Tatsuya Takahashi, widely known as 'Tats', is a name that resonates loudly among sound synthesis enthusiasts and professionals. Over the last decade, his innovative mindset has been instrumental in resurrecting the popularity of analog synthesis, crafting a unique sonic landscape that blends tradition with novelty. Takahashi was been the creative engine behind some of Korg's most celebrated modern instruments, including the Monotron, the Volca series, and the Monologue and Minilogue synthesizers.

Moreover, Tats's contribution to the culture of electronic music extends beyond his work with Korg. As a former head of innovation of YADASTAR (a brand that initiated the famed Red Bull Music Academy), Tats has lent his talent to ambitious collaborative ventures such as the Granular Convolver project with E-RM, and the audacious A [For 100 Cars] piece with Ryoji Ikeda.

In 2019, Tats stepped into a new role, becoming the CEO of Korg.Berlin. This distinctive division of Korg is renowned for its commitment to research and development, as well as a strong focus on pushing the boundaries of musical innovation. During 2023's Superbooth trade show event, the Korg.Berlin team turned many heads by unveiling their Phase5 acoustic synthesizer, once again highlighting their unique perspective in the realm of sonic invention.

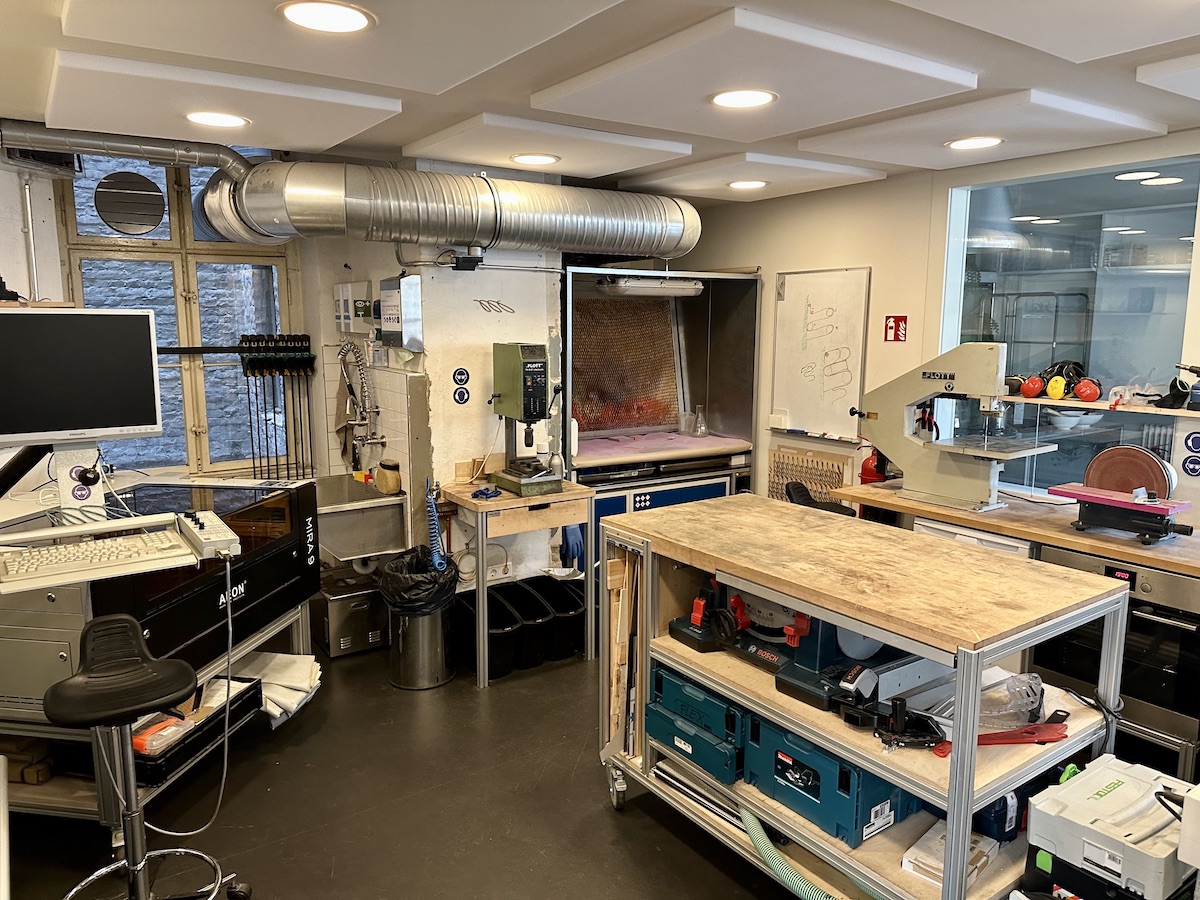

Recently, we had the privilege to visit Tats at Korg.Berlin's headquarters, nestled in the vibrant heart of Berlin's Kreuzberg district. After a tour around the facility, we engaged in an hour-long conversation with Tats covering everything from the experiences he gained building electronic musical instruments and the philosophical outlook shaped by the years of work in the field to topics like sustainability, Korg.Berlin's mission, and their latest invention—acoustic synthesis.

An Interview with Tatsuya Takahashi

Eldar Tagi: Thank you for talking with me, Tats. As someone who's well-known to our audience, let's jump right in. Could you share the defining moment when you realized that creating synthesizers was going to be your career?

Tatsuya Takahashi: Well, there wasn't exactly a single defining moment. I've been interested in sound and electronics from a very young age. The first electronics project I remember doing was building a simple MOSFET amplifier when I was around 11 or 12 years old. This passion for sound continued, and I soon found myself building speakers, something I still enjoy as a side project today.

However, the realization that I should be an instrument designer maybe came quite recently, perhaps after seeing the response of people to the products I had designed. Seeing that people want and appreciate the things I create offered a kind of affirmation or confirmation for me. It triggered the realization that this is the job I should be doing, and I'm quite happy doing it. So, it was more of a gradual journey than a sudden revelation.

ET: Often recognized for reviving analog synthesis, you also emphasize portability and accessibility in your work. Do you have a dedicated philosophy overarching how you approach building musical instruments?

Tats: Absolutely, I do have a guiding philosophy. I need to talk about the values that are present now, and how different they are from when I started. Obviously, I was naturally drawn to music tech, I have always loved circuits, instruments, and synthesizers. So initially, when I started working at Korg, which was my first "real" job after working in restaurants and bars, I was entirely focused on doing my job well.

As you mention, this period coincided with the revival of analog synthesizers, and I like to think that I played a role in that amongst other members of the industry. However, back then, it was more about doing well in my job and fulfilling my passion. The vision or the philosophy wasn't as defined then as it is today.

Now, at 40, I have a different perspective. I look back at the 23 products I worked on while in Tokyo and try to understand what made my job fulfilling. Apart from my affinity for design, art, music, and the very act of creating—of being and doing, I realized that there was also an important external element that stimulated me, and that was the joy that the users derived from my designs.

[Above: Tatsuya Takahashi in the Korg.Berlin studio]

Looking back at it and looking forward, I think this is the defining motivation behind everything we do—to spark joy. As a team, here at Korg.Berlin, we all share this same thinking, and we are constantly asking ourselves "Does it spark more joy or not?" And this question is much more complicated, than it may initially seem because the joy itself, while powerful, can also be easily tainted.

That is why we have set for ourselves these pillars and values, including the question of sustainability. If we're harming the planet while creating amazing beats, then that isn't genuine joy. Conversely, if the sound is not great, it also won't spark joy. So, "sparking joy" is our key metric now in designing musical instruments.

Our creative director, Verena, actually came up with this concept, and it resonated with me. It seemed to encapsulate everything I'd done in the past and align with what we aim to do in the future.

ET: This reminds me of one thing you said in an older interview of yours. You've expressed the musical instruments are capable of fostering transformative experiences. Do you also find there is a similar transformative experience for you when you're building these instruments?

Tats: That's an interesting one. I could just say that joy is transformative, and the design process for me is full of joy. [laughs] I experience an immense amount of joy when I'm deep in the design process, truly in the flow, losing track of time, and just focusing on creating. I like to think that there is an equivalent experience for people who use the instruments.

Although I enjoy using my designs and appreciate other people's designs as well, I don't consider myself a professional musician. I enjoy performing live, but I don't record and produce music extensively. I know how to use a DAW, but it's not something I do frequently. So, I don't claim to have the deep, immersive musical experience that professional musicians might have.

However, I like to believe that the transformative experience I undergo while designing translates into the experience of the user in a music-making context.

ET: Do you use the instruments you've designed when you make music?

Tats: Yes, I do, mainly because I'm very familiar with them. [laughs] It's like reaching for the low-hanging fruit. Plus, I have the advantage of being able to modify my own designs.

In terms of modular synths, while I haven't specifically designed one before, the concept resonates with me. It's like the process of designing an instrument and performing on that instrument become one. Even though I don't design modular synths, the joy I get from the designing process and the use of that design is somewhat akin to the experience of using a modular setup.

With modular synths, you're kind of connected with other people who are designing the modules, and you're participating in a communal process. But I see these as just different levels of abstraction. If we're talking about circuit design, I'm limited by the components that I can buy on sites like Mouser. I don't view this as a constraint though, but more along the lines of standing on the shoulders of giants. You take something that already exists and apply it to a different level of abstraction in the design.

[Above: the Nintendo Game & Watch]

For instance, back in the '80s, Nintendo released the Game & Watch. It was a pocket game device that had a single game on it, predating the Game Boy. The thing that enabled the creation of that machine was the LCD screen which was being manufactured en masse for digital calculators. A smaller brand, Nintendo saw the opportunity in this and re-adapted the same technology to make games, to have fun, and to have joy. I find this approach very appealing.

I really like the fact that the synth business is not nearly as big as smartphones or even most other electronics industries, but we can tap into what big industries are doing and turn that into joyful designs. This is something that I personally take pleasure in doing.

ET: I've observed that collaboration seems to be a central aspect of your work, given your history at Korg and collaborations with figures like Ryoiji Ikeda and E-RM. How does collaboration influence your process?

Tats: I wouldn't describe myself as a particularly good collaborator. I've often found it challenging to share the creative process. That being said, I'm learning to be more collaborative moving forward.

In the past, while I've always understood that a complete product can't be achieved alone, I would attempt to maintain a central role in defining the design, often being quite stubborn about it. What's changing my perspective now is partly my age, and partly my experiences with the new people I've met here.

I've had the great privilege of founding this company, building the facilities and the team. The wonderful people I've discovered have allowed me to view collaboration from a new angle and encourage joint participation in design and ideas. I am madly in love with our team here.

If I can name someone who specifically has been a big enabler in that, it is Samantha, our communication designer who is based in Canada. As a designer herself, Samantha can do anything from product design to the lemonade stand we had at Superbooth. For me, she has been particularly instrumental in promoting a more collaborative way of thinking and working.

As for the projects with Ryoji Ikeda and E-RM, you could say they were collaborative. But we each had our areas of expertise, and the overlaps made it more collaborative. For example, in Ikeda's A [For 100 Cars] project, I was able to apply my skills as an electronics engineer. In other collaborations, such as the Monologue with Aphex, my role was more about UI and industrial design. However we did have a lot of fun, and that was quite collaborative. Well, maybe I am a good collaborator after all…[laughs]...but, anyway I think there's room to make my approach to collaboration more fluid in the future.

ET: I remember from one of the earlier interviews with you that clarity was an important element in your process. Does having these clearly defined roles in collaboration help?

Tats: Actually, I feel a bit differently about it now. While clarity may be necessary for certain projects, our approach with the team here is more transdisciplinary. For instance, I'm an electronics engineer, but I have also designed that orange entrance gate. It may seem that working with transistors when creating a filter and specifying the color for a steel door are very distant things, but it is all design.

If you look at the MS-20, there were very few people involved in that project. The people responsible for the specs, the electrical design, the mechanical design, and the manual were probably the same two or three people. They just operated using general design principles.

[Above: Images of a vintage Korg MS-20, from the Perfect Circuit archives.]

Such an approach brings a certain consistency and purity to the product. Of course, if you are working on a complex product like a workstation keyboard, you need a large team to cover all the layers. However, I romanticize this early era of hardware design where everything was unified. If you look at an old Siemens mic pre, everything from the latch that takes it out of the rack to a three-dimensional puzzle of transformers and vacuum tubes to electrical, mechanical industrial design—all these considerations combined together. It is the same idea here, we try to break the boundaries between different disciplines and just see it as one thing.

ET: So what stirred you toward founding this experimental division of Korg instead of continuing to work on the commercial products in Tokyo?

Tats: I would like to make one thing clear—this operation is commercial too. There is a difference in the approach to how the products are conceived and designed, but the end goal is the same—to reach the market with a product people can buy to create music. We're transitioning from one paradigm to the next in what electronic or semi-electronic instruments could be, not from mass-market products to boutique ones.

Just like the office in Tokyo, we want to deliver our products to as many people as possible, to have a positive impact on the culture, and to deliver more joy. In that sense, nothing has really changed. It is just that we need to do something new here, and that is maybe what seems experimental right now, but these instruments eventually will be rolled out as widely accessible commercial products.

ET: Alright, could you then outline for us what distinguishes Korg.Berlin from all other Korg divisions?

Tats: Yes, absolutely. Korg.Berlin is nearly three years old, and we are a subsidiary of Korg Inc. Our function is to conduct R&D for new musical instruments. We diverge from the main office in that we have a different product planning procedure. We work directly with things, and we try in physical form what ideas might work. By the nature of that, we are a bit more explorative.

Our operation specifically aims to do things differently from the way it is currently done in Tokyo and Asia as a whole, including the manufacturing infrastructure. Having spent a wonderful decade building mainly analog synthesizers, it was important for me personally to do something different here. The team in Tokyo carry on with that work, and they are super good at it. So there is no point in us doing the same thing. That is why we need a different approach, a different technology, a different appeal, and consequently, we need a different branding. That is why we have our own logo, and we identify ourselves as Korg.Berlin. These are some of the things that make us different.

Looking into the future, we feel that some form of this acoustic synthesis that we unveiled at Superbooth this year will be at the core of our forthcoming products, or even multiple product lines.

[Above: Tatsuya Takahashi at work on the Phase5 acoustic synthesizer prototype.]

ET: Let's talk about the Phase5 then. What excited you about the idea of acoustic synthesis to start working on it, and what can acoustic synthesis add to the existing palette of approaches?

Tats: One of the biggest challenges of putting out a musical instrument is, once you start thinking about things like responsible processes, sustainability, and circular business models, you are always faced with a fundamental question of whether we even should release a new product at all. When we are releasing an instrument, we need to make sure that it is something worth putting out. There are so many wonderful products already out there. Do we need new ones? Could we be even good with second-hand ones? That ties to the early notion of "Does it generate more joy?" And the only way we can generate more joy is by putting out something that is truly enabling a different kind of music to be made.

The other question we tried to answer while working on the acoustic synthesizer is what would be the next step for not only electronic but musical instrument design in general. I don't mean this in the sense of looking for a gap in the market, but more about trying to discover something that would be worth putting out.

Actually, to be honest, during the last two years we have been working on acoustic synthesis, and we were not sure whether there was something in there worth being released. But we had a rough idea about acoustic synthesis as something that embraces and harnesses the tonal richness and liveness of real vibrating bodies, whether it be the strings on a guitar or a piano, the tines on a Fender Rhodes, or a drum skin. This involves things like haptics, as well as producing the feeling that one experiences by holding a guitar next to the body or that tingling in your fingers when you are plucking a string. There is a whole level of liveness to acoustic instruments which is completely absent in conventional synthesizers.

So we thought that we need to create something with a dimension of control that electronic instruments offer combined with a very live experience of working with something that is physically vibrating. Something that reacts to the room, reacts to you, and even to noise and interference. You know, like with an electric guitar—it is so noisy, I don't know why people put up with it these days! [laughs] But at the same time, it is a really amazing instrument. So I think that is the leap that we wanted to make, not something that is clinical and controlled, but rather something that feels more live and alive.

So that is the goal behind acoustic synthesis, and in March this year, we finally got to a place where we thought that it can be shown to the world. So we ended up at Superbooth.

[Above: video from Reverb, in which Tatsuya Takahashi talks with Fess Grandiose about the Phase5 acoustic synthesizer]

ET: This reminds me that you've expressed multiple times before a desire to create a synthesizer that would 'beat' the guitar. Is acoustic synthesis a step in that direction?

Tats: Yeah...that is a really long journey, still ongoing. Actually, I play the guitar probably ten times more often than I spend time with a synthesizer. It offers me comfort, joy, and so many other things to me. And with synthesizers—I love them when they are done right, but I hate them when they are not.

So I am asking myself what if a synthesizer could be on that same level where the guitar is? In a way of being there for me all the time. I've always been jealous of a guitar's capacity to be that.

ET: Interesting, being a guitar player myself, I can relate to what you say. With acoustic synthesis, what potential and limitations do you see in this approach?

Tats: We're only in the early days and are still scratching the surface of what acoustic synthesis can do. However, we see a lot of potential in both tonal diversity and a range of applications, depending on how you design it. For example, you can imagine an acoustic-mechanical convolver, which is kind of what a spring reverb is, but in a different way. We can really design physical vibrating bodies that have these distinct acoustic properties.

[Above: a collection of artifacts from material research in acoustic synthesis and instrument design at Korg.Berlin]

The other day our software engineer was playing a guitar through the Phase5, and it sounded so dreamy and beautiful. But it doesn't have to be a guitar. An acoustic synthesizer can manifest itself as a keyboard, a drum machine, and an effect—there is a lot you can do with it. Basically, once you've figured out how to activate acoustic bodies with audio signals, and then found a way to manipulate the response you have the core of an acoustic synthesizer. From there it is possible to expand the technology in all sorts of areas, and all sorts of tonal design.

Regarding limitations, there are some like the size—you can not make such instruments super tiny, but I'm not entirely sure of how small it can be. Other limitations are actually also kind of strengths. Since the instrument is sensitive to the external environment, feedback effects can be quite interesting to explore.

ET: I suppose acoustic synthesis already speaks to an extent of your intuitions toward a certain direction the field may be taking, but I also wanted to ask you a general question about what you would want to see as a future of electronic musical instruments and synthesizers.

Tats: Well, it's a tough question. I imagine a future where synthesizers can be used in a relaxed setting, like on your couch or in your bed on a lazy Sunday morning. I've already spoken a bit about it, but I think there's still room to grow.

The goal is to move synthesizers out of the formalities of a recording studio, and even a bedroom studio, and into casual everyday contexts, much like a guitar where you can just pick it up and play it. Although there are already some products aiming to do this, including those from Korg and other manufacturers, I feel that there is still a lot of work to be done.

As for what we do here, not all of our future products will be focused on this, but some will try to make accessible acoustic synthesis a reality. It would be great if acoustic synthesizers became a part of life, rather than being a part of someone's mancave. There is major work needed to be done in order to realize this.

ET: You've mentioned your focus on sustainability earlier, and I am wondering about does it interplay with this idea of wide accessibility and portability.

Tats: Yeah, we think quite a lot about various approaches. However, designing a truly sustainable product comes with many challenges. We've spent the last three years conducting material research and lifecycle analysis studies on existing and fictional future products. Recognizing how challenging that is, we have set our focus on the carbon footprint of manufacturing and logistics, but other factors, like product longevity, repairability, and end-of-life strategies are equally important.

[Above: a variety of spaces in Korg.Berlin's headquarters]

But the great thing is that the nature of the musical instruments trade is already very circular. If you go on a site like Reverb, you see repaired and refurbished instruments, some of which are maybe 50 or 60 years old. And although the way these instruments are often priced is disgusting, it does demonstrate the circularity of the process.

So it is a complex process involving different moving parts, but we are considering all of these things before we even set up manufacturing. Although I wouldn't claim that I have solved the problem, we will be considering all of these aspects in future production. Longevity is particularly important when it comes to musical instruments because if you are taking care of them they will last for a long time. And yet another factor of circularity that can be easily missed is that we put out the instruments that are worth it. That ties to what I have been talking about earlier, if people don't enjoy the instrument, nobody is going to want to repair it. So joy is a part of making the system circular.

ET: That makes sense. Shifting gears a bit, in recent years we have seen a few prominent trends in the development of electronic musical instruments, things like microtuning, and alternatives to keyboard interfaces for synthesizers. Do any of these trends affect your approach to design?

Tats: Absolutely. The interest in microtuning was particularly sparked by Richard D. James, during the development of Monologue. What is great about acoustic synthesis is that microtuning can easily be implemented here.

In regards to the keyboard as an interface, it is something I'm not entirely sure about. The thing is that the keyboard is established and known, but it can also be hard for some people to master. And alternative keyboards, though ambitious, often end up being even harder to play than traditional ones.

[Above: Some of Korg.Berlin's experimental research materials in keyboard and enclosure design, utilizing recycled plastics and cork.]

Having said that, non-keyboard interfaces are definitely a core part of what we are working on here. We are working on something right now, although I can't talk much about it. But we are not ruling out keyboard instruments. A keyboard-based acoustic synthesizer is a totally valid thing. We're not trying to exclude people who are comfortable with the traditional interface. It is more about the inclusion of other methods that haven't been part of it until now.

ET: What would you consider to be the most rewarding and challenging aspects of your work?

Tats: Hmm…it really depends on what hat I put on. Obviously, the first thing that comes to mind is design. When I get into the flow it is massively rewarding. But there are many other fulfilling moments too, things that we do together as a team. Even something like an all-hands ideation session can be incredibly rewarding to me on a different level. There are really too many to list.

In terms of challenges, the most difficult thing is maintaining purpose. It's about ensuring what we do encourages joy, contributes positively to society, is good for the environment, and gives purpose to every individual in our team. That's probably the most challenging and most important part of my work.

ET: Could you share with our audience an important lesson you've learned on your journey as a synth designer?

Tats: One of the most important lessons, which I've also mentioned in previous interviews, is something I learned early from Mieda, the inventor of many circuits used in Korg. I started working with him about six months or a year into my job in Tokyo.

At that time, I had designed a very early draft of a circuit for what later became the Monotron. To be honest, I didn't have much knowledge about synth circuits, existing designs, or even well-known products. I only knew what an MS-20 was because I was working at Korg, and I kind of had to learn about it.

I was quite naive and not well-versed with important designs, but I still thought I could design a good analog synth. What I put together worked well technically, but when Mieda saw it, he told me, "Your circuits look like measuring instruments. They're technically correct, but to make an instrument, it's okay to make mistakes as long as it sounds good."

That is when I started examining his circuits and I found that the first version of the MS-20 filter, for instance, didn't strictly adhere to the textbook. It had a very "ghetto" way of using a transistor, but it sounded fantastic. It didn't have the best noise spec and had a fairly high sensitivity to parts, which, from the technical perspective, put it somewhere in the middle of right and wrong. But in terms of instrument design, it was perfect.

This lesson was critical for me, probably the most important one.

ET: That's quite an insightful lesson. As a final question, you've just mentioned that you were not particularly synth-inclined before starting to work at Korg, and I am wondering who eventually became the synth designers that you looked up to and learned from?

Tats: My main mentor was Mieda, both philosophically and technically. Also, Horowitz and Hill (authors of The Art of Electronics), and Douglas Self (author of Small Signal Audio Design)...they are not synth designers! [laughs]

I do have a lot of synth designer heroes actually, including people like Bob Moog. The great thing is that probably the biggest learning resource for synthesizers is just old schematics, and I've been privileged to live at a time where you can just search online for something and easily find the right schematic.

That's why we decided to release the schematics for the Monotron. It was a way of giving back to the community and saying, "Thank you, world. Thank you, internet," for providing access to such private design data and the opportunity to learn from them.

ET: Thank you so much for your time today, Tats. It was great talking to you.

Tats: Thank you. It was a pleasure.