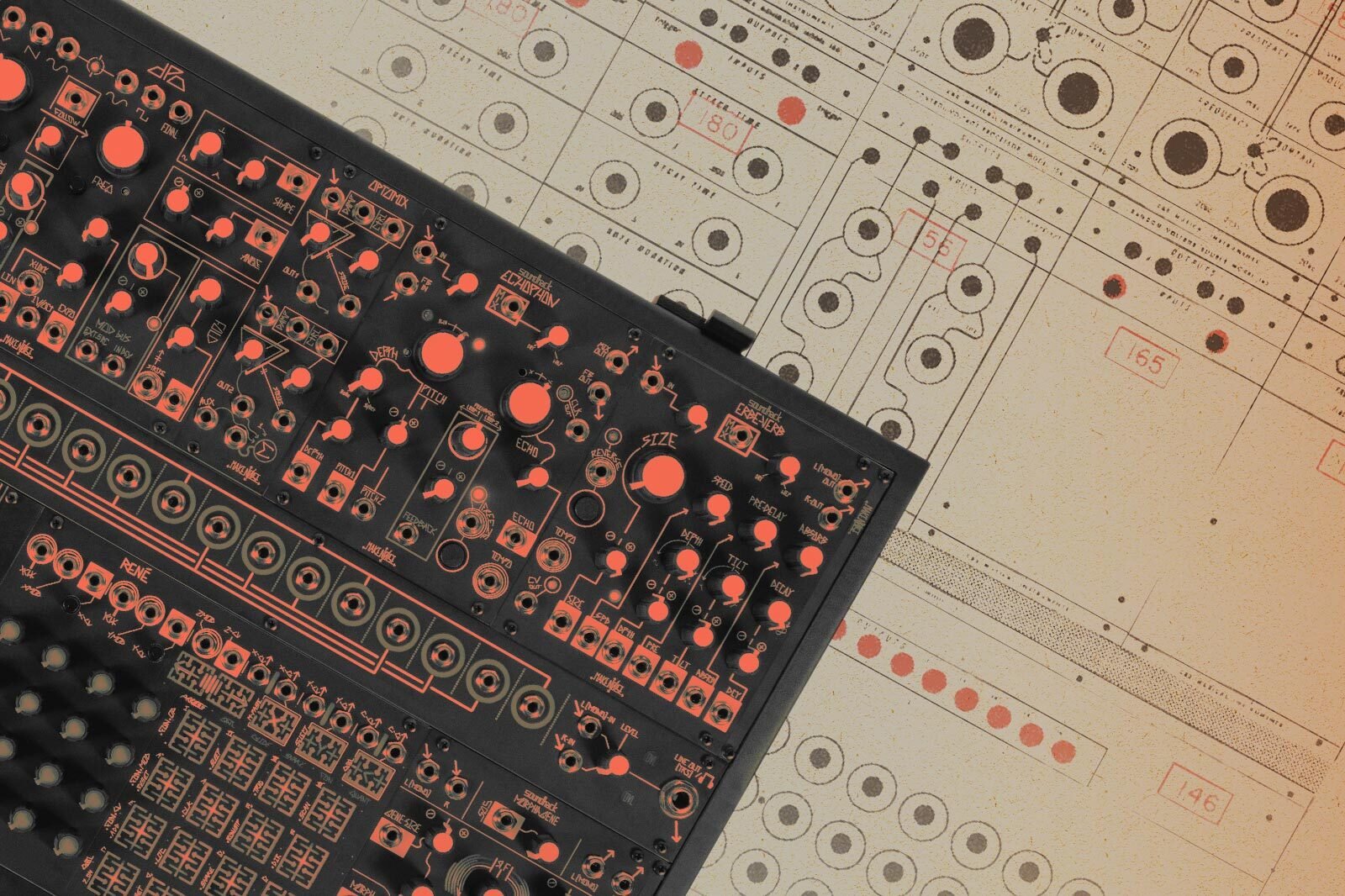

Let's start with a simple, direct definition first. What is a modular synthesizer? A modular synth is an electronic musical instrument comprised of several individual modules. The player connects patch cables between these individual modules, creating a signal path that allows the instrument to make sound. Because of the ease with which patch cables can be re-arranged, a modular synth can produce a wide range of sounds and can be played in a vast number of ways—and in fact, even a single modular synthesizer can sound and behave entirely differently depending on how it is patched.

Today, the most common format of modular synthesizer is called Eurorack. Eurorack modular synths have become so popular in part because of a shared set of production standards (e.g. standardized dimensions and power supply specifications); these universally agreed-upon specifications have made it possible for instrument designers to develop a broad set of tools, and for musicians to pick and choose which modules are right for their own music...even building synthesizers comprised of modules from multiple manufacturers. This means that you can pick and choose modules that you personally find inspiring—eventually creating a synthesizer that is entirely unique, purpose-built to work for your own music.

Because the landscape of Eurorack synthesizers has grown to be so rich and varied, and simply because of natural flexibility, modular synths are now an appealing and valuable tool for sound designers, performers, tinkerers, and producers who are passionate about building unique sounds. But modular synths weren't always quite like this—so in the remainder of this article, we're going to take a look at where modular synths came from, how they have developed over time, and what they mean for artists today.

Where Did Modular Synths Come From?

When you try to imagine a synthesizer, what sort of image comes to mind? For many, a synthesizer is an electronic musical instrument with a keyboard—and maybe some knobs, switches, or sliders that allow you to change some aspects of the sound it makes. However, this isn't how synthesizers always were; in fact, in many ways, modular synthesizers were the precursors to this sort of instrument.

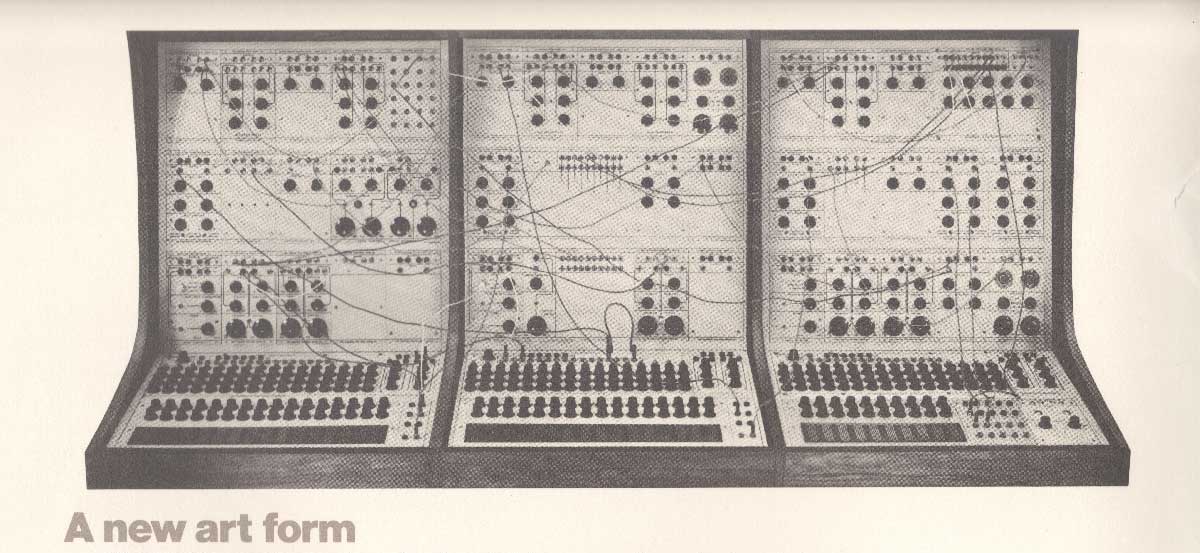

A photo of the WDR studio in Cologne—the workplace of Karlheinz Stockhausen and others. Image via 120years.net

A photo of the WDR studio in Cologne—the workplace of Karlheinz Stockhausen and others. Image via 120years.net

But let's take things back a step—to a time before the invention of the synthesizer: to the 1940s and 1950s. Electronic music studios became relatively common in this time period; these were often related to schools, radio stations, or television broadcast. For the most part, these studios were the workplaces of experimental musicians, who used a combination of reel-to-reel tape recorders, radio broadcast equipment, electronic test equipment, and purpose-built electronics to record and manipulate sound. Much of the work involved detailed creative tape editing—reversing tape, playing it back at different speeds, even bouncing audio between multiple tape machines for a variety of purposes. Though many musicians became quite skillful at working in this way, the workflow wasn't for everyone: it wasn't nearly as immediate as, say, playing a musical instrument, or putting pen to paper to compose a new piece of music.

As such, composers and engineers began to imagine how the practice of electronic music composition could be refined with new technologies. If they didn't need to rely on repurposed broadcast and test equipment—if there were a device designed for the purpose of composing electronic music—perhaps they could compose with greater immediacy, and could better translate the sounds they imagined into finished pieces of music. This general idea spawned a wide range of unique, one-off devices, from Harry Olson & Herbert Belar's RCA Synthesizer to the countless inventions of Raymond Scott, Hugh Le Caine, Harald Bode, and others. However, a couple of particular developments are now seen as a turning point at which the modern synthesizer really emerged—and these developments are the early musical inventions of Robert Moog and Don Buchla.

In the mid-1960s, Bob Moog began a collaboration with musician Herb Deutsch in which the two imagined and built an electronic instrument that combined the sonic approach of a tape music studio with the real-time performability of a traditional instrument. Similarly, on the West Coast of the United States, Don Buchla was collaborating with San Francisco Tape Music Center composers Morton Subotnick and Ramon Sender to realize their idea of an electronic music "easel," a device which would allow composers to forego extensive use of the tape recorder in favor of creating more extensive passages of music in real time. (See below: a brochure image of an early Buchla system.)

What is particularly notable here is that each of their approaches were actually quite similar. Eventually, each designer created a device comprised of several individual modules of standardized dimensions in a single chassis, all connected to a single power supply. The modules were not unlike the types of devices found in a "classical" tape music studio (oscillators, filters, and the like), and these modules were interconnected via a series of patch cables—again, much like the individual devices in a tape music studio. These were some of the first modular synthesizers. Eventually, each of these inventors went to business selling custom modular synthesizers to schools, studios, bands, and individual musicians, providing consultation along the way to ensure that the set of modules in a customer's system was the best fit for their musical purposes.

The key innovation here wasn't necessarily about modularity, though. Instead, the revolutionary concept behind these instruments was about control voltage. Control voltage allows the use of independent modules to affect one another's behavior—somewhat like an analog precursor to MIDI, or automation in a DAW. While some modules in a modular synthesizer are dedicated to producing sound or processing sound, others are designed specifically to produce different types of control voltages, from repetitive cyclical voltages to user-definable sequences of voltages to triggerable one-shot voltage shapes. This is what made modular synthesizers such a big deal: they made it such that changes in sound could be easily programmed and altered on the fly, whereas similar sound manipulation in the context of tape music would mean multiple edits, bouncing audio between multiple tape decks, and a lot of time lost to these technical processes. With the modular synth, you no longer needed to splice together multiple pieces of tape to make a specific sequence of pitches, for instance: instead, you could simply plug your sequencer's control voltage output to your oscillator's control voltage input et voila! You can move on to your next musical idea.

An expanded Model 12—a small Moog system from the early 1970s

An expanded Model 12—a small Moog system from the early 1970s

So while much of the appeal of early modular synthesizers did have to do with their unique sonic possibilities, one of the most immediately impactful aspects of their design was simply their immediacy. By allowing artists to rapidly realize new sounds and musical ideas, their creative process could flow more continuously and spontaneously. It was the first time that musicians were able to have this sort of immediate back-and-forth, iterative process with a machine, where they could sit back and listen to how their musical ideas were unfolding, and then tweak as needed until they got it right. This sort of creative feedback, in which the composer is also simply an observer, is perhaps one of the most significant impacts technology has had on the creation of music altogether.

It's worth noting here that the early history of electronic music is rich, varied, and constantly evolving. We're talking here about events that unfolded within the last century. As such, the way that we historically contextualize all of these events is continually shifting and changing directions—as it should! Though we're endlessly grateful for their work, it's unfair to imply that Don Buchla and Bob Moog are solely responsible for the creation of the synthesizer. If you're curious to know more about this murky, knotted history, I'd like to suggest you check out our article Who Really Invented the Synthesizer?, in which we take a closer look at the instrument's development and the climate from which it emerged.

What Happened to Modular Synthesizers?

Despite their immense sonic potential, modular synthesizers didn't become widely popular instruments when first introduced. They were expensive, physically unwieldy, and complex to operate—so for most musicians, these devices remained inaccessible.

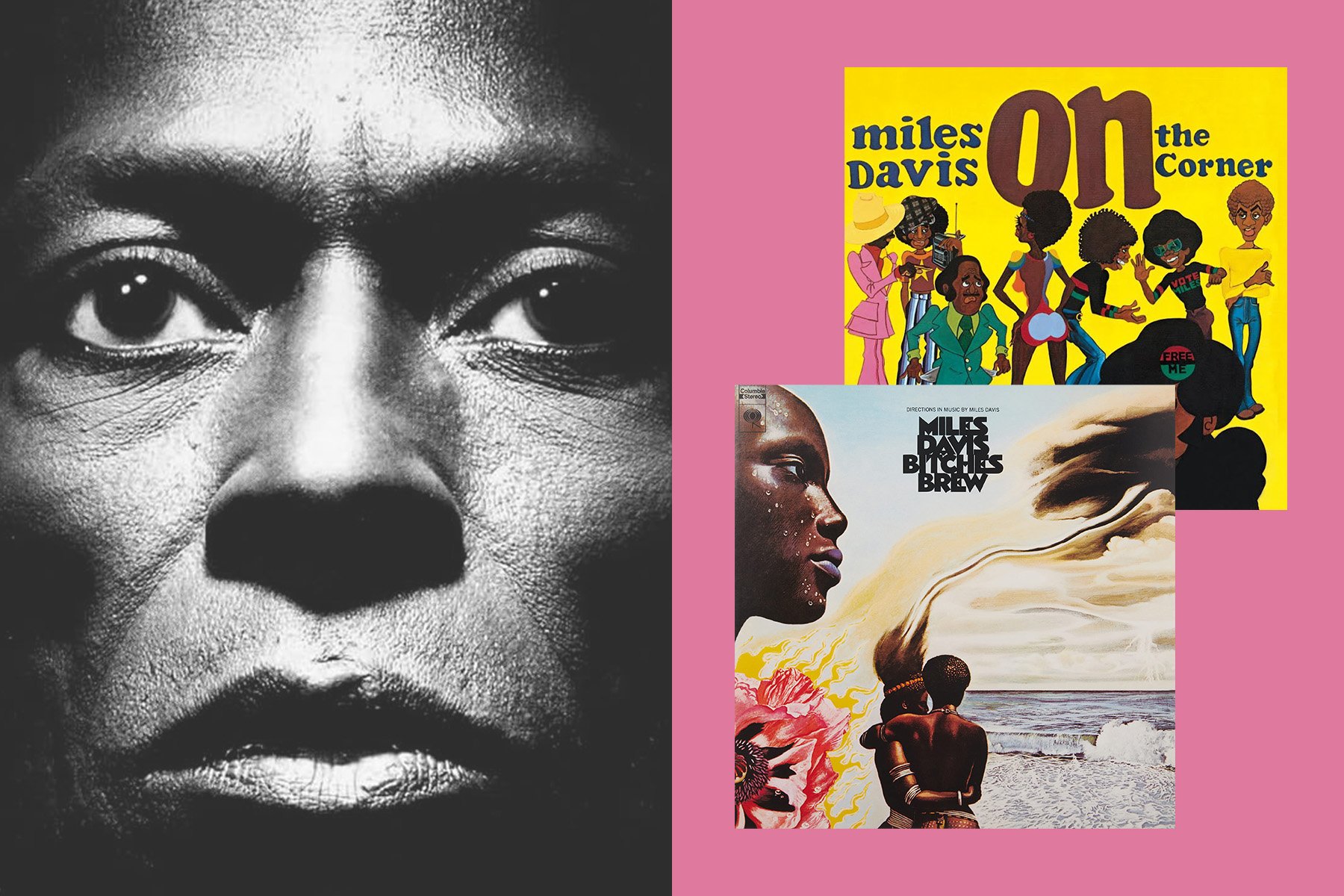

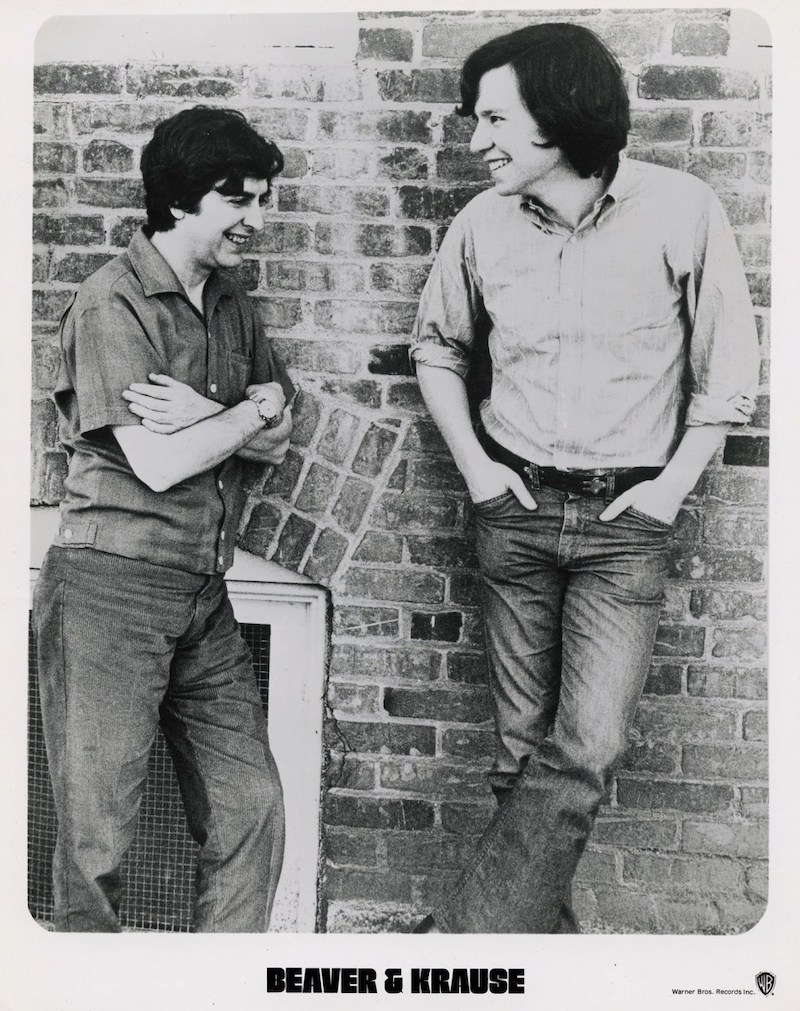

However, given their slow creep out of the world of academia and into mainstream pop music, the demand for synthesizer sounds was growing. As such, many major studios employed session musicians like Paul Beaver and Bernie Krause—who would often come into the studio and provide synth sounds for other artists' records (and for a wide range of films). This was all well and good for a while, but as time went on, even in these contexts the synthesizer shifted from being a box of sonic mystery to being an instrument that produced familiar, if not still relatively novel sounds. Once a handful of early records started using the modular synth, it became common for bands or record producers to demand "the sound from that The Who record," etc. And of course, Wendy Carlos's album Switched-On Bach was profoundly influential, introducing a huge audience to the sound and musical capabilities of the synthesizer. As such, in pop culture, the idea of how a synthesizer sounded actually crystalized fairly quickly, and the endless horizons the instrument offered were no longer its primary attraction.

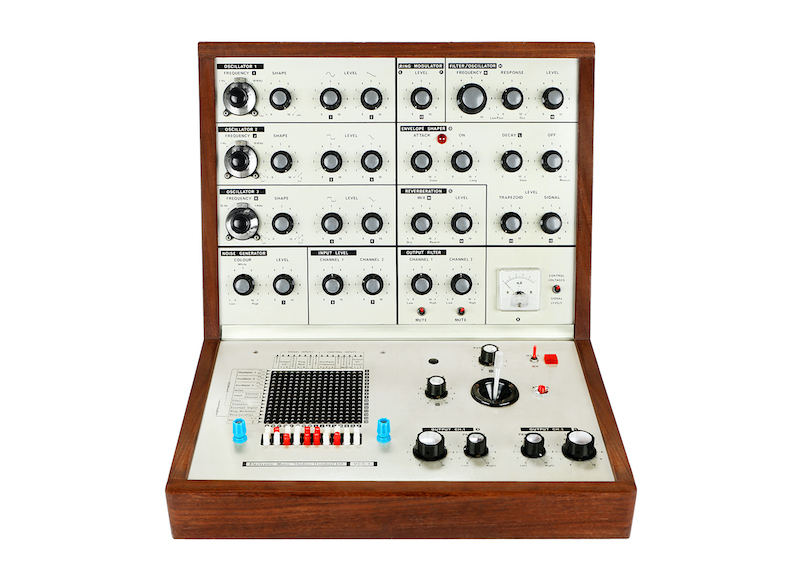

By the early 1970s, every synthesizer designer (by then, including ARP, EMS, and others) faced a related dilemma: the number of people and institutions willing to spend the money for a custom modular system was dwindling. In order to stay afloat, they needed to broaden their market—and they all eventually did so by attempting to design instruments that were more affordable and easier for musicians to understand. Each designer approached this conundrum in a unique way; for instance, the semi-modular ARP 2600 and EMS's VCS3 offer markedly different approaches to a "simplified" synthesizer design. However, perhaps one of the most notable such attempt was the Minimoog (1970).

The Minimoog's original design was spearheaded by Moog employee Bill Hemsath, who cobbled together a self-contained instrument from junk/discarded parts at the Moog factory. He originally did this for his own personal enjoyment, and introduced his small, quirky instrument to Bob Moog himself, who reportedly thought it was fun, but didn't see a market for it. Through a series of twists and turns (along with a relatively unstructured/open-ended work environment), Moog's engineers eventually turned Hemsath's idea into a production-ready instrument—one that, for the most part, discarded the concept of modularity. While early "portable" instruments from other makers still maintained a modular workflow (as with EMS VCS3's pin matrix, ARP 2600's semi-modular patch points, and the Buchla Music Easel's shorting bar patch bay), the Minimoog did away with this entirely, instead using an entirely pre-wired signal path.

In classic modular synthesizers, the instrument cannot make sound until the player has defined their signal flow with patch cables (also known as "building a patch"). As such, the user needs to have a strong grasp of synthesis and electronic music to even make a sound, let alone make music. But through the combination of the right number of sonic resources and the right panel controls, the Minimoog made it possible to achieve a significant subset of classic "Moog" sounds without the need for patch cables. By deciding on a fixed signal flow and allowing minor changes to the signal path using a series of knobs and switches, the Minimoog effectively swept the most complex aspects of modular synthesis under the proverbial rug—musicians could simply press a key, turn some knobs, and immediately make sound. Of course, it couldn't do everything that you could do with a full modular synth...but it could make the vast majority of the types of synthesizer sounds musicians were starting to hear on the radio, and it was considerably more affordable than its modular brethren. To make a long story short, the Minimoog became a hit.

EMS's VCS3—a much-loved early attempt at building a small, self-contained synthesizer

EMS's VCS3—a much-loved early attempt at building a small, self-contained synthesizer

Because early modular synthesizers were modeled after experimental electronic music studios (and because they sought to explore the new possibilities that electronics could offer), many early synthesizers featured playing methods unrelated to traditional music. While some early instruments did feature a black and white keyboard, yet others instead relied on different means of control. Buchla's early 100 Series instruments, for instance, employed sequencers, random voltage generators, and arrays of touch plates as a means of control; and while EMS did offer a keyboard controller for the VCS3, many players instead relied on the instrument's built-in joystick as a primary playing interface. But in many ways, the Minimoog turned the tide: more and more portable synthesizers began to emerge that relied on a fixed signal path and a built-in black and white keyboard. Instead of focusing on the flexibility of modular instruments, many designers instead made instruments that emulated this workflow—until eventually, the significant majority of new synthesizers were self-contained keyboard instruments. By the 1980s, for many, modular synthesizers already seemed like an outdated novelty...and by the 1990s they were all but extinct, with only a couple of niche manufacturers continuing to build analog modular instruments (for an interesting account of some of these, check out our article about the Synton Fènix).

So...Why Do We Care About Modular Synths, Then?

In the 1980s and 1990s, analog synthesizers nearly disappeared from the marketplace altogether. With the advent of affordable digital technology, many makers turned their focus to creating polyphonic digital keyboard synths, complete with patch memory, presets, and so forth. Of course, the core concepts of modular systems remained—after all, self-contained synths naturally evolved from modular synths—but many synthesizers became increasingly preset-based, became difficult to edit, and offered considerably less in terms of hands-on control.

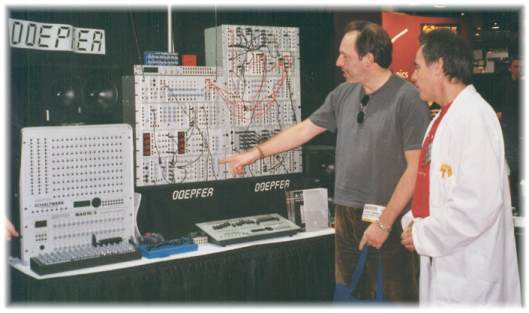

Dieter Doepfer (right) alongside composer Hans Zimmer at NAMM 2001

Dieter Doepfer (right) alongside composer Hans Zimmer at NAMM 2001

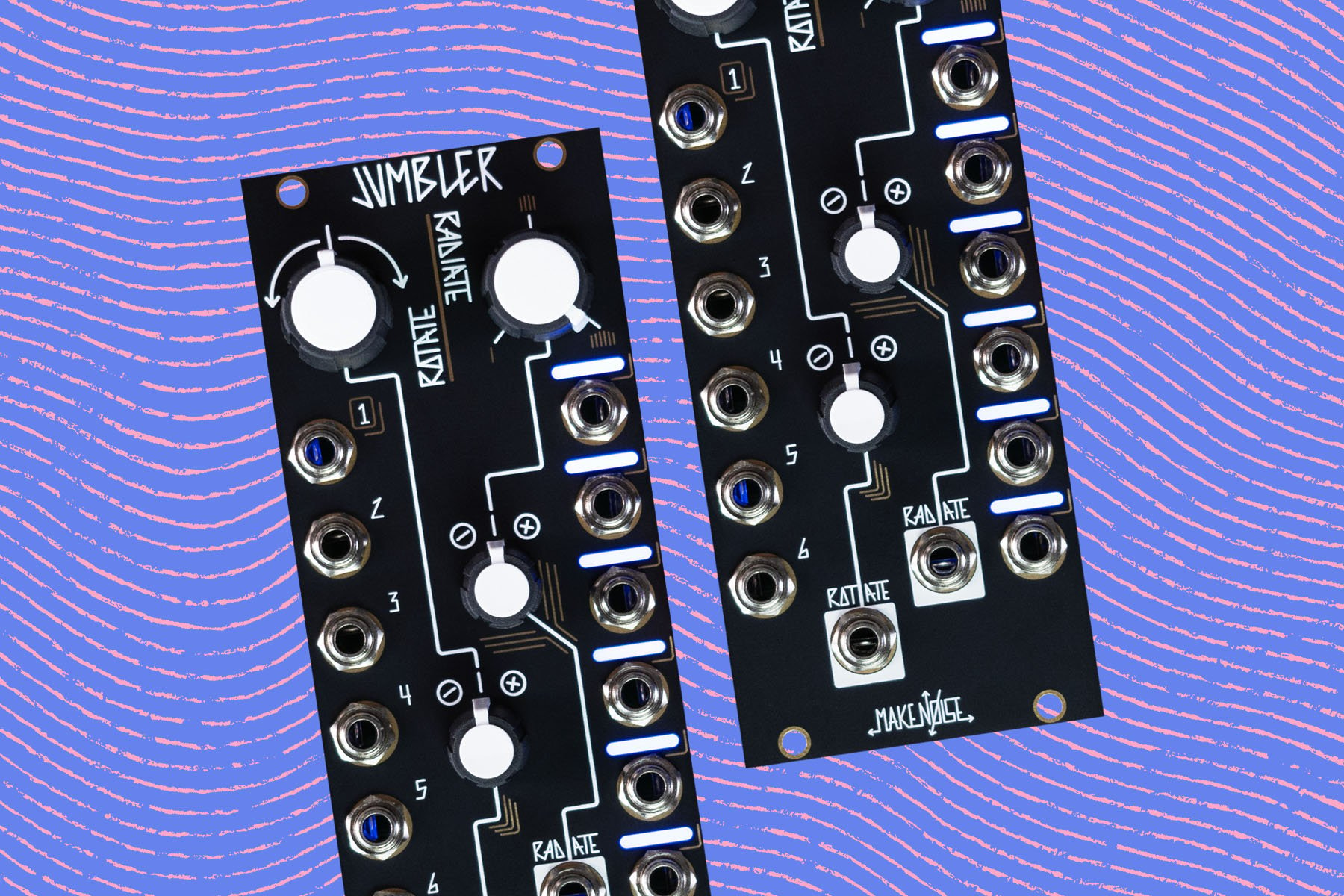

Modular enthusiasts never disappeared, though. Many musicians had "cut their teeth" on modular systems in academic environments or recording studios, and were anxious to return to the old ways of patch cables, knobs, and switches. By the mid/late-1990s, German instrument designer Dieter Doepfer had introduced his modern solution: the Doepfer A-100 System. The A-100 system didn't exactly follow the conventions of older systems—instead, Doepfer decided on his own set of standards for module dimensions, power supply requirements, patch cable type, etc. Doepfer did offer a quite complete complement of modules for a huge range of musical purposes—but perhaps his most important contribution to the world of synthesis was that the technical specifications for the A-100 system were so clear: once the systems began to catch on, other manufacturers (Livewire, Plan B, etc.) emerged, producing A-100-compatible modules whose functionality wasn't represented in Doepfer's own lineup.

From there, industrious young engineer-musicians began to develop modules to expand their own personal systems, gradually developing into full-fledged companies (The Harvestman/Industrial Music Electronics, Make Noise, Intellijel, etc.). It was here that the modern landscape of modular synthesis truly began to take hold: suddenly, the A-100 system was an open-ended format with an astonishing number of unique designers, each with their own sonic aesthetic and visual design.

And that's where we are today. Now generically referred to as "Eurorack," the A-100 ecosystem is by far the most popular and most sonically varied modular format to date. In fact, the open-endedness of Doepfer's format is one of the key elements that defines what modular synthesis means to us today. Remember: originally modular synthesizers were only user-configurable to an extent. If you could afford to buy a modular synth in the 1960s or 1970s, you only had a couple of manufacturers to choose from—and you would buy into their instrument exclusively. With rare one-off exceptions, there weren't third-party developers designing modules for Buchla, ARP, or Moog systems...and as such, once you had your system, you were essentially limited to what it contained—and furthermore, you were limited to the sonic possibilities offered by its designer's own aesthetic sensibilities.

But that isn't how things are today. These days, we usually think about modular synths differently: they're much more open-ended than they have been at any point in the past. Now that we have a rough idea of the history of these peculiar instruments (and how they got to where they are today), I'd like to re-approach our original question: what is a modular synth?

So What is a Modular Synth...and What CAN It Be?

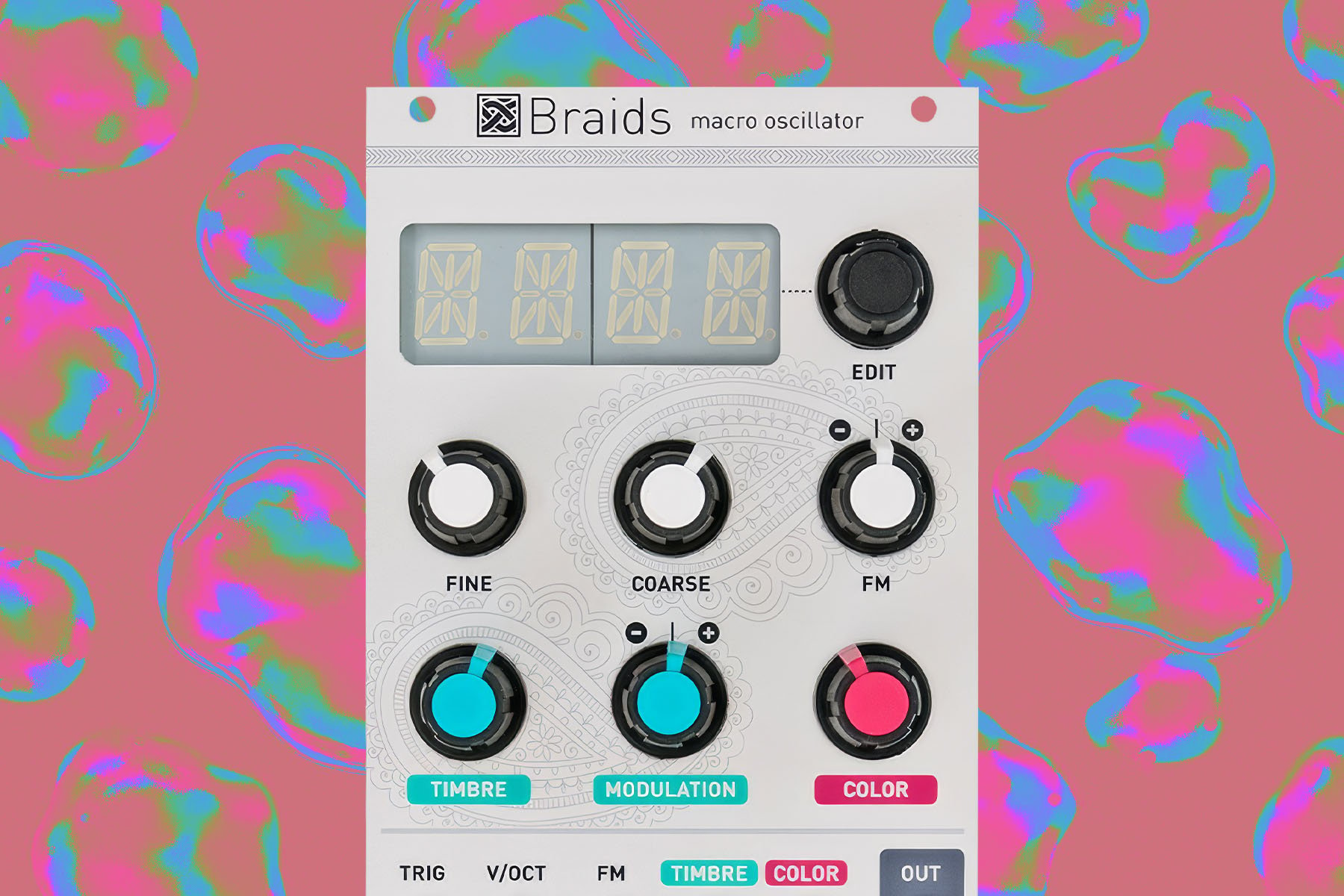

The core of the answer is the same: a modular synthesizer is an electronic musical instrument which is comprised of individual modules. Each module serves a distinct musical function, and groups of modules can be interconnected using patch cables, enabling the player to create custom signal paths at a moment's notice. This differs from self-contained synthesizers in that the signal routing is much more open ended: rather than having to stick to a manufacturer's proscribed internal structure for an instrument, users can effectively make decisions about how the instrument should work at any given moment...in effect, designing their own instrument.

This is why modular synthesizers have become so popular. Despite some of the technical hurdles musicians can face when first getting up and running, the rewards can be tremendous. By selecting from a range of thousands of modules from hundreds of manufacturers, musicians are able to pick and choose the musical functions that matter most for their own music—and from there, they can completely change the way their own instrument behaves simply by patching it in a different way.

Because of this, a modular synthesizer can be basically anything you want it to be: it can be a way of creatively processing external instruments. It can be a way of designing your ideal personal synth sound, drawing influence from several different approaches to sound design. It can be a way of mangling and sequencing samples, like a super-powerful drum machine/sampler/groovebox. It can be a way of creatively mixing sounds coming from your DAW. It could even be a way of establishing musical "rules" that allow you to create entire pieces of music at the push of a button.

Perhaps one of the most profound implications of all of this—and perhaps one of the strongest reasons for their popularity—is that modular synthesizers are a simple and very direct way to enjoy making music and working with sound...even if you don't have any other musical training. Electronic music as a broad genre has had an enormous cultural impact, in that the evolution of music technology has made it such that entire pieces of music can be made by anyone. From samplers and affordable drum machines in the 1980s/1990s and onward to the advent of affordable home recording technology, electronic music tools have made it possible for a single musician to be an entire band, a recording engineer, a producer, and more. You no longer need to rely on luck or record labels in order to exercise your creativity, and you don't need to have years of musical training in order to make music.

I see modular synthesizers as strongly aligning with this sentiment. Though modular synthesizers may not be the most easy-to-use instruments out there, I think it's fair to say that they are fairly immediate—that is to say, you don't need to practice for years in order to make interesting sounds that you (and others!) can enjoy. Because they allow you to create instruments from scratch, they give everyone the ability to define the rules of their own music: how does it sound? How do rhythms develop over time? Do melodies matter? Is it loud, or quiet? Intricate, or sparse? Fast-paced and intense, or patiently evolving? Without needing a musical or strongly technical background, modular synthesizers can even allow you to sit back and observe your music unfolding before your very ears...allowing you to engage as a listener during the compositional process. This means that anyone who enjoys listening (and a little bit of knob-turning!) can make music—and that the music they make could sound like nothing else before it.

Looking to Get Started with Modular Synths?

Of course, in this article, we've mostly been talking about modular synths' history and why you might want to use them...but we haven't really touched on the technical details of how modular synths work. Luckily, if you're trying to get started with modular synths, we do have plenty of other resources available.

If you're planning your first modular system, we strongly recommend checking out this article, in which we talk with musician Sarah Belle Reid about how to take your first steps into Eurorack—and after that, check out our dedicated articles about Eurorack cases and Eurorack power supply basics so that you can get up and running with confidence. And of course, if you're looking for deeper discussion about synthesis techniques in general, check out our series Learning Synthesis, in which we offer extensive deep dives into how modular synthesizers work on a technical level. And of course, if you're ever looking to learn more about the wonderful world of modular synths, you can always reach out to us for suggestions & direction. All the best, and happy patching!