We're always excited to get a glimpse into the minds of our favorite musicians. Often, seeing how another person approaches their craft can be incredibly illuminating and inspiring. Even if they use a similar toolset to you, it's possible that seeing someone else play and hearing them talk about their musical process can give you entirely new perspective on your own work. Or, at very least, it can inspire you to find a new way to approach the familiar.

We recently had the honor of hosting Evan Shornstein—perhaps better known as Photay—who gave us a tour of a recent setup he's been wrapping his head around. Interestingly, Shornstein's setup is intentionally designed to encourage exploration rather than to produce entirely predictable results. Check out the video above for some remarkable sounds and interesting perspectives...and read on for some thoughts about what makes Photay so interesting, and what makes this setup such a fun combination of tools.

Photay's Meticulous and Peaceful Musical Universe

I was unfamiliar with Photay until quite recently—when one of my coworkers (shoutout Wes!) let me know that he was coming in for a video shoot. With some pointers on how best to get familiar with his music, I set out on a journey of listening that, in so many words, made me regret not having found Photay any sooner.

Shornstein's bio explains quite a lot in very few words—pointing to his discovery of Aphex Twin at only nine years of age, an early embrace of drumming and turntablism, and exposure to African drumming in Guinea. As you might expect, this eclectic fusion of influences has lead to an eclectic fusion of sounds in his own work. Photay's sonic universe seamlessly evolves from one moment to a next, often with peculiar stylistic turns or fusions within individual tracks. There's a clear embrace of vintage analog synth pads, sampled percussion, field recording, warm funk production, glitchy bombastic drums, manipulated acoustic instrument sounds, and ever-present beds of noisy background texture.

Despite those all being music elements that I love on their own, there's much more to Photay's music than a grocery list of tasteful ingredients. Shornstein is clearly a tremendously gifted producer: his tracks sound deep, rich, and just plain enveloping. But more than that, they're beautifully composed and orchestrated: the sense of depth in his tracks isn't just due to savvy mixing tricks. Instead, it also owes a lot to his impeccable sense of how to layer the sounds of different instruments (electronic and/or acoustic), how instrumental forces should change from section to section, how dialogue can be created through constrasting timbres, when to remain sparse and when to get dense. Shornstein's output includes, quite frankly, some of the most tasteful dance music I've heard in ages—as well as quite possible some of the most emotionally dense, relatable, and compelling arrangements from the past several years. If you want to get lost in a blanket of meticulously-composed sound that never feels imposing, this is the thing for you. Think Aphex Twin, but chill.

Before progressing, I'd strongly recommend checking out Photay's music on Bandcamp. My personal introduction was 2014's self-titled Photay; however, 2017's Onism, 2020's Waking Hours and the ambient, hold-music-inspired On Hold would also serve as excellent entry points into Photay's diverse musical landscape. There's more than just that, though—Photay's YouTube channel is full of beautifully assembled videos that only serve to highlight his embrace of the natural world, empty spaces, and the sounds that inhabit them.

Photay's latest release is a collaboration with Carlos Niño: An Offering, out now on International Anthem. Featuring Carlos Niño on percussion, Photay on synths and sound manipulation duties, and plenty of additional sounds from other instrumentalists (harp, saxophones, and trombone abound!), An Offering is a continuously evolving soundscape of lush textures intersecting, drifting past one another, and exchanging sonic properties. Held together by the underlying sounds of wind, rivers, insects, and synthesizers, it's a continuously evolving stream of sounds that will wash over you, leaving a sense of transformative warmth. Check out the full video above, from Photay's YouTube channel, for a visually-guided path through this incredible album.

Okay, so, hopefully you now have a good sense of Shonstein's musical universe. It's deep, rich, full of environmental sound...and yet, it is meticulously detailed and very carefully constructed. But as we mentioned before, Photay came by our shop to show us his live performance setup...so you might wonder: how could all of this possibly translate into a live performance? I'm happy you asked—let's talk through his performance in our studio.

Photay's Unpredictable and Inspiring Performance Setup

In conversation with Photay, we talked a lot about reproducibility—is it important to be able to present a live performance that sounds like a record? In so many words, he told us "no...not always." In his own words, he used to be "precious" about accurately recreating the sound/vibe of his records in live performances, using Ableton and an Akai APC to present tracks in their purest form live. But lately, he's been approaching things differently.

Photay's recent work has a significant focus on collaboration (as heard in An Offering), creating contexts in which he doesn't need to occupy the entire musical space by himself. Moreover, he likes to embrace an element of surprise, discovery, and exploration in his music-making process—steering away from predictability, heading into territory where he's forced to carefully listen, react with intention, and always stay present in the moment of musical creation. An inclination toward these sorts of desires led him to acquire a new instrument in 2018...the famously peculiar, often-perplexing Buchla Electronic Musical Instruments Music Easel.

Derived from a 1970s instrument created by pioneering electronic musician and instrument designer Don Buchla, the BEMI Music Easel is a common fixture among experimental electronic musicians seeking to explore new ways of interacting with sound. Famously, Don Buchla's work evolved (mostly) outside of the growing electronic instrument industry of the 1970s and ensuing decades, continually developing on his own esoteric ideas about sound, synthesis, and interaction. And while the Eurorack world has certainly capitalized on the lineage of Buchla-inspired, so-called West Coast Synthesis, Buchla's instruments are still quite unfamiliar to the rest of the musical world. And frankly, even modular synthesists accustomed to Eurorack's embrace of "Buchla-esque" designs are often at a loss when they first encounter real Buchla instruments, which often have more quirks and character than immediately meet the eye. They might have colorful knobs, control voltages, patch cables, and LEDs, but Buchla instruments are not your average modular synthesizer, let alone your average synthesizer altogether. (A side note—if you're looking for a currently-available derivative of the Music Easel, we recommend checking out the Buchla USA Easel Command.)

Shornstein tells us that he acquired the Easel at a time when he was seeking a way to break out of his musical routine—trying to break out of his comfort zone in order to explore something new. Simultaneously, he was ready to bring practice back into his musical routine, the way that an acoustic instrumentalist practices. While modular synthesis seemed compelling, Shornstein felt that his inclinations toward relatively "conventional" songwriting made him wary of diving deeply into the world of Eurorack...but the Music Easel, on the other hand, checked all of the boxes. It was strange and new, but at the same time, it was limited: providing a user interface that you could practice and get to know over time, without the endless options that come along with a modular system.

Of course, this is much of the Easel's appeal. It's unlike most other instruments, but it's self-contained, with its own peculiar and surprisingly deep internal logic. It offers fresh perspective, but not so much fresh perspective that you feel lost—it offers a familiar, approachable interface, but it's not so familiar that you'll naturally fall back into your habits once you start to explore it.

At first, Shornstein's explorations with the Easel were just that: aimless explorations. He would often play it for hours a night, aimlessly exploring its unfamiliar workflow and alien sounds—building tracks by combining it with reverb, layering, and improvising. He discovered that the Easel really seems to be about pushing boundaries, even if they're only your own boundaries: typical 12-tone equal temperament is only one of the things it can do, and instead, much of its sound palette exists outside of our typical musical rules. Much of its tone-shaping is unlike what you'd find in the average mass-produced synthesizer. And many of its methods of interaction are unlike anything else altogether.

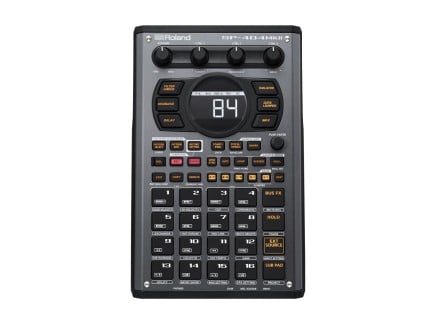

According to Shornstein, he didn't at first imagine that this way of music-making would necessarily play into his performances or record-making: it was just a way of experimenting, a way of having fun diving into the unknown. While he did start to use the Music Easel in collaborative performances, he didn't necessarily use it as the basis of many of his own solo sets—however, when he added the Roland TR-8S drum machine to the setup, it started to become clear how his experimentation could evolve into a solo performance workflow, adding more predictable, steady rhythmic bed (and providing clock information to the Easel). Similarly, the Roland SP-404 MkII sampler made an easy way to add in extra sounds—field recordings, tongue drums, strings, etc., the sorts of things we're used to hearing in Photay's music.

The sound of this setup is, no doubt, a fair bit different from many of Photay's recorded works—but all the elements are still there. While we don't hear meticulously glitched-out sample percussion, warped wind instruments, or larger-than-life, pseudo-orchestral electronic arrangements, we do hear the embrace of melody and harmony, a love of warm, enveloping textures, and the use of sound as an environment for the listener. It's enthralling to hear, and enthralling to imagine what it might become. In his own words, Shornstein didn't at first imagine that this workflow would be the sort of thing that would wind up in records...but now, he sees that boundary blurring, and sees this type of experimentation bleeding into the rest of his musical life.

When You're Left With Only Your Instincts

The Easel is no doubt an interesting instrument, but there's something more interesting to this altogether: when a musician is presented with a set of tools that more-or-less conforms to things that they're already familiar with, then it's easy to fall into habits. Of course, there's nothing wrong with that—there's plenty of good music that has been made in 12-tone equal temperament, with standard rhythms, chords, etc. There's plenty of good music that still hasn't been made that will use those techniques. But as a musician, sometimes, relying on these familiar techniques can feel limiting.

Presenting yourself with a set of tools that are unfamiliar to you can be a way of breaking past musical habits and muscle memory, and for many, that is one of the most thrilling ways to make music. What if, instead of relying on the chord shapes or fingerings or rhythms you've already internalized, you could instead be presented with something that just doesn't do those things as gracefully? What if you're presented with a tool with which the techniques you're familiar are only a tiny percentage of the possibilities?

If you're as thoughtful a musician as Photay, you'll find that this type of experience can lead you to hearing things in an entirely new way. It can cause you to listen more deeply, to relate your physical interactions to sound with greater intention, to understand timbre in a new way: and in my opinion, this type of listening is one of the best forms of practice an electronic music can engage in. When you can embrace situations in which you don't entirely know what you're doing or what to expect, you can tap into your musical instincts in a way that can be difficult with instruments, interfaces, or musical languages that are otherwise familiar to you.

And when you're left with only your instincts, you'll no doubt start to create something that no one else could make: something that is true to your own inner voice, whether you mean to or not.

Remember, Photay and Carlos Niño's new record An Offering is out now on International Anthem. Check it out, and check out the rest of his work—and be ready to be immersed.