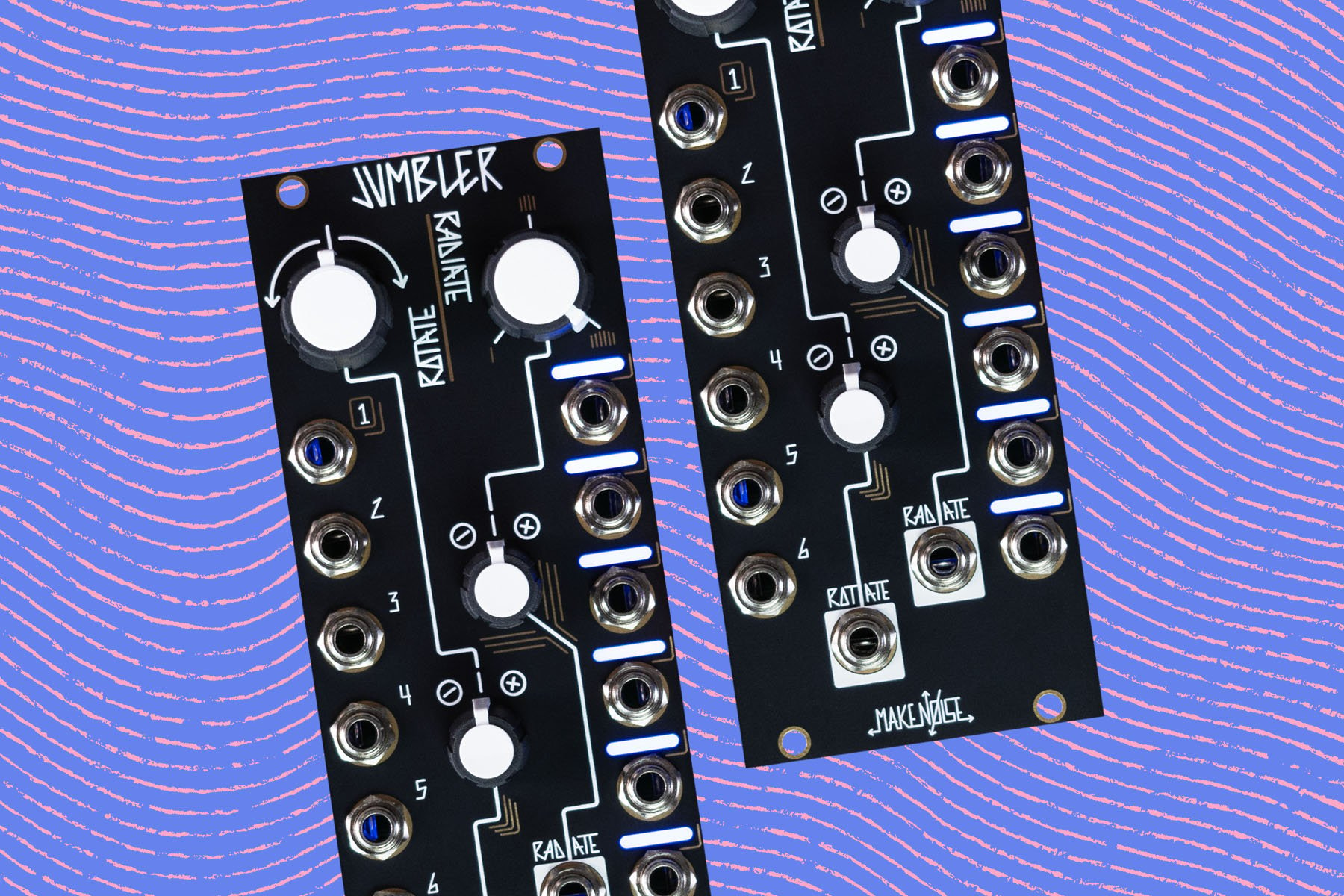

SJ: I draw the line at having anything come over the bus. Everyone has different ideas about how that works anyway, including the often-overlooked Doepfer specification. I’d call it one of those “externally enforced ideologies” that the instrument opposes in the first place, a symptom of the human drive to standardize everything. Instead, the entirety of the module’s preset memory is accessible through a single control voltage input. You don’t have to use it if you don’t want to. That preset CV input is an individual responsibility, that, if properly met, extends your realtime control of the instrument in ways that hands and patch cables never could. It’s a choice that you must make. For working with multiple mark III modules, a DC offset and CV attenuverter into a multiple is enough to do the job. A new version of Multiple Miggs is in the works with this application in mind.

PC: What about saving patch routings? Is there a way to elegantly solve this issue in modular systems, in your opinion? Or does this completely defy the original concept of preset management in the modular environment?

SJ: WMD’s [Sequential] Switch Matrix module is a great example of this. I don’t think much about storage of patch routings. My own playing style uses some simple, linear patching unless I’m in the feedback mines. I don’t want to file down the sharp corners off of everything by placing it under total control at all times. Outside of instrument design, I already deal with concepts and machinery where safety and predictability is compulsory. Extending that mindset to musical activity would defeat the original purpose and degenerate the possible results. I am mostly interested in the accidents that result in sounds that you don’t understand and will never hear again, so I’m not interested in total recall that would place much of the experimental possibility out of reach… unless it were designed from the ground up to encourage random connections instead of Documenting Everything. The limited preset system on the Mark III system exists for performance convenience. I like solutions such as the WMD module because just a small number of nodes can be switched. It has no authoritarian pretense of telling the rest of your system how to behave.

The Evolution of Bionic Lester

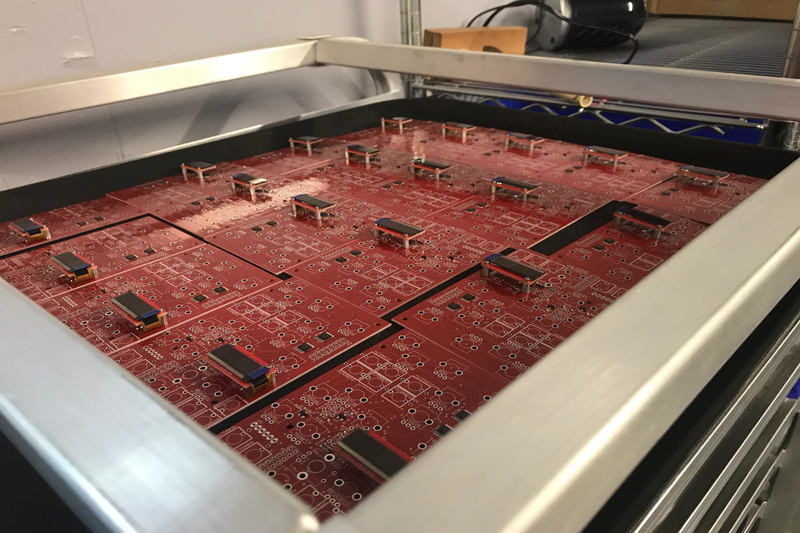

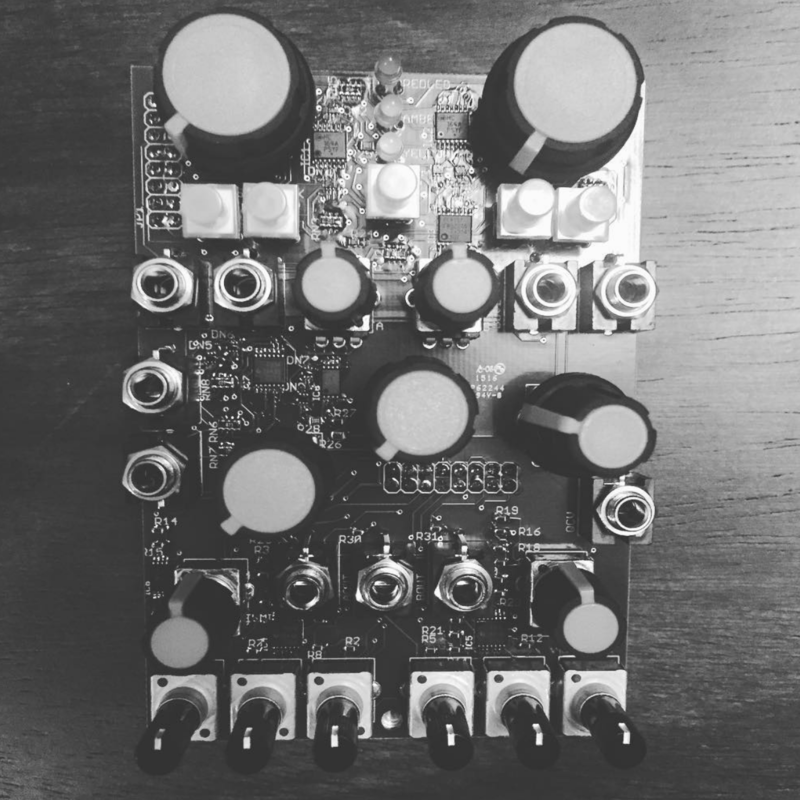

Bionic Lester Mk3 prototype

Bionic Lester Mk3 prototype

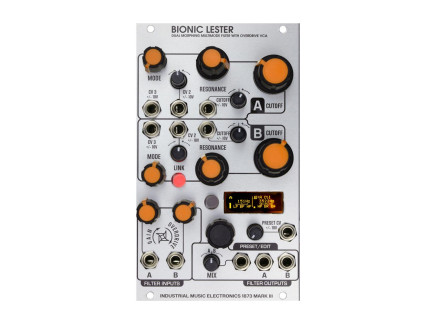

PC: We are very excited that the new Bionic Lester is coming out. Morphing filter type, stereo or dual peak operation, and the smooth introduction of soft and hard clipping sounds amazing. What are the overall differences between the Bionic Lester Mk1 and Mk3? How does this module help in shaping the complete vision of the IME Mk3 series?

SJ: Thank you for your excitement. The original Bionic Lester was released in 2011, one of the last of the original “mark I” series. It was a modularization of a switched-capacitor filter IC. Its limitations were inherent to the IC: one Q setting for both filter sections, and a cutoff frequency/clock ratio that introduced some aliasing at lower cutoff frequencies that you couldn’t disable. It had a weird allpass mode, and three significantly different flavors of distortion depending on the mode setting. The IC was in short supply and very expensive.

Still, I developed a few prototypes of the Mark II, which used the same IC with a better control layout, switchable anti-aliasing filters, and output mixers. None of the prototypes ever worked properly, and the module would have been even more expensive than the Mark III. The output mixer was more interesting in theory than in reality. The final mark II prototype included a DSP before the switched capacitor filter, intended to provide allpass diffusion and additional distortion.

The Bionic Lester fills the roles of VCF and VCA in the Mark 3 system, with full preset control. The CV inputs are assignable to any of the parameters other than the output mix. I designed it using the Piston Honda as the input oscillator for months, so the two designs can work very well together. The mark III modules have sometimes identified as a single voice when cooperation is convenient to the constituents.

Bionic Lester Mk2 Prototype

Bionic Lester Mk2 Prototype

PC: Many people think that filters are better kept in the analog domain. Where did the idea for a digital filter come from? What are the benefits and strengths of a digital filter like the Bionic Lester?

SJ: After building that final Lester Mark II prototype, I considered a digital filter design because I could keep the cost of the module down, and there was already a DSP included. I had never made one before, but I quickly discovered a character that I liked after carefully exploring nonlinearity in some uncommon places. The obvious benefit to going digital is the controllability. Bionic Lester is fully presettable and morphable in a way that would be very expensive using an analog circuit. Its character is strong enough to use as your main resonant lowpass filter in performance, but its digital nature allows for some unusual uses. It’s also very easy to change the routing between filter sections from parallel to serial (or achieve cascaded or stereo configurations) without adding any additional patchcords.

When the module was completed, it sounded good, but it seemed to be missing some of the character of my other work. First, I increased the intensity of the input overdrive. It now goes from uncolored attenuation, to soft clipping, to hard clipping over the range of the control. The intensity of the hard clipping was increased. It’s not an extreme distortion, just meant to add color to an incoming signal before filtering. If the filters are cascaded in the 4-pole mode, the distortions and resonances combine to make a sufficiently destructive effect. Next, my friend Zach suggested the addition of some comb filters. This had the benefit of replacing the formerly underwhelming allpass mode, while adding some of the bizarre digital flavor that my other designs easily reach. The resonance control now fades from allpass to heavy comb feedback (both polarities), and the cutoff control changes the length of the delay line. Finally, you can hear your musical work through the perspective of a fuel tank entry crew. Intense, evolving metallic resonances that frequently recall the freezeframe simulation of mechanical vibrations. Some friends have each ordered 2x Bionic Lesters. With two of them, one in series allpass and the other in parallel comb with some creative feedback patching and slow subtle modulation, you could easily synthesize some caveman reverb with the aid of the delay line lengths shown on the display.

I haven’t really missed having an analog filter in a small case since finishing Bionic Lester.

What's Next?

PC: You’ve mentioned that you are also working on the Andore Jr, as well as the new versions of Kermit and Malgorithm. What is the development status of these? Are there further developments planned for the Mk3 series?

SJ: Kermit is next. It’s now a 12HP 4-channel modulator with many useful modes. Two channels are fully featured. They have controls for frequency, amplitude, and waveshape. The other two channels have a selection menu, a multipurpose CV input, a combination trigger/1 volt per octave input, and two big knobs. The big channels can function as LFOs, audio oscillators, or 1-shot envelopes. The small channels commonly get used as set-and-forget LFOs, which can also operate with phase offset. There is a global tap tempo input that shows the tempo on the display, and each LFO channel can be set to oscillate at a division or multiplication of that tempo. You can write custom envelope shapes and oscillator waveforms using the WaveEdit software and load it from an SD card, just like Piston Honda. The quality of the audio oscillation is dirtier like the original Kermit, but the frequency stability is better.

The panel size is small, so there is a bigger focus on modality and multifunctional, hotkey controls. Having a preset manager makes it much easier to use. Once it’s programmed to memory, the performance utility is unparalleled.

Andore Jr. has been nearly complete for years. It hasn’t yet been released because you don’t get second chances with an analog circuit, and I’m forever making small tweaks to the layout. It is closer to a Mark II design, no preset manager. It is an analog low pass gate circuit that I used on a standalone performance instrument design years ago. This circuit has a 2-input mixer. The top half of the module has two ADSR envelopes sharing a common set of slider controls with a select button. The envelope times are optimized for note/voice/bass duty. There is a continuous control to fade the envelope curve from log to lin to expo, and the most important feature is the velocity control. You can also switch the envelopes into ADSD mode for tightly controlled sustain time regardless of input gate conditions. The idea is to provide a powerful, less expensive voice processing module ideal for small cases and live performance. An IME oscillator, Andore Jr, and a sequencer contains all the features you need for many styles of live electronic music performance. Add a Kermit or a Bionic Lester and you may convince the devices to play nice for long enough to identify as a musical instrument.

Both of these modules are nearly finished and will be the next new releases. Lately I have been working on Volkmire’s Inferno, a granular synthesizer module that I have been threatening to release since 2009 or so. The 2019 version features the Mark III morphing preset control and OLED display, stereo operation, and performs well with both live input and prerecorded files loaded from SD card.

PC: Are you still planning on expanding on the feedback console series of modules that started with the Black Locust module?

SJ: Modules are more expensive to make these days. The current state of the work is that the planned matrix mixer has been scrapped, and all focus has been to develop the feedback console itself into a single module: the Homicide Censor quad VCA/router/envelope follower, labeled “feedback console” on the faceplate. The Black Locust would attach to this module’s normal points. Of course the console would feature a Mark 3 style preset manager. Right now I plan to build a few for myself and friends, but it may find itself in regular production if user and dealer demand exists.

PC: Can you talk about your collaboration with Vladimir Kuzmin? First, what initially attracted you in the Polivoks synthesizer, and how did the collaboration happen? Second, are you working on anything new in the Iron Curtain series?

SJ: I liked the screeching, distorted character of the Polivoks filter from my earliest days of reading about inaccessible synthesizers on the mid-90s Internet, especially the weird synthesizers trapped behind the iron curtain for years. The collaboration happened shortly after I shipped my first module, the Malgorithm in 2007. One of my dealers is a friend of Kuzmin, and was interested in having a Eurorack designer adapt a few of the Polivoks modules to the format. Communication was easy and the schematics were straightforward to understand. I learned most of my practical information about analog synthesizer circuits on a backplane from studying the Polivoks. The Polivoks modules have been out of stock for a long time, but I’m preparing to bring them back in small quantities with new black aluminum knobs and slightly updated circuits.

I built a prototype of the Arton VS-34 filter, but couldn’t get the cost down enough for production. I’ve also built up a few modularizations of other USSR synthesizer circuits, but I don’t have any solid plans for those. I have a few guitar pedal designs ready to go using Kuzmin circuits.

PC: Except for the SuONOIO, most of the things that you’ve released so far were in the Eurorack format. Do you have plans for developing more stand-alone devices? And while we are on the subject, what is the status of BFF synth?

SJ: Pedals are finally happening soon. They are aware that they are to be used with guitars, and feature interfaces especially designed for that purpose.

Work on the BFF resumes soon. The Malekko people have just finished a major upgrade to Manther. My work on the BFF’s oscillator board has been finished for years, but I consider adding new features. For now I am making suggestions to the interface design.

PC: I suppose you come across music created with your devices all the time. What was the most surprising/interesting encounter in your experience?

SJ: I’ve lost count of how many of these encounters I’ve had. Most users are less overt in their use of my instruments, but many of the industrial-and-related artists I was enthusiastic about in my youth have some experience or familiarity with my work.

I also like it when power electronics agitators discover my stuff. Some US-based units have recently discovered the Hertz Donut III’s suitability for creating looping machine rhythms without external triggers, sequencer, or samples. It’s important to note that I don’t send out free gear to anyone because they’re in some band or whatever. Anyone who uses my equipment has taken a specific set of deliberate actions to pay the price of admission and learn how to use the things.

Inspirations

PC: Who and/or what currently inspires your work?

SJ: I really get into the work of people of any discipline who arrive through a self-taught path and achieve mastery while disrupting their industries. Avriel Shull, Bill Ruger, Don Buchla, there are a bunch of good examples.

Sources of inspiration: At work: The few awesome individuals I collaborate with on video, web, testing, etc, and my employees. Home life with my partner Julie. Jam Science, Thomas Garrison, JOSHUA HOLLEY, Washakie Pass, anything that Adrian Sherwood touched from 1983-87, the groundbreaking design efforts of several of my Eurorack contemporaries.

PC: Do you have any impossible project ideas—something that you would really like to create, but for one reason or another it is not feasible in this day and age?

SJ: I can realize most of my instrument design ideas now, even if they don’t make sense for commercial production. It’s fine with me if some things remain one-off concepts. As of this writing I still have all of my eyes and fingers, so there aren’t many practical restrictions on how I would design an impossible project over my remaining years. If I was able to push some knowledge of physics further into intuition, that would make things happen a lot faster.