Moog has a long history of producing synthesizers. What you might not know is that the very first prototype of the Moog Modular, built in 1964 and referred to by Bob Moog and Herb Deutsch as "The Abominatron"—was originally polyphonic. This makes sense, because other valve-based electronic synthesizers at the time were polyphonic; the RCA Mark II installed at Columbia University in 1957 could play several notes at a time, for instance. Going back further, we have the Hammond Novachord, which was fully polyphonic using a divide-down oscillator architecture.

There are many other examples of early polyphonic electronic instruments. However, the Moog Modular, a distinct turning point in the devleopment of electronic musical instruments, was nonetheless monophonic.

Polyphony

When we talk about polyphony, we often find ourselves wandering into disputed territory. It would be good to define it otherwise, we might find ourselves discounting a Moog synth because of a lack of clarity. Is it simply down to the number of individual notes that are being sounded, or is the articulation of the voice architecture also a factor? We have other terms, such as monophonic, duophonic and paraphonic that appear to pull at polyphony in different ways.

So, for this article (and I am deferring to synthesizer historian Marc Doty in this), I will define synthesizer polyphony as being when a synthesizer can play more than two notes or voices at a time. A "note" is simply a single frequency, whereas a "voice" is a structure that is articulated through timbre and amplitude modulation, like a filter and VCA. Polyphony doesn't care whether the note is articulated or not. Many people believe that to be polyphonic each note must have its own filter and VCA and be fully articulated as a voice , but this is not true. The term "paraphonic" has arisen to describe multiple notes that share a single filter and VCA articulation. However, that has no impact on its polyphony or how many notes it can play simultaneously.

Sonic Six

At the start of the 1970s, Moog had moved on from the modular approach to craft the extraordinary Minimoog Model D—a resolutely monophonic, three-oscillator subtractive synthesizer that was foundational in making the synthesizer musically accessible to everyone. However, the existence of a keyboard brought the expectation that you could play it like a piano and, for instance, play chords—and to some, it was a source of disappointment when you couldn’t. Polyphony was important to many keyboard players (which makes sense), and this need would shape the development of synthesizers over the following ten years.

Despite the success of the Minimoog, Bob's company, R. A. Moog needed investment and so merged with Bill Waytena's synthesizer company muSonics, to become Moog Music. Bill intended to market synthesizers to home and educational users, but felt he needed a known brand name to get that going. Before the merger, muSonics had a synth designed by Gene Zumchak, an ex-Moog employee, called the Sonic V. Bob took the design, made a few tweaks, fitted it into a flight case and renamed it the Sonic Six. It had two oscillators, was duophonic (2 notes at a time), and so is arguably Moog's first polyphonic synthesizer.

Bob had patented the Moog ladder filter, so when muSonics built the Sonic V they had to use a different filter design. As such, initially, the Sonic Six had a very different tone to the Minimoog—but in later production runs, they replaced it with the Moog transistor ladder design. Oddly enough, later runs of the Minimoog used the Sonic Six VCO design, which was more stable than the original.

Apollo

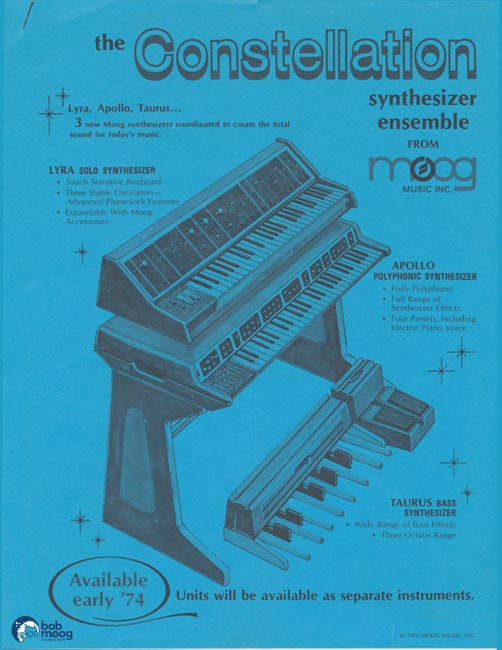

The ability to play chords was still elusive in synthesizer terms. Between 1972 and 1974, Moog engineer Dr. David Luce worked on a concept synthesizer system called Constellation. It was an ensemble in three parts: the Lyra monophonic synth, successor to the Minimoog; the Taurus bass synth built into an organ-style pedal board; and the Apollo polyphonic synthesizer.

Moog Constellation ad; image via the Bob Moog Foundation

Moog Constellation ad; image via the Bob Moog Foundation

The Apollo was designed around the divide-down principle of using 12 fixed-frequency oscillators to cover the top octave and then using time division to clock the oscillator waveforms down to lower octaves. This enabled it to play every single note on its keyboard simultaneously. However, the technology didn't exist to provide each note with individual signal routing and articulation, so it had a single Moog filter, VCA, and envelope. Consequently, it had massive polyphony…but only paraphonic articulation.

The Constellation prototype was loaned to Keith Emerson, who used it on the Emerson, Lake and Palmer album Brain Salad Surgery. The thing about paraphonic articulation is that if you are playing chords, then it sounds just like a synthesizer should; you have that filter shape over all the notes, and it's great. However, if you play it like a piano, with a complex interplay of notes, then each time a new note is struck, the single filter is retriggered over all the notes, and that's just plain weird. For Emerson, who was a keyboard wizard, the lack of articulation for each note was a real problem.

The Apollo never made it into production—and the surprise star to emerge from this endeavor was the Taurus bass synth. Apparently, a couple of Lyras were sold, and the Lyra concept eventually led to the Multimoog.

Polymoog

Luce took Emerson's criticism of the Apollo on the chin and returned to the drawing board. Around this time, Yamaha released the behemoth GX-1, which was part theatre organ, part synthesizer, and part drum machine and weighed over 650 lbs. The top keyboard was a monophonic synthesizer, but the other two were 8-voice polyphonic synths with two oscillators per voice. The GX-1 showed that generating polyphony by creating a voice card, which was essentially a complete monophonic synth on a card, was technologically possible, if largely impractical.

Other innovations came from Emu, such as their 5-octave digital scanning polyphonic keyboard, which was built for the E-mu Modular system. It unlocked the puzzle of how to assign a limited amount of voices to the notes that were played. This technology would make it into the hands of both Oberheim and Sequential over the next couple of years for their polyphonic synthesizers.

Back in the Moog workshop, Luce persisted with the octave divide-down technology from the Apollo. Solving the articulation problem would require building individual synthesizer voices, like the GX-1, but for every note, and with current technology, this would be practically impossible. He solved the problem by designing a new "Polycom" chip that included a discrete filter, amplifier and two envelope generators for each of an instrument's keys. So, combining the divide-down oscillators with the Polycom chip meant that every note had its own articulation. He quite rightly named the resulting instrument Polymoog.

It was an immediate success despite its $5,000 price tag, and, along with being fully polyphonic, it had some other unique innovations. It was velocity-sensitive, bi-timbral, had a 3-band EQ—and even with 71 keys, it was somewhat portable. In 1975, the Polymoog was regarded as an absolute dream machine of a synth and endorsed by such luminaries as Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, and Michael Boddicker (check out the amazing promotional video). But not everything was quite as it seemed.

The Polymoog leaned into its organ/string machine heritage by having eight presets or “modes.” These were String, Piano, Organ, Harpsi, Funk, Clav, Vibes and Brass. The sounds were defined using the 71 filters and amplifiers, along with velocity and timbre articulations to be fully polyphonic. However, you had no real control over the filters—so trying to use the presets as a basis of exploring the synthesis was limited to oscillator detuning and level contouring. There was a ninth mode called "VAR", which was designed to be the programmable user mode. Unfortunately, this did not include access to the preset defining voices. Instead, you had two programmable filters for the whole mode; a fixed filter bank called a Resonator and a Moog VCF. So, outside the presets, it felt very much like the Apollo with its unsatisfactory paraphonic filtering and envelope retriggering.

Bob Moog endorsed the Polymoog in its marketing, but wasn't involved in the design. He left in 1977 to set up a new electronic music company called Big Briar, and resumed using the "Moog" name in 2002.

In 1978, Moog released a stripped-down version called the Polymoog Keyboard 280a. It had more presets, less control over the sounds, but you could split the keyboard to produce a separate bass tone and was much less expensive. Gary Numan famously used the Vox Humana preset on his track Cars. It was considered to be a pretty desirable synth for live performance, and it had a useful ribbon controller and lots of connectivity.

[Above: Alex Ball's fantastic video on "That Gary Numan Synth."]

However, by this time, the GX-1 had morphed into the phenomenal Yamaha CS-80, and Sequential had released the Prophet-5, which was the first commercially-available polyphonic synthesizer to have a fully programmable memory. Despite their limited polyphony, they were hugely successful and offered lush-sounding waveforms. By comparison, the Polymoog was limited in tone, frustrating to use as a synthesizer, and was plagued with reliability issues. The divide-down method was great at producing polyphony but sounded a bit weak compared to the warm tones Moog pioneered in their monophonic synthesizers. Both Polymoog models went out of production in 1980.

Opus 3

Moog would finally get their act together with the Memorymoog in 1982, but before then, they dallied with the divide-down structure in two and a half more polyphonic synthesizers.

In 1980, Moog released the Opus 3, which was essentially an ensemble instrument with three sound engines. The available sections were the ever-popular Strings, Organ, and Brass. The straightforwardness, controllability, and full range of polyphony made it very popular with gigging musicians who would be using those sounds all the time.

The Strings section has a familiar sawtooth synth sound, an octave range switch and a remarkably Moogy multimode filter. Unfortunately, it doesn't have any articulation, so you either set it to what you like the sound of or manipulate it by hand. For the Organ section, you have five sliders that bring in different octaves of square waves, emulating the idea of tonewheels. It has a tone control that removes harmonics from the square waves until you have sine waves. Finally, the Brass section is routed directly to a Moog ladder filter to give you that classic synth-brass sound.

There's an LFO for modulation, a Chorus effect, and you can play all three sections at once, ending up in a three-channel stereo mixer. While the synthesis is relatively simple, the Opus 3 can generate a range of very usable synth sounds that were perfect for the music of the time.

Liberation

In the same year Moog released the Liberation "keytar." It was a remarkably elegant synthesizer baked into a guitar-style form that you would hang around your neck. Where the fretboard would be, you would have a long ribbon controller and spring-loaded wheels for filter cutoff, modulation, and volume. It looked fantastic on stage and had a 40-foot cable that connected it to a power supply and a bunch of CV/Gate output sockets.

The primary synthesizer consisted of a two-oscillator monosynth. You had different wave shapes, a mixer, modulation and the Moog filter. However, it also had a single polyphonic divide-down oscillator section that appeared as "Poly" in the mixer, which runs paraphonically through the single filter. The ability to mix the poly section in with the other oscillators gave the Liberation a big, 3-oscillator feel.

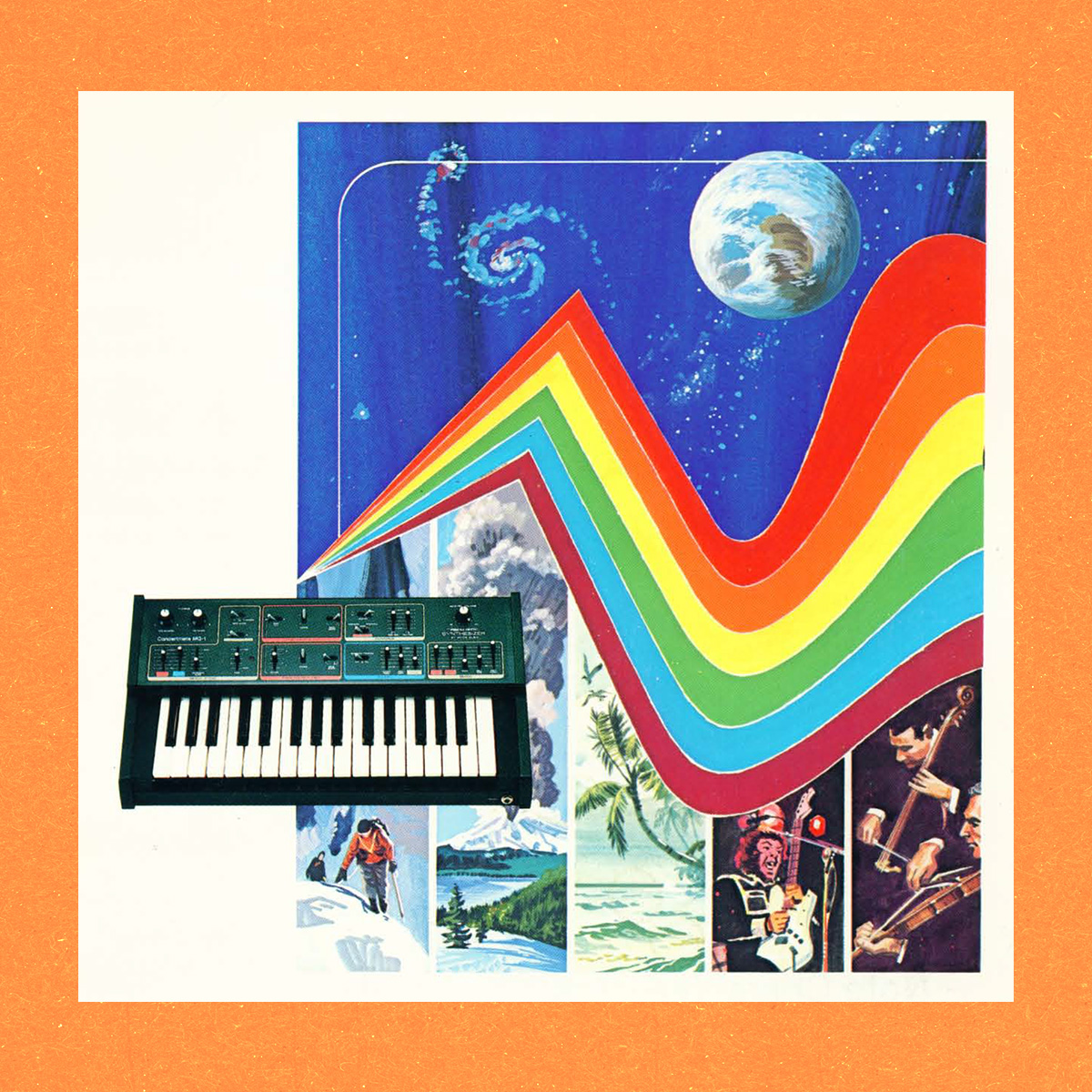

Realistic Concertmate MG-1

The Realistic-branded Concertmate MG-1 came about through a misadventure with the Radio Shack network of electronics stores.

The idea was pitched to Tandy/Radio Shack by Luce in 1981 at one of their infamous annual 90-second pitch days. With just a breadboard prototype and one and a half minutes of fast-talking, he spiked the interest of Radio Shack's Bernie S. Appel, which was just enough to get it green-lit. Moog was used to spending months developing a product, but when the schematics were sent to Tandy's product engineer Paul Schreiber (of eventual Synthesis Technology fame), he was given four weeks to prepare it for a Radio Shack price of $499.95. The only guidance he got from the head office was that all the notes had to play (polyphonic), and the connections needed to be RCA so they would plug into other equipment they sold.

So, in conversation with Moog, Paul sourced the parts, simplified the synthesis, made the labelling more user-friendly and added some color. It had two oscillators, a voltage-controlled filter with keyboard tracking, Contour envelope controls, modulation and a mixer that added noise, a bell tone ring modulator (taken from Tandy's work on telephones), and a similar polyphonic organ section that we found in the Liberation.

There's some disagreement on the internet over whether the MG-1 was based on the Moog Rogue, which arrived around the same time, or the other way around. They did, after all, share the same shell. According to the Radio Shack archives, the MG-1 first appeared in the 1982 catalogue, printed in the summer of 1981 and posted out that September. The actual product would have to be in the warehouse ready for distribution by June of that year to reach the stores in time for the catalogue release. The Rogue's first appearance was in The Moog Newsletter in June 1981 and was first seen at the Chicago NAMM show later that month. So, it's most likely that they were developed at the same time and were simply different versions of the same design. The monophonic Rogue lost the polyphonic organ and ring modulation, gained pitch and modulation wheels and was sold in music stores for around the same price.

The MG-1 did not do well. It wasn't a terrible idea, but Moog lacked the understanding that it needed to sell into the home market. Radio Shack stores had no appreciation of its analog sound or synthesizer heritage and didn't really know what to do with it. A product is given a two-year cycle in which to perform at Radio Shack, or it's dropped and sure enough, it had vanished by the time the 1984 catalogue came along. By the end of the cycle, they were blowing them out for $99. In the 1983 catalogue, Radio Shack had already added a $70 rebranded Casiotone keyboard that had preset sounds and rhythms, a built-in speaker, and even an 8-digit calculator. The MG-1 didn't stand a chance.

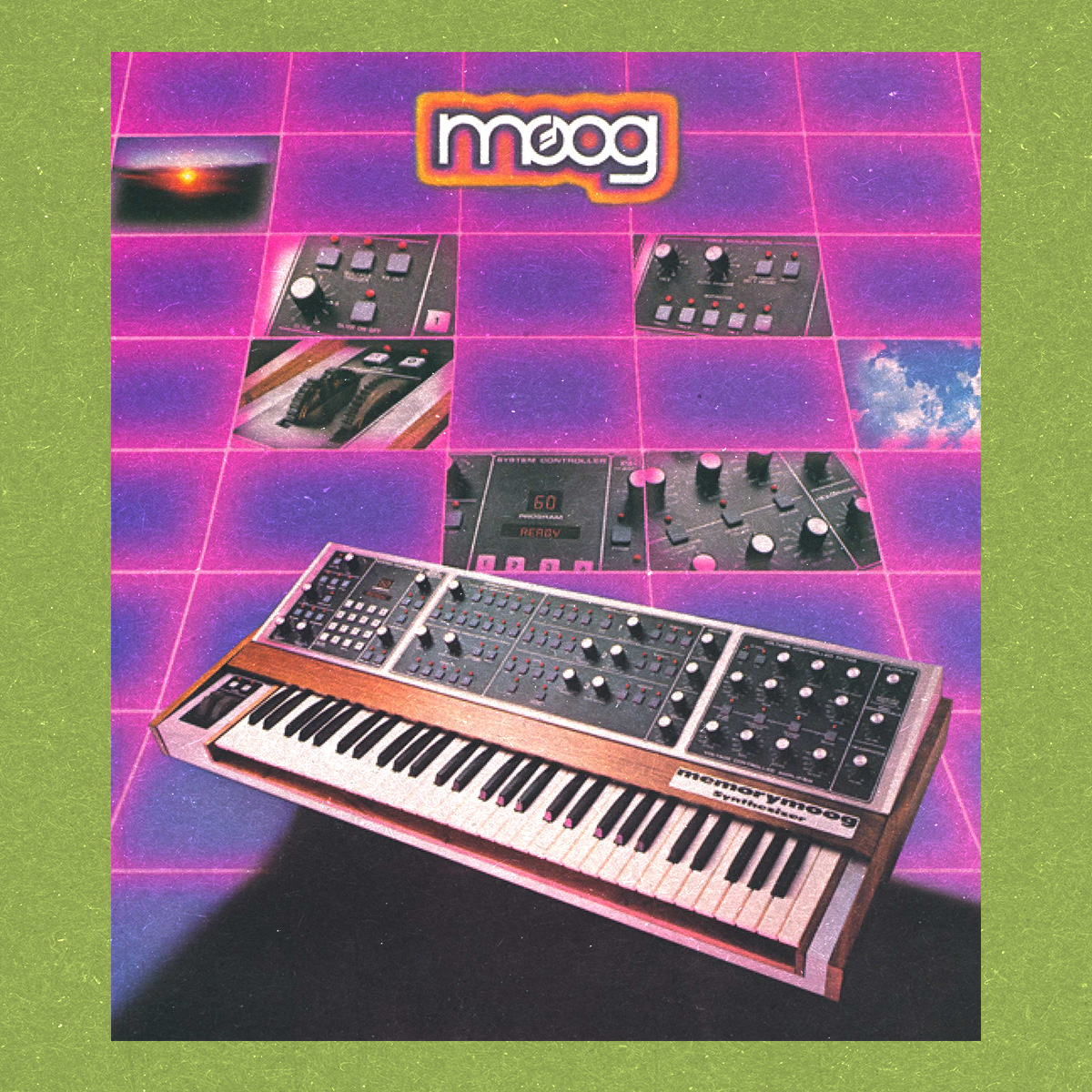

Memorymoog

At last, it's 1982, and we come to the quintessential Moog polysynth: the Memorymoog. Moog had finally shed its fascination with divide-down polyphony and embraced the concept of individual voice cards that contained oscillators, filters, VCAs, and envelopes for each voice. The Sequential Circuits Prophet-5 and Oberheim OB-Xa had already been hugely popular and led the way in demonstrating how useful limited polyphony could be across a whole keyboard. Roland also released the extraordinary Jupiter-8, which brought a futuristic aesthetic to analog synthesis. Meanwhile, emerging around the edges we had the digital revolution of the Fairlight, Synclavier, and PPG Wave starting to have an impact, and we're only a year away from the arrival of the infamous Yamaha DX7.

So, very late into this wild mix of heritage, futurism, analog and digital polyphonic profusions of musical technology, the Memorymoog arrives.

The Memorymoog was essentially six Minimoogs in a single case, albeit with updated Curtis CEM 3340 oscillator chips. A Minimoog had three oscillators, so the Memorymoog became the first polyphonic synthesizer to have three oscillators per voice. On top of that, each oscillator could have a different waveform. In total, it had 18 VCOs, 6 VCFs, 6 LFOs, and 12 envelopes, and was able to generate six fully articulated voices. It was uncompromisingly analog, with classic looks and the warm Moog sound that everyone had been waiting for.

At the time, the modulation options were huge. Each voice had an LFO, but VCO3 could also be used as a modulator, giving it a very rich and movable sound. The envelopes could be routed to pitch and pulse width, inverted, and used to contour the depth of VCO3, contributing to some great FM action. The filters were fat and fruity, full of overflowing resonance, and you could overdrive the signal path. With the pulse width modulation, sync options and noise generator, it was one truly powerful-sounding synthesizer.

The "memory" aspect of the Memorymoog was the 100-slot, Zilog Z80-based System Controller for storing patches, auto-tuning, and managing voices. It was the first synth that could display both the current parameter value and the original for comparing sounds. You could even passcode the keypad so that no one could mess with your patches.

However, for all its gorgeous polyphonic sound, interesting modulation, and powerful oscillators, it was all a bit too late. It lacked split or layering, there was no CV input for sequencing, and it arrived just as MIDI was about to revolutionize the synthesizer world. The Memorymoog+ was released quite quickly, adding rudimentary MIDI control and a sequencer but it wasn’t quite solid enough. They had some success marketing it into the Christian worship market by rebranding it as the Sanctuary. However, in the face of the more convenient, cheaper, and future-facing digital synthesizers, they couldn't hold people's attention—and they were discontinued in 1985.

SL-8

Moog Music attempted to pull in some digital expertise and get a foothold in the new revolution. As early as the summer of 1983, they had a prototype of the SL-8 available to view at the summer NAMM. It was an 8-voice polyphonic synthesizer with digitally controlled oscillators that could be split and layered. Purportedly, the voice cards were in a cardboard box under the table and connected via ribbons to the prototype front panel.

The SL-8 never made the light of day; by 1987, Moog Music was out of business. It wasn’t until 2002 that Bob Moog got the name back and resurrected the brand. Buoyed by a rising interest in analog hardware, Moog Music found itself at the forefront of a new analog revolution. While most of the new products were monophonic, it was only a matter of time before the desire for a big, analog polysynth would once again be on the agenda.

Moog One

In 2018, over 30 years since the demise of the Memorymoog, Moog Music introduced the Moog One. Parallels with the previous polysynth in style and intention are obvious, but there's a lot going on in this reimaging of the analog polysynth.

There are three VCOs per voice, newly designed with ring modulation, waveshaping, and FM, but this time, you have two independent filters, a multimode variable state filter, and a classic Moog ladder filter per voice. It has three envelope generators, four assignable LFOs, two noise generators, and an overdriveable analog sound source mixer. The signal path is fully analog until you reach the digital effects section, which is bypassable if you don't want bits and sample rates messing with your audio. It has a 20-slot modulation matrix, a chord memory, arpeggiator and polyphonic sequencer.

The Moog One is actually three polyphonic synthesizers that can be stacked, layered or split to share the standard 8 voices (or 16 voices if you opt for the expanded model). They can be completely independent with their own effects, modulation, arpeggiators and sequencer.

This is an epic synthesizer with a huge sound and massive range of sonic capabilities at a breathtaking price point. It's deep and potentially overwhelming, but it has a very open and intuitive front panel. There's a lot of digital wizardry under the hood and a central panel with which to control it all. There's no doubt that the Moog One has fulfilled the 30-year dream of a new Moog polysynth. However, it's not been a perfectly smooth journey. There have been issues with cooling and the fans' noise; various firmware updates have attempted to handle “quirks” and missteps in the original release while adding further complexity and capability.

Regrettably, the Moog One has been discontinued in favor of the new, much more affordable, and streamlined Muse—more on that later. I think it's unlikely we'll see another synthesizer from Moog on the scale of the One…at least, any time in the near future.

Matriarch

Meanwhile, back in a more affordable realm, Moog has been doing interesting things in the semi-modular marketplace. Following on from the well-received Grandmother monosynth comes the Matriarch semi-modular analog synthesizer. Its four oscillators can be played independently, giving it four notes of polyphony which are articulated paraphonically through dual analog ladder filters and VCAs. It has two LFOs, two envelopes, a stereo delay and a polyphonic sequencer/arpeggiator. The 49-note keyboard has velocity and aftertouch, along with pitch and mod wheels.

Perhaps more interesting is that it has 90 patch points for modular rewiring and modulation. It works as a little modular playground to enable you to explore signal routing, feedback loops and advanced modulation. It's beautiful to look at, available in both snazzy colours reminiscent of those early polysynths, and in a very serious black. It's expensive compared to synthesizers from other companies, but something about the Matriarch seems to capture the essence of that unmistakably special Moog vibe.

Muse + the Future of Moog

Editor's note: The rollout of new products from Moog has been slowed since their acquisition by InMusic in 2023; however, we've now seen the release of Spectravox, Labyrinth, and most recently, Muse—the latest chapter in the history of Moog's polyphonic synthesizers. Muse was announced after Robin Vincent prepared this article, so from here, I'll speak from my own perspective.

Muse borrows many concepts from One, with a streamlined user interface and internal logic. It's an eight-voice polyphonic synthesizer with two oscillators per voice (or three, including the per-voice analog modulation oscillator), two filters (with series, parallel, and stereo routing options), and a unique diffusion delay, allowing everything from chorus-like effects to dense multi-tap repeats.

Muse is bi-timbral, allowing for splits, layers, and interesting adaptive voice allocation tricks; it has an arpeggiator and a complex sequencer with probability and more. Add to that complex LFO shapes, looping envelopes, a 16-slot modulation matrix with voltage processing "transforms", and a 61-key, velocity-sensitive, aftertouch-capable keyboard, and you have an instrument with a tremendous amount of promise.

The Muse is still young, but we have no doubt that it will take Moog's polysynth story into a new era.

Robin Vincent would like to thank Paul Schreiber for a very enlightening phone call and Marc Doty for his historical knowledge.