What associations spring to mind when you think of "chaos"? Disorder, mess, disarray, confusion, randomness, and noise—these terms likely resonate with many people. Our customary interpretation of the word supports attributing a chaotic behavior to a wide array of situations where discerning an orderly pattern proves challenging. However, since the mid-20th century, a burgeoning science—chaos theory—has begun to uncover the deterministic order within systems previously deemed disorganized and volatile. Indeed, there can be order within perceived chaos. The insights gained in this field over recent decades have profoundly reshaped our comprehension and engagement with the world.

Interestingly, chaos theory has also sparked a wave of innovative approaches in various artistic domains. That said, it is important to acknowledge that on some intuitive, subconscious level, arts have long been a forerunner in recognizing and even harnessing chaos's creative potential. For example, ancient Chinese landscape painters portrayed nature as a dynamic, ever-changing entity—naturally growing and spontaneously changing. Islamic art and architecture also exhibit similar recognition of complexity, with artists employing mathematical models to multiply and distribute a small geometric element into massive fractal-like patterns. And of course, the multiple strains of avant-garde and experimental music that emerged in the last two centuries incorporated chaos into the practices to various degrees.

Our focus in this article gravitates in particular toward the application of chaotic systems in sound synthesis, music composition, and production. Chaotic sound synthesis encompasses a variety of approaches. Some draw directly from chaos theory's scientific principles, while others are inspired by their inherent design features, exhibiting attributes of dynamical systems, emergent complexity, and sensitivity to initial conditions. This form of synthesis isn't a standalone category, but intersects with other synthesis methods, such as subtractive, additive, granular, and physical modeling synthesis, along with circuit-bending and no-input mixing. Furthermore, chaotic systems find application at the macro level of composition, offering innovative tools for algorithmic and generative frameworks.

The primary goal of this article is to elucidate the wide-ranging applications of chaotic sound synthesis and underscore its significance in the field. We'll start by exploring the foundational theories of chaos and essential concepts pivotal for working with chaotic systems. Subsequently, we'll weave in historical perspectives to bolster the connection between musical applications, other disciplines, and tangible world scenarios. Following that, we'll examine some prevalent techniques and algorithmic models, leading to a discussion on various creative implementations. Throughout the article, I'll highlight key musical instruments and instrument designers who have embraced chaos theory principles. Finally, I will discuss a few ways one can engage with chaotic sound synthesis, and illustrate practical steps for artists and composers to incorporate these techniques into their work. The aim is to empower readers with the knowledge to not just understand, but also creatively apply chaotic sound synthesis in their artistic endeavors, fostering a deeper connection between theoretical principles and practical application in music and sound art.

What Is Chaos? A Bit Of Theory

Recall a moment when you paused to listen to the intricate rhythms of falling raindrops, the immersive tides of ocean waves, or a lively bird chatter. Chaos is not a mere scientific concept, but an actual orchestrator of the natural world. The dynamic complexity that accompanies chaotic systems is often perceived as randomness, but this couldn't be further from the truth. So what sets chaos apart from randomness? True randomness is about events that follow no specific rules, remaining unpredictable. Chaos, on the other hand, emerges from deterministic systems. These systems adhere to fixed rules—meaning that, if we know the input, we should be able to predict the output. Yet, when complexity and sensitivity to initial conditions intertwine, predicting the long-term behavior of chaotic systems becomes a formidable challenge.

Imagine holding a pendulum, feeling its weight in your hand. As you release it, the pendulum starts to swing back and forth with predictable grace. But what if you attach a second pendulum to the first? This simple change, a repetition really, instantly plunges us into the realm of chaos. The movements of the double pendulum defy expectations. Dancing between harmonious rhythms and erratic jumps—what is happening here? The coupling of pendulums creates a dynamic system where at any given point in time the two pendulums affect each other, as well as being affected by external forces. When you set the system off, the initial conditions—lengths of each of the pendulum's arms, masses of the bobs, initial angle, and initial angular velocity (aka speed)—determine whether the double pendulum will subtly wobble with discernable periodicity or start capriciously drawing random squiggles in the air.

Since the double pendulum is a deterministic system, what guides the complexity of its chaotic behavior? In the midst of what appears to be an erratic motion, attractors serve as unseen guides, shaping the system's long-term behavior despite its short-term unpredictability. These attractors are not just abstract mathematical entities; they are the underlying order within the chaos, the patterns that emerge from seeming randomness. Attractors can be seen as the system's endpoints. Mapped in a chaotic system's phase space, they are the destination points that represent all possible states of the pendulum bars. A simple pendulum has a fixed-point attractor, meaning that it eventually comes to a single resting point. The attractor in the double pendulum is much more complex: it is what is known as a strange attractor, representing a whole set of possible states that the system can oscillate between, creating fractal-like patterns.

Another concept that is related, and important to understand for a general overview of chaos theory is the Lyapunov exponent, a measure that quantifies the rate of separation of infinitesimally close trajectories. In simpler terms, it tells us how quickly predictability is lost in a system. A positive Lyapunov exponent indicates chaos, signifying that small differences in initial conditions grow exponentially over time, leading to vastly different outcomes. A negative exponent indicates a more stable state.

We should also touch upon entropy, a concept for measuring the amount of uncertainty or disorder within a system. In a dynamical system, entropy can be related to a rate at which the initial signal is lost over time. Higher entropy implies an increased degree of unpredictability and disorder within the system.

[Above: an original Buchla 259, part of the 200 system housed at the University of Victoria, BC, Canada.]

Ok, Let's shift the discussion toward sound for a minute. A so-called "complex oscillator," a popular Buchla-inspired sound synthesis architecture, typically features two oscillators that can be set to cross-modulate the frequency and/or amplitude of one another. At mild settings, the oscillators converge into unique and harmonically rich timbres. As you increase the amount of cross-modulation, and balance the frequency settings, the effect becomes increasingly more pronounced—until it reaches a point where the tone disintegrates into a recognizably chaotic intermingling of noise bursts, pulsing rhythms, sputters, and drones. Not unlike the double-pendulum example, a complex oscillator follows a strict set of rules, yet due to the internal feedback loop at a certain point, its output becomes unstable and unpredictable. Altering the initial conditions (aka the parameters of the two-oscillator system)—even only slightly—may have a major impact on the sound.

A Very Brief History Of Chaos Theory

Tracing the lineage of chaotic sound synthesis feels paradoxical, as its essence diverges sharply from concrete synthesis methodologies like subtractive synthesis, AM, FM, or granular synthesis. Chaotic sound synthesis is an eclectic amalgamation of principles from chaos theory, sound synthesis, and musical composition, melded together in diverse ways by a plethora of researchers, composers, and sound artists since the twilight of the 20th century. To unearth the roots of this complex field, we must journey back to the inception of chaos theory itself—a story as rich in serendipity as it is in intellectual discovery.

The Three-Body Problem, while renowned as a science fiction novel by Chinese author Liu Cixin, also refers to a real challenge in physics and celestial mechanics. The problem was articulated by the 19th-century French mathematician and physicist Henri Poincaré. Unlike the relatively straightforward Two-Body Problem, which models two celestial bodies interacting in isolation, the Three-Body Problem logically introduces a third body, exponentially complicating the dynamics. Poincaré's foray into this problem, motivated by a competition hosted by King Oscar II of Sweden in 1889, led to an epochal revelation. Though an error was initially spotted in his submission, Poincaré's subsequent scrutiny unraveled the profound insight that the system's sensitivity to initial conditions thwarted any attempt at long-term predictability, thereby sowing the seeds for modern chaos theory.

Fast forward to the mid-20th century, where the narrative of chaos theory unfolds its next chapter with Edward Lorenz, a mathematician turned meteorologist. In the early 1960s, Lorenz's computer model simulations at MIT led to an accidental discovery. By restarting a simulation with slightly rounded data, he observed a drastically different weather pattern, unveiling the sensitivity of nonlinear dynamical systems to initial conditions. Lorenz's subsequent formulation of three non-linear equations, visualized as the Lorenz attractor, revealed a mesmerizing pattern resembling butterfly wings, symbolizing the interconnectedness of chaotic systems.

Despite the transformative implications of Lorenz's work, his revelations, encapsulated in the seminal paper "Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow," initially received a lukewarm reception from the scientific community. The broad implications of chaos theory only began to crystallize as computational advancements in the 1970s and 1980s democratized the exploration of complex systems. Lorenz's conceptualization of the "butterfly effect" during a 1972 lecture not only popularized chaos theory but also infused it into the zeitgeist, influencing fields as disparate as climate science and popular culture.

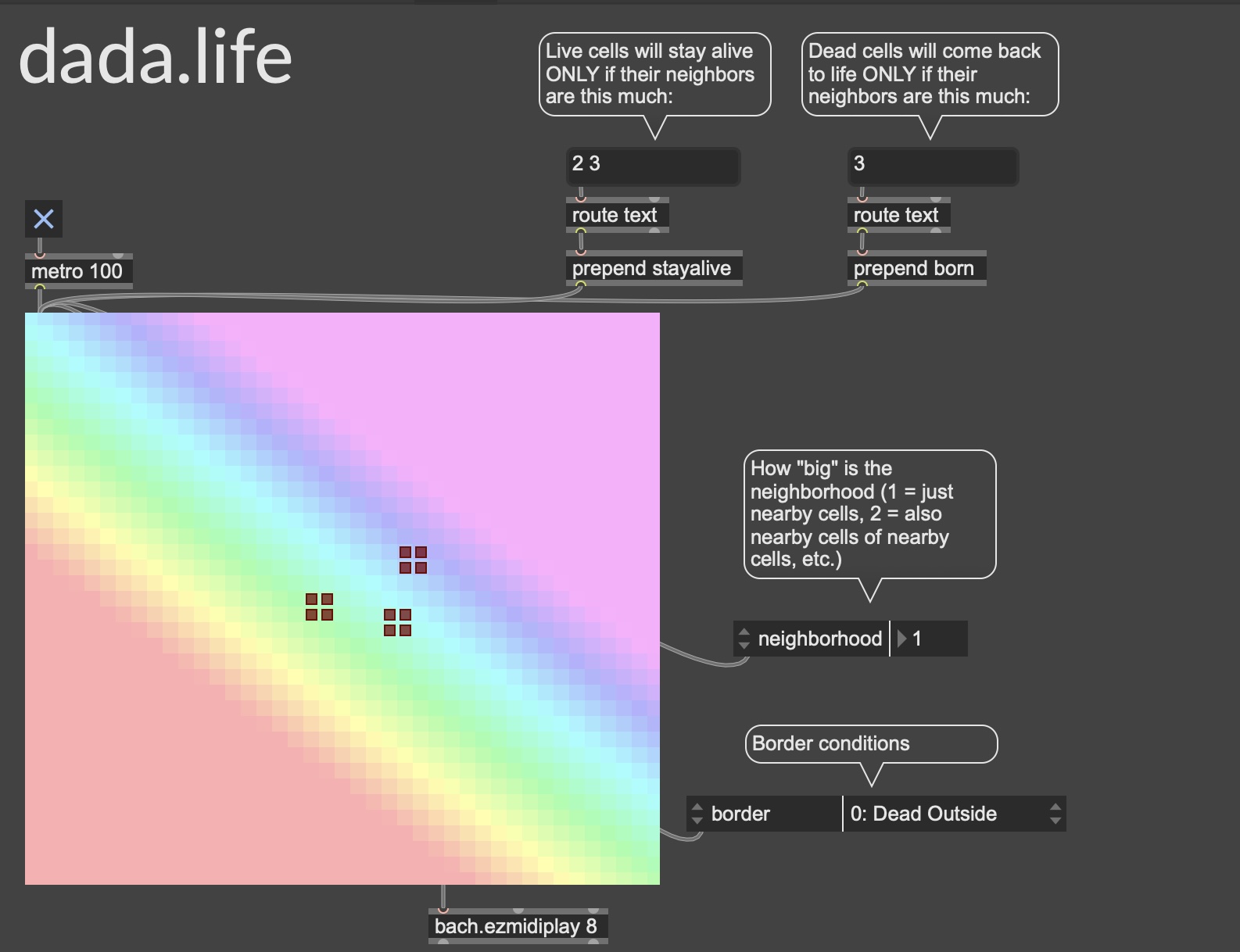

[An implementation of Conway's Game of Life in Max/MSP.]

Alternative to the continuous systems explored by Poincaré and Lorenz, the luminary polymath John von Neumann delved into discrete systems, conceiving cellular automata in the 1940s. These mathematical models, demonstrating how simple rules can generate complex patterns, further expanded chaos theory's scope. Von Neumann's ideas, popularized through John Conway's Game of Life, showcased the emergence of complexity from simplicity, echoing the core principles of chaos theory.

The evolution of chaos theory continued with seminal contributions from Otto E. Rössler, Benoit Mandelbrot, and Mitchell Feigenbaum, enriching our comprehension of chaotic dynamics, fractal geometry, and the nuances of system behavior. The publication of James Gleick's "Chaos: Making a New Science" in 1987 marked a pivotal moment, distilling the essence of chaos theory for a wider audience and underscoring its relevance across a spectrum of disciplines.

A Brief History Of Chaotic Sound Synthesis

With this backdrop, chaotic sound synthesis takes on new depth, embodying the interplay of determinism and unpredictability. In my explorations, I've consistently observed that music and sound uniquely echo natural phenomena. My experience is far from unique, countless musicians, composers, and listeners throughout the ages and cultures have experienced and utilized it. The way sound transitions affect us is profound: emotionally through direct listening, physically as we feel the vibrations course through our bodies at high intensities, and intellectually as we visualize audio signals through spectrograms and oscilloscopes, gaining insights into the mathematical and geometrical dimensions of sound. Chaotic sound synthesis as such not only provides us with a framework for generating unique sounds and music, but it also allows us to connect with something far more ancient, and universal, illustrating the profound connection between art, nature, and science.

This deep intertwining of science and music isn't a recent phenomenon, but a historical constant—mirrored in the symbiosis between chaos theory and electronic sound. The genesis of this relationship involves various catalysts. Before chaos theory was formally established, artists like John Cage and Iannis Xenakis were already probing the boundaries of sound using chance operations and stochastic methods, laying groundwork that resonated with the later principles of chaos theory. Cage's use of the I-Ching and Xenakis's application of mathematical models in compositions like Metastaseis and Pithoprakta exemplify early intersections of randomness and structured musical creation.

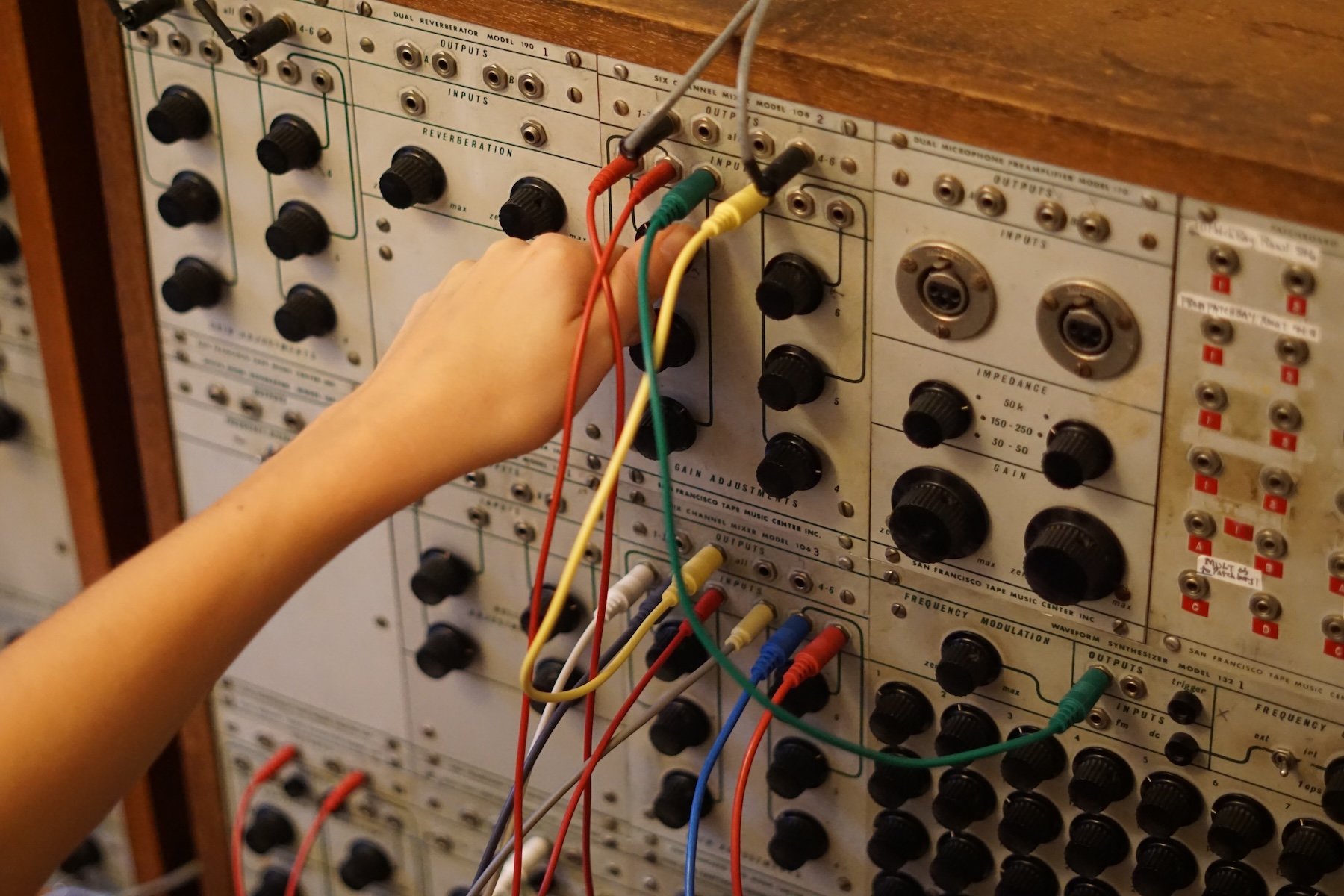

The advent of the synthesizer marked a pivotal era in music, offering composers unprecedented control over sound creation. This new tool aligned perfectly with the expanding definitions of musical sound and the composer's role. Analog computers, used by physicists and mathematicians to model dynamical systems, bear a resemblance to modular synthesizers. These instruments, with their complex web of cables, embody chaos visually and sonically, allowing real-time auditory exploration of mathematical operations.

[Above: 144 and 158 dual oscillators in the original Buchla 100 system at Mills College. Image courtesy of Sarah Belle Reid.]

Synthesizer pioneers like Robert Moog, Donald Buchla, and Serge Tcherepnin responded to artistic curiosity with innovative instruments, subtly incorporating chaotic principles. Buchla's early systems, for example, featured modules like the 144 Dual Square Wave Generator and the 158 Dual Sine/Sawtooth Generator, precursors to complex oscillators facilitating chaotic synthesis. These systems, with their sample-and-hold circuits, noise sources, random voltage generators, and importantly, open and flexible patching, laid the groundwork for unpredictable sonic exploration.

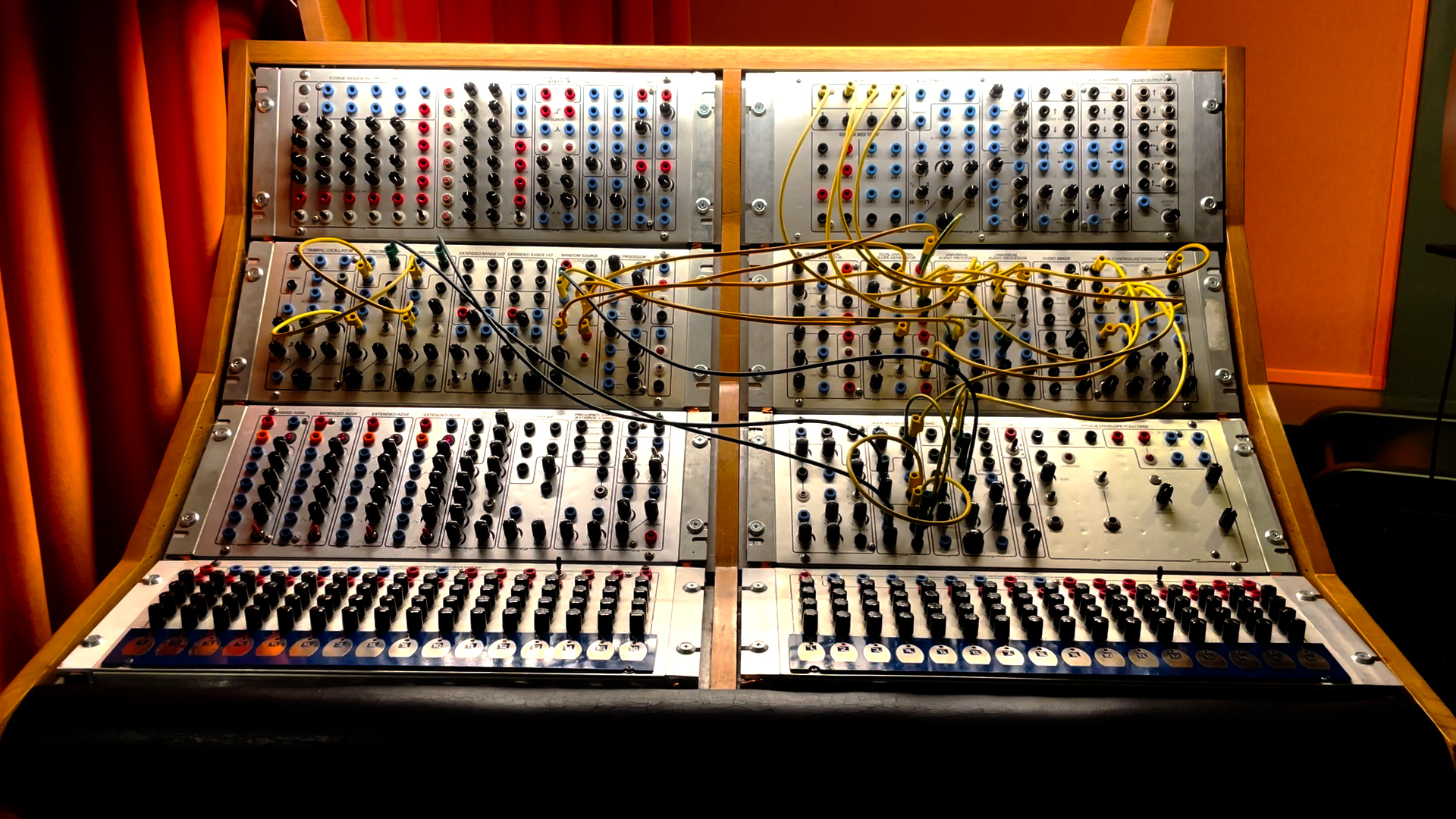

[Detail of the Serge Modular Music System at Elektronmusikstudion (EMS) in Stockholm, Sweden.]

In part responding to demand for more affordable synthesizers, Serge Tcherepnin managed to create one of the most flexible and customizable modular synth systems available. With no embedded distinction between audio and modulation signals and designed in harmony with the philosophy of patch-programmability,, the Serge Modular Music System became the epitome of an analog sound computer capable of a wide array of complex chaotic behaviors. Classic modules, like the Dual Universal Slope Generator and the Smooth/Stepped Generator, can be reconfigured in myriad ways to foster chaotic audio and/or control signals.

The Blippoo Box, a chaotic instrument designed by the late Rob Hordijk.

The Blippoo Box, a chaotic instrument designed by the late Rob Hordijk.

In practice, chaotic sound synthesis has been accessible to synthesizer users since the inception of this new instrument. We haven't even delved into sub-culture movements like circuit-bending and no-input mixing, which have their own unique relationships with chaos. However, instruments explicitly designed around chaos theory principles began to emerge only in the late '90s to early '00s. A prominent adopter of these principles is Rob Hordijk, creator of beloved instruments like the Blippoo Box, Benjolin, and the robust Hordijk modular system. His designs maintain the openness for indiscriminate intermodulation found in Serge systems, but with a more focused approach to chaos. A key feature in Hordijk's instruments is the rungler—a complex voltage generator created by cross-modulating a pair of oscillators through an analog shift register. When set to modulate oscillator pitch and/or filter cutoff frequency, as in the Benjolin, the rungler generates an ever-evolving stream of extreme and subtly changing musical patterns.

Chaotic systems have also been extensively explored in digital and software instruments over the past few decades. For instance, chaotic behavior is often implemented in granular synthesis to distribute sound particles. Curtis Roads, in his seminal work Microsound (2001), refers to examples like the cellular-automata-based Chaosynth (1998) by Eduardo Reck Miranda. The cellular automaton concept and its derivatives, such as Conway's Game Of Life, have been extensively explored in music-making, particularly in various generative sequencers.

In the contemporary world of synthesizers, sound design, and music creation, chaos increasingly occupies a central role in discussions. Peter Blasser, like Hordijk but in a distinct manner, places chaotic behavior at the core of his instrument designs. Vlad Kreimer's designs at Soma Laboratory also embody a fascination with chaotic behavior, with Pulsar-23, Lyra-8, and Ornament-8 as notable examples. In the Eurorack realm, the array of chaos-infused modules is vast and continuously expanding. Additionally, modern audio programming environments like Max/MSP, Supercollider, Pure Data, Reaktor, and others provide expansive frameworks for delving into chaotic sound synthesis. For those less inclined to program, independent software developers like Dillon Bastan offer a plethora of finely tuned chaos-inspired instruments, effects, and performance tools.

Tools and Techniques

Now that we've delved into the significant aspects of the history of chaotic sound synthesis, it's time to explore the "how" aspect of this riveting subject. If you're captivated by the idea and wish to integrate chaotic systems into your creative process, you might wonder where to begin. What tools and techniques can aid in creating and interacting with complex systems? And is a deep understanding of the mathematics behind chaotic systems necessary for their creative use and comprehension? Let's first address this question.

As I see it, there are two primary modes of engagement with chaotic sound synthesis, each catering to different purposes and interaction styles. One approach is more general and intuitive, not requiring in-depth knowledge of specific chaotic algorithms but a broad understanding of interactive systems, making it suitable for analog synthesizers. The other approach involves applying chaotic algorithms directly into audio or control voltage domains, where computers or specialized synth modules, due to their precision, are more effective. These approaches are not mutually exclusive, but outlining them clarifies your options.

Feedback is central to chaotic systems, occurring at various stages but essential for the sensitive interplay between past and future system behaviors. You can start exploring chaotics by creating feedback-based setups. Even with basic equipment like an analog mixer and a few cables, you can delve into no-input-mixing, discovering erratic soundscapes.

For more control over sound and behavior, modular synthesizers offer numerous possibilities. They allow you to implement chaotic behavior in sound generation and control. Begin with simple cross-modulation of frequencies and/or amplitudes between two oscillators, reflecting the complex oscillator concept. Extend this principle to other functions, like having two or more envelope generators modify the rise and fall parameters of one another in a circle, or multiple sequencer tracks affecting the behavior of one another. From there, depending on the context and what you are trying to achieve, you can add complexity by adding other functions and processes into the mix, as well as increasing the number of feedback stages, and the relationships between the elements in the system. For example, when deciding on the structure of the system, you can explore a variety of common communication flows for feedback arrangements: one-to-one, one-to-many, many-to-one, and finally many-to-many.

Carefully considering the sensitivity-dependence aspect is crucial for two reasons. One is of course control, which means that it is essential to make sure that you have the finest degree of control over the most sensitive parameters, in particular the depth and direction of the modulation signals. Second, because feedback paths are unpredictable, and quickly can get out of control, especially in situations when feedback is generated in the audio path or acoustically i.e. no-input-mixing, it is wise to be mindful of volume spikes, and always approach it carefully.

Another intuitive way to engage with chaotic systems is using instruments with built-in chaotic features. We've mentioned notable chaos-inspired synth designers previously. Hordijk's Benjolin is an excellent entry point into chaos, available in various formats today. Instruments from Ciat-Lonbarde and Meng Qi also feature chaotic elements, each with a unique design perspective. Eurorack universe is full of chaos-imbued modules. Make Noise, Nonlinearcircuits, Schlappi Engineering, Blasser's Ieaskul F. Mobenthey, omiindustriies, and many others tailor all or some of their tools for non-linear behavior. The vastly popular Make Noise Maths alone is capable of providing a rich source of chaotic signals.

Finally, if you decide to delve deeper into the science behind chaotic systems and explore the implementation of existing algorithms, one of the best approaches is through the audio programming environments we've discussed earlier. Similar to a modular synthesizer, such software tools allow you to construct complex systems from smaller components. These blocks can be much smaller and utilitarian, offering finer control and scalability. For instance, you can precisely model Lorenz or any other attractor, and use it for modulation or sound generation. You can fashion out or use one of the existing cellular-automata-based sequencers to create ever-evolving generative music.

As you continue exploring chaotic sound synthesis, you may want to learn more about the subject, and in such a case numerous resources are available. The Complexity Explorer project from the Santa Fe Institute provides a range of courses on chaos-related topics, suitable for both beginner and advanced learners. More specifically related to sound, Generating Sound and Organizing Time Book 1, a tutorial book by Graham Wakefield and Gregory Taylor from Cycling 74, includes a chapter dedicated to crafting chaotic systems using the Max/MSP gen~ environment. For further insights, refer to our recent interview with Graham Wakefield.

Another noteworthy resource is the article "Chaotic Sound Synthesis" by aerospace engineer and musician Dan Slater, published in the Computer Music Journal in 1998. Slater's work investigates how chaotic and fractal equations can be employed to produce innovative and artistically compelling sounds and compositions. He particularly focuses on chaotic sound synthesis methods, emphasizing analog techniques and their application in electronic music. Slater also touches on the relatively recent and fascinating concepts of hyperchaos. Unlike typical chaotic systems with a single positive Lyapunov exponent, hyperchaotic systems boast multiple positive Lyapunov exponents. This characteristic introduces an additional layer of complexity, as the system's trajectories diverge in several directions simultaneously, leading to an even richer, more unpredictable behavior. Hyperchaos stretches the boundaries of what we understand about chaotic systems, offering new avenues for exploration and creative experimentation.

Conclusion

Chaotic sound synthesis may appear as a challenging topic for several reasons. Its multifaceted nature means it intersects with—and sometimes goes beyond—traditional synthesis techniques, intertwining with advanced concepts from physics and mathematics. Whether this is advantageous or not depends on your perspective, and level of comfort with these fields. The sonic character of chaotic systems also presents a dichotomy: while it's possible to achieve conventionally musical patterns, embracing the unpredictable, potentially noisy, and disorienting aspects of chaotic synthesis is essential for finding value in it for your creative process. This method leans more towards challenging standard musical structures rather than conforming to them.

As we have traversed through the history of the science and the synthesis method, I hope that I was able to translate the science-related information to you as clearly as possible, yet I also hope that I have provided a compelling and inspiring framework for you to engage with the chaotic method regardless of your comfort with the scientific concepts. Be it through no-input mixing, modular synthesis, or cutting-edge programming environments, I wish for this article to be a helpful tool for artists, equipping them with an array of tools, and concepts to navigate the ever-evolving labyrinth of chaotic sound. After all, chaos is a natural and pervasive phenomenon, and the odyssey through the chaos isn't merely about grasping a theoretical concept, it's an embrace of the unpredictable nature of our world, a quest to discover harmony and meaning in seeming randomness, continually reshaping the musical and sonic landscape.