Synth History is a magazine, podcast and website focusing on synthesizers and the musicians who use them. Founded and curated by musician and producer Danz CM, the Recommends Series is a special segment in Synth History's yearly printed magazine.

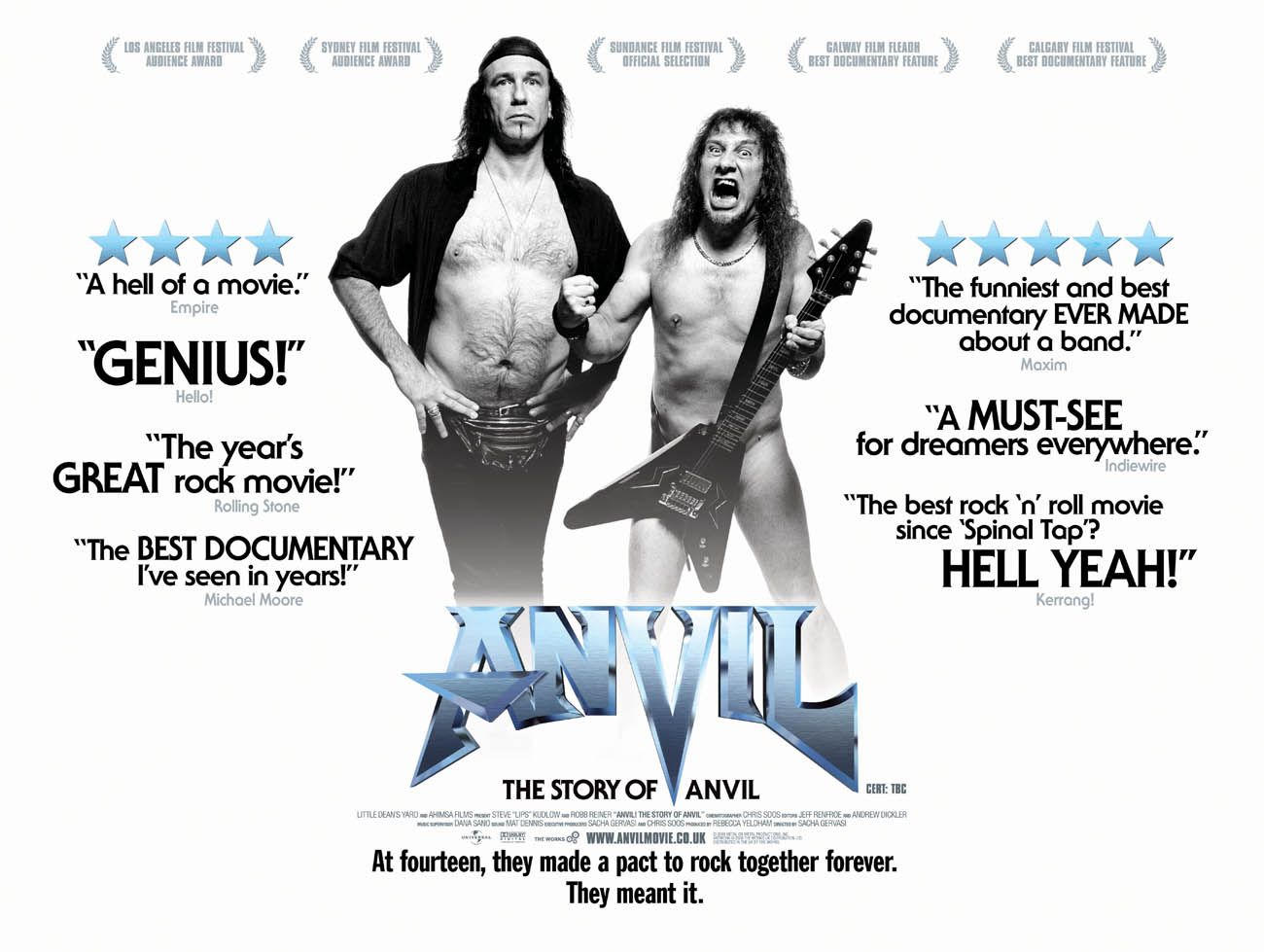

The documentary Anvil! The Story of Anvil is one everyone should watch. I had the chance to see it in theaters a little while back in Los Angeles with an introduction from Steve-O. Yes, that Steve-O!

The film mainly follows Steve "Lips" Kudlow and Robb Reiner of Anvil, a Canadian heavy metal band that gained cult status in the 1980s. The film begins by listing Anvil as one of the headlining acts of Japan's 1984 Super Rock festival. Other headlining acts of the year included Bon Jovi, Scorpions, and Whitesnake—all of whom would go on to sell millions of records. Despite their drive and talent, Anvil weren't able to achieve the same level of success—in the documentary, Lips drives a truck for a catering company, delivering food to schools; and Robb works in construction. The film follows Anvil, now in their 50s, as they continue to pursue their dreams.

If you're a musician, or any person pursuing a career in the arts, this film will resonate with you. I think it will especially resonate with you if you grew up with a humble financial background and without relatives or connections in the entertainment industry. Without a safety net or financial support, aspiring to make it big and shoot for the stars is significantly more difficult. Not only do you have to work harder to earn any recognition, compared with those who have the ability to pay for certain levels of success; you also have to figure out a way to simultaneously live in the interim. The cushiony ability to solely work on music? Yeah, right. You need to figure out a way to pay your mortgage, your electric bills, your phone bills, your insurance bills, your car bills, you need to eat, you need to survive. A safe 9 to 5 might be out of the question, because what about your dream? So you get a part-time job to make ends meet, which might eventually turn into a 9 to 5 anyway because you’re financially stressed.

On top of all that, without a golden ticket or a way in, via a well-connected manager or relative, the chances of you being seen or heard are extremely slim. If you grew up without even knowing anyone at all with any experience in the industry what-so-ever, the cards are stacked against you there, too, because you're left to navigate it yourself and can get taken advantage of easily. Lastly, without the emotional support of a family that understands being a musician is a fathomable career choice to begin with, you might question your own dream. As an example, my parents made me believe that being a musician was a hobby, a phase. They'd say, "That's nice, but what is your plan?" What was my plan? I didn’t have one. But my dream was to make music and to be able to live doing so—far-fetched enough, for an artist who didn’t grow up in the entertainment industry and with a family uninterested in the arts. It wasn't until I started to make any money from music that they respected my dream at all, as a plan in itself.

You might find the majority of people in the world equate "big dreams" with fairytales until they come to fruition, and you might find most people equate being successful with making money. If you’re an artist who has a dream, who is taking that risk, who is shooting for the stars as they say or just yearning to live comfortably doing what you love—sometimes, your only way to get there is by believing in yourself.

Your big moment might come, and it might not. The older you get, the less likely it is to come. So what keeps you going, knowing all of this? Knowing how hard it is now, and how hard it will continue to be—knowing that in reality that big moment might never actually occur? It's simple. What keeps you going is the happiness you get from doing it, the inherent need to make art, and truly knowing with all your heart that it will happen, someday.

And it happened for Anvil. Maybe it was happening all along.

The Story of Anvil is inspiring for anyone with that dream.

Without further ado, an interview I conducted with Lips of Anvil. You might not think of synthesizers when you think of Anvil, but Lips is no stranger to their importance, although he might be wary of drum machines.

An Interview with Lips from Anvil

Synth History: What is Anvil's take on synthesizers?

Lips: We use them. We use them in our recording, particularly on the Metal on Metal and Forged in Fire albums.

Synth History: What do you think about them, any favorites?

Lips: Well, we used a vocoder, which was the earliest version of fake singing. And you could either play it on the keyboard or you could actually sing into it and synthesize your voice, make your voice sound all different ways. And that was extraordinarily useful. We used it on a song called "Mothra" from my recollection, I can't remember what we were using it on in Forged in Fire. It might have been on "Free as the Wind." We had used it for vocal textures, and the Taurus pedals.

Synth History: Nice. Taurus pedals are pretty legendary.

Lips: Yeah, those were used on those albums and they were very important, extraordinarily important. They completely fortified the bottom end. The opening of the song "666," the first thing you hear is the sound of that. [Makes Taurus sounds]

Synth History: Do you have any favorite guitar pedals?

Lips: I'm using a Boss Echo that's, you know, one of those echoes with an EQ, and I use a Tokai Distortion pedal from the early '80s, TDS-1 or whatever. I collect them. And in fact, I just ordered another one on eBay [laughs]. And you can find them for about 100 bucks, there's nothing better. I've never heard a better distortion pedal in my life. So I collect them. And that way, I never have to worry about losing my sound.

Synth History: You always have one in the chamber in case one breaks down.

Lips: Yeah exactly, but the real truth is, I’ve only had three breakdowns in 40 years. So I've got something like 10–15 of those pedals. I had to replace one about a year ago and who knows? We don't know why. I took it to the repair guy and we couldn't fix it. So that was it.

Synth History: What is your take on drum machines?

Lips: As long as you have a real good drummer programming it, that's number one. But number two, [they are] very, very sterile.

Synth History: Not enough of the human human touch?

Lips: As Anvil, I would never even consider it. It’s never gonna happen. Why would I even consider such a thing when I've got a drummer like Robb.

Synth History: What were your favorite bands growing up?

Lips: Deep Purple, Black Sabbath, Captain Beyond…you’re going “What's that?” Montrose. Cactus.

Synth History: How about currently?

Lips: I don't think I've been inspired by anything in years. [laughs]

Synth History: [laughs]

Lips: I'm being honest! I still listen, like most people, I listen to the music I grew up with and stay there. Right? Because what I find, it's a different world today. What people are considering music, I don't even consider it music. I didn't understand why my dad didn't consider what I did music, and if he heard what's around today, he'd be going “oh my god!” You know what I mean? It's like he came from the era of Artie Shaw and Glenn Miller and when he heard Jimi Hendrix he’d go “Shut that fucking noise off!” Now when I hear something like Death Metal, I go “Shut that fucking noise off!” and I'm going “You call that music?” That's the same thing my dad used to say. So I think thats part of what life is and what rock and roll is, always take it to the next level to piss off your parents, right? So if your parents like Chuck Berry, bring home something that will definitely turn his stomach.

[Above: power for Anvil: the Story of Anvil]

Synth History: Are you excited about the re-release of the doc, are you touring or anything?

Lips: Actually, no, no on all accounts. It's hard to get excited about doing it the second time. There's nothing like the first. I'm kind of apprehensive about it more than I am anything else, because I'm trying to figure out what's going to happen. It seems really odd. Off the beaten tracks, so to speak, it's like “what?”

Synth History: One of the things I find magical about Anvil and about watching the film for the first time was how incredibly positive your outlook on life was no matter what hardship you and the band were facing throughout the process. I find it really inspiring and I’m curious, did you have any sense at all what kind of response the doc was going to get as you were filming?

Lips: My predictions were completely spot on. You're gonna find this pretty bizarre, but when Sasha [Gervasi, director of the film] sat me down and told me he was going to make a documentary, before we even filmed anything, I knew what it was, I knew where it was going. I said, “You know how many millions of people are going to be tuned into what we've done?”. I knew my boat was coming in, so to speak, and my prediction was it was going to be seen by at least 20 million people by the end of the day. And they're [Sasha and producers] going, “that would be really nice”. That was my prediction at the beginning of it all. And I don't think I'm going to be far off the mark. And, in fact, it may surpass that by the end of it, by the time I'm gone, let's put it that way.

I think that in the 13 years that it sat on the internet, whether it was Sky TV, or whether it was on YouTube, wherever you might have been able to find that video, or even the DVDs, it definitely made its mark to the point where it's being released again. So, there's going to be another unfolding of more people and actually a new generation. I think that maybe I'm not that far off the mark by thinking that it was going to be seen by 20 million people by the end of the day [laughs].

Synth History: Did your life change after the documentary?

Lips: Oh, of course it did. It’s obvious right? It changed everything. I mean, I think it's pretty well known. We did shows with AC/DC, we haven't stopped touring, we've put out six or seven albums since that point in time. To be honest, there's a lot of sort of negativity in the sense that, “oh, they never made it”. It depends on what you perceive as what “making it” is. To me, the most important thing and what "making it” is, is writing an album and getting it out. One way or another, it doesn't matter how many sold, just getting it out. The most success that you can have is, how many songs did you write? It’s the guy who wrote the most, it’s the guy that released the most records that is the most successful, in my opinion. It doesn't matter about the record sales, whatever! That person, whomever that is, has sat down and written all that music. That's impressive. That's the work. What you get paid is not necessarily equal to what the work was [laughs]. If you were successful in being able to do that work, especially in the music industry, being able to tie down record deals to pay for all that, I don't think anything can be more successful than that. So when people go, “Hey, man, they were unsuccessful”, unsuccessful at what? Making music for 50 years? If you were unsuccessful, you weren't able to get a record deal. You weren't able to ever tour. You weren't seen or exposed to anybody. That's being unsuccessful. I don't know that you could really measure Anvil’s success.

I'm gonna be really honest about this and tell you stuff that you're gonna go “What?!”. We met Roger Glover from Deep Purple, and he was losing his shit. “You are legends. You guys are the real legends.” And we're going, “What? You're the bass player of Deep Purple. What do you mean? What are you calling us? What!?”

As far as Roger Glover was concerned we were more successful than he was [laughs]. I'm laughing because it's, in a certain sense, sort of, I don't know, what's a compliment worth? You know what I'm saying? Sometimes, you could make millions of dollars and never get a compliment. So a compliment is worth a lot.

Synth History: You have obviously had a very prolific career with many albums that have come out, I think you'd be the perfect person to ask, how do you get over writer's block?

Lips: I don't even know what it is [writer's block]. I don't know what that means. Like I honestly, I don't know what that means. I’ve wondered about that for many, many years and I think that it’s just an excuse for being lazy. That's the only thing that I can really surmise. I just don't get it. I can pick up the guitar and create something right now if I want to. It's like breathing, I don’t know how else to explain it. It’s like someone saying “What if your breathing gets blocked?” You’d probably die. That's called being strangled. I don't understand the concept, can you ever stop the little voice in your head? No. Does it ever shut up? No. Well, that's the same thing. When you pick up the guitar, you start playing a riff? What the hell? You can make anything up. You can make anything up, any time you want. There's no rules on it. There is no such thing as “block”. What is that? It's not wanting to pick up your guitar and do it. That's writer's block. You're blocking yourself. There is no block. It's an individual thing. It's how you perceive the world or want to perceive the world. To me, I don't know what it means.

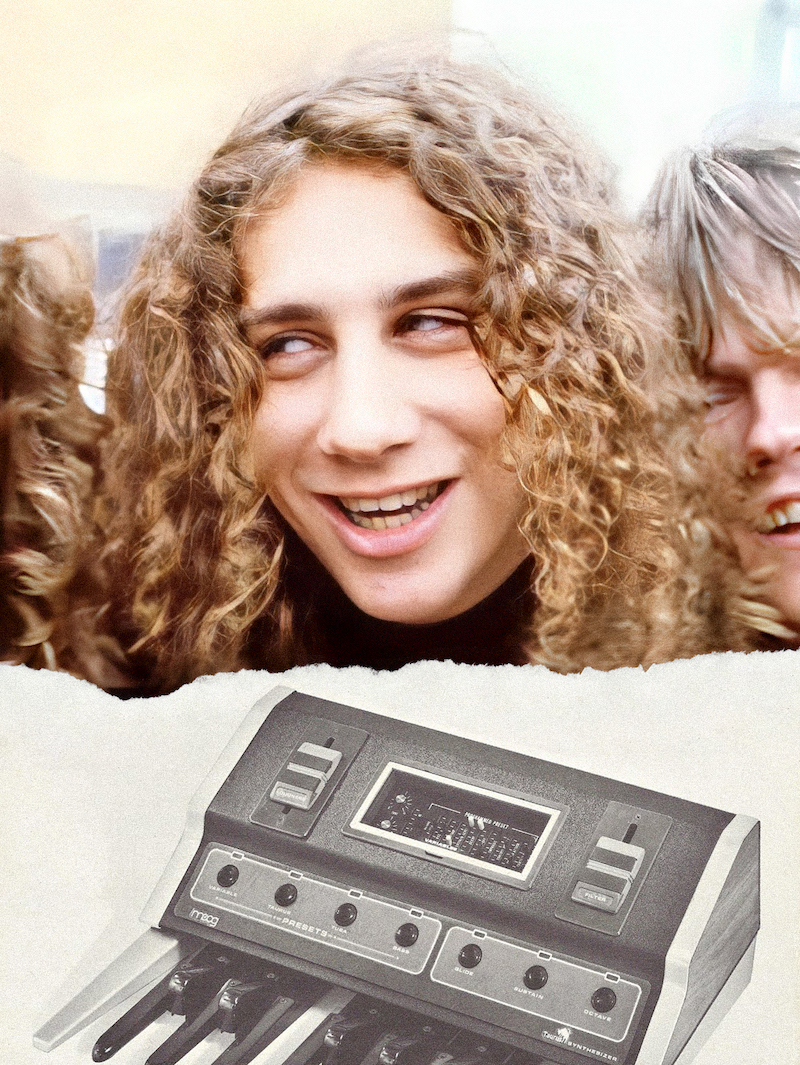

Lips of Anvil with Moog Taurus pedal bass synthesizer

Lips of Anvil with Moog Taurus pedal bass synthesizer

Synth History: If you have one singular piece of advice to give artists of any field, what would it be?

Lips: It’s all about originality and individuality. It's all about that. And without it, you're going nowhere.

You want to become a copy band? Well, that's what you are. You're never going to be famous and you're never going to be known for anything other than somebody else's music. So that doesn't work, you know, being a duplicate of something else. Trying to be like something else is also not going to work because somebody else has done it and they already made it doing it. So how are you going to do that? Because we already got one of them. You know what I mean? You've got to find your own identity. You can think of an endless amount of bands that all sound like Led Zeppelin and they’ve all basically been one hit wonders. It works for the short term, but not for the long term because you never can keep it up and it becomes redundant very quickly. Because you're not the originators. You can get the recognition of “Hey man, these guys sound just like Led Zeppelin” and everybody goes and buys their record to hear that. And then when you put out your next record, everyone knows what you sound like so they don't care. It's not Led Zeppelin.

That's basically what happens. I guess there's a new one that's like Fleet or [Greta] Van Fleet or whatever it is. I can't think of the name. And then Kingdom Come from a number of years ago. There's been others. The Zeppelin-esque copy. It never lasts because you’re not them. You're good for a novelty to go, “Hey this is a new injection of Zeppelin-esque music” but it doesn't go further than that, because they don't believe in you in the same way that they believed in Jimmy and Robert. It's just as simple as that.

So it just comes back to originality, you've got to become something that no one else can be, but you. That's what it's really, really all about, originality and coming up with something that no one else does. Or, at least, coming up with something that no one else does like you.

Originality can come in lots of different ways. For me, it's not just that [singing], it's the things that I do when I'm on stage. Such as my vibrators, such as yelling into the pickups on my guitar. Those are signature things that belong to me. No one can repeat them because I did it. I did it first. And I'm still doing it. They’re signature things that are original. Like, who yells and screams in their pickups? I don't know anyone else who does. And it's interesting because most guitar players don't realize that you can do that. I discovered it. I discovered it at one show in Belgium in the 90s when the PA went off and I had to sing the last verse of Mothra. I had this idea, the PA is off, everybody can still hear the music, but no one can hear the singing, but we still had a second guitar player. So I thought, “Well, why don't I just sing the last verse right in my guitar”. So I sang the last verse right into my guitar, and it worked! So from then on, I started using that as part of the show, I would yell out “Hell Yeah!” and I get the audience to yell back. You have to find things both visually and musically that are unique. That no one else does. Then you’re sailing. The only place they can get it is from you. So guess what, now you're making a living.

Synth History exclusive. Interview conducted by Danz.

Check out Synth History at Perfect Circuit!