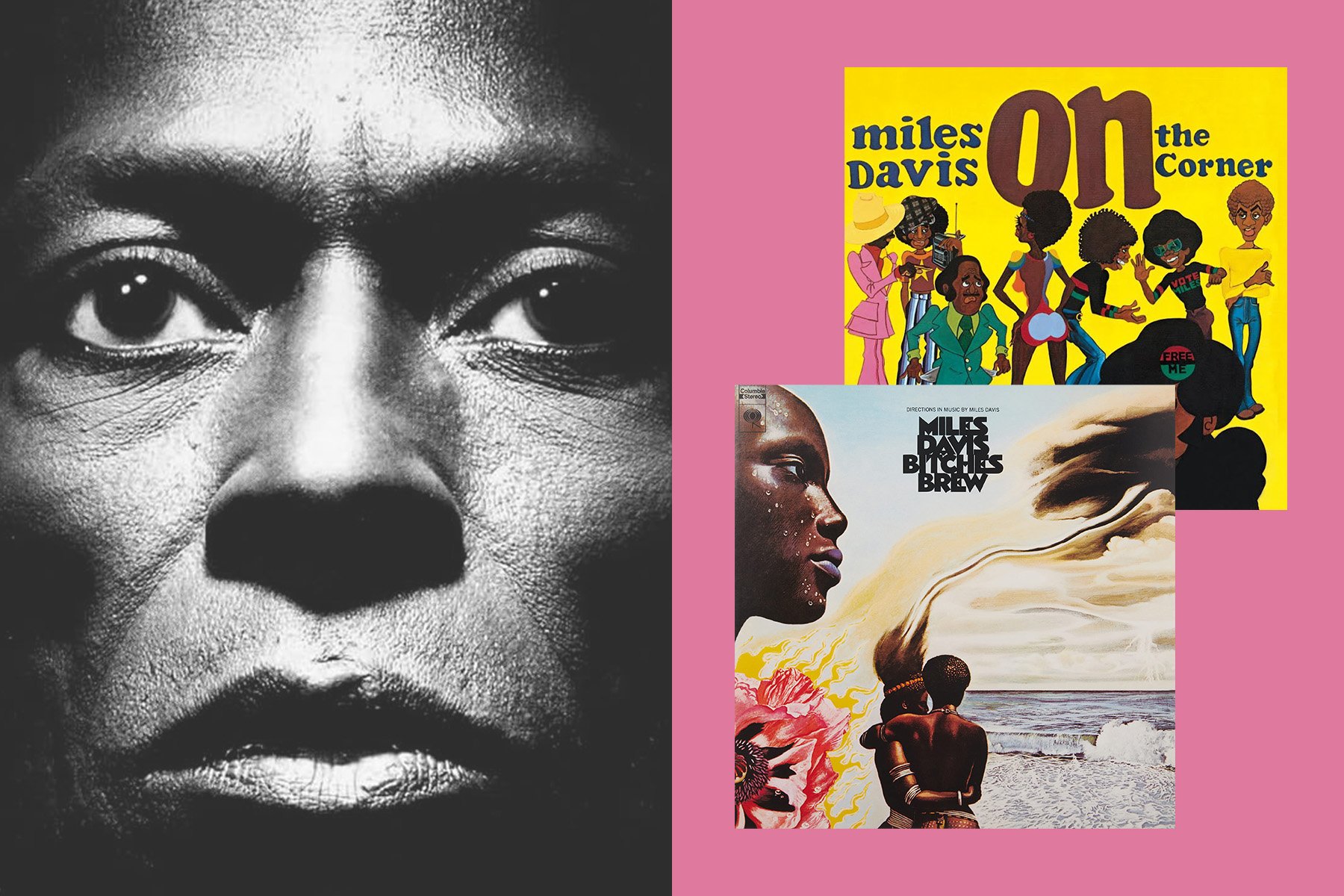

If you think about synthesis in the 1980s, there's a good chance you'll think about FM synthesizers... if not the Yamaha DX7 specifically. Yamaha's domination of the synthesizer market led to an abundance of spinoff instruments and supplementary products aimed at putting some of the DX7's magic into the hands of more people. Classics like the DX100 and TX81z are some of the most well-known devices to follow the DX7, but would you believe that Yamaha also built an FM synthesizer into a computer?

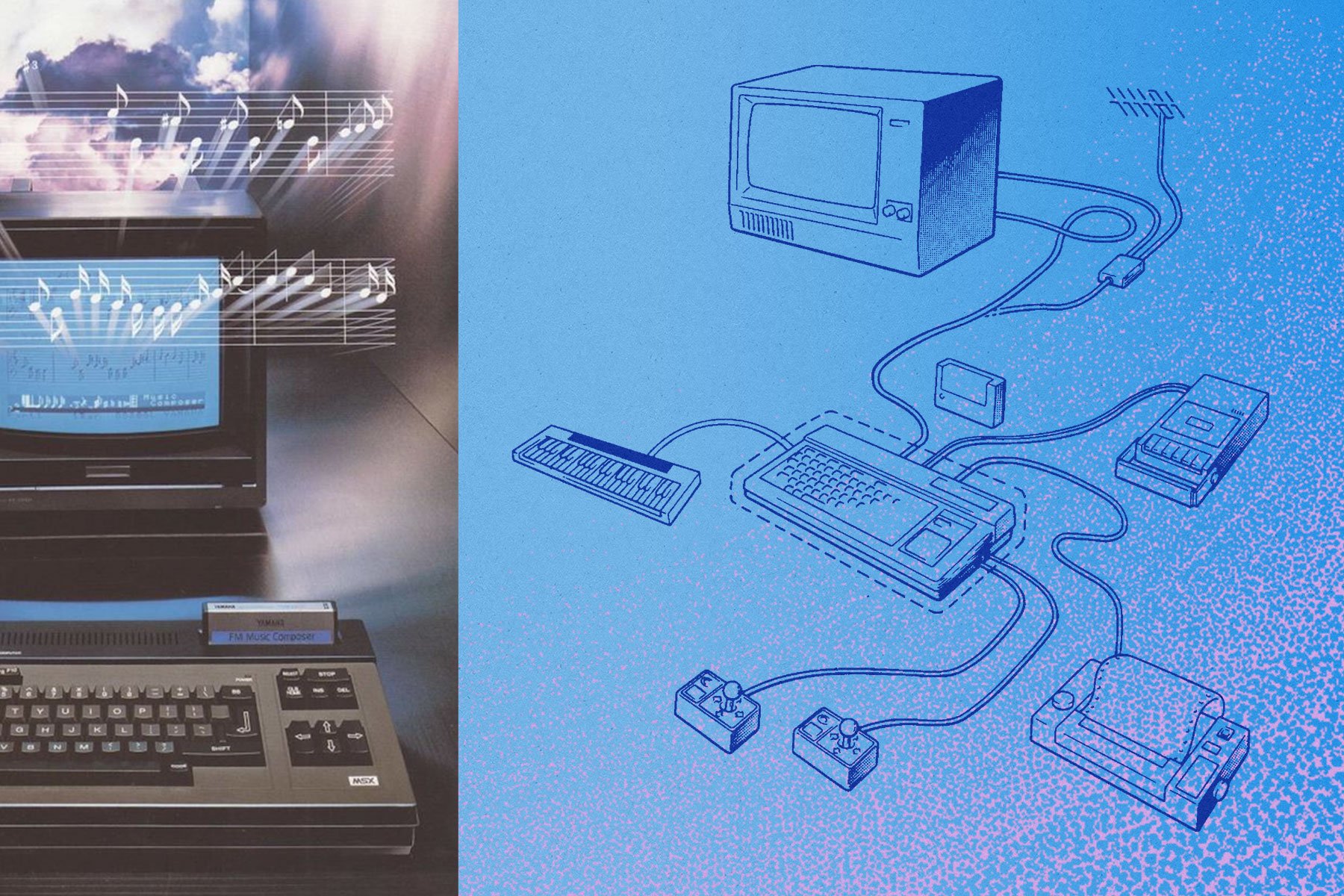

That's exactly what Yamaha did with the CX5M: an MSX computer loaded up with an integrated FM synthesizer and MIDI I/O. Of course, it could easily interface with the DX7 for advanced control and organization of sounds with a graphical interface, but the CX5M had the potential to be a formidable instrument in its own right. Even if our collective concept of what a computer is and the things it can do are much different now than they were 40 years ago, you might be surprised at how much of what the CX5M does, at least in terms of its musical functions, is actually similar to modern machines.

I find the CX5M to be a sort of technological time capsule—with the right equipment it's still completely functional of course, but worlds apart from contemporary computers and software in terms of user interface and power. However, there's something to be said for looking back at something like this and appreciating it for what it offered at the time it was introduced, and being very thankful for the advancements in technology since!

What is a music computer, and where did they come from?

In the year 2024, it's hard to imagine making electronic music without using a computer in some way, shape, or form. If someone asked you to envision making music with a computer, you might first think of the typical electronic music producer running a DAW and plugins on their laptop. But if you stop to think about it, what is a computer, really? We can stretch our definition to include the many smartphones and tablets that are also able to run a variety of music applications. Yet why stop there?—we can cast an even wider net on multifunctional digital devices with decidedly musical purposes.

One approach that's gained some traction in the past few years is to externalize DAW-like workflows into full-fledged computers dressed up as controllers, rather than using traditional computer peripherals like a keyboard and mouse. Ableton's Push 3 and Maschine+ from Native Instruments capture the magic of their respective software platforms, while AKAI's MPC Key 37 and MPC One+ build on the Music Production Center legacy with a contemporary DAW-style spin on sampling and composition. And like traditional computers, these are all expandable to support external MIDI controllers, control modular synthesizers, connect with USB storage devices, and otherwise directly interact with other musical tools.

[Above: AKAI MPC Key 37. Image via inMusic]

Others like Norns by monome or Critter & Guitari's Organelle are more akin to single synthesizers on the surface but are built on Linux platforms to support open-ended user programmability through scripting and programming environments like Lua, SuperCollider, and Pure Data. You could make the argument that music computers of this type can trace a lineage back to fixed-purpose devices like Teenage Engineering's OP-1 and Elektron's Octatrack, which themselves can be seen as specialized offshoots of the samplers, sound modules, and keyboard workstations that came into popularity 20-30 years ago.

Workstation keyboards pre-dated DAWs, but boasted comprehensive sequencing and arranging capabilities, in addition to numerous onboard PCM-based sounds, to manage multiple simultaneous parts. The workstation formula perhaps solidified with the release of Korg's M1 in 1988—setting a high bar for all similar instruments that followed. Though these machines may often lack universal connectivity compared to standard computers, the common thread that links them together is in the completeness of their creative feature sets. You can create sounds from scratch, intermingle them with external sounds or instruments, and, in one way or another, internally record or store the results via MIDI, audio files, or other storage methods.

[Above: Korg's M1 Workstation Keyboard. Image via Perfect Circuit's archives]

Clearly you'll find no shortage of musical computers out there—so long as you have a sufficiently broad definition of what one can be. However, even when considering the significant advances in microprocessing technologies, the idea of a specialized computer devoted to making music is not a new concept. In fact, turning back the wheels of time to before the widespread adoption of powerful personal computers throughout the 1980s and 90s, it wasn't uncommon for big studios to drop serious cash on equipment to be among a select few on the cutting edge of technology. Fairlight's CMI and New England Digital's Synclavier are perhaps two of the most well-known examples, but even niche makers were exploring the possibilities of computing within musical contexts, as seen with instruments like Don Buchla's exceedingly rare 500 Series systems.

Systems such as these were prohibitively expensive for most, but the introduction of various home and personal computer platforms throughout the 1980s was making new technologies more accessible. These machines weren't nearly as specialized and certainly more catered towards general-purpose tasks out of the box, just like buying a computer or tablet now! But similarly to today's computers, you could easily turn your device into a music-making machine with some additional software and equipment. This is what makes the CX5M so interesting, and as we'll come to see Yamaha went above and beyond to produce their own peripherals, ROM programs, and, of course, a dedicated, pre-installed FM synthesizer cartridge.

Yamaha: From Synthesizers to Computers, and Back Again

If you know a thing or two about the history of synthesizers, you likely know that Yamaha's DX7 dominated the 1980s synth market. But if you are unfamiliar, check out one of our previous articles on the history of the Yamaha DX Series.

[Above: Yamaha's DX7 FM synthesizer. Image via Perfect Circuit's archives]

Following the runaway success of the DX7, Yamaha was an unstoppable force of FM synthesis and produced an extensive catalog of digital instruments and accessories in the short span of a few years. This was partially an attempt to keep up with the incredible demand for the DX7, and partially an effort to streamline the complex parameterization these instruments require. But in some cases, it was also an opportunity for Yamaha to try out some new ideas outside of what was seen as their flagship product.

To facilitate the rapid development of such products, it is important to consider the broad scope of manufacturing that Yamaha has at their disposal. Beyond synthesizers, it's no secret that Yamaha produces an incredible number of different products—not only musical instruments from guitars to wind instruments and beyond, but also manufacturing divisions dedicated to motorcycle manufacturing, semiconductor development, and a variety of consumer electronics for home video and audio (including computers produced before the CX5M). With such diverse needs and interests, it has been necessary for Yamaha to keep tabs on trends and developments in the broader field of electronics and technology.

Synthesizers like the DX7 were just a small part of the greater adoption of digital technologies across the world. In Yamaha's home country of Japan, MSX was taking off as the predominant home computing platform of choice for both consumers and developers. Introduced in 1983, which was coincidentally the same year the DX7 was released, MSX was born from work between ASCII Corporation and Microsoft, and as such included an extended version of the BASIC programming language embedded in the computer's ROM.

In light of additions to the BASIC language, the hardware for MSX computers supported many different peripherals and ROM cartridges, opening up possibilities ranging from generating graphics to playing music and video games. Japanese corporations viewed home computers as an exciting new market worth exploring and were eager to find a way in. For Yamaha specifically, the extensibility of the MSX platform was a perfect match for a growing family of digital synthesizers—especially following their involvement in the development and subsequent introduction of MIDI.

In the United States however, MSX was eclipsed by the popularity of the Commodore 64, and other manufacturers struggled with introducing their home computers to American consumers—if they even dared to try. Had it not been so strongly marketed as a companion device alongside the DX7, it's hard to say whether or not the CX5M would have ever appeared in the US market. But as we'll come to see, the CX5M boasts some unique features both as a standalone musical device and configuration tool for the DX7, which makes it an intriguing reference point in the convergence of music and computer technologies.

CX5M Hardware Overview

For our purposes as a music technology blog, we're going to focus more on the CX5M's capabilities as an instrument and tool for synthesizers. But of course, we should mention that the CX5M is still an MSX computer at its core, and features standardized ports for connecting ROM cartridges and peripherals such as joysticks. This means that after an exhaustive session composing music or configuring sounds, you could easily pop in a video game cartridge to decompress or engage in other typical computer functions.

Beyond simply establishing a presence in an emerging personal computer market, Yamaha was interested in the development of a platform that could interface with their growing catalog of DX instruments—especially the flagship DX7. However, in noticing the possibilities of a computer as an instrument itself (and perhaps to motivate more sales), Yamaha decided to develop a dedicated FM sound module for the CX5M. For consumers, this was a huge point—you didn't already have to own a synthesizer to begin making music with the CX5M.

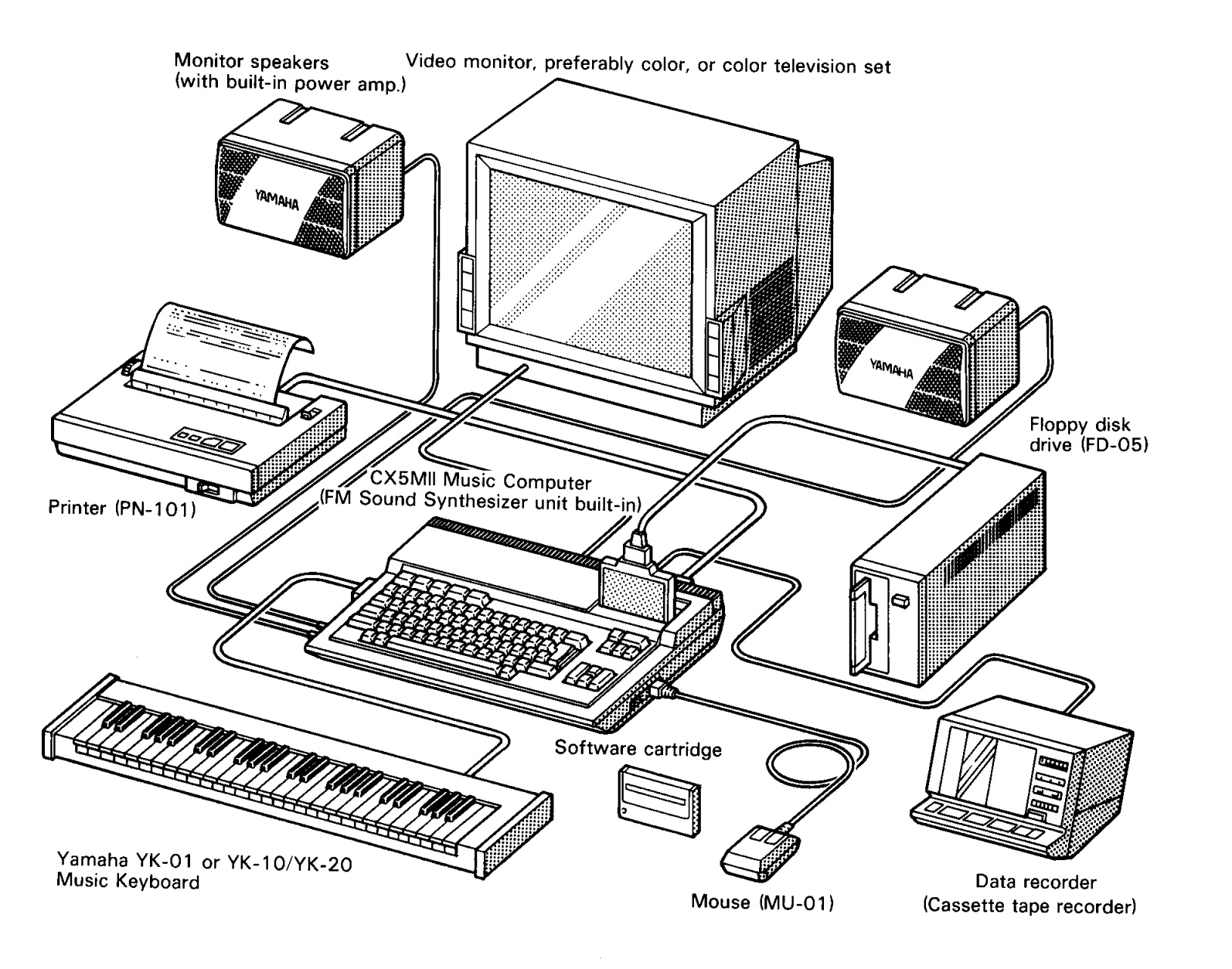

Throughout the CX5M's product lifespan, Yamaha primarily offered two different sound modules with their proprietary FM chips inside. Both the SFG-01 and SFG-05 featured identical synthesis capabilities as eight-voice, 4-operator FM synthesizers—simpler than the DX7's 6-operator architecture, but still enough to create rich textures and timbres. (Side note: if you're looking to learn more about FM synthesis as a concept, check out our aptly-titled article What is FM Synthesis?). The modules themselves are MSX cartridges to be installed in the bottom of the CX5M (or another MSX computer) and feature a variety of ports to connect MIDI devices and instruments. While audio is available via the rear port connection to a monitor display or TV, the SFG modules also offer direct audio outputs for cleaner monitoring and external recording.

[Above: Connection diagram from the CX5MII Owner's Manual]

To complement the SFG sound modules, Yamaha developed dedicated piano-style keyboard controllers for the CX5M. The YK-1 was the more affordable model with mini-keys, while the YK-10 was full-sized and a bit more robust in construction. These were not directly MIDI controllers themselves but connected to the CX5M with a specific cable and port on the side of the SFG module. Due to ROM limitations, the earlier SFG-01 sound module was rather limited, and its MIDI ports could only connect with a DX7 for configuration (more on that later). As such, the SFG-01 requires one of these YK controllers to access its sound engine. On the other hand, the upgraded SFG-05 was able to control external instruments with a YK controller connected as well as accept MIDI data from external sources, making it much more flexible.

Using the CX5M for Music

When the CX5M is powered on without a ROM cartridge in the top slot, it will always boot into the BASIC command line screen. But by running the "CALL MUSIC" command, you can access the internal ROM of the connected SFG module and gain access to the synthesizer. Because the SFG-01 had a much smaller ROM, its interface was rather barebones and simple. However, the later SFG-05 module featured a much more approachable graphic UI, even featuring a cute piano-style note display and neatly organized parameters. The CX5M that we spent some time with had the SFG-05 installed, so all the images you'll see alongside this article came from there.

Once the ROM loads, playing keys on the connected YK controller (or an external MIDI device on the SFG-05) will trigger sounds, and from there you can explore a variety of internal presets and operating modes. As far as usability goes, this mode is rather general-purpose and doesn't offer much in terms of parameter editing—you can't really get in deep with FM programming, but certain adjustments like portamento, transposition, and fine-tuning were available. However, perhaps for someone new to music or synthesis in the 1980s, it was a solid point of introduction and a number of features were useful for personal practice and musical fun at home.

All versions of the CX5M shipped with 48 preset sounds, but the later SFG-05 provided additional sound banks to be programmed by other ROMs (more on this later). Compared with many of the famous DX7 presets, the 4-op FM synths generally lacked that extra bit of sonic spice due to the smaller number of available operators. Despite this, the SFG modules were certainly adept enough to convey the versatility of FM, as the factory sounds included everything from pianos and organs to brass, woodwinds, and special effects patches.

There were also different playing modes available, allowing the SFG module to play sounds monophonically or polyphonically. The SFG sound modules supported multitimbrality, meaning that not only could you play multiple polyphonic voices, but voices could be assigned to distinct sounds. As such, the polyphonic mode allows you to assign MIDI channels for up to four different layers, yielding plenty of opportunities for multitimbral fun. The monophonic mode allows you to blend two sounds and charmingly features an auto-accompaniment option with a small selection of drum grooves and comping rhythms to jam along with. And with the onboard loop recorder, you could easily lay down an idea and hear the CX5M play it back to you—an exciting thing to experience in the mid-1980s!

CX5M ROM Cartridges

Thanks to the CX5M's MSX architecture, it's easy to swap in a different cartridge and load up alternative ROMs beyond the default music engine. While practically any compatible cartridge could be used, Yamaha produced several additional programs to maximize the musical usefulness of the CX5M specifically—further contributing to the robust ecosystem of DX instruments at the time. We got to spend some hands-on time with three of the earlier Yamaha cartridges, but there were many more produced over the CX5M's lifespan so this article isn't an exhaustive list of everything available.

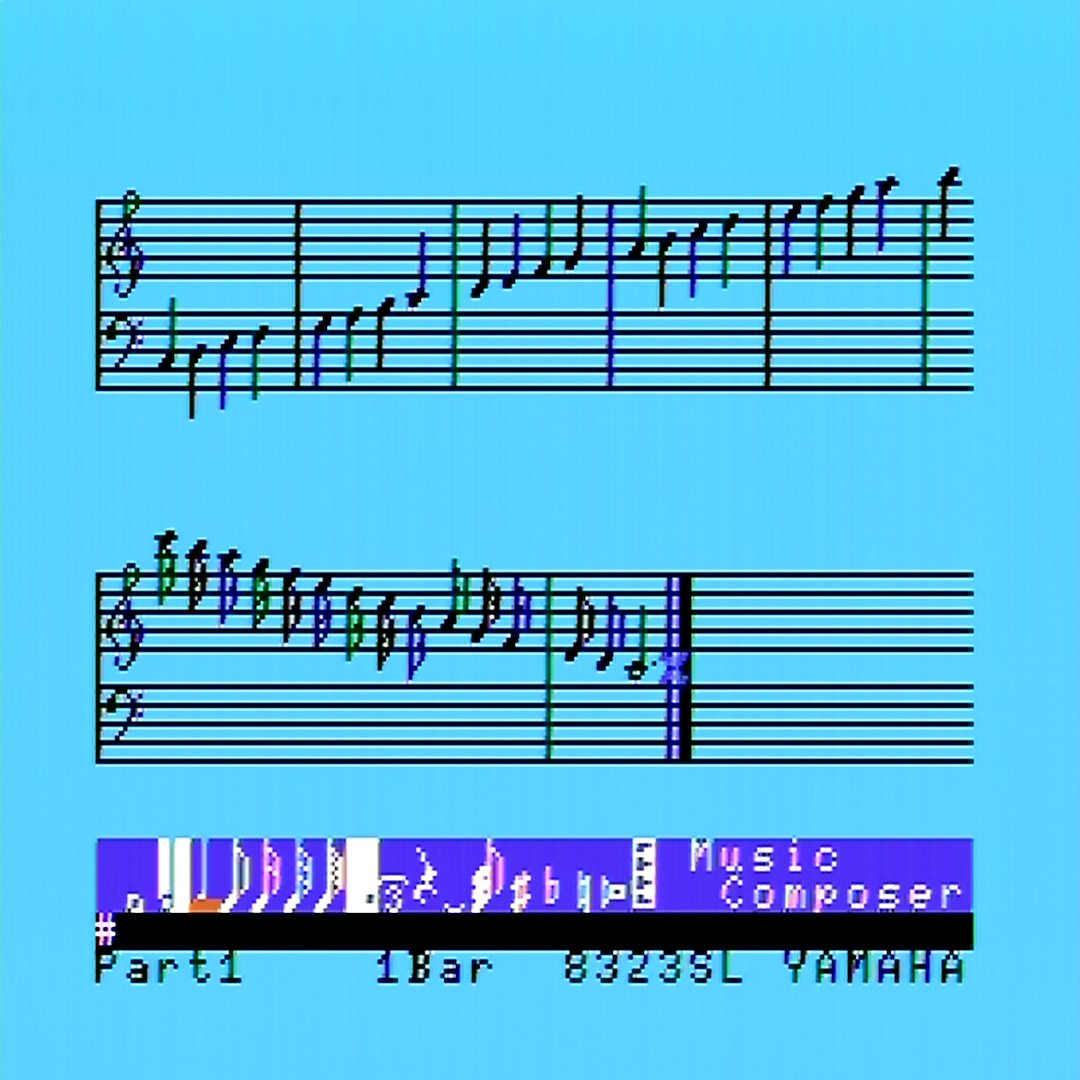

Where possible we'll pepper in images and audio recordings from the different cartridge programs to give you an idea of what using these ROMs is like. Keep in mind that we're pretty spoiled by today's high-resolution displays, crisp OLED screens, and generally more refined methods of generating graphics and user interfaces. That said, it's rather interesting to look back 40 years and see how Yamaha imagined graphical interfaces for editing FM sound engines and arranging music.

YRM-101: FM Music Composer

Predating modern scorewriter software and DAW-style piano rolls, the YRM-101 FM Music Composer cartridge was an early musical score-based composition program designed to facilitate the writing and arrangement of music. Leveraging the polyphonic and multitimbral capabilities of the SFG sound modules, it was possible to build out multi-part compositions and marvel at the CX5M's full musical power.

While this program might not have aged as well as some of the others in terms of usability, it was still an important inclusion in the CX5M's MSX ROM library. Of course, these days you'd likely just write notes into your DAW's piano roll and MIDI clips or turn to an application like Finale or Sibelius if you need traditional music notation. But there's something to be said for experiencing an instrument as it was at the time of its release, and there's no better way to do so than with the FM Music Composer program.

YRM-102: FM Voicing Program

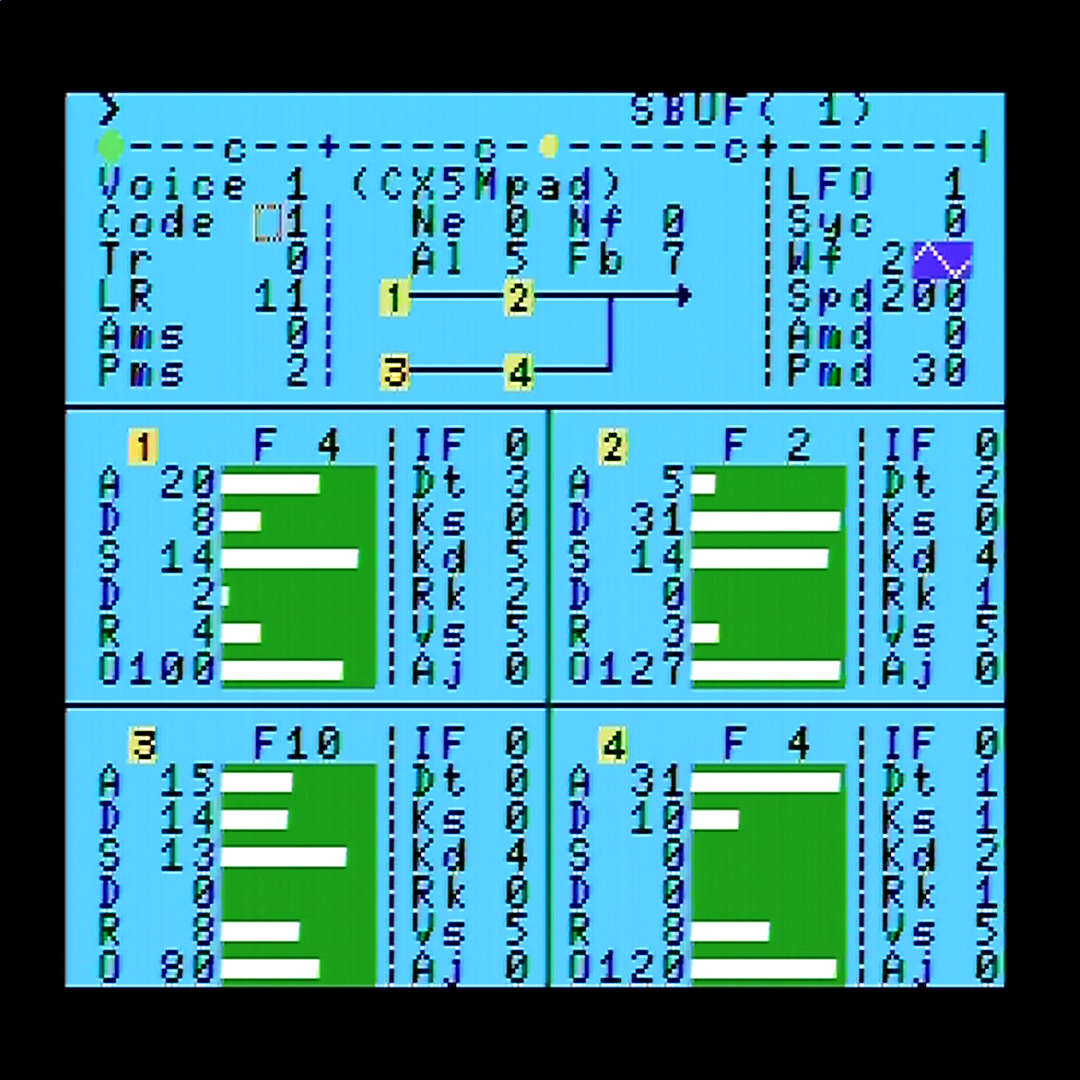

If the CX5M's internal sound ROM didn't satisfy your needs to tweak sounds, the YRM-102 cartridge has everything you've been missing. Aptly named "FM Voicing Program," it's the ROM of choice for those interested in sound design and offers some key insights into how the SFG module's synthesizer works.

Again, you can find more thorough overviews of FM synthesis in other articles on our blog, but we can at least offer you some quick technical points for using the SFG-01 and SFG-05 synthesizers. Each of the eight voices features four operators, which translated from FM jargon could be equated to an oscillator on other types of synthesizers. The key distinction is that an operator isn't just an oscillator but also features an amplitude envelope, determining how much of the oscillator signal is directly heard or used to modulate another operator. Different arrangements of operators are called algorithms, and each one can yield decidedly unique timbral results for any given patch.

While the UI might not be as refined as modern FM hardware or software synthesizers, you still have access to practically every parameter the SFG modules offer. Navigation is handled with the CX5M's arrow keys, and parameters are easily modified with the numerical and return keys. Since this is an early digital synthesizer working with limited memory, most parameters are restricted to three or four-bit values (0-7 or 0-15), with a handful offering even more range. Of course, a lot of these values don't directly correspond to musical units like hertz or seconds, but rather reference data stored in lookup tables within the FM chips. As such, you won't find the precision of modern instruments but the range of possible sounds is still broad enough to facilitate highly flexible results.

If you've ever used any of Yamaha's other 4-operator FM synths of the era, like the DX21, TX81z, or DX11, you'll likely notice a lot of similarities (and quirks) in operation and sound. For example, ranges and values used in parameters like LFO settings, algorithm selection, and detune correspond to the same features on those other devices. Similarly, you'll notice the attack, decay, and release parameters of the envelopes are inverted compared to most other synthesizers—their fastest times are available at the maximum setting of 31.

One nice thing to note is that this program allows you to access the internal firmware of the SFG module, and with the SFG-05 you can actually switch to the bank of user sounds created with the FM Voicing Program and enjoy your own custom sounds. From there, you can easily layer them up in multitimbral patches and subject them to external controllers.

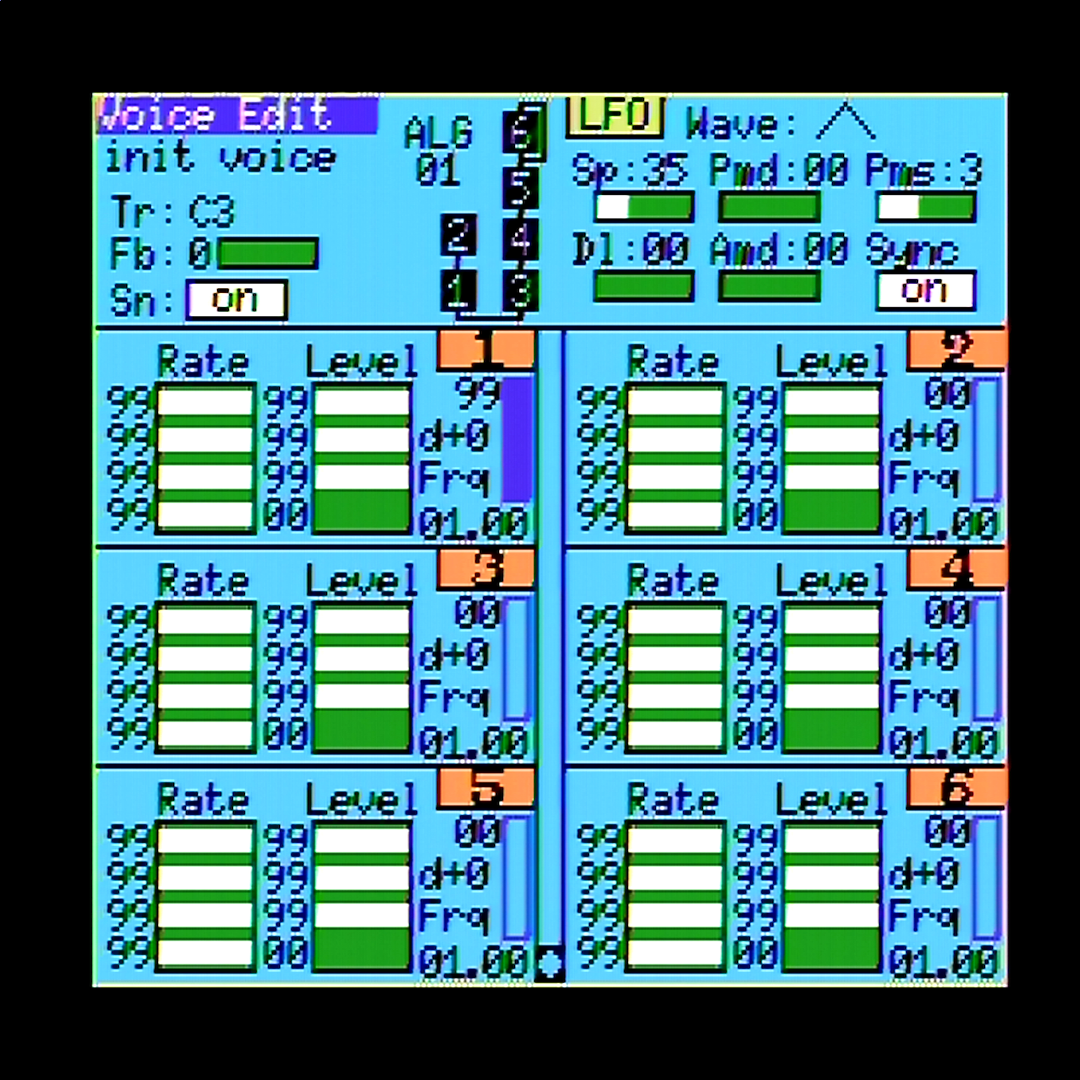

YRM-103: DX7 Voicing Program

It's conceivable that this cartridge was a primary marketing point for the CX5M—the DX7 was such a hit among professional musicians that the ability to more easily develop and program sounds was likely desirable. For all of its capabilities, the DX7 quickly earned its reputation as being somewhat tedious to program, infamously leaving many feeling disinclined to venture beyond the (very good) factory presets. As such, the DX7 Voicing Program offered a visual alternative to the buttons and data slider programming interface of the DX7.

Similar to the FM Voicing Program, the DX7 Voicing Program features a cyan-heavy interface, though obviously the layout and available parameters are quite different. This program also facilitates the organization of sounds into program banks and cassette-based preset storage. Of course, today there's no shortage of librarian software applications, modern preset cartridges like Hypersynth's Hcard-701, and even hardware programmers such as the DT-7 from Dtronics, it's easier than ever to curate sounds for a DX7. But, like with the FM Music Composer program, there is something to be said for using the CX5M as authentically as possible if that's something you're interested in doing.

It goes without saying that the CX5M's capabilities have been eclipsed many times over by newer computers, tablets, and even smartphones. But you have to give Yamaha credit for imagining a holistic ecosystem of electronic musical instruments and products and striving to explore the possibilities of, at the time, cutting-edge technology. Even now, it's fascinating to look back on the CX5M and appreciate what it could do at the time it was released, and appreciate how far computers have come since!