As musicians, we make stuff with other stuff - namely music, made with instruments and other equipment. This may seem at first a pretty simple concept, but there is a deep complexity in the whole arrangement. The stuff we use is (usually) made by other people, who we entrust to provide us with useful and inspiring artistic tools. They define not only how an instrument makes sound, and what it sounds like, but also what sort of physical interactions can bring about those sounds, how it feels, and how it looks. Those people, the stuff-makers, are further dependent on an international system of stuff-making, which whether we like it or not, places restraints on what can be made. Generally speaking, none of these complications see their way into our music making, largely due to the creative efforts of people like Axel Hartmann.

Even if you aren't familiar with Axel Hartmann, in the synth world it is nearly impossible to miss his unmistakable mark on synthesizer design. Since his entrance into the industry as a young designer in the late 1980s, Axel's work designing the physical form and interface for Waldorf's instruments has earned him substantial renown, leading to successful partnerships across multiple manufacturers. A comprehensive list of instruments that have benefited from Axel's focused approach to imaginative and inspiring designs may as well be a list of the most notable synthesizers in the modern era - the Waldorf Wave, the Access Virus Polar, Moog's Little Phatty – or more recently, the Moog One, the UDO Super 6, and even the kid friendly BlipBlox from Playtime Engineering. Chances are, if you like synths, you like one of Axel's designs.

Axel's design work results in instruments which captivate the eyes but also pays serious attention to the fingers and hands, delivering innovative tools that inspire musical action. Despite a level-headed approach to the constraints of industry and consumer demand, Axel's designs communicate a firm commitment to innovative instrument interfaces that stems from his own musicianship and passion for sound. Especially with NAMM now in full swing, with plenty of new devices hitting the market, we were overjoyed to get the opportunity to pick Axel's brain about his illustrious career in creating instrument interfaces. In the interview, we get into Axel's early days as a designer, explore some highlights from his unique career, and consider how design shapes the musical experiences we create with electronic instruments. Read the full interview below!

An Interview with Axel Hartmann

Perfect Circuit: Your position in the industry is fairly unique, having been able to work with a wide variety of manufacturers in fusing your distinct style with their brand identity and project. At what part in the process are you typically contracted?

Axel Hartmann: We usually get involved when the client has at least provided a functional specification for the project. Over the years, we’ve built a reputation with the agency as specialists in electronic music equipment, especially in the world of synthesizers. As a result, some clients book us as sparring partners to help with the development of an instrument’s user ergonomics. So, sometimes, we’re actually brought into the process a bit earlier. As industrial designers, our primary role is, of course, shaping the form. But our services go beyond mere aesthetics, extending to construction and product graphics.

PC: I understand you were interested in music and synths in addition to the visual arts in your younger days, which helped lead you to your particular niche. What sort of musical experiences drew you to synths in particular, and how did your interest in visual art translate into industrial design?

AH: My love for music began many years before my passion for art. I sang a lot as a child and would imitate the voices of radio stars. Eventually, I heard a song that featured an organ solo ("Mendocino" – the German version of Doug Sahm’s original). The sound of that organ gripped me so much that I relentlessly pestered my parents to let me learn how to play one. Then, my grandfather brought home a very old, second-hand piano from a customer, and convinced me that in order to play a Hammond organ, I first had to learn the piano. So, at the age of nine, I started taking piano lessons. By 14, I finally managed to buy an organ with my confirmation money and some contributions from my parents and grandparents, at the nearby Matthias Music Store in Idar-Oberstein. It wasn’t a Hammond – at that point, I didn’t even realize that Hammond was a specific brand. All electronic organs back then were simply called Hammond organs... This one was an Italian Farfisa organ, complete with a built-in rhythm machine and a stubby pedal. But I never really warmed to it. The sound didn’t fit, and the way I was taught to play led to a rather uncool, carnival-like interpretation of the songs I loved. I much preferred playing the piano.

[Above: A selection of some of Axel's notable designs.]

Eventually, I traded the Farfisa for a Yamaha YC25D – still not a Hammond, but with a little Leslie cabinet we later bought (not an original Leslie, but an Italian version from “Davoli”). With a guitar distortion pedal in between, the sound was much closer to what I liked – almost perfect for a Deep Purple vibe. We formed a band. But something was still missing – the sound I was hearing in the new songs on the radio. Soon, I realized there was a new type of keyboard instrument on the market: the synthesizer! The Matthias Music Store was one of the first dealers in the region to offer the full Yamaha lineup. The cheapest synthesizer I could find in the catalog was the Yamaha CS10. I had no idea what I was ordering. When the unit finally arrived and sat on top of my organ, I dug through the manual and slowly started to understand how the different modules interacted. I soon managed to coax useful sounds out of it that worked great in the band context. Alongside this musical journey, I also started developing an interest in drawing – but more specifically, how my instruments felt and looked. How my entire music setup presented itself on stage. This was always important to me – not just visually, but ergonomically (though I didn’t even know the term back then... ;) ). I think this was the first fusion of my two passions – perhaps the starting point.

PC: Does your design work ever provide the ability to inform aspects outside of physical build and aesthetic? Have there been situations where a physical or aesthetic design choice helped direct the sound or functionality of a device?

AH: This is a very interesting question, and I hope I understood it correctly ;) Actually, when I think about it, this is exactly one of the aspects that makes innovative design – or even a novel, exciting user interface – so fascinating. Materials and colors play a crucial role here – the tactile quality and the behavior of the instrument when you interact with it. Let me give you an example: the Hartmann Neuron. Its translucent stick controllers are shaped like something from nature. They feel organic, delicate – tactile. And they allow deep manipulation of the sound’s core through subtle movements. Perhaps it’s the combination of these two worlds that enables such an intriguing approach to sound manipulation via an unfamiliar movement process.

PC: Your diploma project in university was a design for a unique workstation/arranger keyboard with a swivelling screen display for use by two operators simultaneously, called the Gambit, which you finished the model for around the end of the 1980s. What inspired you to focus on a workstation in that project, and how did you arrive at its unique two-person design?

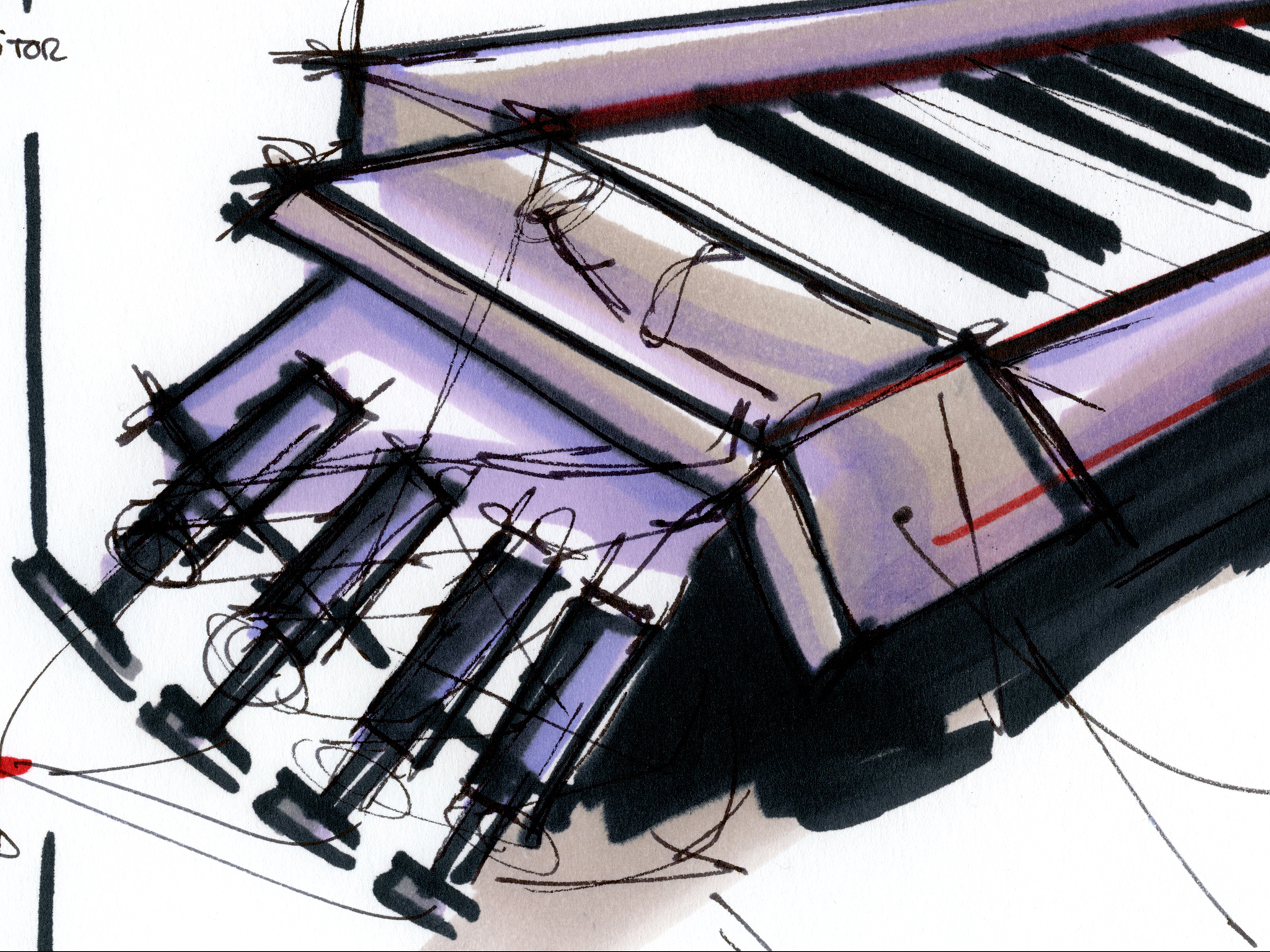

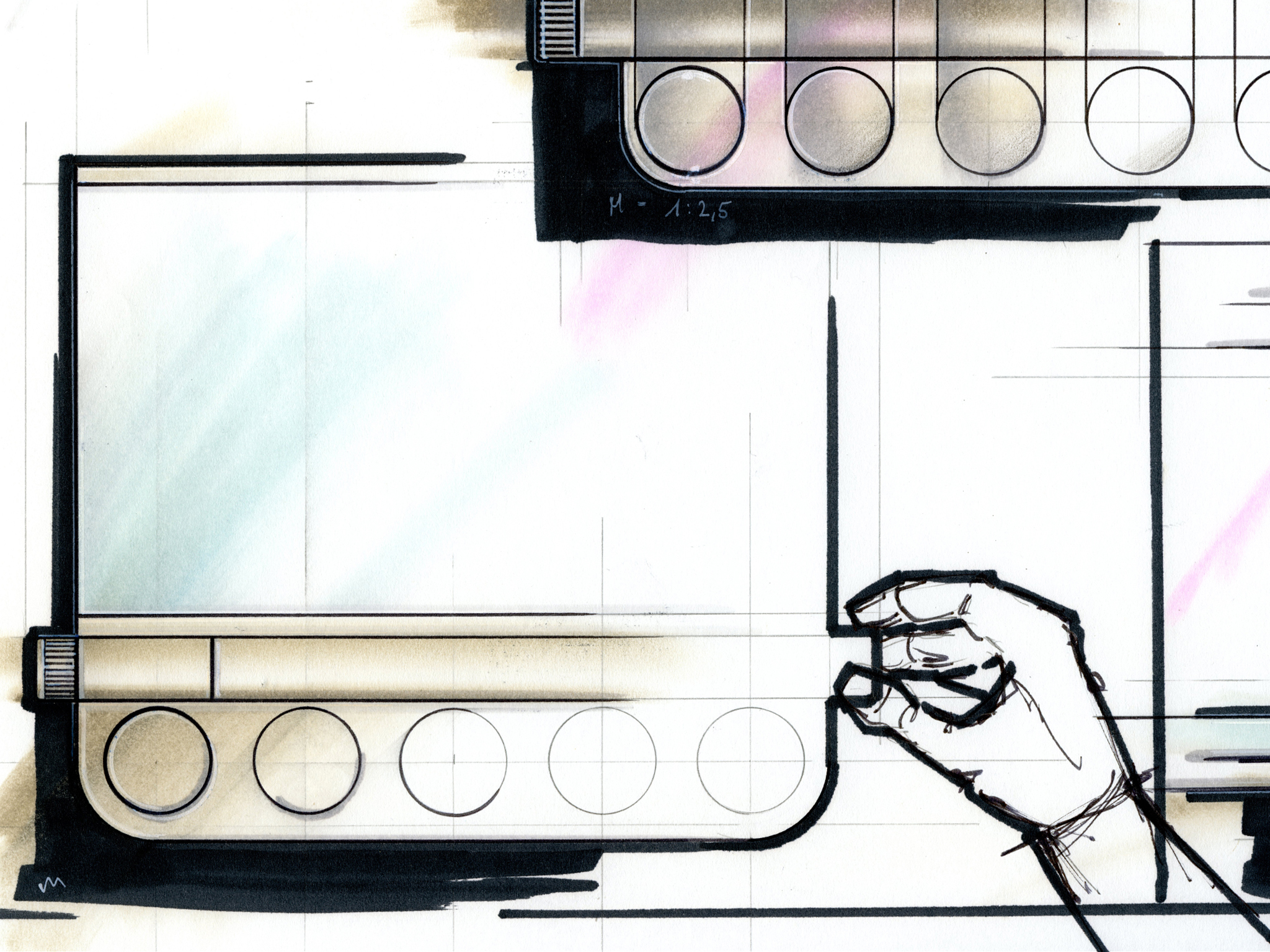

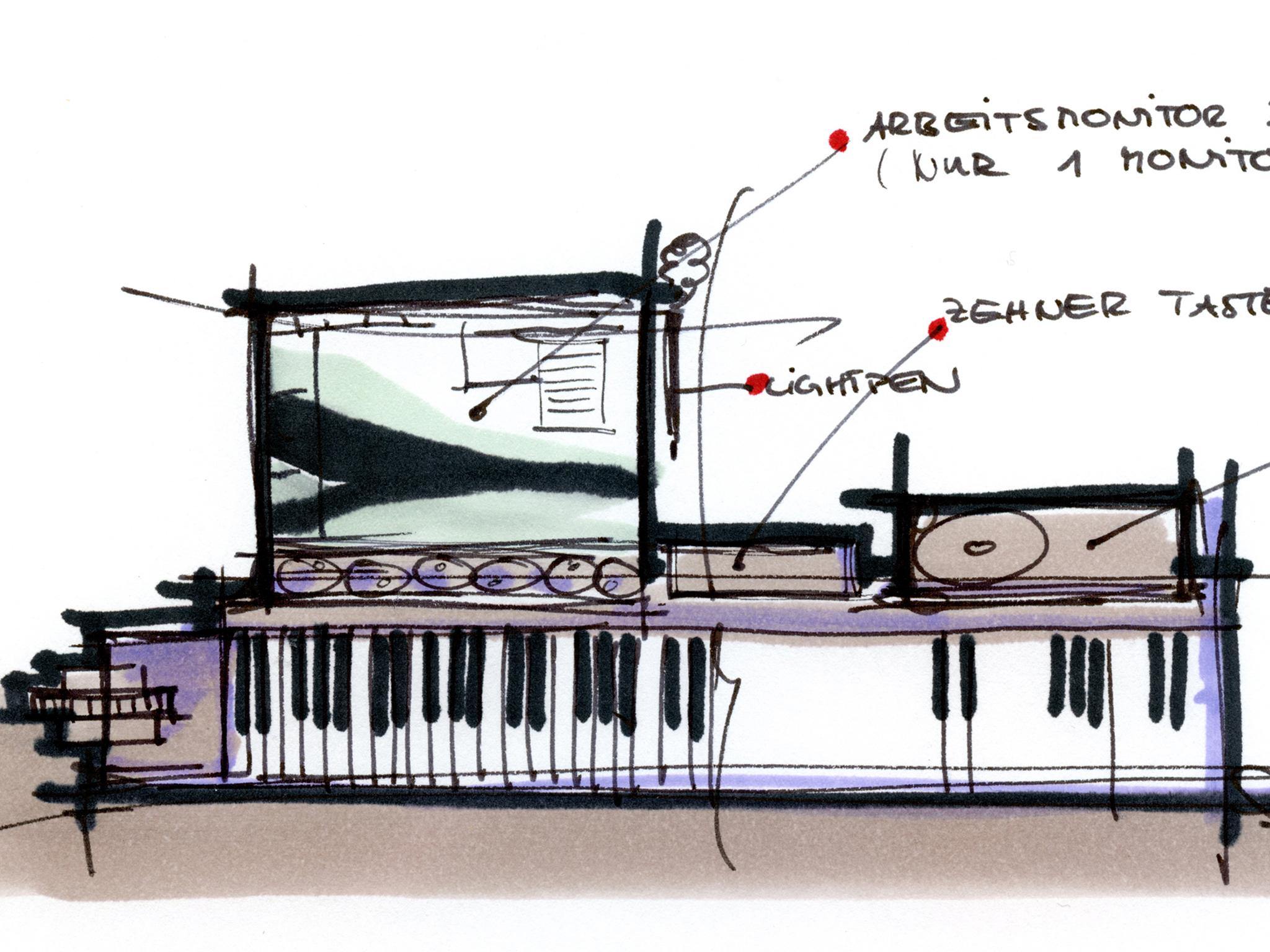

[Above: Axel Hartmann's university thesis project, Gambit, with design sketches.]

AH: The late '80s were the heyday of digital workstations. Instruments like the Synclavier and Fairlight CMI took on the technical tasks of recording and processing, while still offering the instrumentalist a traditional black-and-white keyboard for input. From my own experience, and also from observing various music producers during my thesis work, I realized that these were actually two separate tasks that might be better handled by two people with different areas of expertise. That’s why I gave Gambit a rotatable screen. This allowed one person to continue working on the system as usual, but also made it possible for two people to sit opposite each other, collaborating – much like a studio setup, with the producer on one side of the glass and the artist with their instrument on the other.

PC: I imagine back then you had some idea of where synthesizer design might go, or at least where you wanted to go with it in your own work. How does the modern landscape of synth design compare to your outlook in those early days?

AH: These early days came about a good 10 years after the Prophet-5 was released. In the meantime, 16-bit samplers appeared, and studios were filled with these machines, allowing for total recall and deeper manipulation possibilities when used with computer-based sequencers. I already knew back then that the user interface would play a crucial role in future instruments. Essentially, it’s still the same today – just with over 30 years of exponential development in between. Today, you can say with confidence that even affordable audio products are capable of delivering outstanding sound results across the board.

The key quality metric for good product design in our field is increasingly the human-machine interface – the user interface. That’s why I consider it just as important now as I did back then. What’s thankfully making a comeback – and what we all love, because we’re human with hands and fingers – are control panels with real knobs and switches. Back in the '80s, during the digital craze, this didn’t seem likely. But now we know better – and we’re seeing the same phenomenon in modern cars. The shift from purely digital displays to real knobs and switches for key functions is already happening.

PC: Across the many successful and innovative projects you've been involved with, are there any that stick out as having been particularly impactful to you, imparting some important lesson that would carry on into your subsequent work?

AH: I’d highlight the collaboration with Moog Music. As a synthesizer nerd, it was a huge honor for me to work with the inventor of the very instrument I love. When I first attended the NAMM show in 1990, shortly after completing my design studies, I had an encounter at the Anaheim Hilton. My boss at the time, Wolfgang Düren, pointed to an older man with gray curls and said, “Look, that’s Bob Moog!” Until that moment, I hadn’t realized that the brand name actually came from a person. We met again at other NAMM shows, during a time when Bob had to call his company Big Briar, and I would often chat with him. Then, in 2002 at the Winter NAMM in Anaheim, our booths were next to each other. I was there with Hartmann/Neuron, and Bob was with “Moog.” Kneeling beside his prototype, he was carving out the mod wheel with a pocketknife because it wasn’t running smoothly, or wasn’t fitting properly.

[Above: Multiple editions of the Moog Voyager, Axel's first collaboration with Moog.]

His down-to-earth, friendly demeanor hid the genius behind the man. I found that scene incredibly touching and asked if I could help. We started talking, and I offered to rework the Voyager’s design with our technical capabilities. I felt the panel design wasn’t quite right. Bob let me rework the graphic design in the weeks that followed. In return, I managed to negotiate a Voyager for myself. That was the first connection. This led to many years of collaboration, during which I had the pleasure of designing several iconic Moog instruments. But soon, I learned of Bob’s illness. During the development of the Little Phatty, he had to step back, and Cyril Lance took over. We continued the project with the Moog team, but unfortunately, the instrument wasn’t introduced until 2006, after Bob’s untimely passing. I wish I could have gotten to know him better – what an honor that would have been.

Moog is a very special client, with an incredible legacy, a unique brand DNA, and a distinctive look that’s visible in every instrument. The idea behind the Little Phatty’s curved back panel came from one of my hand sketches, where I was trying to achieve the ideal, but steep angle for the front panel without making the instrument appear too bulky. The fact that this detail, combined with the manufacturing technique (using an aluminum extrusion profile), met both mechanical and production requirements was a stroke of genius – one of those moments in life that doesn’t happen too often. This element went on to define the Moog brand for many years and was kept in several product generations.

For any designer working with a well-known brand, the key challenge is to maintain the essence of what’s good and familiar, while transforming it into something innovative and fresh. This is a service on one hand and an art form on the other. This balance contributed to Moog’s brand resurgence. The process taught me to sometimes set aside my own ideas and to respect the brand and the people who fill a beautifully designed case with exceptional technology. I hope that doesn’t sound too dramatic...

Sketches for the Moog Little Phatty hint at what would become its iconic back-panel swoop.

Sketches for the Moog Little Phatty hint at what would become its iconic back-panel swoop.

PC: I understand from other interviews you've given that modular formats aren't something that particularly interest you as someone who, as both a musician and a designer, seems to be attracted to enabling deep player-instrument relationships rather than "telephone box" style programming of self-playing instruments. What inspires this prioritization of realtime, performative control, and how does it inform your work in music and/or instrument design?

AH: It's not that modular synthesizers don't interest me—quite the opposite, actually! I've been following the renaissance of this genre over the past decade with great interest. There's an incredible amount of spirit and innovation happening there. Many module manufacturers are incredibly creative—not just in terms of technology but also in the sometimes wild, unconventional, and occasionally "handmade" graphic designs for the panels and controls. It's a huge field of inspiration—even for me as a designer!

As a musician, however, I love the direct interaction with a keyboard—the connection between my fingers and the black-and-white keys. I’ve never used loop sequencers, arpeggiators, or similar tools in my own music. Modular systems, for me, can often feel too complex. But for enthusiasts, that's the whole appeal: exploring and manipulating sounds while they’re triggered by sequencers.

So, both "worlds" (keyboard and modular) definitely have their place. Personally, though, I find it more fitting when an instrument offers a closed system with limited or predefined capabilities. That’s when product design can really shine, exploring its full depth—both aesthetically and ergonomically. For me, it’s much more exciting to design a full instrument rather than a desktop or module.

PC: Something that fascinates me about electronic instruments is that unlike acoustic instruments, their comparatively brief history and development within modern industry seems to lend itself to the pluralistic nature of electronic instrument design. For example, acoustic string or brass instruments have seen far fewer and less dramatic innovations in their physical form or sound, while synthesizers continually change, with new sound engines controlled by increasingly sophisticated or adventurous interfaces. It's hard for me to imagine synths ever having the same resistance to change and new ideas like acoustic instruments, even far into the future. What do you think is particular about electronic instruments that demands this radical openness to innovations in form and function?

AH: Isn't the form of traditional musical instruments always determined by the fundamentals of acoustics and physics? What we now consider the perfect violin, piano, or guitar is the result of centuries of research, refinement, and optimization—the adjustments have become increasingly minimal because the optimum has already been (almost) found. The uniqueness of these classical instruments lies mostly in their specific sound, which is acoustically generated. This interplay is only partially present in electronic musical instruments. Instead, their appearance is almost entirely detached from their sound, unless the interface—the way the instrument is played—requires a special form. Many innovative synthesizers that have gained wider appeal look, well... almost identical at first glance, especially when viewed from a distance or photographed in black and white. You get a case, sometimes a built-in keyboard, and a user panel. What happens inside is what makes the difference.

[Above: Axel Hartmann's own Hartmann Neuron Synthesizer, released in 2002, featuring neural network inspired sound engine and custom interface elements.]

Occasionally, a new human-machine interface is introduced—like with the Eigenharp, Linnstrument, Soma Terra, etc. But the market seems to be less welcoming of such novel concepts, or they require a steep learning curve, which often discourages users from engaging with truly groundbreaking technology.

PC: While you've designed a ton of successful synths and other products that didn't have keybeds, it strikes me from interviews I've read that you yourself have a strong affinity for a big, proper keyboard instrument. Many are probably familiar with the history of chromatic keyboards ending up as primary synth interfaces via musicians suggesting it to Robert Moog, and for some good reasons that legacy has continued into the modern era despite some obviously important counterexamples. Given the long history of keyboards in synth design (and of course far beyond it), does the presence of a keyboard change the way you approach a project?

AH: The most successful and revolutionary synthesizer technologies of the past 50 years have almost always been introduced as keyboards—please correct me if I’m wrong. Honestly, I think that even in the foreseeable future, innovations in the synthesizer world will likely appear as keyboards (or modules). And that's not a bad thing, because the user interface can evolve and integrate with the new technologies. I think—and hope—future interfaces will still be operated with hands, fingers, and perhaps even foot pedals.

For me personally, designing a keyboard is almost more enjoyable—it has a more complete, powerful, and impressive impact than a desktop or module could ever have.

PC: Outside of fully controllable keyboard instruments, you also have designed many rack mounted and desktop units (like the wonderfully classic Waldorf MicroWave) which require additional peripherals for the full playing experience. Are there particular considerations you take when designing an interface intended to be expanded with controllers and other devices?

[Above: A print advertisement for the Waldorf Microwave ca. 1989]

AH: Designing a rack instrument presents unique challenges. I realized this early on when, as a young designer, I created my first instrument for Waldorf—the MicroWave. It's more like painting a picture. Everything happens in a largely two-dimensional space. Of course, you still deal with ergonomic considerations, but what really mattered to me at the time was finding the perfect balance between the elements. It's like aiming for the golden ratio in a photograph. For the MicroWave design, I stuck closely to these principles. The display was moved from the center to the left, which made it more ergonomic for right-hand operation. The "red nose" became a bright new element that helped distinguish the young brand. We also wanted to create a color accent to break up the otherwise predominantly black 19" rack modules. Since the early 90s, though, the 19" format has lost some relevance in synthesizers. Today, when designing a desktop synthesizer, it's often a secondary requirement that it can fit into a 19" rack (with adapters). More important now is the VESA mount on the underside.

PC: Conversely, how have you approached designing controller peripherals without onboard sound generating capabilities, as in your work on the Novation Impulse, Studiologic Numa, etc?

AH: A pure controller keyboard should feature ergonomically well-balanced controls. These need to be easily accessible and provide an optimal workflow for a variety of applications. I view controller keyboards like a blank canvas—designed to be as universally applicable as possible (unless the client wants to use it with exclusive or specialized software). The market for keyboard controllers is fairly saturated, so it's essential that each brand presents its philosophy clearly to its target audience. There's also a lot of price competition in this segment, which influences design choices, often making them very budget-conscious. This means the design approach is driven by these parameters. Even in the earliest design phases, we focus on specific manufacturing processes and avoid any detours that wouldn't realistically translate into an industrial product. It’s a difficult task, but always a highly interesting one!

PC: Hardware instruments provide opportunities to interact with sound via physical movements, and these sound-action pairings can themselves become notable musical motifs - the filter sweep, for example, is a "knobby" gesture, not that dissimilar from how the space between strings on a guitar enables strumming, the rebound of a tightened drumhead enables buzz rolls, etc. Are these sorts of sound-action mappings - either established or new - something you often consider in designing new synths and other interfaces?

AH: Yes, absolutely! But in most cases, it’s still the traditional left-hand control elements—wheels, benders, or joysticks—that gain broad acceptance in the market. Only a few manufacturers are willing to take the risk of developing something new. Some even backpedal, like Native Instruments, who replaced pitch and modulation ribbons on their controller keyboards with wheels in the second iteration—likely in response to user demand. Arturia took a chance with the Morphé controller on their Polybrute synthesizers, but they’ve also added the classic wheels alongside it.

Throughout my career, I’ve tried several times to offer new, active control elements in early design studies that were purely aimed at enhancing the player’s performance (like with my thesis project "Gambit"). We further developed these for a potential reissue of the Waldorf Wave in the early 2000s and even modeled them in 3D. But then the question always arises: What’s the development effort involved? For smaller, exclusive manufacturers, it represents a significant additional workload, aside from developing the instrument itself. For many, it’s just too risky.

PC: When you encounter a new project for something particularly complex, how do you decide when to achieve functionality through a graphical UI versus knob-per-function control?

AH: In most cases, the decision isn’t ours, but is determined by our clients. If we're involved in the decision-making process, we typically start by graphically representing the operation/control of a complex function, then look for ways to make exploring this new function fun—or to guide the user toward the desired result. Based on that, we propose how to implement it.

PC: Much digital ink has been spilled over the pros and cons of so-called menu diving - yet instruments you've designed that do feature deep screen menus, like for example in the Waldorf Iridium, seem to achieve a healthy balance of deep control and intuitive user experience. How do you approach digital menus such as these to find the right balance between sound design depth and usability?

AH: For the new Waldorf instrument generation—Quantum and Iridium—these are heavily display-driven instruments. A lot of research and development has gone into seamlessly integrating display-supported features into the workflow. The principle was conceived by Rolf Wöhrmann, who also designed and implemented much of the interface. Except for the Core model, all the essential synthesizer components are directly accessible via hardware controls. Where the sheer volume of parameters would overwhelm an intuitive control system (with double or triple assignment of knobs or buttons), the graphical display steps in with clear representations to assist. It’s essential that the touch display works smoothly—like an iPad. Many contemporary synthesizers/workstations fall short of this standard, leading to user frustration. I believe that combining genuine hardware controls with good displays holds great potential for creating novel interface ideas.

PC: You've worked on a number of instruments with a particular focus on fun and accessibility, like the BlipBlox synths from PlayTime Engineering, and more recently the Stylophone Theremin. Did your approach for these kid-friendly and fun instruments differ considerably from designing more supposedly "serious" or "adult" instruments?

AH: The design approach for these is generally the same as for serious adult synthesizers. However, we are aware of the target audiences, so we incorporate specific ergonomic requirements into our work. This process is always based on a briefing we receive from our clients when working on an offer. These special synthesizers are a lot of fun for us because they let us think and draw in a completely different direction. But even then, the client expects a viable solution for their project, and the design development is handled with the same level of professionalism as with more traditional projects.

PC: If you were to work on a design project that wasn't explicitly musical, what kind of products would be most exciting to you?

AH: What do I like best? I like everything with a power plug—ideally, something that makes music. But that wasn’t really the question, was it? Hmm, not so easy... Maybe a turntable? You see, it’s difficult. I’m just where I belong—and where I’ve always wanted to be. :)

[Design sketches and instrument images courtesy of Axel Hartmann]