There’s a saying that in order to start something you need to have motivation, but to finish it, you need determination. Corry Banks has both. A pioneering figure of the Modbap community, Banks draws from myriad experiences, well-honed skill sets, and a keen vision to bridge the gap between modular and hip-hop. From running BboyTechReport, a website for beatmakers; to BeatPPL, his brand for music, sound design, and sample packs, as well as the name of his record label; to founding Modbap Modular, the first Black-owned and designed Eurorack company, Banks is not only part of a movement, he is movement.

With a crew of like-minded artists and creators such as Ali the Architect, Ken Flux Pierce, and Voltage CTRLR, Banks recently released the compilation, Diggin’ In The Wires, on his BeatPPL label. The double-LP featuring members of the Modbap community pushes the boundaries of modular synthesis out of its drone/noise/looping arpeggiated comfort zone and into new musical territory.

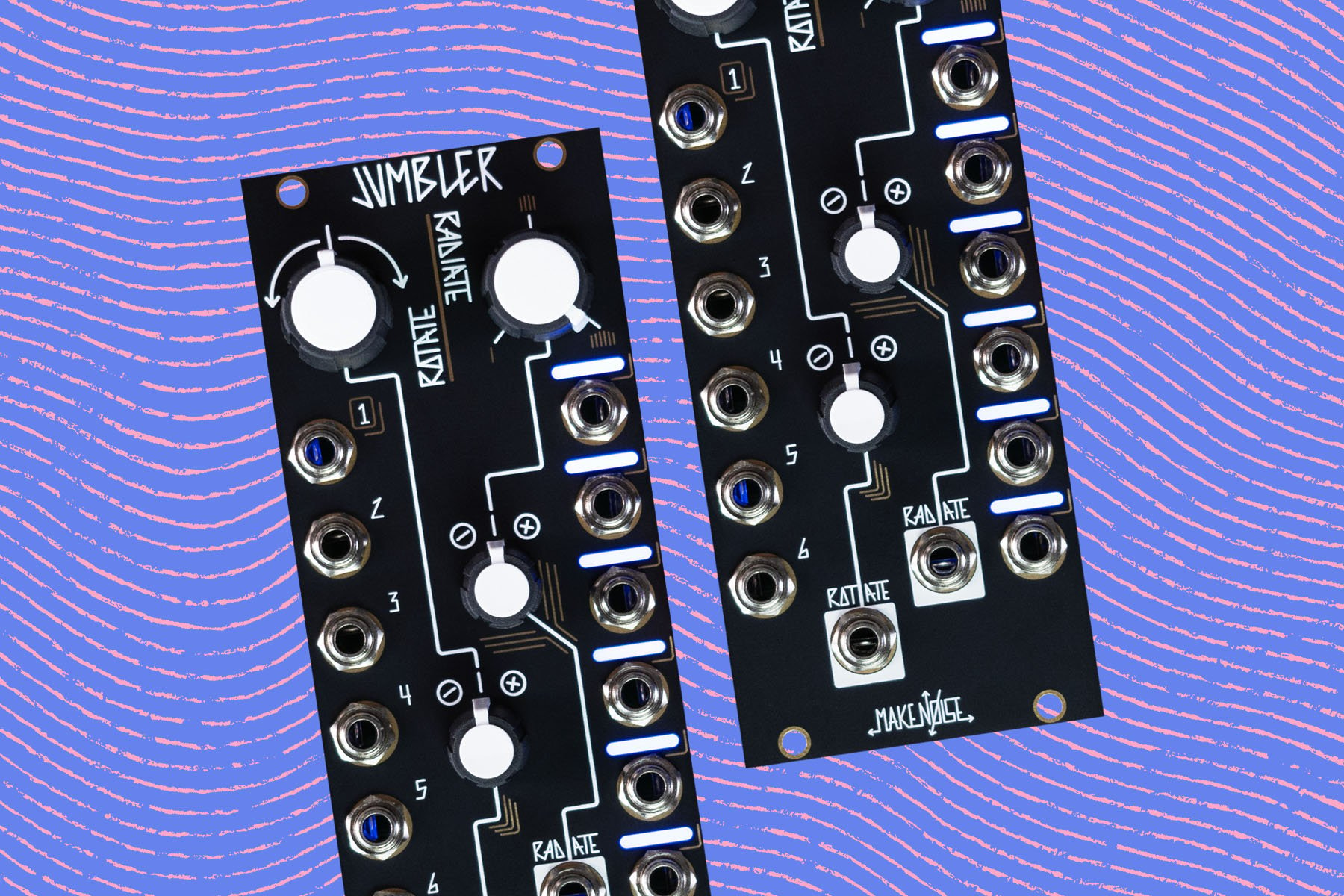

In 2020, to help facilitate his sound, his Modbap performances, and to get his live setup just right, Corry designed and released his first Eurorack module, Per4mer, a quad performance effects tool complete with four large vintage video game buttons. A new wavetable module, Osiris, has recently been released and finds Modbap Modular expanding its line, and bringing him one step closer to his perfect performance rig.

Corry was gracious enough to talk to us about his world, and shed some light on how he balances everything, and to tell us if he’s finally achieved perfection in his live setup.

An Interview with Corry Banks

Corry Banks, founder of BBoyTechReport, BeatPPL, and Modbap Modular

Corry Banks, founder of BBoyTechReport, BeatPPL, and Modbap Modular

Ellison Wolf: So you live just outside of LA. Are you from California originally?

Corry Banks: I was about 30 when I moved to California, I'm originally from the west side of Chicago—I was born and raised there. I went to school on the north side—Lakeview High School—in the same area with Cubs stadium, Wrigley Field. So yeah, Chicago boy.

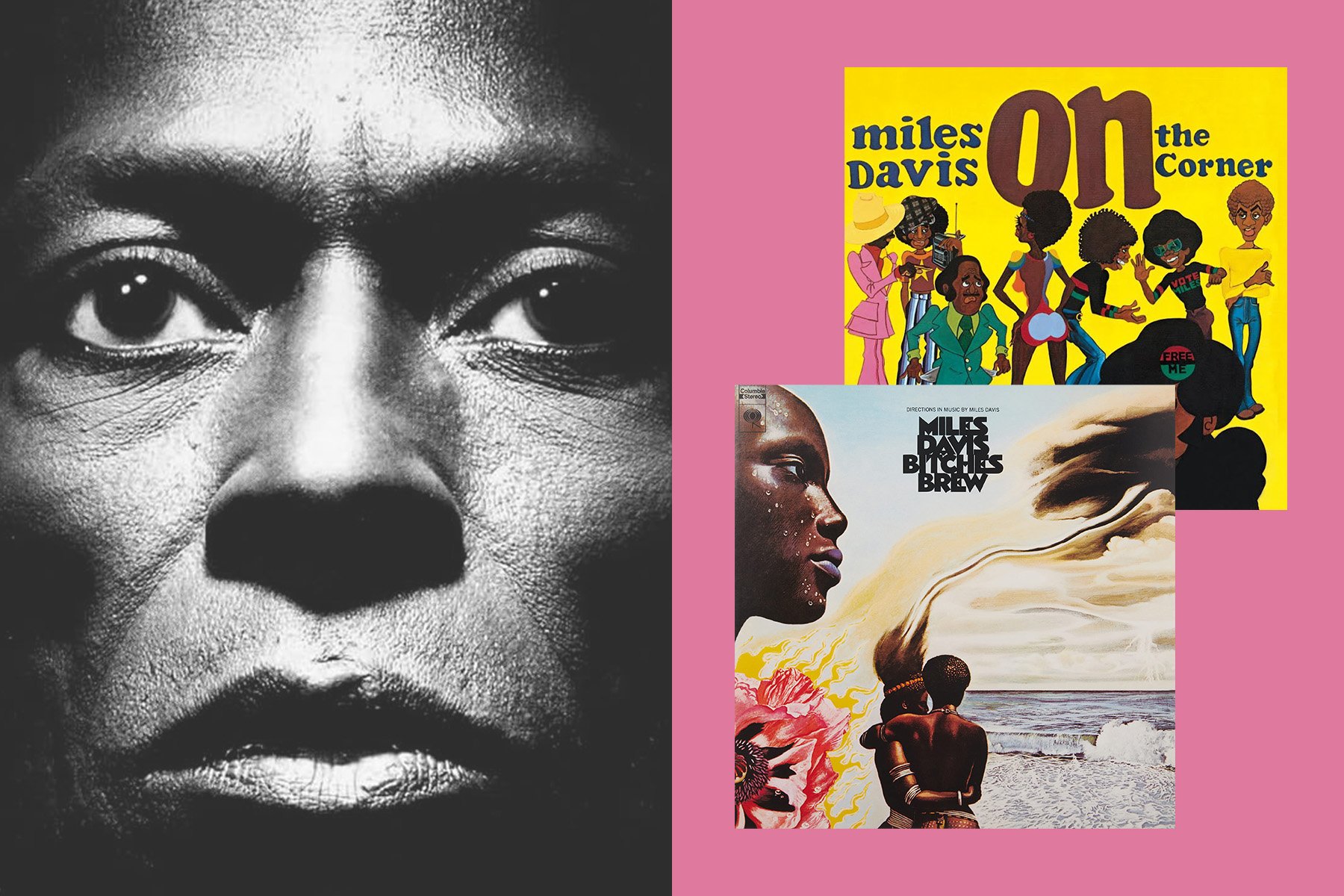

EW: Were you big into the music coming out of Chicago as a kid?

CB: I came up in 90s Chicago hip hop, and was in a couple rap groups. The group I was in for the longest signed a production deal. We basically lived in a studio, did a lot of shows, everything from NAACP [shows] to opening up for the who's who of hip hop in the 90s. We were nominated for Best New Rap for the Chicago Hip Hop Awards. Good times.

EW: How did you go from being on stage and performing into the production side?

CB: When 2000 came around, the group I was with at the time were just on different pages, so we started going our separate ways. I realized that I was bouncing around Chicago too much trying to find chemistry with a producer, so around 2002 or so I bought my own MPC; I had a homeboy, my best friend, that was a DJ and beatmaker for the group who taught me how to use it, and that’s how I started just making my own music. Before I left Chicago, I had a band, kind of like The Roots, with me as the lead vocalist / emcee. I would make beats and create songs and the guys who had a band would learn those songs and backed me up when I performed. So we started rehearsing a lot, pooled our resources, and so from that kind of experience we became a band performing all around the city.

EW: How did you like being a band leader in that sense?

CB: I really didn't even think of it like that, but in retrospect, I was the band leader. I was fortunate enough to have musicians that—since I wasn't trained—could help me to embellish and arrange my songs. I’d then arrange the sets and we’d collaborate on how things would go from one thing to another when we were transitioning from song [to song], so that was really fun. Being able to say, “Right there, at the third verse, let's not do the regular song thing, [let’s] cut into this well known groove of this popular song.” I loved that and it gave me confidence as a producer and performer because these were trained musicians and I was able to put together things to work out and arrange live shows for our band.

EW: Why did you leave Chicago to come to California?

CB: It was just one of those things. After the first time I came to California for a visit in 1998, I just couldn't get it off my mind. I knew I had to live here. I started getting into technology as a career in the 90s, but I'd never stopped doing music and performing and emceeing and making music, and these worlds kind of collided. Ultimately, once I started my IT career, I happened to work for a law firm that had a office in LA and so anytime somebody said, “Hey, we're going out there to do a project and need some help,” I volunteered to go, and they got to know that if there's going to be work done in California, Corry is going to be on the list to go. So, I was on a project in LA in 2005 and had a few conversations—one thing led to another and three months later, I moved to LA with a job, put together a hip hop band and kept doing what I was doing. It just worked out really well.

EW: So when you moved to LA you formed another band?

CB: Pretty much almost immediately, because I was here for three months by myself before my wife and daughter moved out, and I found myself in LA with no family and friends, so I came out to put my flag in the sand and stake my claim. You can only volunteer for so much OT [over-time]. So I put together a band [through] Craigslist, just put ads out and a DJ came to my crib. I found a bass player, a drummer, a keyboardist, and this incredible vocalist, and so we became a band, and we rocked pretty hard. It was good.

EW: When I lived in LA I put a band together with the Craigslist thing too. And I'm still friends with some of those people. In LA, people kind of have this similar focus to pursue their dreams and it connects you.

CB: It definitely does. I was the front man, and it was my music that we were basing everything on, but it really felt like they were teaching me a lot. We were rehearsing all over the place, so I got to learn the city by constantly driving to all these places, or going to their places to hang out. It was a great time and I learned a lot about LA.

EW: Were you into programming back then?

CB: Yeah, really heavy. At that time it was an MPC 2000 XL that I’d initially sold to move to LA. I ended up getting another one because your first piece of gear you always kind of have a soft spot for. I also had an E-mu PK-6 and a MicroKorg. It was just a little setup with a computer and so I was programming all the beats and stuff, and I would email it to the band. They’d get familiar with it, and we’d practice it on the weekend.

[Above: Corry's first hardware setup.]

EW: Were you incorporating the stuff you wrote on the MPC and on your synth setup into the music or was it mostly like a writing tool?

CB: We would perform it live with their interpretation of what I had created, and that was a struggle. My wife and I talked about it around that time. She'd say, “I like your music, and I like what you perform, but I think I like your recordings better.”

EW: Yeah, that happens. In the studio you’re free to do anything, to make it yours.

CB: That was always a struggle, and I knew that the next next hurdle was going to be recording with the band. I felt like that was gonna be the biggest headache, and we never got there. After a couple years of performing with the band, it became such a hassle. Anybody who's ever led a band or been in a band knows the kind of hassles and I started really liking performing with only me and my DJ because I could perform the tracks that I created, just as they were created.

EW: Do you still perform?

CB: I do Modbap and live electronic beat sets. Everything I do has got hip hop at the core of it, but I don't MC over the top of things.

Sam Chittenden: You make beat samples that you sell online. How long have you been doing that?

CB: Since sometime between 2012 and 2014. I started BboyTechReport.com, an online magazine and blog, and that progressed into me making sample packs, because I would do a “Top 10 Sample Packs” [article], or review sample packs. The whole BboyTechReport thing was/is a milestone for me because I just didn't see that voice out there represented much. There weren't many, if any, Black guys—let alone hip hop [people]—represented in any kind of way. To expand on that idea, Beatppl.com was built to allow me a space to do e-commerce aside form BboyTechReport, which is all about news, reviews, and interviews. I just started making sample packs and putting those things out there and that kind of birthed BeatPPL, which is the site that I sell all my sample packs and stuff on.

EW: I feel like we're missing a bit of a piece there because how do you come from the band and your sort of small setup with the MPC and MicroKorg to BeatPPL and making sample packs? Where does that whole rabbit hole of discovering synths and gear and then deciding that you want to review gear, as you do on BboyTechReport, come from?

CB: I was always a gearhead, and that gave me the confidence to start BboyTechReport.com. I want to be that voice on a wide scale, even if it's a niche market. I created BboyTechReport.com for a class—IT project management type stuff—but I knew that I wanted to be a real thing as well. Reviewing equipment started with apps and equipment that I already had, or stuff that I could go to Guitar Center and play around with and come back and write an article about my opinion. Companies started reaching out to me, and within the first year of me having a blog—2012—I started to go to NAMM, and at that point the floodgates opened.

[Above: Corry's current setup.]

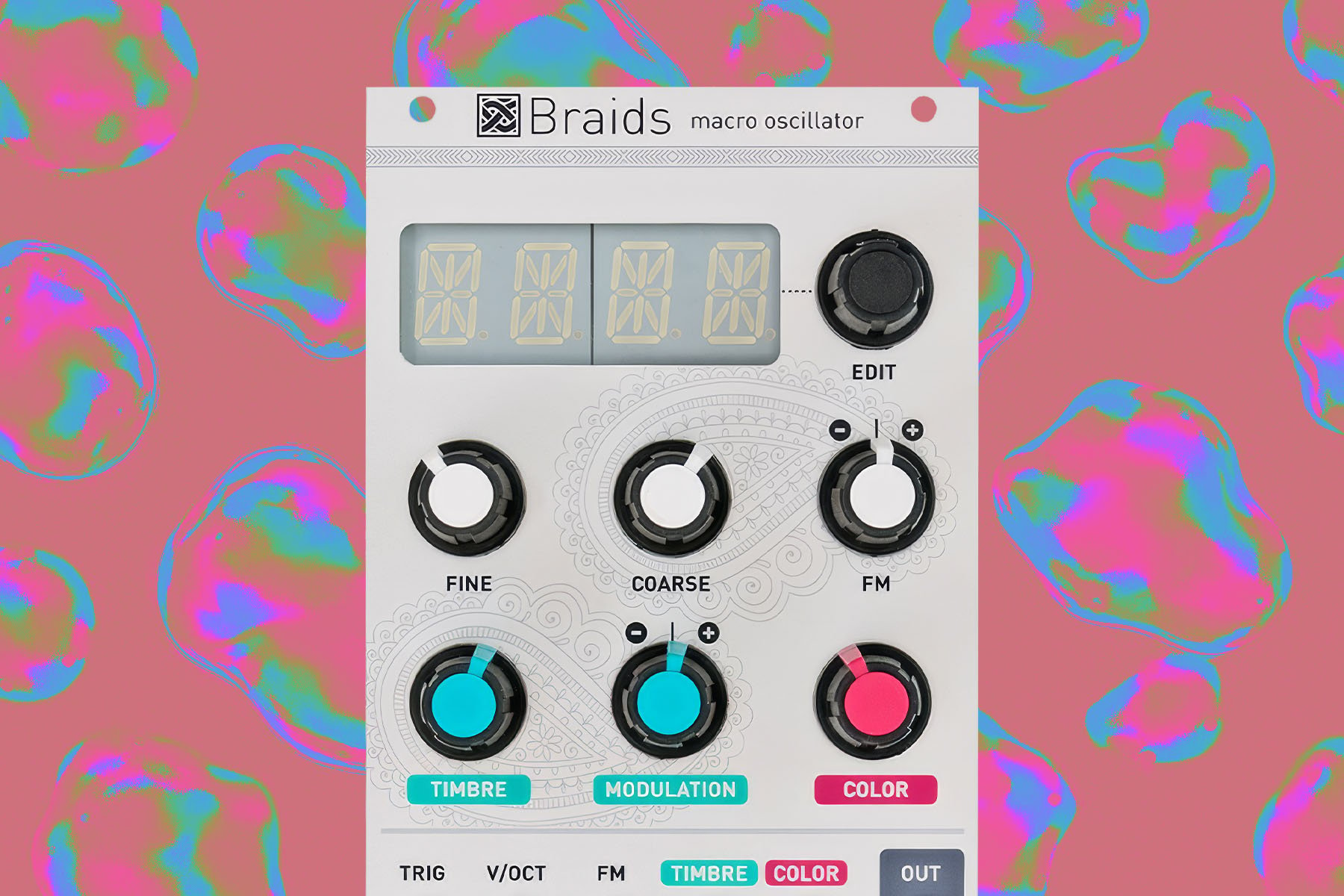

EW: How did you get into modular?

CB: It all comes back to reviews and realizing there was a world that was deeper than just drum machines and samplers. You go to NAMM, you're on the show floor, and you start to wander around and you find the synth village [Ed: At NAMM, synth companies are grouped together]. I started stumbling upon stuff that way, and I made some inroads with Pittsburgh Modular, and a couple of other companies. Pittsburgh eventually sent me a small skiff to review, like 90HP. A lot of times as a reviewer, you may be asked to review stuff that you don't know a lot about, and that's part of the process; or you may ask to review something that's interesting that you know nothing about, and that's also part of the process. I thought it was interesting, this Eurorack thing, and thought it could be something cool to incorporate with my MPC and whatever else I was using, and so I did that, and there was no turning back. That was about 2015.

EW: How did you initially incorporate it into using it with a sampler and MPC?

CB: I was using some keyboard that had CV, and I eventually learned about MIDI to CV stuff. I just kind of went through that, and initially it was not very coherent, it wasn't very good. But then I started coming across some grooves, some elements, off-the-wall sounds that I could sample and then replay in my MPC. That kind of was the beginning of that whole thing. As I was exploring that space, that rig had to go back.

EW: The Pittsburgh Modular case?

CB: Yeah. I kept it for longer than I should have, and I probably should have bought it, but I didn't have the money, so I sent it back. They were gracious. They were like, ”We like the review that you did, but you know, we don't even sell that anymore!”

EW: That’s pretty funny. How did you name the Modbap movement?

CB: The name was initially a sort of tongue and cheek way of referring to the music I’d began experimenting with MPC boom bap beats and modular synthesis. I’d been alling my style synthbap because I used lots of synthesizers in my hiphop production. So naturally when I began incorporating Modular synthesis I called it Modbap. After that I began to post clips with that annotation and it stuck and caught on.

EW: The modular community as a whole is predominantly white, which is really visible if you go to any of the conventions, meetups, or whatever. How do you feel about being a part of that community, and how do you feel the modular community is different or similar in comparison to the hip hop community?

CB: Everybody's cool. Hip hop is based on competition and competitiveness, whereas the Eurorack community is more about artsy and techie vibes, sharing and community. It's a different vibe. I don't feel any kind of weird way about being the minority in any given space that I enter. I’d love to see more diversity in that space though, and I think we are seeing that slowly but surely.

EW: It's funny you say that about the non-competitive aspect. I played in bands forever, and bands always feel like they’re in competition with each other. I don't know if it's like that in hip hop, but when I entered the modular space, people weren't out for blood, they were just there. It’s one of the things that attracted me to it. You can do something without being part of its community, so, I feel like that’s something special about the modular community that it attracts you to become involved and be a part of it.

CB: What I knew from growing up and being a part of hip hop is the battle is ever-present and synonymous with every element of hip hop. If you're a graffiti artist, you're trying to be the best and you automatically have rivals. People will throw their pieces up over your pieces, if you're tagging, your name could get crossed out. There's an automatic battle element and then you go to the DJs. When has it not been a battle? I mean, ego is a part of the thing and it's aspirational. It's from a group of disenfranchised youth who are aspiring to pull themselves up and pull themselves out and achieve, but you have to paint the picture. I think about a song like Special Ed’s ”I Got it Made.” He's literally telling you, “I got it made. I got a dog with a solid gold bone.” That song encapsulates the idea of the MC mind state, no matter what you come from, what you have, it’s still about bragging about how much better you are. So that competition, that vibe, is just natural, and that's a part of hip hop. Your audience is the other guys that are doing the same thing. Nobody wants to hear you, because naturally they're better, and so there's this constant push and pull. For me, the core of everything I do is hip hop, and I’m proud of that, but I'm also proud to be a part of the Eurorack community. It's so small. That camaraderie comes from a place of surprise, like, “Oh, you're into this super nerdy niche thing, as well?” We're automatically friends.

EW: What made you want to produce Per4mer for sale? Did you have experience designing hardware?

CB: I wanted to bring something to market of my own and there were always things that I wish I had in hand, or I’d always want things to operate or integrate a certain way. Even back in the day a friend of mine and I wanted to design a drum machine. Per4mer just so happened to be the thing that is the first thing I've designed. But in my time as a reviewer for BboyTechReport.com I made loads of suggestions and feature requests. All reviewers and testers give feedback on products that hit the market, and sometimes your feedback becomes a feature, like, “These? Yeah, I told them to do that!” I've always had ideas and thought, “They should do this, or somebody should do that”, and at some point I stopped saying somebody should do it and I started doing it.

SC: What was the initial impetus for designing Per4mer, and who did you work with to get it into production?

CB: I was using the Akai Force and my Eurorack system, and I was always sketching up stuff like, “It'd be cool if, if there was something that did this, and something that did that.” After a while, there were certain things that I wanted to do, and it really started coming together when I wanted to start performing out. I have an 18U 104HP rig, and I knew I had to have a more focused live rig. I knew that I couldn't take that huge Modbap tower out. So I pared it down to a 6U 104 and started populating that case with the core things that I would need to go out and perform my Modbap sets. As I was getting used to how I will perform these beats, how I will recall things, and how I will record on the Force and be able to pull up programs and projects to be able to perform, I started getting into effects a lot more, certain delays and reverbs and such. Then I started bringing small tabletop effects units out to play live: the Korg Kaossilator pad, the Roland SP-404, and the effects inside of the Akai Force. I tried every combination of all those things that I ever could, and as things started to settle in, I started using the SP-404 more and more. At some point after performing a few times, I took a picture and posted on social media, “This needs to be a thing in Eurorack.” Within less than five minutes, I was like, “Take that down, delete that post!” At this point, I know very well how I perform, how I do my Modbap performance sets, and so I thought about what I needed to make that come together for me. I got my pen out, started sketching up some stuff, and started formulating the idea. It just went through all these different iterations and I really started thinking about what I liked about different performance effects that I would use. I liked the idea that you could have this interface that you can interact with, using multiple effects at once, and multiple parameters at once, and you could do that physically with button presses, but you could also interact via CV. And so that idea just kind of drove that thing further and further until I had an idea that I thought was solid. I knew that if I was going to manufacture anything, I wanted to have something that hit a little left field, something that was unique and memorable, because there's a lot of boutique companies that are making stuff, and there's a lot of stuff out in the market. I wanted to stand out.

EW: When did Per4mer come out?

CB: October 10, 2020. We started development on it a year earlier, but we were talking about it maybe six months before we started development, and it was just a matter of me having the money to invest, and when to get started. The pandemic delayed all sorts of things, and it was everything I could do to pull things together to drop it before 2020 was over, and it worked out.

SC: How did you go about designing the module and figuring out the manufacturing process?

CB: I used a lot of my skills from when I owned a hip hop record label back in the early 2000s. I was the person that did all the designs, so I mocked something up that looked pretty realistic, and kind of cannibalized images of arcade buttons and different stuff, and I put it in Photoshop. I thought it was pretty crude, but it was pretty close to what the end product ended up being. We were doing a lot of activities with Modbap and we went out to ElectroDistro to talk to them. They're the guys that do Qu-Bit and 2HP. I showed them some of the performance pieces that I was using and the mock up and tech specs. We had some good conversations and it just kind of blossomed from there. They liked what I was doing, and so I hired them to do the development with me, and I kind of found a family. I love that about Eurorack. There's something to be said for building relationships with people, because before I thought about doing my own modules, or anything, Andrew [Ikenberry] from Qu-Bit was one of the guests that came on to my BeatPPL podcast, and it was real cool. I had BboyTechReport and he would send me stuff to review and post the news for things. And we’d see each other at NAMM, and there was a rapport that was building, the same kind of thing [I had] with other manufacturers like Pittsburgh Modular, Studio Electronics and Noise Engineering, and you start to realize, I'm kind of making friends. I've been doing BboyTechReport for a long time, and I realized that I've kind of been mentored without realizing it. I've been beta testing, and talking to the actual developers of some of the most well known equipment and software that's out there, learning all these different things, so when I decided this is what I wanted to do, I already knew that I should go talk to this or that person, and it worked out well. I look at people that I look up to, like Roger Linn and Glen Darcey, they're the guys who know enough to make sure that it gets done right. Those guys gave me the confidence to say, “I think I can do this, if I just align myself with the right people and outsource what's proper to outsource, and do the stuff that I can do.”

EW: So you’ve got Per4mer, and a module that just came out, Osiris. What’s the vision that you have for the company?

CB: I design instruments based largely on what I’ve experienced as an artist and what I need and want as an artist. I have this sys‐ tem that I'm building towards, and the Per4mer was kind of the first thing out of that gate. The new module, Osiris is a bi-fidelity wavetable oscillator. I'd read that Osiris was the God of many things, but one of which is the God of water and waves, and it made sense.

SC: And now Osiris is the god of wavetable modules.

CB: Exactly. I did this in collaboration with Ess Mattisson who did the Digitone and Model:Cycles for Elektron, and so we worked together on this.

EW: Why did you want to work together? What was it about collaborating with him?

CB: I knew I had this design and that I wanted to work with somebody to help me bring it to life. I had a mock up and tech specs and all of the trimmings with some very specific ideas about how it would operate—the processing which became the timbre modes, the sub osc and how it would operate etc. I knew that Ess would be the right person to hire to develop the synth voice behind my design. I sort of view things in my journey of development like this...I have an associate's degree in electronics, but I didn't go into electronics, I went into computer technology. That's a different sort of world. I can dust off those [electronics] skills, but do I want to take two years to design every module? No. I like to collaborate with people and hire people to do the things that I am not great at. That’s just good business in my eyes.

EW: You talked about making Per4mer and Osiris because you wanted to make your performance rig smaller. Have you been able to do that? What did you finally pare it down to?

CB: What I typically take out is a 60 HP Intellijel case. I have a Per4mer, an output module, a filter, voices, and modulation and stuff. I realized that I liked the idea of having a small clean system like this with my drum machine, and so I want to design a system that complements how I like to perform, something that is big enough where you feel like you actually have a system, but compact and versatile, more than meets the eye.

EW: On your website, you have a list of values, like culture, experimentation, and community. It's obvious how much community means to you.

CB: Community is huge to me. Like I said, when I went from a solo act, promoting my music, to more of a band, I noticed progress was made more than when it was just me. There's power in numbers, and things progress in a different way every time I see more of a “We” mentality than a “Me” mentality. There's a Modbap compilation out now on Beatppl, as a label, called Diggin’ In The Wires. It’s a two-LP record that I think is a really special project, and not just because it’s a project that I put together. It's almost twenty different people making this music that I thought only I was making and we were able to come together and say, “Yes. This is Modbap.” That I can put that together and pull everybody together, it feels special, like a movement. So community is huge to me. In BboyTechReport, I serve the community of beat makers and synthesists, and companies will come to me and say, “We want you to do this, to talk to your audience.” And in talking to my audience, I'm just talking to the community.

SC: Looking back on your progression from hip hop artist to Eurorack module designer, are there things that surprise you about that journey?

The transition from artist/emcee to producer to live beats performance to instrument designer and manufacturer...all of it is a surprise. This was not the plan, but I’ve just allowed myself to trust what I enjoy doing, and it turns out I’ve enjoyed all of it. Every previous thing has informed the next thing.

Thanks to Waveform Magazine

Waveform is a quarterly print magazine about sound synthesis and those who inhabit that world. Check out Waveform on our site, or head to their own website to subscribe, grab some swag, DIY projects, and more!