In the darkest days of digital synthesis, there came a time when people started to realize that something had been lost. In the clambering for the sound and convenience of samples, partials, wavetables and FM, old analog synths were discarded and all but trodden into the dirt. We had been enraptured by the shiny blank surfaces of endless preset sounds and enthralled by the possibilities of a limitless computerized studio. But we had lost the joy of simple waveforms and sacrificed a forest of knobs for the mouse of pain.

Into this space came Virtual Analog (VA).

The Birth of Virtual Analog

The idea of returning to the hand-finished wooden cabinets and fluctuating oscillators of the 1970s would seem like madness. This was the 1990s—the future—and the future was DSP. So instead of revisiting old analog circuits in their original form, clever developers saw that processors like those used to produce digital synthesizers could be employed to recapture the sounds and the joyfulness of the classic tones that shaped the 1970s and '80s. Meanwhile, the growing underground dance music scene asked why there was nothing they could buy that sounded juicy in a fat, squelchy analog way—and why seemingly nothing had knobs they could fiddle with.

Most of the analog synth industry had been killed off in the 1980s by cheap digital synths and samplers. But there was a growing interest in second hand analog synths; something about their sound pushed hard against the digital wash that was sloshing through the music industry.

So, digital synth manufacturers set about coming up with an analog-sounding alternative that benefited from all the advantages of digital synthesis and modern manufacturing while keeping that analog feel. Everyone remembered how much of a pain in the arse analog synthesizers used to be—while they may have been beautiful instruments, full of warmth and character, they were also chunky, heavy, unreliable, inconsistent, expensive, prone to overheating and tuning issues. You might require a whole truckload just to give you the different sounds you needed for a full live set. That entire headache could be replaced with a single Korg M1 or Roland D50. These instruments massively simplified touring; they had MIDI and multiple layers so that everything could be accurately replicated and recalled at the loading of a program. The impact was huge and transformational, and no one wanted to go back to how it was before.

However, coming back to my first line, something was lost in that transition, and musicians wanted it back.

[Above: the now-iconic Nord Lead, from Swedish firm Clavia...the first commercial Virtual Analog synthesizer. Images via Perfect Circuit's archives.]

Swedish company Clavia coined the term Virtual Analog Synthesis in 1995 with the introduction of the Nord Lead. It was the first large-scale, commercial synthesizer to use digital technology to create a computer model of analog circuitry. It wasn't enough to have a digitally generated "analog" waveform; what Clavia did was analyze analog circuits and create mathematical simulations of the electrical signals generated within the components. This attention to detail gave the sounds a life and character that was far more convincing than the analog synth presets in other digital synths of the day. But it was still digital, which meant it had all the advantages of the digital control and consistency that musicians had come to rely on, but with knobs. As analog circuits were being emulated, it made complete sense that the emulation would extend to individual controls protruding from the synthesizer.

So, what we have is digital reliability, recallability, and connectivity with a believably analog sound and tactile control. It's the best of all possible worlds.

The other big advantage over regular analog synthesizers is that they were casually polyphonic. To do polyphonic in analog you have to physically replicate the synthesizer for every voice, adding massively to the cost, build time, and complexity of the instrument. Polyphony on a VA synth, though, was simply down to how much room you had in your processor—and as such, these instruments were far more affordable and accessible than instruments of similar capability ever had been. As such, many current musicians cut their teeth on this early era of virtual analog instrument.

Early Examples of Virtual Analog Synthesis

Coming hot on the heels of the Nord Lead was the remarkable Korg Prophecy. Korg had spent a few years producing really dull synthesizers such as the X and i ranges, which were bland, sample-based do-everything type workstations. But in 1995 someone at Korg was fiddling with physical modeling and virtual analog techniques and stuck it in an awesomely playable shell. The monophonic Prophecy had a ribbon controller, weird cylindrical modulation wheel, and just enough knobs to make it interesting. It sounded fantastic and was a huge hit in dance music.

[Above: the Korg Prophecy, a 1990s physical modeling/virtual analog synthesizer. Images via Perfect Circuit's archives.]

A polyphonic version wouldn't come along until the Z1 in 1997. Interestingly, Korg released the ultimate in period-appropriate, bland-but-powerful workstations, the Trinity, at the same time—and you could get a Prophecy card for it that ran the whole synth engine. Such is the versatility of VA.

Meanwhile, Roland was not going to miss out on this emerging scene. They had already given us the unwieldy JD-800 in an effort to recapture some of the hands-on analog vibe that had been lost with digital synths like their own D-50. And so, they were definitely up for emulating the feel of analog while pushing forward with digital developments—something they still do some 30 years later. What they came up with was the magnificent JP-8000.

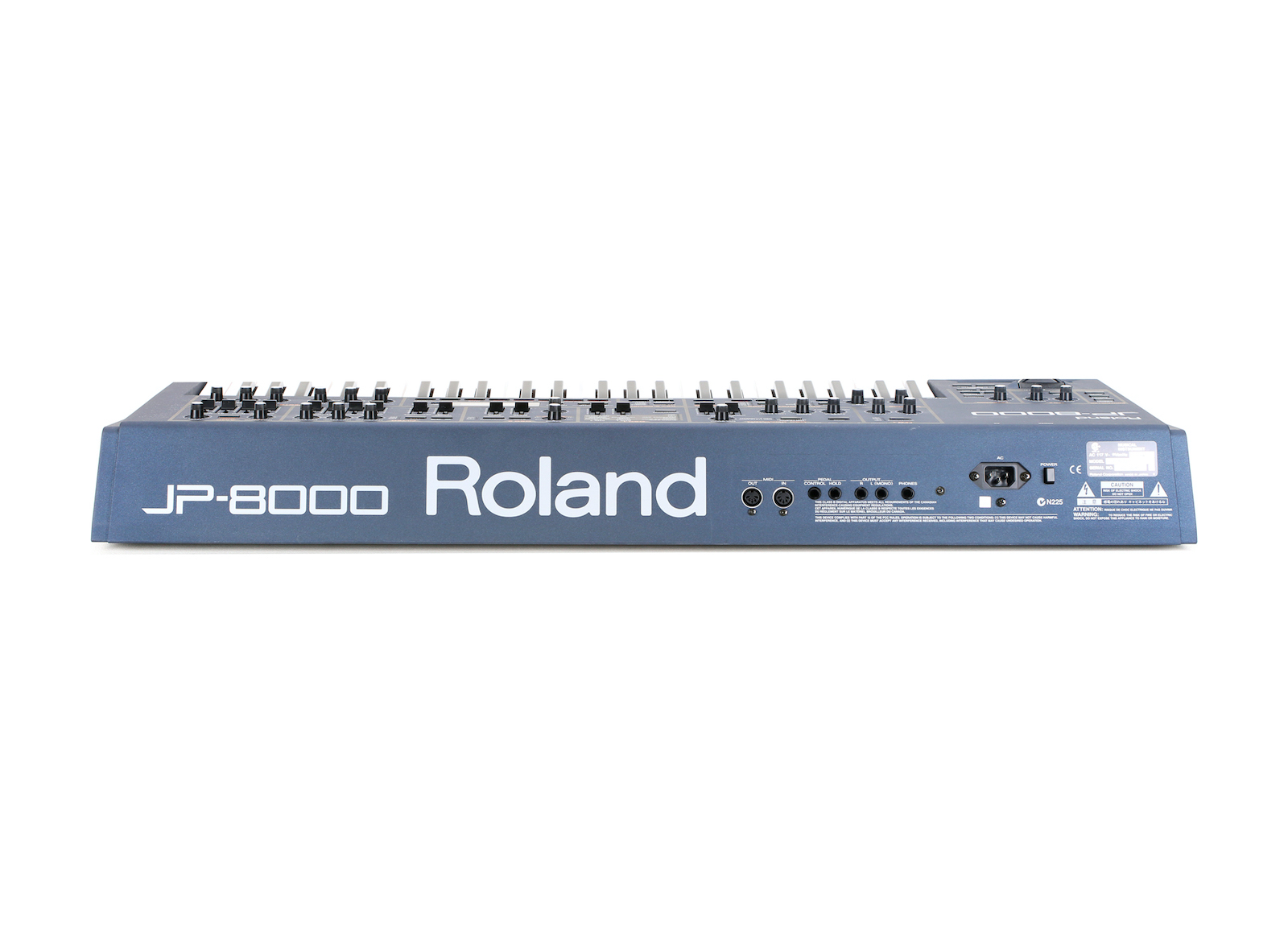

[Above: the Roland JP-8000—a machine that defined the sound of trance music. Images via Perfect Circuit's archives.]

This was the best-looking synthesizer we'd seen in years, hampered only by the '90s aesthetic that made everything plastic and bumpy. It harkened back to the Junos with the layout of controls and playability and offered 8 voices of distinctly analog-sounding DSP-based oscillators. Roland had modelled all sorts of analog functions like oscillator sync, ring modulation and cross modulation. It had a modelled a 2 and 4-pole filter; it had a ribbon controller, onboard effects and phrase sequencing.

Along with the regular waveforms, Roland introduced the stunning Super Saw, which gave the impression of a whole bunch of detuned sawtooth waveforms beating against each other. It was a stand-out feature and demonstrated that Virtual Analog could also be innovative. (Note: if you're interested to learn more about the history of this particularly special feature, check out our dedicated article all about iconic Roland Super Saw.)

Yamaha joined the fray in 1997 with the AN1x. It followed the CS1x of the year before, which successfully pretended to be a VA synth but actually used a combination sampling and synthesis engine. With the AN1x, Yamaha did it properly. It has 10 voices, a huge effects section, and a modular-style modulation engine. It had a bank of 8 knobs that could be directed to all the important things and two scenes where you could swap between modulation settings. Interestingly, Yamaha called it a Physical Modeling synth...which, in a sense, essentially is what Virtual Analog is. These days we tend to distinguish between the two by equating physical modeling to the emulation of acoustic instruments and materials, and VA to modeling the behavior of physical circuits.

[Above: the Access Virus—still one of the greatest VA synthesizers of all time.]

All of these early examples approached VA from a distinctly digital viewpoint. It took a German company called Access Music to really inject the analog intention back into VA synths. In 1997, they released the Virus—and it was a beautiful piece of work. Designed as a desktop unit, it was, for all intents and purposes, an analog synthesizer; it's just that its insides were DSP-based rather than component-based. The layout and controls followed the classic designs from Moog and Sequential Circuits, but with the added variations that DSP could bring. It was simple, aggressive, with phenomenal filters and felt like the real deal. Sprinkle on a bank of effects, MIDI, 16-part multitimbrality and you have one heck of a synth.

In Parallel: the Emerging World of Software Synthesizers

When talking about VA synths the role of software synthesizers is definitely worth pondering. While the hardware element of a VA synth is very important, the sound emulation could just as easily be rendered on a computer as it was on digital signal processors. In the 1990s, DSP chips gave the best-focused performance for Virtual Analog modelling. PCs were powerful, but they had a lot of other things to think about, like opening a word processor or running a spreadsheet, and so had many obstacles in the way of realtime sound generation.

However, Propellerhead Software blew this out of the water with the 1996/97 release of Rebirth RB-338. It was a Virtual Analog emulation of a pair of Roland TB-303s wired into a TR-808 and TR-909. Not only was it terrific fun, but it also bypassed all the problems with computers and audio latency by being completely pattern-based. You couldn't play the sounds from a keyboard; you simply programmed patterns and set it running, just like the hardware.

Native Instruments were among the first developers to lean into the computer platform for sound generation. They released Generator in 1996, a modular environment where you could construct a synthesizer from the familiar building blocks of hardware modular. This later became Reaktor.

Around a similar time, Steinberg introduced VST and ASIO technologies that provided computer users with a low-latency way of dealing with audio. When Virtual Instrument support arrived in 1999 the computer became capable of running Virtual Analog and any other sort of software instrument.

The 2000s saw an explosion in software synthesizers, and the birth of the DAW. Software samplers killed off the hardware sampler industry, and studios focused in on the computer as the source of everything. In some ways software and hardware-based Virtual Analog synths became interchangeable. For instance, at the time, I was running a software version of the Access Virus on a TC Electronic Powercore in my computer.

The In-Between Times

Over the next 15 years, the idea of returning to actual analog synthesis was still seen as largely a ridiculous notion. While there was a growing movement of Eurorack modular and people with soldering irons, the mainstream saw no way back from digitally based synthesis. Eurorack even got its own VA module in the shape of the Mutable Instruments Braids, with classic waveforms and Supersaw snuggled in there amongst wavetable, FM, noise and physical modelling.

[Above: an assortment of later VA instruments—the Yamaha AN1x, Alesis Ion, Korg MS-2000, Oberheim OB-12.]

We saw some fantastic VA synths emerge during this time period as well. Synths like the Oberheim OB-12, the Korg MS2000 and MicroKORG, Alesis ION, Studiologic Sledge and Novation SuperNova. Roland had the Gaia and V-Synth and Arturia even tried to pull their software synths into hardware with the Origin. But as DSP processing got faster and more roomy, the bigger workstation synths pulled in every sort of synthesis, VA included, and so often, it became part of a larger, more entwined source of sound.

VA Persistence

In these enlightened times, the battle lines between analog and digital technologies have blurred and softened. The merits of a synthesizer are much more based on how it sounds and feels to interact with rather than the scrutiny of the underlying technology. Advances in miniaturization and mass production means that actual analog is back in a big way and, in many cases, can compete on price with their digital counterparts. So now all options are open to us. A synth manufacturer can choose to use analog or virtual analog, wavetable or FM, or a big hot mass of interconnected hybrids.

The UDO Audio Super 6 is a good example. It forms its oscillations in the digital environment of FPGA technology, but then runs through an analog signal chain to an analog filter before emerging via digital effects and digital biaural placement. In Waldorf synths like the Quantum blend VA with granular, resonator, FM and wavetable synthesis, and we find similar things in the workstation synths from the big brands. (For more information, check out our full article on hybrid synthesizers.)

Roland has never returned to analog synthesis, choosing instead to push the envelope of Virtual Analog realism. At the height of the analog nostalgia we’ve experienced over the last few years, Roland produced Virtual Analog versions of their most loved classic synthesizers with the Boutique range. Their ACB Analog Circuit Behaviour modelling technology has been extraordinary in capturing the nuance and subtlety of their old synths. They then flipped them into software and back out into “PlugOuts” for the System 8 and System 1 synthesizers. Maybe it's the versatility of that that's attractive and the ability to sell the same synth into different places. Roland has evolved the idea into the ZenCORE technology found in the Jupiter-X and their computer-based software synth, arguably becoming more and more authentic. Their latest offering, the new GAIA 2, combines virtual analog and wavetable techniques into an eminently playable design.

Software has evolved immeasurably and employed all your computer cores to recreate almost every synth that's ever been made. Arturia, Cherry Audio, Softube and Gforce Instruments amongst others have done great work to build astonishing emulations of all the classic analog synthesizers to the point where you have to ask whether hardware VA synths are still necessary.

Modal Electronics seems to think so. Their Cobalt8 and Cobalt5S feature a great-sounding Virtual Analog engine with an engaging interface that gives you one knob per function on all the most common parameters. It has a nice way of combining and merging a pair of oscillators, with morphing and folding options and cross-modulation. I think it wins because it takes all the warmest and most familiar synthesizer sounds from our computer and places them in a nicely built hardware interface.

I think we're well past the point at which the quality of sounds from a computer can match those in hardware, and so end up asking different questions. The question now is whether you want to spend time tweaking presets with a mouse and mapping controls on your MIDI keyboard or have those same sounds ready to go in a dedicated piece of hardware. There’s a lot to be said of how it feels to play a dedicated hardware instrument and focusing purely on that interaction and within the restrictions of it. It’s different from sitting in front of a computer, playing a software synth that sits amongst many others, with a generic MIDI controller.

With all options open to us, we're only left with the nagging idea that analog is somehow better (more on that in this article). But better for what and for whom is still a question that VA Synths like to poke us with.