Giorgio Sancristoforo is an artist, researcher, musician, film maker, and music software designer from Italy. Over the course of the last 20 years, he has created some of the most esoteric, yet playful independent music softwares, including Gleetchlab, Berna, GleetchDrone, and, as of last week, Fantastic Voyage. All of his software creations possess a strong conceptual core while retaining openness and modularity. His latest effort, Fantastic Voyage, is an ode to the Tascam Portastudio as a flexible modular instrument.

As an artist, Giorgio currently works with materials many of us are trying to escape—various radioactive elements. Sonifying the process in which radioactive decay mutates his virtual DNA, he captures change and transformation in an unprecedented way. Curious about his artistic evolution and processes, we sat down to talk with Giorgio about his past, present, and future work, views on sonic tools, and much more. Enjoy!

Origins

Eldar Tagi: Hi Giorgio. Thank you for taking the time to talk to us. You have quite a diverse background, so let’s start where we always do—can you tell us a little about your background and how you got started making experimental music, sound art, and software?

Giorgio Sancristoforo: Thanks to you! Well, in the early '90s I was really into the second wave of British psychedelia and indie music, such as Spacemen3, Stereolab, Inspiral Carpets, Dukes of Stratosphear, Sundial, and so on...at that time I was a guitarist/organist (I had a Farfisa Compact Deluxe a Vox Corinthian and a Fender guitar), and in 1992 I got my first synth, it was a mint Moog Prodigy.

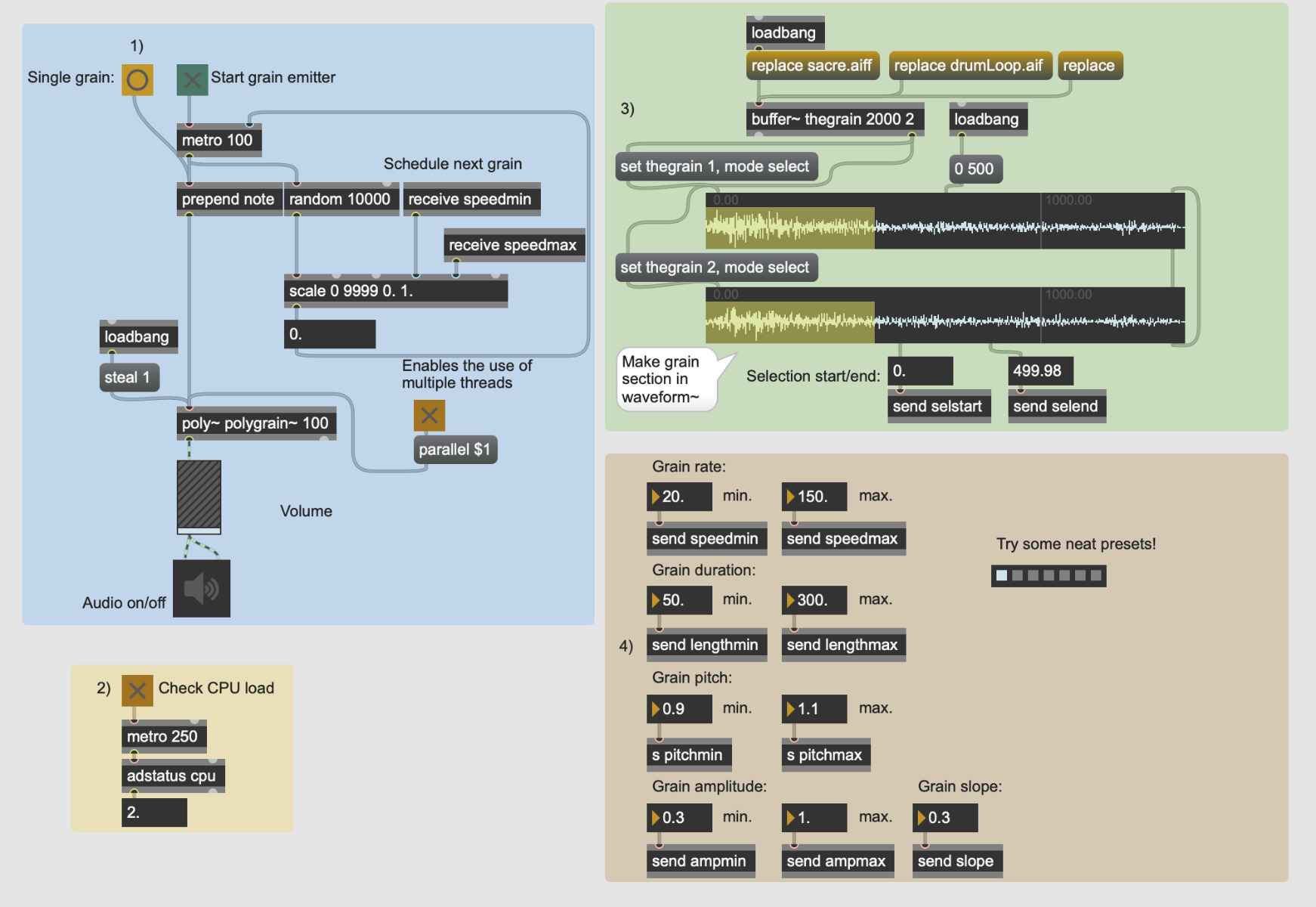

In the last years of that decade, I turned to electronic music, especially Jungle and Ambient. When I was attending rave parties I always preferred chillout-rooms, slow spacey sounds and tripping atmospheres. I really loved The Orb, you know...in 2001, I graduated sound engineer at the local SAE College, and right that time I found the music of Oval with Ovalcommers. It was a huge blast for me. I spent the '90s chasing vintage equipment such as Vox, Moog, Echorec Binson, but after that release I discovered the beauty of digital and glitch. A little later I was studying CSound and Max. I was deeply fascinated by the early electronic music of the 50s, especially the one produced in Milano, at the RAI Studio di Fonologia, and modern laptop music (we called it that way in those days).

Electroacoustics and glitch made me jump in the experimental field. Contemporary computer music (Chowning, Risset, Wishart, Lansky) was also a fundamental step in my musical education. By the mid 2000s, I was already making my first softwares—Gleetchlab 1 was programmed between 2004 and 2005. In 2010 I became a member of AGON, which is one of the historical centers for electroacoustic music here, in Italy, with a large project of soundscape art called Audioscan. From that moment on I started working with composers and performers of contemporary classical music, both as a programmer and performer. John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Iannis Xenakis, and especially Bruno Maderna became my heroes. The models to follow. The step into sound art was consequential.

ET: It occurs to me that you tend to be working on multiple projects simultaneously. How do you maintain your focus switching between all the various projects?

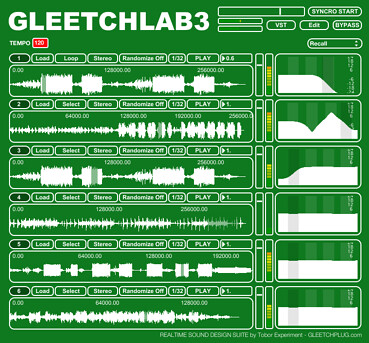

Gleetchlab V3 (2009)

Gleetchlab V3 (2009)

GS: It takes some time for an artist to mature and find his place and voice. For me it was a long process. This is why I had done so many different things, from rock to breakbeats to disco to glitch to contemporary music. So the public often sees in my work a mix of very different things without realizing immediately, that decades passed in between those things. Nowadays my focus is on SciArt. I have no time for side projects, except some softwares, when I can.

I don’t want to make records and I’m not very interested in music performances, my goal is to make artworks. I can say I’m less of a musician now, and more a "traditional" artist. Sound is always paramount in my work, but I also work with photography (well not very traditional), sculptures and botanic projects [laugh]...

ET: A lot of your work revolves around the field of experimental electronic music, but unlike some others, there also seems to be a strong accent on concepts within your project. Is there a unifying concept that ties all your work together, and if so how would you describe it?

GS: I like to create works based on solid concepts. I’m not the kind of guy who makes experimental music just to make nice sounds. Just like conceptual art, my work is based, first of all, on concepts, ideas and sometimes influenced by greek classics. I can’t say that all my past work is unified by a single idea, but this has changed in the last year. With genomics and nuclear (i.e. with "mutation" and consequently πάντα ῥεῖ) I’ve found a concept that I want to hold and evolve. I think I found my theme, once and for all. My genes and radiation are here to stay.

On Max

ET: Cycling 74 Max seems to be a very prominent tool throughout your work. What attracts you so much about it? Can you describe your history with Max?

GS: I started learning MaxMSP in 2000. It was Max 3, if I remember well. I bought my first Mac laptop right for that software, in those days it was for Apple computers only. At first it was difficult to learn—there were no books, no youtube, nothing but a 400 pages manual. But I was tenacious enough to go on. It is better than any synth I had (and I had many). It’s a blank page and you can literally create anything you want with it. It’s not as boring as pure code, it does not constrain you to a timeline, or to bars and pitches.

I owe much to IRCAM, Cycling 74, and David Zicarelli. They created the most powerful music tool I’ve ever had. I work a lot on Pure Data as well, for I use linux and small SBCs in installations. What other musical instruments in the world give you the possibility to craft nuclear physics instruments (I’ve made a gamma spectrometer in Max) or do genomics research, or create new synthesis techniques?

ET: I remember reading in one of your older interviews the awesome trick with using a multichannel .aif audio file with a single sfplay~ object. I suppose the recent addition of MC (multichannel) objects really hit the spot for you? Are you exploring MC in your recent software releases or music?

GS: Indeed, yes. There are many good reasons to use MC objects, beside multichannel audio (I think my last concert in stereo was in the 2000s, lol), for example, Fantastic Voyage has a processor which I called Cosmic Trip, that uses 30 audio channels to create a sort of overlapping grain texture. The signal is converted to stereo before the output, but inside the processor, it runs multichannel. It saves a lot of work and space. It’s a brilliant feature. It’s one of the best new things of Max 8, they really did a great job with mcs.

On Modular Synthesizers

ET: You were using modular synthesizers even before you started working with Max, is that right? What was your first exposure to modular synthesizers, and how did you come to start using them?

GS: Right! My first modular was a Doepfer A100 which I got in late 1995. I was attracted to modulars thanks to the cover of Sterolab’s Mars Audiac Quintet (I think it was an E-mu modular), and Claude Denjean’s Moog! LP which was on my turntable since I was a little kid (stolen from my sister). The modular synth gave me new perspectives in sound design and literally taught me all the basics of analog subtractive synthesis. It was a great teacher and companion.

ET: Now, of course, modular synths have become exceedingly popular. We've seen some of your music that used the Buchla 200e, as well as other works with Eurorack modules. Are there any particular modular manufacturers (or modules) that have been particularly important to your work? Are you still using modular synths regularly?

GS: Around 2010/2012 I had a 200e, a Music Easel, a Synthi A and a Make Noise system. Those were the last hardware synths I had. I’ve used them for live performances for a couple of years, but eventually I went back at Max/MSP, because with hardware I always miss some functions I need: more oscillators, more filters, and the freedom of code. If I want to create an algorithm that, using quaternary mathematics, transforms the genetic code into numbers, I open Max and voilà. Nothing can beat code for me. Nothing.

ET: The videos you posted around 2010 and onward with the Buchla 200e were truly astounding. Although it seems that you work primarily in the realm of software, I wonder if Don’s approach to instrument design influenced your work, and if so how?

GS: I don’t want to sound pretentious and arrogant here, because Don was a giant and he had made history, but to tell the truth...my software ideas influenced the way I used the Buchla, and not the other way around.

One night after a performance I was sitting alone onstage and I simply realised that I was trying to make with the Buchla the same stuff I was already doing on software for years, sadly without the same results. That night I decided to sell the 200e. It was a pain to accept that I really didn’t need those lovely machines. I loved my synths, but after 20 years coding, I know they are useless for me.

ET: Speaking of instrument design, have you ever considered creating a hardware unit? I’m curious what that would be?

GS: Oh well, I would love an Elektron Gleetchlab you know? But (let me fantasize) I would like it expandable easily. Take away a module and upload a new one.

But really I don’t feel like many musicians that need the "touch", the feeling of the hardware. I understand them, but if I miss the "touch" in music, I take my Fender Stratocaster and there I go. It’s not about a tactile experience for me, nor I distrust computers onstage. If I need to work with pots, I take my MIDI Controller and I’m fine. The music tool I need must be vast as my imagination, and again, only code can satisfy this need for me.

But I have a fun project that I will realize sooner or later. I have some cold cathode tubes from the '50s sitting in a lead container. These thyratron tubes are special. They’re filled with radioactive substances to pre-ionize the gas and therefore they use very tiny currents. The ones I have are quite radioactive, they contain Radium 226, and the funniest part of the story is that the brochure of the company didn’t even mention that they were radioactive nor what isotope was inside! Only later, in the mid '60s, they replaced the Radium with Tritium, which is way less dangerous than Radium and has a shorter half life. I’d like to use those cathodes to build a relaxation oscillator with two more oscillators as FM modulators. The "most dangerous generator of the world", hahahaha!

I officially ask Sam Battle (Look Mum No Computer) if he wants to join after the quarantine. He’s amazing and crazy enough to do it. Would you Sam?

GleetchlabX

GleetchlabX

Designing Software Tools

ET: Among the software that you’ve made, I'm particularly fond of Gleetchlab. I remember reading the manual of version 3, which discussed the merits of not being able to save patches, and it was very inspiring. Much like working with acoustic or analog instruments. How was that software born? How have your feelings about patch storage changed as the software (and your practice in general) has grown?

GS: I think that it was a nice idea, and I was severely criticized for that choice. But because the software I sell is just a tiny part of the software I create for my music, I decided to add preset features and let the people choose. You can still work that way if you want. You can start from scratch anytime and I really want to suggest this to the readers here. Any soft synth you have, any software: forget presets. Explore the machine as much as you can as if it had no presets. You will learn ten times more, you will make it truly yours.

ET: The transition from Gleetchlab 4 to GleetchlabX was very fast. What was the reason for this? Also, does the X stand for the final version, or is it an indication of a particular milestone?

GS: I will tell you a fun story. I badly needed scientific equipment. Nuclear research equipment is very expensive, stuff like gamma spectrometers and professional grade radiation meters. I needed a way to fund my research. Software helps me to go further in my work and I really love to do it. Also it was the perfect chance to put Max 8 features in Gleetchlab. But don’t worry, X is not the final version. The X letter was used because I was buying radiation meters for X and gamma rays. :)

Berna

Berna

ET: I also have a question about Berna. When you came up with the idea, was it intended primarily as an educational tool, or do you find something creatively fueling about the workflow of the electronic music studios of the 1950s?

GS: I designed Berna (the composers Berio and Maderna are behind the meaning of the name) as a tribute to the RAI Studios, and primarily as an educational tool. I didn’t expect that so many artists would have used it in a creative way. People like Curtis Roads or Ben Frost. I was amazed. You program a software with your ideas about its functions and goals, but users will always find uses that you didn’t even think of. It’s inevitable. Like in video games: gamers will always find a way to go outside the path that the programmer has created. It’s beautiful and I find it very amusing.

I remember reading a story about when Moog was prototyping the Mini and a Model B was given to Sun Ra. Bob Moog was left speechless after hearing what Sun Ra did with it. He didn’t know it was possible to make those sounds in the way that Herman Pole did. I kind of understand Bob’s surprise. It happens to me very often.

ET: Let’s touch upon GleetchDrone. I really like how intuitive it is. Some aspects of this instrument seem to me to be reminiscent of the Lyra-8 from SOMA Laboratory. Was that instrument an inspiration for it?

GS: Yes of course. They did a great job and I hope they will accept it as a tribute. Sometimes I program software just to challenge myself. If I want some piece of hardware I start to code it and try to make it different to suit my tastes. I added probabilities. I love chance and chaos. I love statistics! Then friends asked for it and there you go...

Fantastic Voyage

Fantastic Voyage

ET: Can you tell us about your new instrument Fantastic Voyage? It was inspired by the Tascam 4-track recorder, is that right?

GS: Yes, the Portastudio was my first recorder in the psychedelic days. No computers, no sequencers, just a tape recorder, guitar, organ, bass, and a few effects. I wanted to create a software to be used as a stomp box but also as a mini studio. I wrote the software using my Stratocaster as a source. It’s the first time that I think of guitar players with my software. But of course you can use it with any source. Try it with contact microphones, electromagnetic sensors, synths, samplers. It’s a tribute to my first days in music making when I was listening to Darkside or Vibrasonic.

It’s a highly psychedelic instrument—you’ve been warned! It also has a glitch tool. You know I love glitches. ;) It’s a very versatile tool, easy to learn and to use, and can create mind blowing textures. It has some Gleetchlab and Berna parts inside, but a bit different.

Making Art Out of Radiation

ET: I would also like to talk to you about your research and installation work. You’ve recently gone into, what many would consider, a dangerous territory—using radioactive materials as a source for your work. What motivated you to take this on?

GS: The first reason behind my love with unstable atoms is a research in random generators. I have a profound love for chaos theory and random numbers. There are a few books which I have had since I was 20 and I keep reading even today because they are a constant source of inspiration, one of them is Les object fractales by Benoit Mandelbrot.

Computers can’t really generate true random numbers, they use a formula to give you a very long string of pseudo random numbers. To get real stochastic events you must rely on hardware of some sort. For example you could use a temperature sensor. But that is not very useful for short scales of time. Once I discovered that I could use my Altair 8800 to get a real string of random numbers. When you turn on this computer you have no operating system, nothing is therefore loaded in the RAM. What’s inside the RAM when you turn it on is a total mystery. So one day I wrote a RAM dumper in assembly code and it worked pretty well.

But there are random numbers and [there are] random numbers. Randomness in nature is seldom uniform like a white noise. Patterns are everywhere in nature (do you remember π the movie?). So I arrived at radioactivity. The decay of an unstable isotope is totally random and this makes radioactivity a very interesting trigger of random events. But even more interesting is the fact that not all radioactivity is the same. Every isotope decays emitting a certain form of radiation. Depending on the isotope we see alpha particles (helium nuclei), and/or beta particles (electrons), and almost always there are gamma rays (photons). Now these gamma decays have specific energy patterns for every isotope. Therefore scientists by measuring the gamma spectrum of a radioactive source can tell what isotope(s) is involved in the process.

So I’ve got a scintillator (a Sodium Iodide crystal sensible to radioactivity coupled to a photomultiplier circuit that transduce photon events into electrical signals) and written a software in MaxMSP to create a MCA (Multi Channel Analyser) to read gamma decay spectrums. The software is basically an unusual form of FFT (for the audio folks) that stores into registers the amplitudes of every bin over a certain amount of time. What do I get then with this data? With this system I’m able to translate photon energies into audio frequencies so the software creates a specific timbre for every different isotope, using 512 simple cosine signals.

ET: Obviously radioactive elements are not accessible to just anyone. What did you have to do to get access to them? How difficult was the overall process?

GS: I use sealed certified sources which do not require a license, they are "exempt quantities". Usually these sources are used for instrument calibration, gamma spectroscopy and physics classes. Of course these objects must be handled and stored with care but virtually these materials can’t pose any risk to my health. Their activity is low and I know how to handle them. I’ve taken several certificates to understand radiation consequences, categorization and detection of radioactive materials, plus a 3 month course of study of MITx in nuclear energy, and the whole year of residency at the Joint Research Centre.

In other words, don’t mess around with nuclear material without knowing what you’re doing, but I can tell you, we are surrounded by radioactive things. Even us, we are naturally radioactive. The funniest news for Star Trek fans: guys we emit antimatter…K40, potassium, sometimes decays with a positron, and we have a good deal of potassium in all our bodies.

The Tannhäuser Gate Installation

ET: The Tannhäuser Gate installation sounds insane. Can you tell us about it?

GS: The Tannhäuser Gate is a sculpture which I’ve realized during my residency at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (the EU Science Hub) for the Resonances III Datami festival. For this work I’ve collaborated with the scientists of the JRC Nuclear Security Unit (Dr. Paolo Peerani), the JRC Biochemistry and Genomics Unit (Dr. Valentina Paracchini), the JRC Knowledge for Health & Consumer Safety Unit (Dr. Mauro Petrillo) and the exhibition designer Cristina Fiordimela. The festival is curated by Freddy Paul Grunert.

Basically there are two huge metal pillars. Inside each pillar, there is a computer which contains my genetic code. My DNA is converted to sound using quaternary mathematics (an algorithm which I’ve called Phonosomic Code) and the DNA is also displayed on LED screens. At the bottom of each pillar, there is a metal container which hosts a source of Strontium 90 radioactive source. Sr90 is a beta emitter, so there are no gamma rays and the 50mm thick container shields all the radiation. When people walk through this gate, a sensor detects their passage and a metal screen rises so that radiation hits a geiger counter connected to the computer. After some time this radiation will mutate my DNA according to probabilities of mutation of the different nucleobases. This will mutate the sound as well.

The Tannhäuser Gate is about transformation and mutation. About life, as transformation is the essence of life itself. This installation has nothing to do with politics or energy, nor with radiation in the Chernobyl sense...for me radiation is simply a fact of the universe (a very common and essential one), in a way it’s natura naturans. Mutation happens in my DNA, transmutation happens in the Sr90 element, and lastly artwork transforms the spectator with the experience of the art (or so I hope). It’s science, but also metaphysics, it’s philosophy and esoterism. The Gate holds many mysteries.

ET: Will this installation be shown anywhere else?

GS: The installation premiered at the JRC-Ispra in Italy in October and then was exhibited at Bozar in Brussels in December 2019 and January 2020. It will tour in other festivals and museums but I will not anticipate for now as the COVID19 is still a huge issue and we have to deal with that before returning to an exhibition schedule. I will keep you posted for sure!

On Making Electronic Music Documentaries

ET: You’ve also done a few documentary films on electronic music, right? Are these films accessible anywhere?

GS: Yes I’ve filmed 11 short documentaries for MTV Italy back in 2006/7. They were also published by Isbnedizioni, but the publisher went bankrupt years ago. Some episodes can still be found on Youtube, thanks to the love of people. They were - not so serious - funny short films on things and people which I admire, from Pansonic to JOMOX’s Jurgen Michaelis, from the RAI studio to Stockhausen.

ET: Is it true that you were the last person to do an interview with Karlheinz Stockhausen? How was that experience for you?

GS: I think that the very last interview was done in Rome for the premiere of Cosmic Pulses, one or two months after my interview. How was the experience? Overwhelming. It was like interviewing Bach or Einstein. I have a profound admiration for Stockhausen. He spoke no stop for two hours. I didn’t say a word. I had no worthy words to say… I just listened in silence, forcing myself to look normal and not in total ecstasy.

ET: Thank you for your time. Do you have any other projects of interest coming up in the near future?

GS: Yes indeed. My work on my DNA has just begun. I’ve refined my instruments and learned to use genomics research software. I have a huge work to do, our DNA is a book of 3.5 billion letters! Right now I’m exploring my mutations. The real ones.

Also I’m producing autoradiographs and gammagraphs with radioactive elements and...well, I’m working on two sculptures (one with muons one with antimatter) and a project with flowers...but it’s a secret for now. I can’t tell more. Thank you so much!