Karl Ekdahl, also known as Knas, is a Swedish-born, US-based artist and electronic musical instrument luthier. He designed the widely-loved esoteric analog desktop effect—the expressive spring reverb, Ekdahl Moisturizer. This year at Superbooth, Karl introduced a wild-looking electro-acoustic instrument called FAR. These instruments are based on the principle of extracting different harmonics from a vibrating string by precisely controlling the speed and pressure of a bowing wheel. Naturally, we were eager to learn more about this development.

In our interview, Karl provides a unique look into the world of Knas, exploring its history, ethos, and philosophy. He discusses his approach to instrument design, the concept and technology behind FAR, and other instruments created by Knas. Additionally, he highlights the important role of Baltimore's artistic community in his work, continuously emphasizing along the way that Knas is and has always meant to be more than just a gear company.

An Interview with Karl Ekdahl

Eldar Tagi: Hi Karl, thank you for joining us. Let's start with your journey. Can you share how you began designing electronic musical instruments? Who and/or what were your biggest inspirations?

Karl Ekhdal / Knas: I grew up in Sweden, largely with electronic music in the ways of the Swedish “synth” sub-culture, listening to anything from Depeche Mode to Skinny Puppy to early pre-goa psy trance. I was very encouraged by my parents to play and write music myself. The issue was that I obviously needed synthesizers, and those things were way too expensive.

My dad got me into electronics at an early age, and thus building my own stuff came quite naturally. My first electronic music project was making a “Covox speech thing” when I was around 11 or so, which made my IBM PS/1 able to output digital sound in glorious 11Khz 8-bit mono using a 4-channel “tracker” called Digi Studio.

From there, it kinda snowballed. I read a bunch of stuff on FidoNet and later joined the synth-DIY mailing list on the internet. This mailing list is hands down the entire reason I could get building for real. It was packed with extremely knowledgeable but also humble people who were stoked to share their knowledge and didn’t discourage you if you asked dumb beginner questions. I built a bunch of pedals and modular stuff, always from scratch because I couldn’t afford kits, and it didn’t seem as fun, to be honest. But having to do this probably also helped me understand things better.

ET: Your website states that Knas is "an art project, a political vehicle, and a company, in that order." How do you integrate and balance these distinct identities in your work?

KE: Actually, I didn’t really want to start a company. I just wanted to build fun things and experiment with sound, but my friend Martin Schmidt (one half of the Matmos duo) convinced me.

One of the reasons I didn’t want to make a company is because I have a huge issue with contemporary capitalism. Having spent a long time reading political and social science studies and literature, it seems that almost all science points toward the hunt for profit being one of the largest problems haunting our world. This egocentric drive creates divisions and a hostile environment that is the cause of most conflicts. It’s systemically used to denigrate, humiliate, and exploit people, and I don’t want to be part of that. I should note here that I’m not just talking about state or party politics, but also a “psychological capitalism”—the general “everyone for themselves” type attitude. I live my life through a kind of “political moral philosophy” where I see everything down to how you treat people as political.

I did, however, decide that since I pragmatically have to still exist in this world, perhaps I could run an anti-capitalist company that is not driven by a profit motive but rather as a vehicle for being able to more deeply explore sound through building experimental music machines. Making my living this way, I could make sure to at least not directly be hurting or exploiting people in the process, though who knows what happens down the line. I also realized that if I could expand upon this and have more people involved, we could together have an alternative way of making an income that lets us escape from the stereotypically authoritarian workplace.

[Above: the delightful chaos of Karl Ekdahl's shop/workspace.]

The key here is that I love sound. I have never made anything that I thought, “Oh, this will sell"—rather, I just do what I am interested in. I get obsessively interested in certain ideas or concepts from an artistic point of view, and then I pursue them. But existing in a vacuum is really boring. I want to share these ideas and concepts so that others can use them too and expand upon them. Unfortunately, I also have to pay rent, so selling my things makes sense from that point of view. But in the end, it doesn’t really matter whether my things are saleable or not because this is what I am going to do regardless of whether I make money or not on it, and I’m still going to have a ton of fun. Even if I was forced into some horrid corporate job, I would still have to make things in order to satisfy my brain.

I think that in order to make a truly fun instrument, you have to be passionate about it. I don’t think it’s really possible to do it from a pure profit motive and actually make something that at least I think is interesting. So in the end, my instruments are my main art form. To others, it may just be gear, but to me, they represent infinitely more.

ET: Baltimore is known for its vibrant and cutting-edge artistic and music scene, and Knas is integrated into it. How would you describe the Baltimore artistic scene to someone unfamiliar with it? What makes it unique for you?

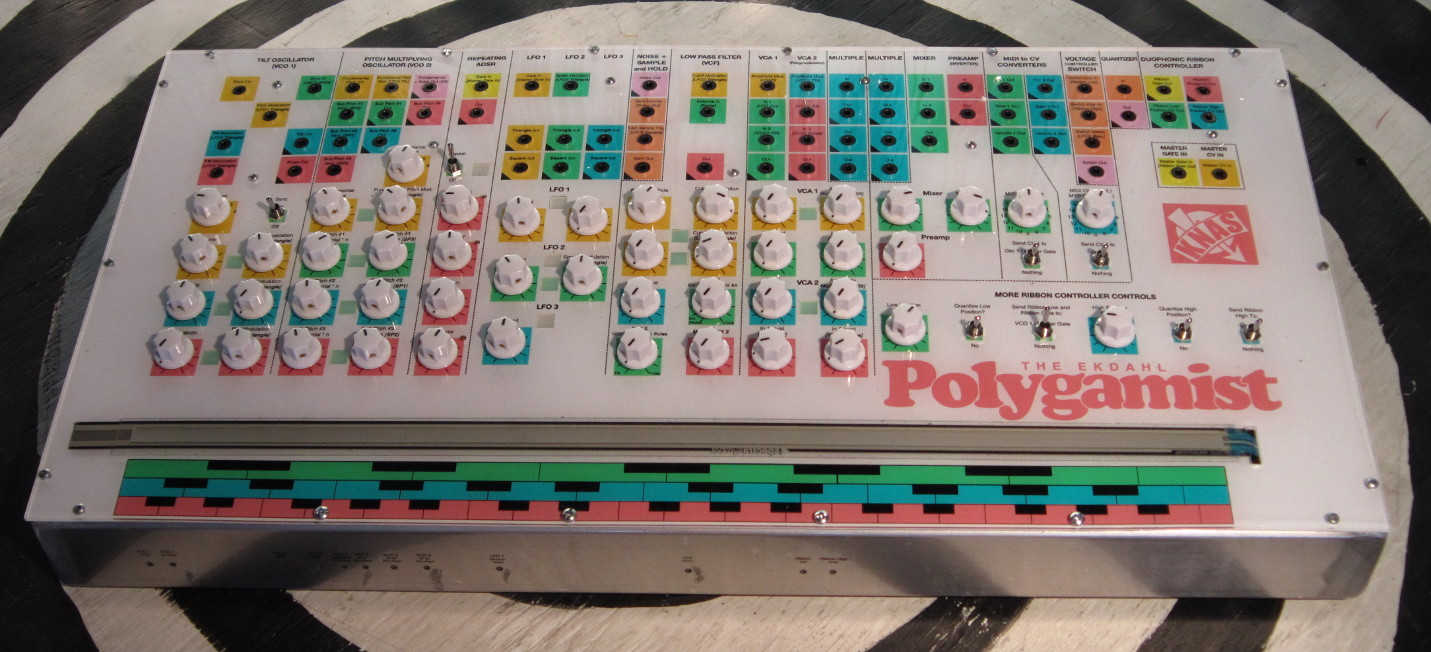

Knas / Ekdahl Polygamist (top); FAR prototype (middle); and a trust ARP Axxe (bottom)

Knas / Ekdahl Polygamist (top); FAR prototype (middle); and a trust ARP Axxe (bottom)

KE: So, in the early 2010s, Baltimore’s music and art scene was an explosion of things happening. It’s not a huge city, but for a few years, there were maybe four or five shows a week I wanted to go to, and at least two I felt like I had to go to. At that time, there was a good amount of warehouse spaces where people lived and did art and music. Many of these places threw shows, and that’s where you went. In fact, I would say that commercial venues had a very small part in creating the scene; it was largely a DIY venture—there were some commercial places involved on the sidelines though, and they were very supportive.

Something that amazed me, in the beginning, was seeing a bill with, say, a punk band, a noise act, some guys playing funk, and perhaps a performance act with someone shaving their legs in a kiddie pool while another person was reciting poems would not be uncommon. I think a huge part of the success of the scene at the time was the lack of ego. New constellations of people doing things together simply because they liked what each other did happened all the time. There were several “bands” that only existed for one or two shows, and that was as it was supposed to be—if you didn’t see that one show, you missed out because it would never happen again. It was an extremely supportive community, and the music spanned a very wide range and was often combined with performance art of various kinds. I feel extremely lucky that I got to experience this for several years.

After a while, the warehouses started disappearing, either by being sold, rent skyrocketing, etc. Baltimore City started cracking down a bit after the Ghost Ship warehouse fire since what we were all doing was technically not legal. Then cancel culture and the pandemic killed off the rest.

The scene in Baltimore was largely dead for a few years, in my opinion. It has picked up a lot in the last couple of years though, but it’s nothing like it used to be. The thing is that it also shouldn’t be anything like it used to be—renewal is key, death and rebirth. Also, I’m like that weird older guy now who doesn’t really know what is going on, probably largely because I myself don’t throw shows anymore, so it’s likely there’s a ton of crap going on that I simply don’t know about.

ET: Your design approach explicitly highlights the roles of faults, imperfections, and chaotic behavior intrinsic to real-world systems. Can you elaborate on your relationship with the concept of imperfection in the design of musical instruments and creative practice in general?

KE: In my view, most interesting art and music is often the result of something unexpected, like you poke around with something, and suddenly something happens that you didn’t anticipate. This is often very inspiring and can make you go places you didn’t even know existed.

To me, my instruments are just vehicles for art. They are supposed to be both tools and sources of inspiration. The idea of something being “perfect” in terms of behavior, frequency response, etc., has essentially nothing to do with making interesting art. I definitely want my machines to be somewhat predictable, and not “unusably” noisy (unless the user chooses to make it so), but what “sounds good” is obviously entirely subjective.

Therefore, I often leave little behaviors in my machines that aren’t the norm, things people can explore and exploit, hopefully in order to make something new.

The entire concept of the Ekdahl Polygamist was to make a machine that could swing from classic analog lushness to sounding like a broken circuit-bent toy. That thing has some behaviors that certainly fall outside of what you normally encounter.

ET: The Moisturizer is perhaps your most well-known invention to this day. What inspired the idea to create it?

KE: So, the story essentially is that the Moisturizer was originally not my idea but my friend Jason Willett’s. He wanted to have an exposed spring reverb that he could play with his fingers. At the time, I was running a music gear repair shop at the back of his record store, and another friend, Martin Schmidt [of Matmos], was working as the record store's “volunteer janitor.” Once Martin saw the initial instrument I built for Jason, he convinced me to develop the concept. I added a multi-mode filter, and after that, Martin thought we should add an LFO as well. So it was a collaborative effort. To this day, I don’t think we have decided who actually came up with the name The Ekdahl Moisturizer.

ET: What, in your experience, have been the most surprising or unexpected ways musicians have engaged with the Moisturizer in their work?

KE: I think honestly the most surprising thing is that it is being used by so many different types of people, situations, and creative endeavors. Seemingly, it attracts anything from people who just want a nice spring reverb for their guitar, to noise dudes banging on the springs, to modular guys, to studios using it as an outboard effect for recordings.

[Above: a trio of Ekdahl FAR, as seen at Superbooth 2024.]

ET: At Superbooth this year, you presented your newest development—FAR. Can you explain what FAR is and how it works?

KE: So, the Ekdahl FAR is essentially an electro-acoustic string instrument whose main way of creating sound is by physically bowing the string with a little felt wheel. By knowing the fundamental tuning of the string and very precisely controlling the speed of the wheel, the instrument resonates specific harmonics in the string. It does this so cleanly that you can get something like five to twelve individual notes per octave over roughly 2.5 octaves.

The bowing wheel sits on a variable pivot, and by pressing the wheel more or less hard into the string, one can alter both volume and harmonic content. Depending on the dampening/muting of the string, you will get more or less of the fundamental note in the mix. The felt wheels are replaceable and come in several different configurations and materials. The choice of wheel, in conjunction with the type and thickness of the string, will drastically alter the type of sound you get. The instrument also has a variable-force hammer for striking the string and a variable mute that can be set to anything from just slightly inhibiting the fundamental, to doing pinch harmonics, to fully muting the string.

ET: Why did you choose the name FAR for this instrument?

KE: My father was hugely into electro-acoustic music. He was part of that whole scene in the '60s and forward. He would have absolutely loved this instrument, so it is dedicated to him—“far” means “father” in Swedish.

I find that the name plays well when put into an English context as FAR simply sounds good as an acronym for something, but I also hope that this instrument is going further into the realm of sound creation.

ET: You mentioned that FAR, by design, is open-ended both in terms of performative approaches and sonic transformations. What ways of interacting with it and modifying its sound have you discovered and found to be the most interesting so far?

KE: The Ekdahl FAR is fully MIDI, USB-MIDI, and CV controllable, and both CV and MIDI controls can be remapped to do just about anything. This was kinda required since the instrument can be played in ways that go outside of the standard MIDI paradigm of note on/note off. I found, for instance, that it’s imperative to be able to sequence both the bowing wheel, hammer, and mute separately at times.

[Above: Ekdahl FAR controlled via CV from ARP Axxe]

I expect some people will do tonal things with the instrument using a keyboard, while others will dive into ambient landscapes improvising on the control box. Modular people will probably find some super weird ways of playing this thing that I haven’t even thought of.

Personally, one of my favorite ways of playing it is by just hooking it up via CV to my ARP Axxe and using it as an acoustic slave oscillator while doing drone-improv using the control box on another guy.

While the instrument in itself doesn’t require the use of a computer, I am developing a configuration utility where the user can do massive alterations to the instrument but also just do regular things like change the fundamental frequency when, for instance, changing to a different type of string. In terms of strings, any metal string will work. So far I’ve tried acoustic guitar, electric bass, electric guitar, mandolin, piano, cello, viola, etc., and they all sound very different.

[Above: detail of the FAR control panels at Superbooth 2024.]

ET: You also indicated that in the future, the instrument will be hackable, allowing for user-defined modifications. What aspects of the instrument will be open to customization? Also, how do you imagine this will translate into the sonic capabilities of the instrument?

KE: I'm going to make both the firmware and configuration software open source. My hope is that with help from the community, we can make this thing the best instrument it can be. The firmware is made to be internally modular so that one could also change it to suit other hardware configurations. It is already prepared for doing multi-string versions of the instrument.

The hardware is sectioned into sort of “modules” and is positioned along a generic aluminum extrusion. The idea here is that things like the pickup, hammer, mute, etc., could either be replaced or upgraded with future things either developed by me or by others. It is also completely possible to just get your own extrusion and make, say, a 15-foot version by putting the modules on that and simply adding some cable extensions—why not? The way I see it, this is not just an instrument but rather it’s an expandable base for what could hopefully become an entire ecosystem of electro-acoustic experimentation.

ET: What sort of challenges are you dealing with in the development of an instrument with such an extendable design, and how do you tend to resolve them?

KE: So it turns out that physically resonating specific harmonics in a string is VERY difficult. Very precise measurements of the bow’s rotation are required. The motor's speed changes depending on the pressure with which it is pressed into the bow, but this is also very dynamic and will change sometimes hundreds of times a second since once the string starts resonating, it will “bounce” into the wheel, changing its speed. It would probably have been much easier if doing the classic induction trick (like an ebow), but I specifically wanted to be able to hear the bowing wheel scraping against the string. It makes for a very physical sound.

Another issue is the fact that I’m using a 600MHz processor, three motors, and a solenoid on an instrument that is also supposed to produce very clean sound using an electromagnetic pickup. This is quite a challenge. [laughs]

[Above: Ekdahl FAR controlled via CV from ARP Axxe—with lots of sunlight]

ET: What is your current roadmap to get the FAR out in the world?

KE: My hope is that I will finish it this year, but I’m not gonna stress it. It won’t be released until I’m happy with it. I am considering doing a “beta run” before the actual launch, where I will let a few interested people buy a unit and test it out, knowing that there will definitely be firmware upgrades required and possibly also minor hardware modifications. I’m undecided on how exactly this is going to work because I will have to ask people to pay money for an instrument that isn’t quite finished—but it’s either that or no instrument at all because I don’t have the money to hand things out.

ET: What other projects are you currently working on?

KE: I am not working on anything else at the moment because I don’t have the time, but working with the FAR has given me a ton of new ideas, so I’m actively suppressing them so that I won’t get sidetracked. [laughs]

ET: What do you like to do when you are not working on musical instruments?

KE: Honestly, not enough time. I work 10–14 hours per day, six to seven days a week, and have been for a long time. I go to shows when I hear about anything interesting, but otherwise, it’s all work and no play. [laughs] Though considering my work is a lot of just playing the FAR and dancing around my workshop, it isn’t that bad.