In the vast landscape of synthesizer design, few creators have carved as distinctive and inventive a niche as Peter Blasser. Known for producing some of the most visually arresting and sonically adventurous electronic instruments available today, Blasser exquisitely blends artistry and circuitry, philosophy and praxis. While commonly associated with the renowned synth brand Ciat-Lonbarde, his repertoire extends far beyond, as he masterfully explores diverse facets of what a synthesizer can truly be. For further insights into his eclectic portfolio, we recommend our recent article Hello Shnth: A Timbered Enigma in the World of Synthesizers.

A short while ago we had the fortunate opportunity to catch up with the inventor at his new headquarters, Patch Point Berlin. There, at his basement workshop, Peter was meticulously perfecting another custom build of his enigmatic Shtar. As he diligently filed the frets, strung and tuned the instrument, we indulged in an expansive dialogue about his work, traversing topics such as his relocation to Germany, his ethos towards instrument creation, current and forthcoming projects, inspirations and challenges, the significance of community, and the art of transmitting knowledge.

Balancing on the edge of tradition and innovation, Peter offers a profound perspective on the trajectory and latent possibilities of the field. So, join us as we explore the intricate interplay of thought and craftsmanship that Peter Blasser so strongly embodies.

Interview with Peter Blasser

Eldar Tagi: Thank you, Peter, for talking with me today. Now, I'd like to start with your relocation to Berlin. What stirred you toward this move?

Peter Blasser: So, moving to Germany? Well, my wife had this idea for some time. Then, I met Darrin (Patch Point) and he told me his story. In Portland, I was working all by myself, making and selling every single instrument. I was working from my backyard, a setting I initially thought was good but it wasn't really. I had to work and parent simultaneously, and that was not the best situation for me. Back in Chicago, the first personal rule that I ever made was that you don't sleep in your workshop. So whenever I break this rule, I know that something is not right. I tried to work with stores, but the best deal I could get was only retaining 70% of the sales while doing the same amount of work per instrument. This didn't work for me. So, I said "no" to all the stores.

Then Darrin came along, and somehow he seemed to intuitively know what the situation was. He had this vision of a "banana-only" synth store, which sounded simple but was actually quite visionary. And it felt like he had done his homework. Bringing some historical context, if you look at how it went for Serge and Buchla you see some parallels. Buchla lived in his workshop, and while Serge made a lot of kits, he also did a lot of work himself, building instruments to order. This is something that I was doing, and I think Darrin knew this. He understood that if you are producing, say non-Eurorack instruments, you end up being a loner. Being a loner is good philosophically because you can realize this radical vision. But then you end up doing all the work yourself.

The Patch Point Berlin storefront.

The Patch Point Berlin storefront.

Before we even started working, I asked Darrin if he had his own workshop. I sent him some circuit boards. Then I came to Berlin, and we did a Tocante workshop together. From there, I started sending him wood, and circuit boards from the US. That was the first stage of our collaboration.

I continued working with Darrin because he kept on solving problems. He established a connection with the Bastl crew in the Czech Republic who had a CNC machine. So I came over, and we went to Brno, which was a lot of fun. I spent two days of hard work setting up the machine, but that meant that I could delegate some of the woodworking.

Then things aligned, and we decided to move. Ayako wanted to move to Berlin for its art and culture, and we thought it would be a good chance for our kids to learn German. After moving, Darrin and I started setting up our own workshop here. Darren was all in, which I hadn't seen from any other store before.

We invested a lot in the woodshop, which is now running well. Unlike in Portland where I was the only person running one machine, we now have multiple people operating eight machines. It's more efficient that way, having a full workshop with several people involved.

ET: I see. And do you feel like scaling up production like this also serves well for disseminating your knowledge and practice?

PB: Yes, it helps. I have been packing up all the information that people who build my instruments need to know, and I've been streamlining it so there are no unnecessary silly things that they need to take into account while doing the work. This process makes me contemplate things that I want to teach people versus things I don't have to teach people. It is much easier to add a line in the CNC code so that it takes care of all the small nuances, instead of having them be memorized by hand.

ET: Your most recent project is Peterlin—a re-imagining of one of Rob Hordijk's famous designs, the Benjolin. What inspired you to do it, considering your usual approach of creating original instruments?

PB: I was always excited about the idea of doing a project based on Rob's work. Working on this Benjolin felt almost like an anthropological project of sorts. I was really digging into another person's intentions. It was new territory for me, recreating or copying a circuit like this. I've never done this before. So what I did, in the end, is a kind of remix. I even replaced the chips Rob used with the ones I was accustomed to. The entire thing is completely redone, including the layout.

Rob's original design is based on a grid, which I really respect, and that is what I started with. But I wanted to reduce the circuit into a small square. Partly because I wanted to utilize all of the scrap wood pieces around the shop, but also if a synthesizer has extra room on a circuit board, I am going to shrink it. I do that. A circuit board is an expensive and environmentally costly material, and I don't want to waste it.

Also, I like wood. I want to see a thousand or two-thousand-year-old synth case. And I think it will still be there. But it will be nice and loose. I think that is cool. And it's always possible to create a new case. What's more, my synths are designed without any decaying components, like electrolytic capacitors. Technically, they are supposed to last forever.

By the way, I've made the files open source, though they are still cluttered and need to be edited. There is a whole philosophy behind coding these.

Moreover, we're currently working on some exciting add-ons for the Benjolin, like a Deerhorn. It's essentially a CV theremin, one on each side.

ET: Oh, exciting! Is this blend of the Peterlin and Deerhorn?

PB: It is not the Deerhorn synthesizer, just a theremin controller. Some of the original Benjolins had an infrared controller, and we're trying to bring that back.

But as I've said it is more of a remix. I'm experimenting with this gold leaf antenna. The original Deerhorn uses a circuit board as the antenna, which is cool but expensive and involves more circuit board material, which again is an environmental thing. The gold leaf can work just as well. So I am really excited about this development.

ET: Very cool! Are there any other extensions in development?

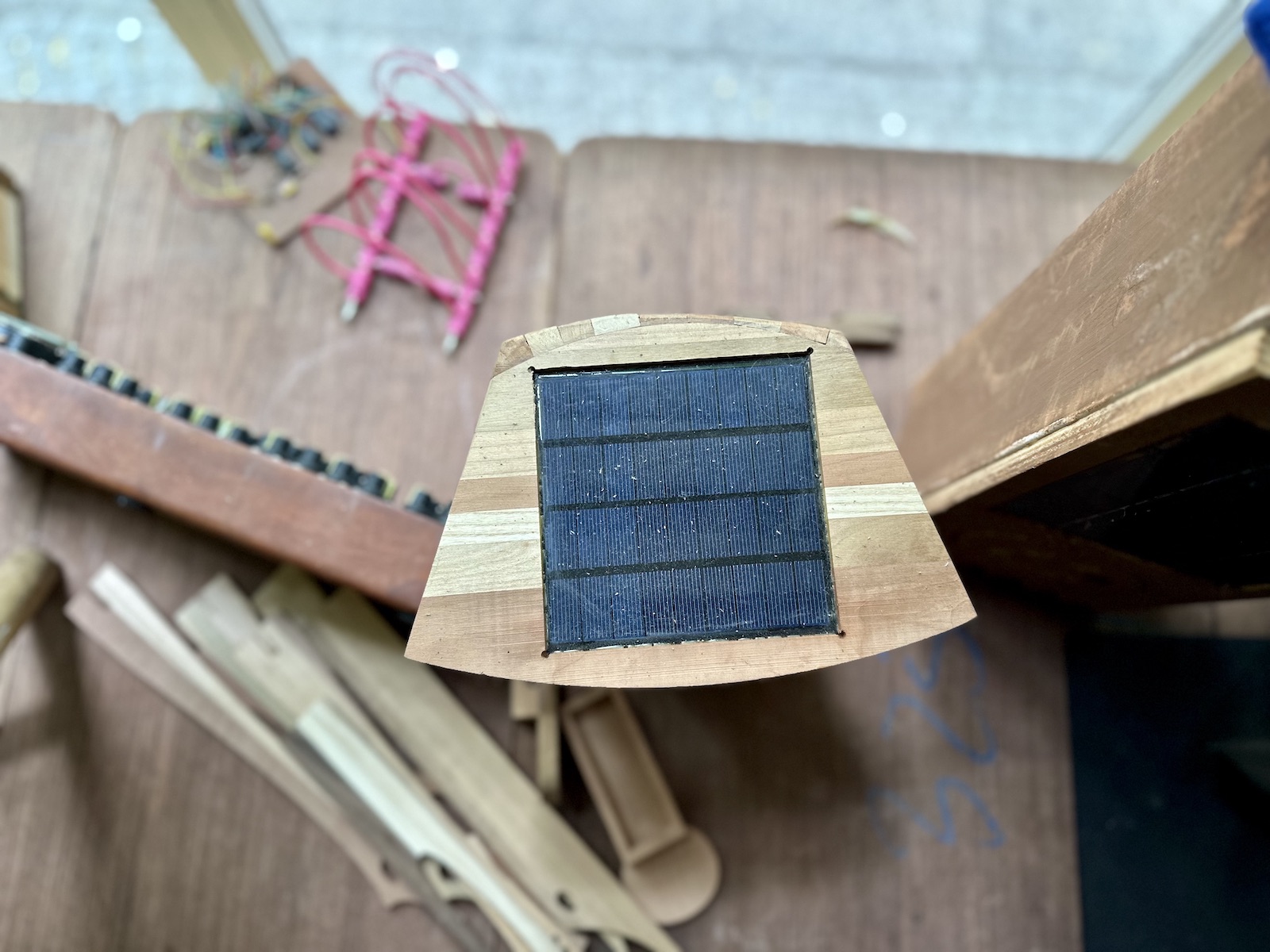

PB: Yeah, there are actually a number of Benjolin extensions that I'm working on. One project I'm particularly excited about is a solar-powered Benjolin. This idea behind it actually started before Rob passed away, when I was operating a woodshop in my own infield. However having people around who are doing the work, afforded me time to revisit some of my older ideas, such as this one.

The design incorporates a case I've been making for a long time, which has this unique shape that I really like. It is kind of a pod with non-parallel ends. It is easy to install things inside of it, and the shape also lends something to the playing experience. It's also aesthetically pleasing.

The original design didn't include a solar panel. However, over the last year, I figured out how to represent the design mathematically and code it. Now, the entire process is coded, and I've been experimenting with using this shape for solar sounders—these simple sound art objects.

However, the size of the case was much larger than the circuits in it. So I've decided that I want to push the idea further and have an actual synthesizer inside with knobs and everything. So it popped into my head to do a Benjolin. It seems to be a perfect fit. The question now is how it will perform with solar power, which I haven't fully tested yet. I am really excited to see what happens. So yeah, this is also one of the extensions to the Benjolin idea.

ET: Before you started working on the Benjolin project, did you communicate your plans to Rob?

PB: So what had happened was before Rob passed away, we had been contacting him regarding our intent of doing the Benjolin. I had made Benjolins with him before, and I had helped him to organize workshops. So I wrote him all these emails, and I said that I would make it exactly the way he did, including the case. But he never got back to me.

Then he passed away, and I know that silence has meaning—it is also a way to communicate. So when Darrin and I were trying to communicate with him, asking whether we could use his design or whether we could license it, he was silent. But I don't think he was telling us to f*** off. I think he was telling us that he was sick, and that he didn't want to think about synthesizers. That's what I would think, soldering is what got him sick. So I think that he didn't want to deal with any of this business at that point. And also, I think he would tell us to just go ahead and do our own thing. That's what he would tell himself when he was a younger person. So even though I didn't actually have a verbal blessing, I felt a non-verbal approval to move forward. I feel good about preserving and continuing this design. I've even started contemplating why I feel OK with this, and now I have a script for a video blog or a piece of writing on the concept of a "guild of synthesizer makers."

ET: A guild of synth makers?

PB: Yes, because we don't have that, but I know about the pipe organ makers guild, and I guess there is a violin-makers guild. The thing with the guild is that it is not just about the individual, and it is also not just about the inventions. Someone invents a new organ pipe, but then everybody puts it in their organ. And they keep it going. So a guild is more about shared development and continuity.

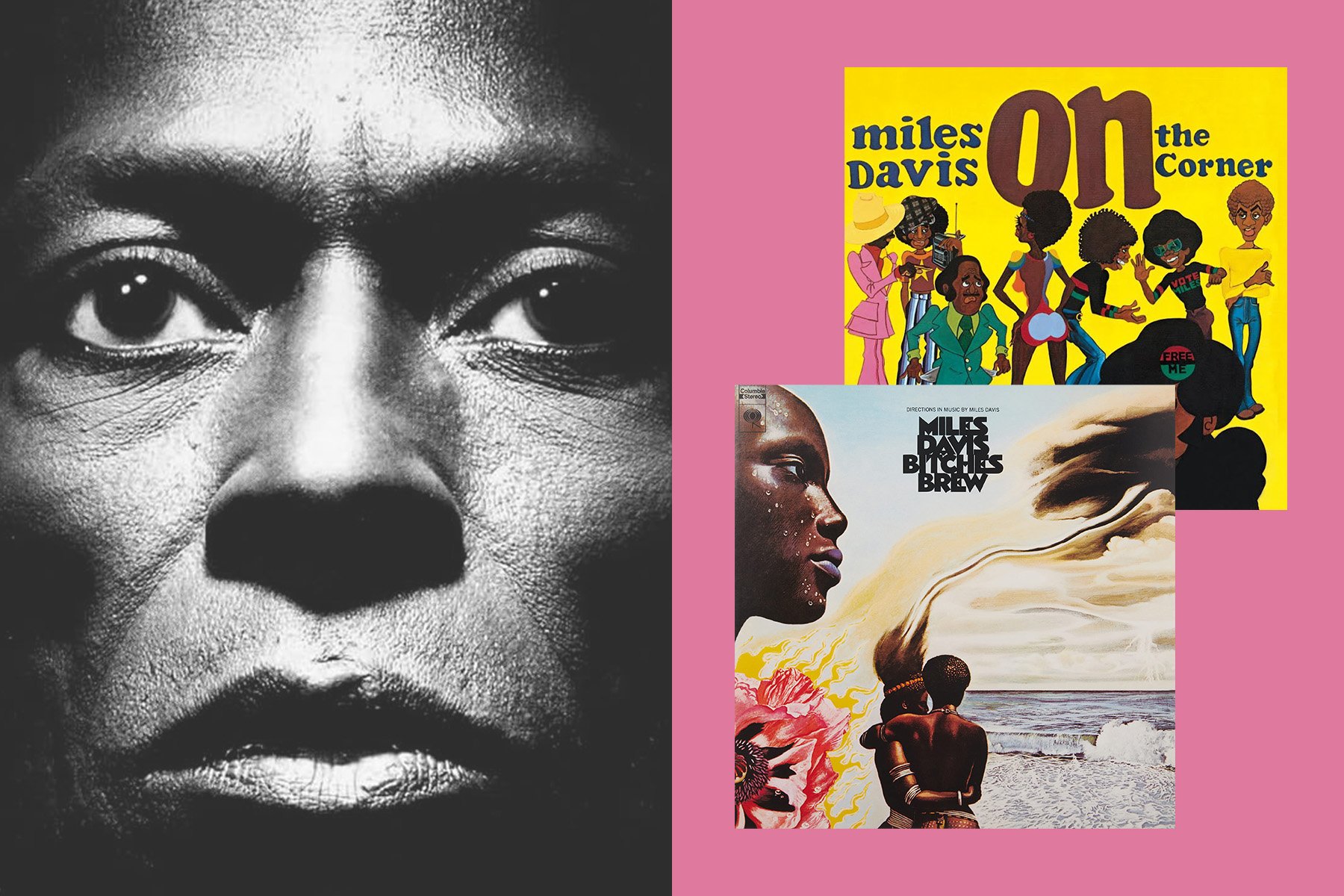

I think that the 20th century was about individuals and inventions in synthesizers, but in my opinion, that was just a short moment. The transistor was invented, and there were a lot of unique things to discover about it, but there is not an infinite amount of things to invent, and I have always felt so comfortable with that. I think that someone like Alvin Lucier would've been uncomfortable with running out of ideas, but I am very comfortable with that. A few composer friends of mine have indicated to me that everyone is trying to invent new things, instead of focusing on simple things, and trying to develop that. For example, David Behrman would only use triangle waves in most of his pieces, and there are so many things to do there.

So I think that there is something comforting about being in a guild. It is sustainable because it is more one person's life, the field doesn't have to die out just because there are no more inventions. It could be like a thousand years of a synthesizer. Just keep it going, share, try to help each other, and maybe occasionally even meet up. The guild idea involves individuals doing reports on their instrument-making activities, where they talk about their influences, respecting people who passed away, documenting, and keeping the research going.

Rob Hordijk had written in the Leonardo Music Journal. I think Leonardo was kind of a guild too. That was good work. But I think the format of a magazine is not very financially sustainable. Leonardo did shut down. So I think a guild isn't even about a magazine. It is more abstract. It is an open concept—as open as possible. A guild is just about the people, so I think it can be sustainable.

All that came from thinking about how to be comfortable with Rob's silence. And I hope I can share my ideas too in a way that they can live on after I'm gone.

ET: I see. This makes me think about the multitudes of ways knowledge can be shared. The magazine is just one way, but there are other ways to do this.

PB: Yes, exactly. An instrument is a way to pass knowledge.

[Above: an assortment of Peter Blasser instruments at the Patch Point storefront in Berlin.]

ET: Now that we are talking about Rob and his legacy, I am curious about some of your personal experiences with him, and also with Don Buchla. I've heard here and there that both played a role on your path as an instrument-builder, and I am interested to know more. Can you talk about it?

PB: Well, my thing with Don was that I was friends with his son (Ezra Buchla). I was lucky to attend Oberlin College. This was also when my dad passed away, who was a great influence in my life. Being an older parent, he encouraged me to be experimental and creative. I was his youngest son, and he fully supported my interests in art and music. I was allowed to make instruments in the basement. So somehow I ended up at Oberlin College, where Don Buchla's son (Ezra) and Serge's nephew (Stefan Tcherepnin) were studying at the same time, and I was in bands with both of them. But I really didn't know anything about the Buchla or the Serge synthesizers that whole time. I think that's why I got along with Ezra—because I was the weird kid who didn't know who his dad was, and I believe that was important to him.

So Ezra played his Buchla, and I remember us trying to mod it. We even broke it once during a rather ambitious modification attempt. Eventually, Ezra did introduce me to his dad. In fact, I was going to take a semester off, and I went to Berkley to apprentice with him. However, soon after I started I freaked out about living there, and I disappeared in the middle of the night...which probably was not such an uncommon thing to happen to a synth maker in Berkeley. So I don't think I have learned much from the dad. However, I do remember one thing that he said that set the tone for how to pass knowledge on. I asked him what value of potentiometers did he use in his instruments? To which Don replied in a very guru-like manner that the value doesn't matter because a potentiometer is just a voltage divider. What he meant was that while you can use pots in other ways, like for variable resistance, when you are making synths everything is a CV, including a potentiometer. This casual sentence taught me a lot. It taught me what not to do, and opened up a lot of ideas from that. I find it to be a great way to pass on knowledge.

But I have also learned something from his son. Don was sick for a long time, and he was going through several operations. He was in a near-death situation multiple times. And I remember that every time we were hanging out with Ezra, he was talking about "hacking" his dad's newest synthesizer and installing his own software on it had he passed away. Then when Don did pass away, I did a lecture at the memorial where I talked about this idea of "hacking the dad." I guess this relates to the guild too because you are releasing your work for other people to go into. When you are alive as a maker, people interact with your instrument from the surface, while you get to design and interact with the insides. This a respectful relationship. The instrument is viewed as a complete entity. But when the instrument is released after the maker's passing, people get to go inside to modify and remix it. And so Ezra was thinking about what he was going to do with his father's synthesizers once he passes away.

The father-son relationship is very specific. For example, Stefan also played Serge, but he wasn't interested in getting inside the instrument and modifying it. The nephew-uncle relationship is in many ways more respectful than one between a dad and a son. For many people, an uncle or an aunt is going to be way cooler than their own parents.

ET: Yeah, I see. There is a distance there. So, do you expect people to "hack" your instruments in the future?

PB: I wouldn't call it an expectation, but more of a resignation to that. Like with the internet, I don't want to own my statements on the internet. Some people are worried about being spied on, but I have resigned to the fact that everyone is looking at you, and I don't want to spend energy to make it all secret. I just say weird things and edit them so they are ambiguous. Just like Don's statement that I've mentioned earlier—"everything is a voltage divider." It is open enough, so there's nothing to steal but everything to learn from it.

ET: I resonate with this. What you say also reminds me of something I heard John Zorn say in an interview—that he doesn't associate himself with the music that he has already released. Once it is out it becomes its own thing, and he moves on to other projects and ideas.

PB: Yeah.

ET: And what about your experience with Rob? You mentioned earlier that you had done workshops with him.

PB: Sure. Do you know Joker [Nies]?

ET: Joker? I recognize the nickname from the Mod Wiggler forum.

PB: Yeah, he's a reviewer. He's a people person and a synth person. He is German. He was in Cologne, and now he is out in the country somewhere. I need to catch up with him and visit his country house. So he was linking people up, and he was good friends with Rob. He introduced me to Rob in Cologne. It was a very sweet introduction. Joker and Rob, these two older men, thought it was important to show me Rob's rungler. That meant a lot to me, this older person really wanting to share with a younger person. But I believe Rob treated every young synth maker that way, not just me.

At that time, I was into doing workshops. I invited Rob to Baltimore. I had a whole house there and access to a giant building. It is a burned-out town, so we could get spaces easily. We would have shows, workshops, and all kinds of things. Bringing people to Baltimore was a project, so I wanted Rob to come. Eventually, we did plan a workshop but it didn't work out as planned. Rob had counted out all the parts for the Benjolin and packed them to be mailed so he wouldn't have to carry them on the plane. But the materials didn't arrive on the day of the workshop, so we just had a lecture. It was cool, but then a week later I had to make all the Benjolins by myself, without him being there. It felt impossible, but we got it done.

I met him a few other times, but I didn't actually apprentice to Rob. He didn't really have apprentices. I shared conferences and workshop tables with him. I think it was the respect he showed me that I appreciated a lot.

ET: Have you ever shown him the instruments that you were making?

PB: Well, I had done a show, and then he came to that show. I was working on some weird stuff at the time. I did an installation at HKW (Haus der Kulturen der Welt) in 2009. It was paper circuits, and a Deerhorn antennae, all patched together. It worked, but it was just crazy. I made this hanging tapestry. As a synth, it was just like "wtf is this." I was proud of my big scrambled paper trash thing, it was like post-modern art. But then Rob brought his tiny "tight thing." And I think this was a great learning experience. It is always a good lesson to see the "tight thing"...

So this all relates to my recent fascination with that one chip—the LM3900. It is not a fancy synth-on-a-chip kind of thing, but a cheap quad op-amp. It all started when I was in some remote part of Germany, for some reason trying to figure out how Serge's DUSG works. It is something I should know, but with this one, you always have to revisit it. In one of the oldest schematics of DUSG, the LM3900 is used in the peripheral place for processing flip-flop logic. This reminded me that I've always wanted to use this chip in my work, because the datasheet for this chip was used like a bible by the '70s sound art people like David Behrman. It has a lot of good stuff and a lot of weird ideas in it. Actually, everything that is in a Serge is kind of in that datasheet in a primordial form.

So I started wondering whether I would be able to create a full-fledged synthesizer using just this one chip. Imagine if a Serge was made only with the LM3900. The thing about it is that it is truly different from a normal op-amp. A normal op-amp has an extra amount of transistors on the input, and it uses voltage. LM3900 on the other hand, doesn't have this layer and allows current to pass through. It is like touching dark matter, you can get to the core of the device. So I've figured out how to use a differential pair to do everything, VCAs, VCFs, oscillators—all that stuff. I can now write a book about this.

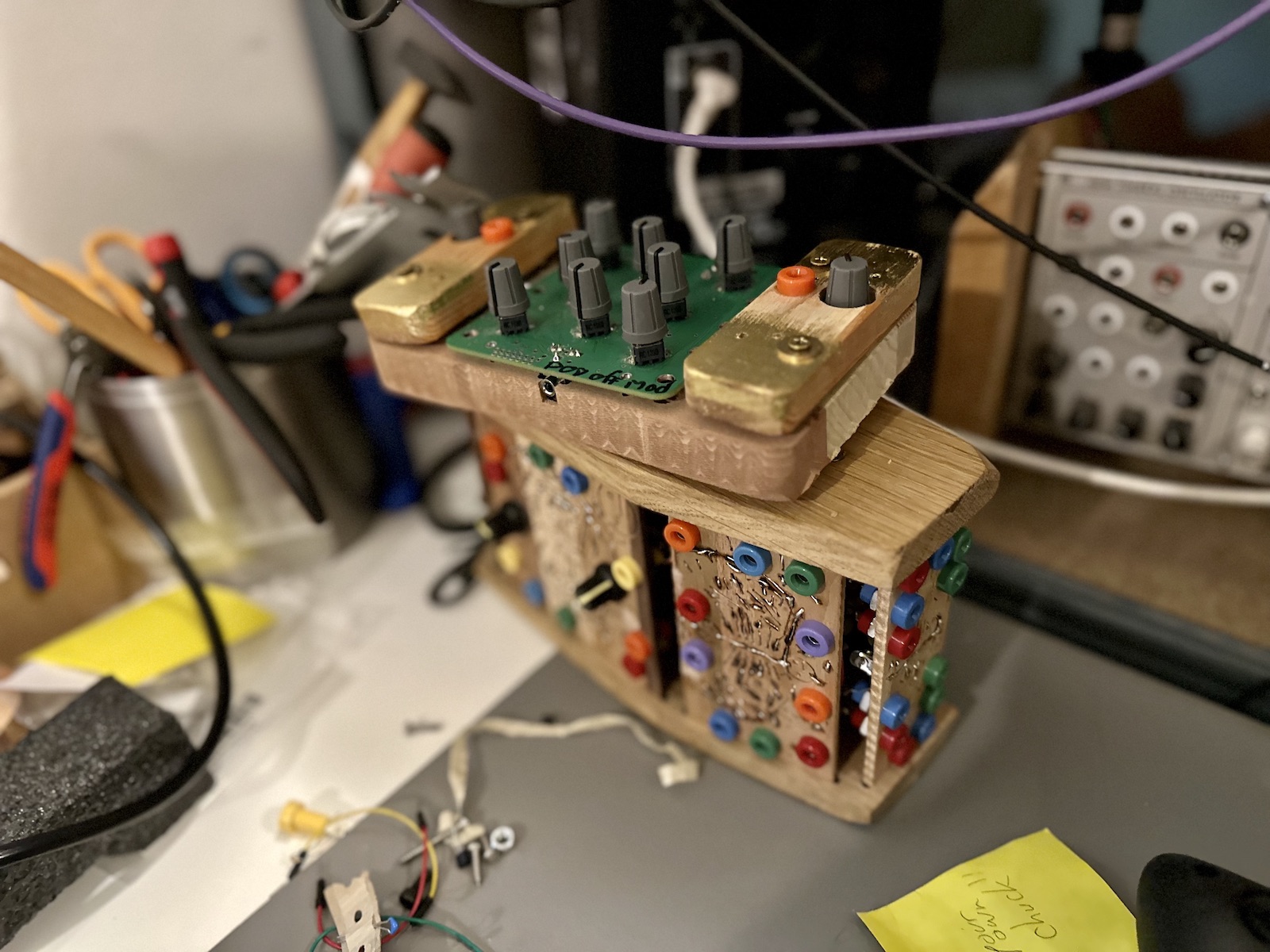

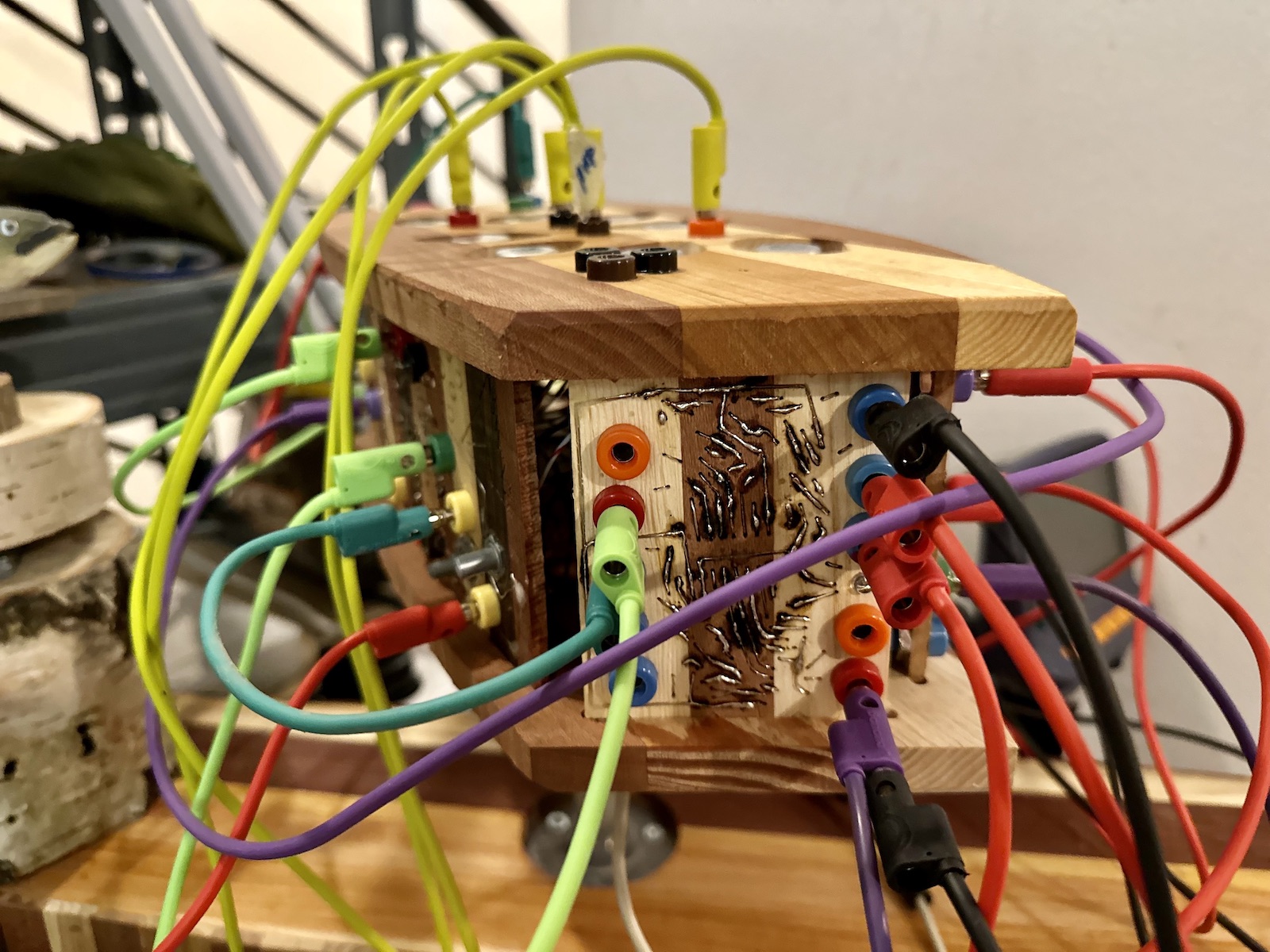

Then I started to design wooden circuits...

[Above: Detail of one of Peter Blasser's wooden circuit designs.]

ET: Is this something of an iteration of your paper circuits?

PB: Yes, but it is much better, and they look much nicer. Paper circuits are difficult to keep for a long time unless you use hot glue or a layer of epoxy. But I never do this. A wooden circuit is done with a CNC machine, and it is really durable. However, one thing that is challenging with this design is that I can't just through a chip like LM3900 onto a wooden surface. This board is 4mm, and you can't get a chip to go through it. So it requires an additional "cradle of leads" installed to fit the chip in. This is a thing that happens often when one tries to design a new format or test a new idea. It can take years of experimentation, and you have to give up a lot in the process.

The LM3900, in particular, has its inputs in a somewhat idiosyncratic formation. They are kind of scrambled, and it feels that there is a secret message there. After spending some time with it, I realized that there is a sort of relationship between the chip leads and the grain of the wood. So the material of the wood and the simplicity of the chip converge to make these new synthesizer modules possible. I am still working on it, but the instrument will be able to do a lot of different things.

The 3900 makes you go very deep. All these nice VCO-on-a-chip and VCA-on-a-chip are great, but they do all the work for you, and they don't make you think. The 3900 really makes you think, and when you go to that core level, everything is the same thing in just different configurations. VCFs, VCOs, and even the Sample-and-Holds are all the same thing, and that is what I'm looking for.

One other thing that I'm making within the scope of this research is a rotating display for the Patch Point storefront using the leftover CNC motor. It is cheesy and dorky stuff, but it makes you go deep. I am using a stepper motor, and here I am allowing myself not to use 3900, although I could use it for the logic. But the cool thing about a stepper motor driver is that it is a primitive rungler, it has shift registers.

The current version of the Benjolin is great to keep the business going, and now I can dedicate my time to all of these other projects. The display is one thing, but I am also working on the esoteric Benjoln where the rungler is made out of the 3900 chips. I have figured out how to do a shift register with the chip, which is complicated but kind of beautiful...that is a part of a guild thing too. These projects are not just for profit, but to go deep.

ET: Are your CNC compositions also related to this process?

PB: Yes, these things are related. Thank you for reminding me. That CNC composition project actually was the thing that started my contemplating on the Serge DUSG. Initially, we wanted to move the Serge system to the CNC woodshop to do this, but it was difficult logistically. We may still do it in the future, but this is not a financially-driven project, and I am taking my time with it.

With the CNC compositions, of course, the easiest way to make music is to just run a program that is already there, like cutting a case. But you can also go the other way around, using an analog computer to generate low-frequency sine and cosine signals to make the CNC move in generative patterns.

It is a bit crazy. The CNC machine, it's a practical tool used to make cases, but it's also part of this journey of "delving deep into the core of things."

ET: We've covered a lot of your practice in electronic musical instrument building, but you originally started by building acoustic instruments, right? How do these two worlds connect?

PB: Yes, I was in a Latin club in high school, and there I began building ancient Greek and Roman instruments. I was particularly compelled by making ancient instruments because there were no recordings of them. We don't actually know what music in those cultures sounded like.

If I look back and think about why I wanted to make these ancient instruments, it seems that it was all about creativity. You are copying an ancient instrument, but you are simultaneously inventing something new. You don't know what it sounds like, so you try to imagine what a particular instrument sounded like. So essentially, you are using your imagination to make an ancient instrument come alive again.

[Above: a Shtar nearing completion on Peter Blasser's work bench.]

ET: Was making a Shtar in some ways also driven by a similar impulse?

PB: Yes, it is practicing the same technique. It is very related. So, when I was working on the kithara, I did a search on AltaVista, that is before Google was a thing, and I got to Harry Partch. That is how I learned about just intonation, and microtuning, which in itself opened a whole infinite realm of creative possibilities. In his writing, Partch also referenced a music archaeologist Kathleen Schlesinger, which also has to do with unrecorded music. She did an anthropological study on ancient Greek instruments "The Greek Aulos" (full title is The Greek Aulos: A Study of Its Mechanism and of Its Relation to the Modal System of Ancient Greek Music, Followed by a Survey of the Greek Harmoniai in Survival Or Rebirth in Folk-music).

Schlesinger studied a variety of bone flutes with equally spaced holes, which from the perspective of the science of tone led her to a false assumption that the pitches were also equally spaced. Not as in an equal temperament, but as an undertone series in just intonation. Harry Partch didn't debunk her theory and instead used the information as a source of inspiration for making his instruments. And I don't want to debunk it either, it is just a part of the story.

If you listen to the undertone series, it is pretty weird. But I think ancient Greek music was actually rather modal and pretty sounding. I believe the way we commonly imagine it is rather correct. The undertone system proposed by Kathleen Schlesinger, on the other hand, was offering something very different. She had the piano retuned to this strange tuning, and she went off to outer space with it, like Sun Ra. But this is totally cool. And even cooler that it is debunked, and we now know that it is not ancient Greek music. It is imaginary music. That space of unrecorded music and unknown musics from history is a place where people can make up new weird things, including alien music through misinterpreting ancient practices.

So I was trying to make ancient instruments, but I also realized that Harry Partch was not actually doing this. He was focused on musically depicting solemn rites and ceremonies. But to me, even as a high-schooler, it was pretty obvious that what he was doing was not authentic ancient Greek music. It was also mixed with Japanese music. There is actually a theory that ancient Greek and ancient Japanese music follow this pattern of convergent evolution, meaning that they developed independently but have some similar features. Harry Partch would always bring these two together into his own synthesis. Which is another aspect of misinterpretation—mixing things together.

So that is the inspirational principle behind the Shtar—not necessarily doing it right, but going off and doing your own thing while maintaining respect and appreciation for the original music.

ET: Is there any particular reason you settled on the 17-tone EDO scale for Shtar?

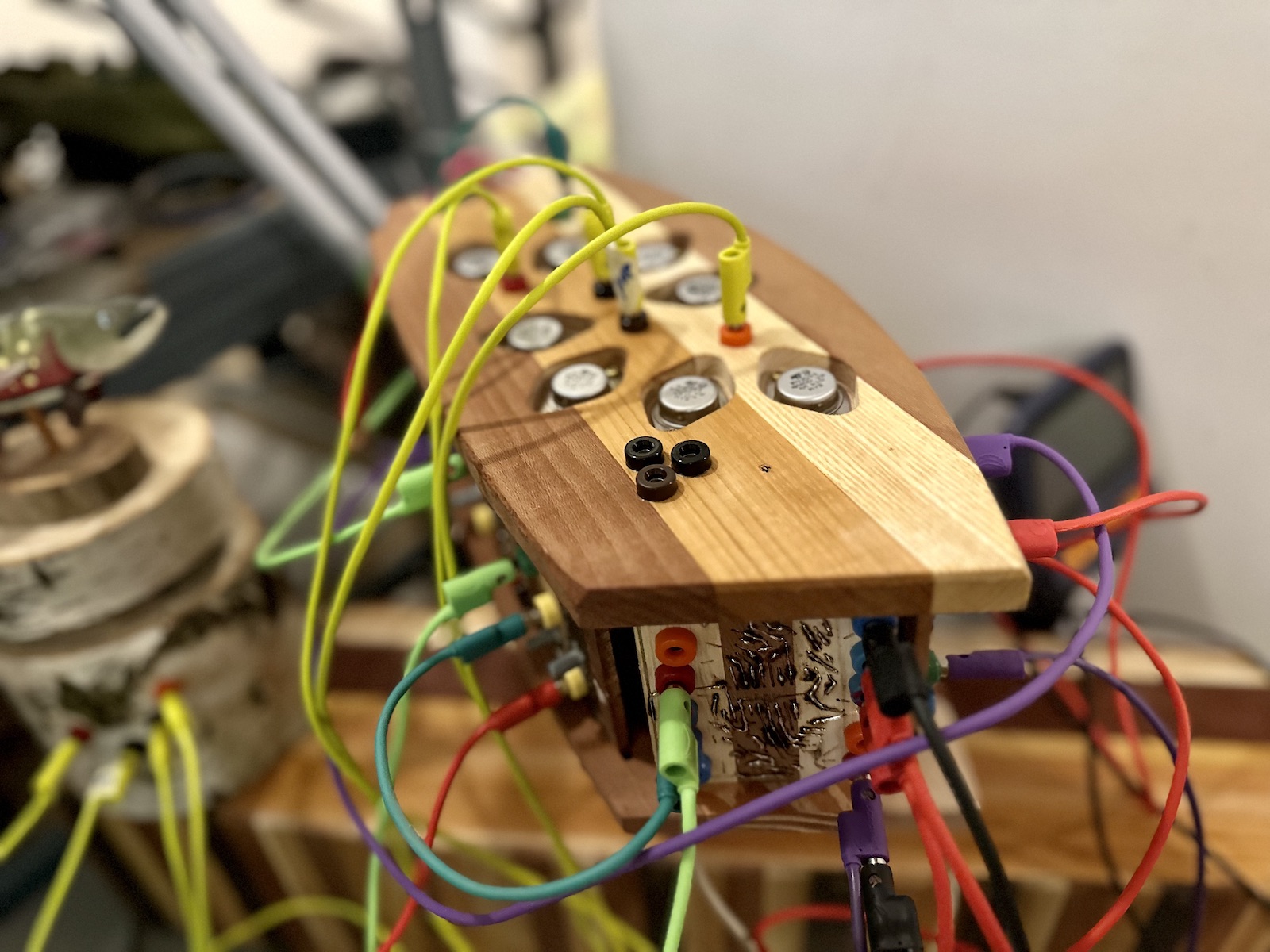

Detail of circuit board used in the Shtar's neck.

Detail of circuit board used in the Shtar's neck.

PB: I wanted to make tar for a long time because I like woodworking. I like how the instrument is shaped, and the particular materials used in making the instrument—a combination of mulberry body and walnut for the neck. Then one of my friends, a kind of friend who does better research than I do, read on some forum about this new experimental 17-tone tuning. So some work on it has been done before I made the Shtar.

For me, it was clear from the beginning that I wouldn't be able to respect traditional music had I just tried to copy a tar. So it was important to approach the instrument as its own thing while making it obvious that what I was working on was part of a global tradition. It is a misinterpretation of the tar. It does stand true that the 17-tone tuning does offer basic access to the neutral intervals, but the equal temperament aspect of it is like a nod to the New York school of microtonal composers who don't just make music that is modal, but also somehow try to create pieces that modulate, which I find incredibly hard to do. So it is about making a different kind of music and not just aping music from an established tradition. To me, this is also a form of respect.

Incidentally, Shtar is a 4-string instrument with the top bass strings commonly tuned a fifth apart, so traditional music styles that are based on neutral intervals like Persian and Arabic music do tend to sound better on it than some newfangled New York microtonal music.

I am also in the process of developing a just intonation version of the Shtar. shLISP, the programming language I developed, is designed to accommodate for just intonation. I wanted to keep the integration of the new instrument simple, so the ratios will be printed on the neck, and you can just enter them in the software and get exactly that note from an oscillator. It is really exciting for me, and I'm trying to get this one out soon. It will be called Tarsh.

ET: Oh, very exciting! When you are designing an instrument do you actually set an intent of how a user should approach it?

PB: I don't. Like with that wooden instrument I mentioned earlier, the design for me is about working from the core. There is a goal for the CNC synth to sound like dubstep, but this is just a cheesy high-schooler in me setting an arbitrary yet possible goal. But in the end, it is all left to the users to come up with their own ways of playing the instrument.

ET: Alright, Peter! Thank you so much for the conversation, and we are looking forward to all of your upcoming projects.

PB: Thank you. Bye!