In the late 1940s and beyond, electronic aural alchemy was taking place in the audio labs of Raymond Scott. Using self-engineered electronic instruments, he spent decades researching the secrets of synthesis, sequencing, and the collaborative composition of music between humans and machines. While his work did impact some of the most consequential figures in electronic music history, like Bob Moog and Herb Deutsch, in large part, Raymond Scott’s engineering accomplishments existed in a vacuum; their greatness and significance was and has remained largely unknown.

Hungry to learn more about the mysterious musical labyrinth that is Raymond Scott's work, I spoke with his son, film editor, and filmmaker Stan Warnow. I also spoke with music producer and audio restoration expert Brian Kehew, who is leading efforts to restore Raymond Scott’s incredible Electronium, and former Moog Clinician, and Dr. Thomas Rhea. Their insights will help us decode Raymond Scott’s cryptic yet undeniably substantial contributions to the world of electronic music, synthesis, and the artistic collaboration between humans and machines.

Before Raymond, there was Harry

Raymond Scott was born in 1908 as Harry Warnow. He grew up in the predominately Jewish and Irish neighborhood of “East New York,” where his father owned a music shop. There, he met his first music teacher: a player piano, also known as a pianola.

A player piano is an automated piano that plays musical notes recorded onto a metal or paper roll. You’ve probably seen one or two being routinely abused in Western film saloon brawls. Learning through the mechanical precision of a machine would prove to be a fundamental cornerstone of Harry’s musical expectations and pursuits going forward. From the very beginning, technology and music were linked from Harry’s perspective.

Harry enjoyed exploring the large variety of different devices found in the shop. This exposure cultivated a strong passion for audio science and technology; he went as far as building an audio lab in his bedroom when he was still a child.

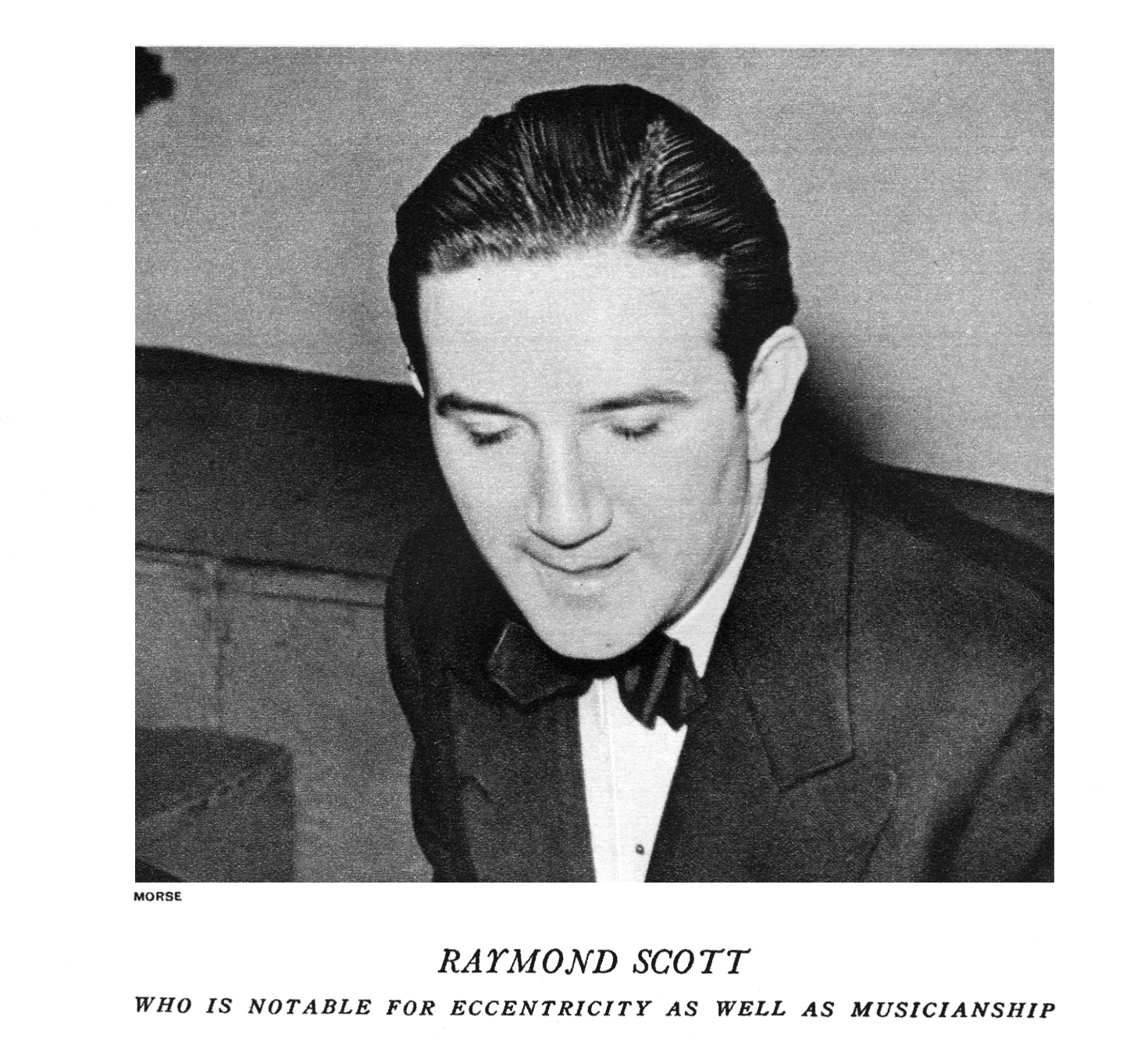

[Above: image from Coronet magazine, August 1940.]

Harry Warnow didn’t have the best people skills. He was shy, something that never changed, even after he became a famous household name (as Raymond Scott). Video of him on national TV being interviewed reveals what looks like a painful social anxiety. But early on, he learned that he could rely his talents to get him through life’s social necessities.

"He was awkward socially, but at parties, he would sit at the piano and play for hours and write songs on the spot… He would write real melodic tunes on the spot," said Stan Warnow—his son.

But Harry didn’t stop there. He would also make recordings on the spot at parties, too—an extraordinary experience in the 1920s and '30s. When courting his future wife, he would covertly record part of a telephone conversation and then play the recording back on the same call. At this point in history, there was a spooky or unsettling factor to hearing a recording of your own voice, perhaps akin to someone pranking you with a hologram today: eerily impressive and barely possible. How would you react to unexpectedly seeing yourself walk through a doorway?

Music Career

After graduating from Brooklyn Technical High School, Harry planned to pursue a career in technology, but his brother, Mark, offered to pay his tuition and buy him a Steinway piano if, instead, he chose to study music. Mark was himself a professional musician and composer and knew Harry’s talent was too great to ignore. Harry took him up on the offer.

In 1931, Harry Warnow (i.e., Raymond Scott) graduated from New York’s Institute of Musical Art, known today as Juilliard. He began working as a pianist in CBS radio’s house orchestra, the same orchestra Mark conducted. It was around this time Harry Warnow became Raymond Scott. He is said to have plucked the name from the phone book because it had a nice rhythm.

Scott went on to have a thoroughly successful career as a composer and bandleader. His acoustic arrangements were just as innovative and eccentric as his future research in electronic music. Scott’s music has a distinct auditory trademark that’s instantly recognizable. He used jazz techniques and conventions in very composed and painfully rehearsed pieces. The result was wildly emotive, as jazz is, but rather than the seeming chaos of the day’s jazz improv, Scott’s music was catchy, descriptive, and memorable. It’s difficult not to get some kind of picture in your head when listening to a Raymond Scott piece.

[Above: Raymond Scott's piece "Powerhouse," featured in Looney Tunes]

Interestingly, Scott’s music was used extensively for Warner Bros. cartoons, to the point that, for many, his music has become synonymous with Looney Tunes. Much later, Scott’s compositions also appeared in the cartoon series Ren & Stimpy.

Extraordinary success in the music business would fuel Scott’s constant exploration of the intersection of music and technology. As his means grew, so did the scope and seriousness of his electronic music experiments.

Raymond Scott's Inventions

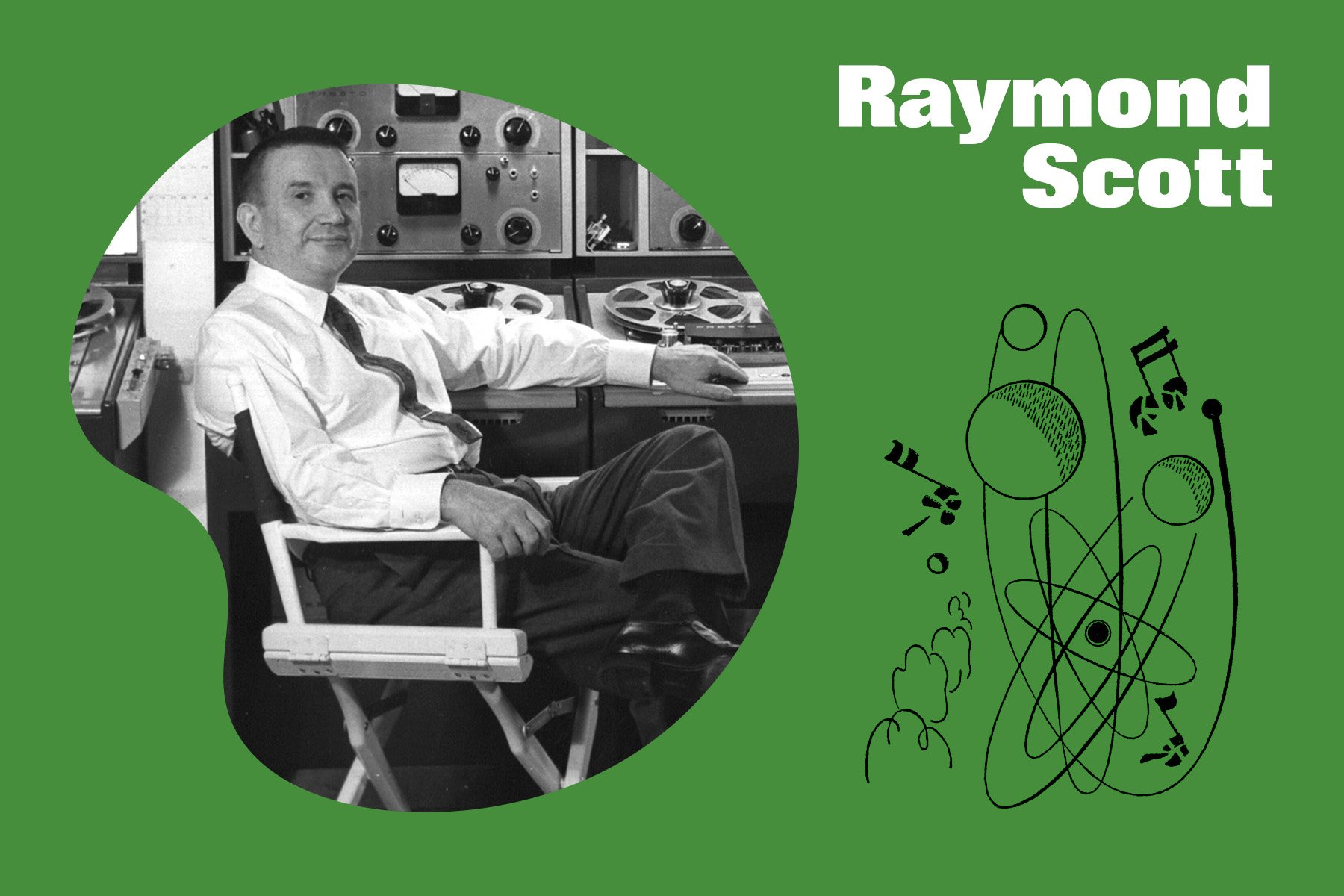

[Raymond Scott in his electronics workshop; North Hills, NY, c. 1959. Image from Raymond Scott: Artifacts from the Archives]

Raymond Scott built several enormous audio laboratories in his lifetime, the most notable in his mansion home in Manhasset, New York. These places are where he channeled his passion for technology into the creation of new electronic instruments and other novel musical devices.

Scott's creative instincts were constantly firing, leading to many more ideas and ambitions than he could possibly build, even given his substantial means. But he did record many of these ideas. A personal favorite is what he called the Fascination series: a collection of ambient music-generating boxes that fill a room with an ever-evolving aural color. I’ll take that over random streaming playlists any day.

Other ideas make you strain to wonder how Scott ever thought them up. Brian Kehew elaborates:

He had an idea for a doorbell that changed its sound every time you pushed the button. And that is an idea, and it is interesting… You can have doorbells nowadays with selectable [tones] three different chimes or something. But, one that changed every time?He wanted to have a sound generator inside of it that was sort of random… How do you know when the doorbell’s going off, then? If it sounds like a scratching noise, if it sounds like a weird hum, cause, you know, it’s randomized, or it sounds like a tiny whisper, and you don’t hear it, or it’s really loud and annoying. So, he didn’t think these things through.

Thankfully, Scott did get around to building some of his most impressive ideas. Many were groundbreaking with history-altering potential.

The Karloff (1946)

The Karloff was Scott’s massive sound effects generator. Its uncanny timbres would prove to be particularly effective for Scott’s musical work with commercials and advertising.

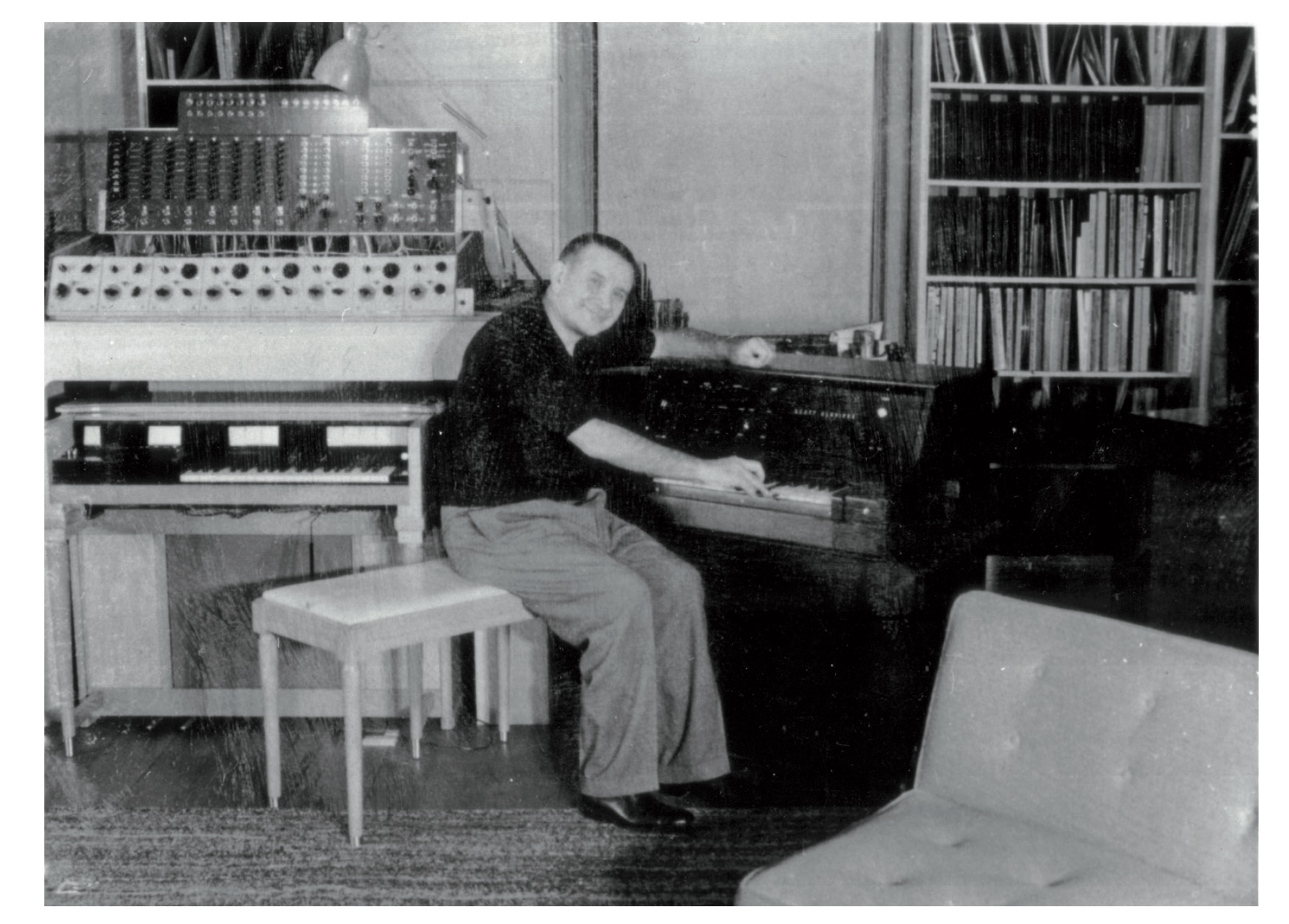

[Above: Scott with the Karloff (left) and Clavivox (right), mid- to late- 1950s. Image from Raymond Scott: Artifacts from the Archives]

The unit was demonstrated for a New York Herald Tribune columnist, eliciting the following description:

The heart of the unit is a control panel with some hundred or so buttons and dials from which Scott can get an infinite number of rhythms and sound combinations—treble, bass, beeping, swishing, honking—you name it. Scott’s machine, actually a control console which selects, modifies, and combines sounds produced by electronic means, has 200 sound sources and is capable of quickly producing infinite and varied musical and electronic effects. The machine uses several electronic tone generators, and others can be added. The control panel directs pitch, timbre, intensity, tempo, accent, and repetition. It can sound like a group of bongo drums. It can give impressions which suggest common noises. It can create the mood of musical tone-poems. And it can also produce limitless emotional variations to suit a variety of musical styles—all, of course, if Scott is at the controls.

The Clavivox (patent granted 1956)

Sometime in the early 1950s, Scott's daughter experienced a live theremin performance and was taken with the instrument. Scott built her a theremin, but things didn’t click, and she quickly lost interest. The theremin is a difficult instrument to learn, due to its touchless operation; the player has no tactile feedback and must rely purely on the sound as their hands interact with the device’s magnetic fields. The experience inspired Raymond to deliver the theremin sound in a more accessible instrument.

Raymond took the theremin back to his lab and sometime later produced the Clavivox.

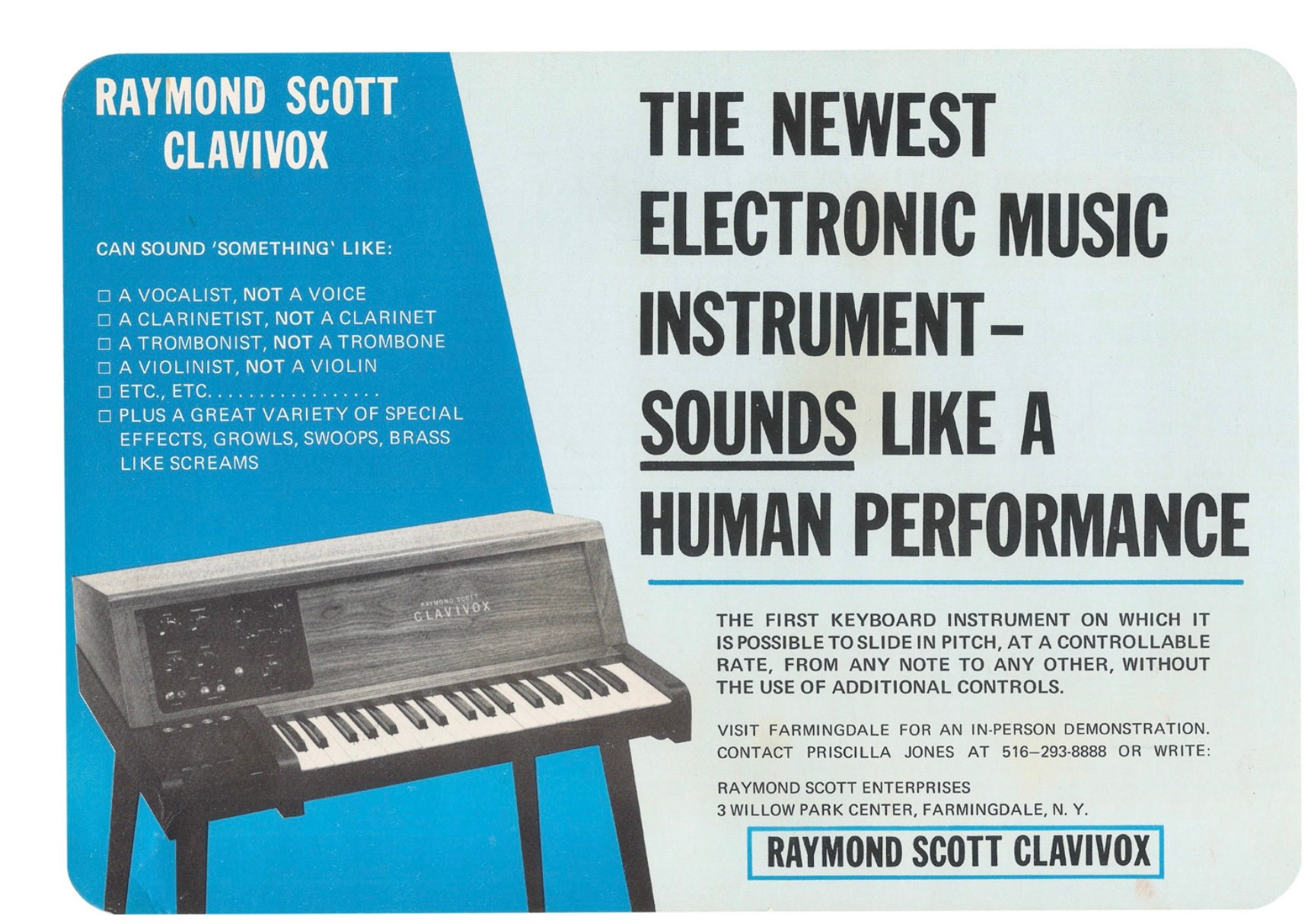

[Above: an advertisement for the Clavivox. Image from Raymond Scott: Artifacts from the Archives]

The Clavivox started out as essentially a theremin with keys, but in typical Raymond Scott fashion, reiteration and the pursuit of perfection led to it becoming much more. The end result looked like a stylish little synth: a short keybed contained in a smart-looking wooden cabinet with seven or so knobs on the face complimented by a thorough right-hand control section. It looked, in some ways, like a deliciously retro Korg MS-20.

Compared to a theremin, the Clavivox produced more tonal and dynamic variety and allowed enhanced expressivity. Envelopes facilitated varying attacks. Like a theremin, pitch changes were smoothly continuous, like the glide on a synth, but the glide rate was modulated by the key velocity; slam hard on a note and the pitch would zing to the target pitch, hit softly and you got a smoother transition. Vibrato was also available with a dial to control the rate; a pedal was used to control the vibrato depth.

While developing the Clavivox, Scott met a young Robert Moog. Moog's college side hustle was building theremins in his parent’s basement (of course it was… ), and Scott wanted a subassembly from one of Moog’s theremins for the Clavivox. This exchange kicked off a long professional relationship between Moog and Scott, which undoubtedly had an impact on Moog’s massive contributions to electronic instruments.

Moog also insisted, though, the Clavivox was its own thing:

This was not a theremin anymore… A lot of the sound-producing circuitry of the Clavivox resembled very closely the first analog synthesizer my company made in the mid-'60s. Some of the sounds are not the same, but they’re close.

The Clavivox was the closest Raymond Scott came to fully releasing/marketing one of his instruments. It’s also the easiest of his instruments to understand. Yet it never caught on, and only a few were made. But why? Some think the Clavivox's features could have used a bit more calibration. When I spoke with Brian Kehew regarding his work with the Raymond Scott Archives and his time with Scott's inventions, he had this to say about the Clavivox:

It is hard to play. It doesn’t quite work right. It goes out of tune pretty easily. [It was] Certainly an idea, and there would be ways to fix it and make it better, but it would still be a limited thing. […] it was at my studio for a while. I used to play it now and then, but it was frustrating.

The Circle Machine

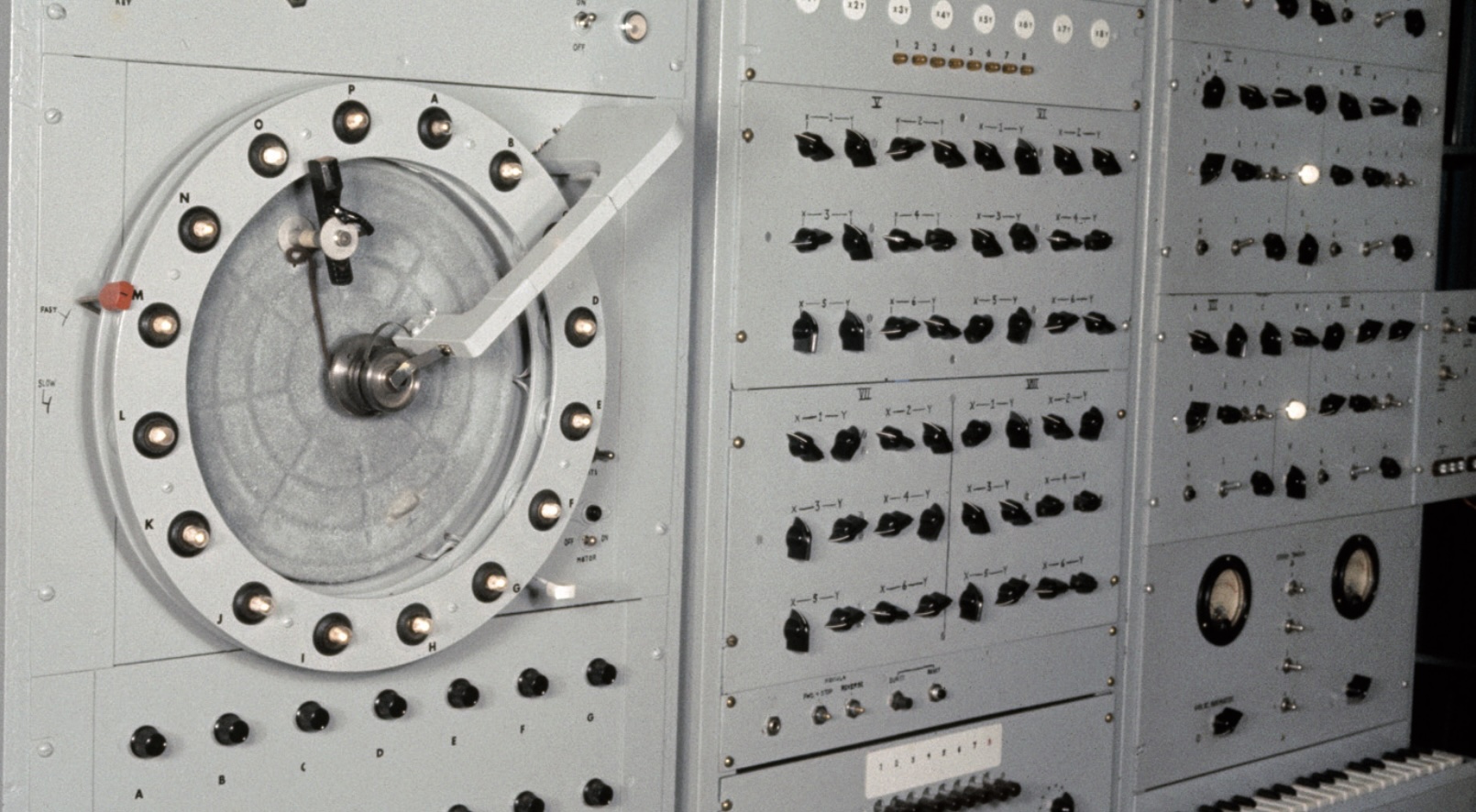

The Circle Machine generated all kinds of strange sounds that went into Scott’s work on commercials and advertising music, but what really stood out on Circle Machine was its sequencer.

[Above: the Circle Machine. Image from Raymond Scott: Artifacts from the Archives]

The device had 16 light bulbs arranged in a circle, and a rotating arm passed a photocell above the bulbs as it spun. The brightness of each bulb determined the pitch of a step in the sequence, while the rate of the arm spin would dictate the rhythm. The operator had control over the spin rate and the brightness of each individual light bulb. The Circle Machine’s analog wave generation in tandem with its unconventional sequencer, resulted in otherworldly whirling timbres and tunes.

The Wall of Sound: the First Polyphonic Sequencer?

Racked towers of Scott’s audio equipment merged into what was likely the first polyphonic sequencer. The sounds produced, mixed with all the flashing lights were overwhelming for those reported few who experienced it. Witnesses describe a type of sensory overload. Robert Moog described it as such:

He had these things hooked up to turn sounds on and off. This was a huge, electro-mechanical—sequencer, is what it was! And he had it programmed to produce all sorts of rhythmic patterns. This whole room would go "clack-clack-clack-clack, clack-clack-clack-clack" and the sounds would come out all over the place.

In another of Moog's recollections, he describes Scott's Wall of Sound:

...to hear all these sounds …boop bop click clack (etc.) ...dozens and hundreds of the things going …and we were standing right in the middle of it. It was disorienting. I’d never seen anything like it. I never tried to imagine anything like it. I’m sure it gave me something to think about over the years.

The Wall of Sound can be heard on the track "The Rhythm Modulator" on the album Manhattan Research, Inc.

The Electronium: a Cockpit of Dreams

Scott repeatedly expressed a general frustration with the compositional process. He thought composing music should be fun, and the pace and nature of his musical work took a lot of the joy out of it for him. He looked to his machines to carry some of the load, an effort that would produce the Electronium. It would be Scott’s grandest invention and was, in part, a culmination of his most impressive music machines.

The Electronium was both a synthesizer and a sequencer, but also a kind of composer’s sidekick, or even a compositional partner. Scott built the Electronium as a music composition machine; within the confines of the parameters set by the operator, the Electronium would suggest new music. Some experts, such as electronic music historian and former Moog clinician Dr. Tom Rhea, consider the Electronium to be "one the first forays into artificial intelligence in music."

[Above: recording of Scott's In the Hall of the Mountain Queen, realized in part with the Electronium.]

In the Electronium's patent disclosure, Scott himself explained the machine's central concept as such: "The new structures being directed into the machine are unpredictable in their details, and hence the results are a kind of duet between the composer and the machine."

There were many iterations of the Electronium. Scott was always improving the design and incorporating new modules. He would invent a sequencer that created basslines and a drum machine-like rhythm generator, both of which were incorporated into the Electronium. Eventually, he had a full musical accompaniment for his compositional process. Scott was no longer only composing through his machines as instruments, but with them as collaborators.

Scott's son, Stan, recalled:

I’d go visit, and this thing [the Electronium], it was working really quite well. And my clearest memory is we’d be having lunch and, you know, the way the Electronium worked wasn’t like it sort of made these sudden changes. It was iterations. You’d kind of set it up at a certain rhythm and on certain chord progressions, and then, the operator, meaning him [Scott], at that time he was the only one who could operate it, would program in the ability for it to start moving through different changes: different melodic changes.And we’d be sitting there, and it’d be kind of gradually changing. And then when he heard something he liked, he’d jump up and run in there and record it.

Brian Kehew shared the following thoughts about the sound and purpose of the Electronium:

It was sort of preprogrammed AND sort of random… I think it would be interesting to know how much of it was random and how much of it was preprogrammed. It looks like a badass synthesizer, but it’s not. It’s closer to a Hammond organ in sound. It doesn’t completely sound like an organ. It has some attack, some filtering… [but] it’s mostly about creating those notes. It wasn’t meant to be even recorded. You weren’t supposed to hear the Electronium. It was supposed to teach your music leader what notes to play, and then he writes it for a bass player or a cello player or viola player, and then he adds some good ideas to it, taking the music the instrument has thought of. It thinks of 200 things every day. You keep the ones that are good and use them for your orchestra.

In the film Deconstructing Dad, Tom Rhea explains his own thoughts on the Electronium:

I got the impression that he [Scott] kind of felt like machines had a life. That would be a reasonable stance for someone that's built a machine that collaborates with you… He’s in there, making compositions on the Electronium, and some of this is coming from Raymond Scott, and he knows he put it in. Some of it’s not. It’s the ghost in the machine, you know. It’s coming from someplace other. It’s the other.

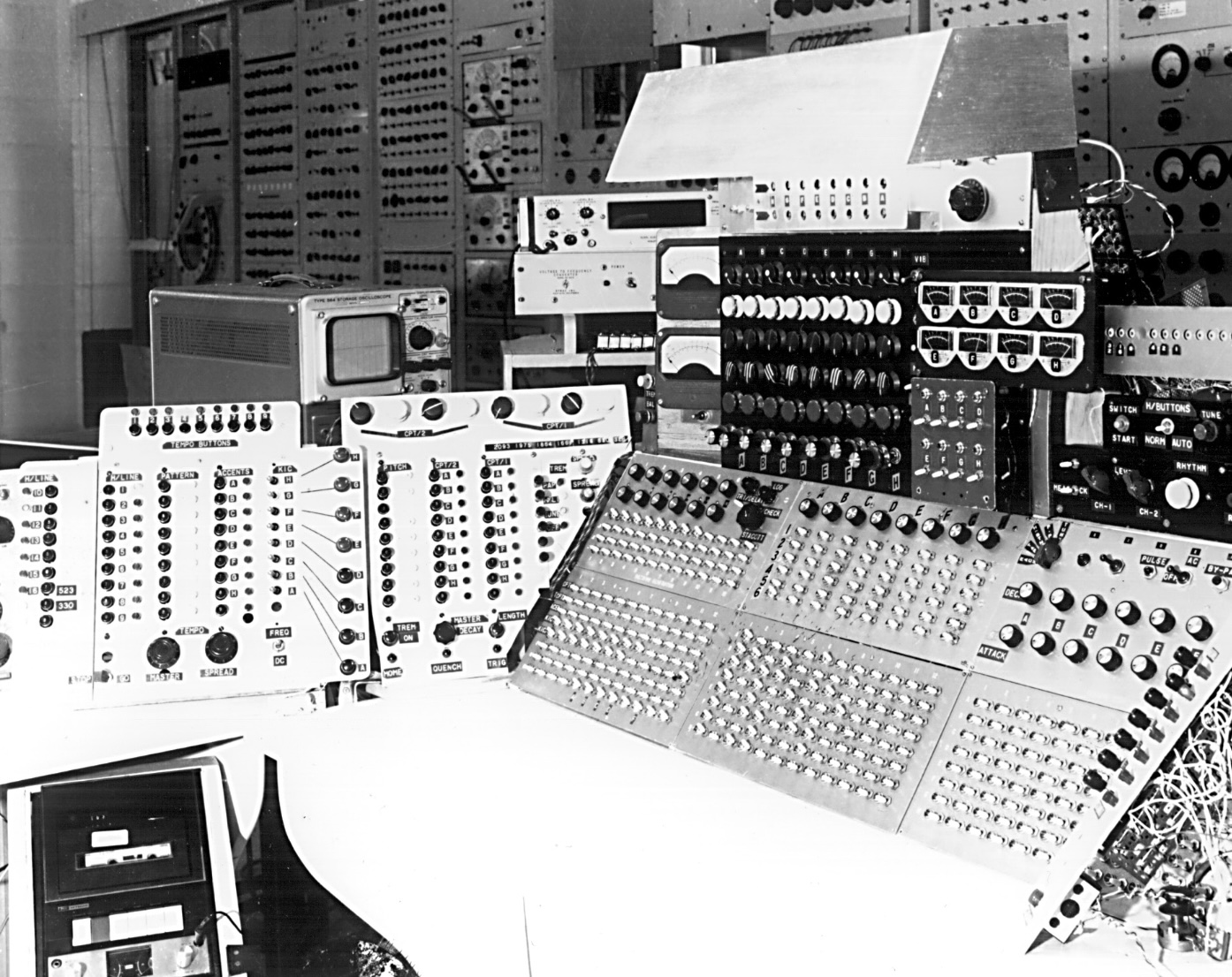

[Above: an early iteration of the Electronium, prior to enclosing its circuits in cabinetry. Image from Raymond Scott: Artifacts from the Archives]

The Electronium’s physical design started out much like Scott’s Wall of Sound sequencer. It was comprised of towers, stacks, and walls of equipment. He sought investment to make something more practical, a smaller piece about the size of an organ that could be marketed to studios. Correspondence at the time shows how thoroughly Scott understood the coming importance of electronic music devices:

"A remarkable thing is about to happen in the music business. A wedding of music and electronics is about to take place—the ceremony hasn’t been performed yet. And I want to perform the ceremony," wrote Raymond Scott in a letter to potential investors.

While Scott initially failed to secure funding for his revised Electronium prototype, his efforts generated press coverage that caught the attention of Motown Records Founder Barry Gordy. After visiting Scott's facility for a demonstration of the Electronium, Gordy purchased one with a stipulation that Scott would train Motown staff on the device in California. But once in California, the two hit it off quite well, and Gordy hired Scott as the Director of Electronic Music and Research at Motown Records.

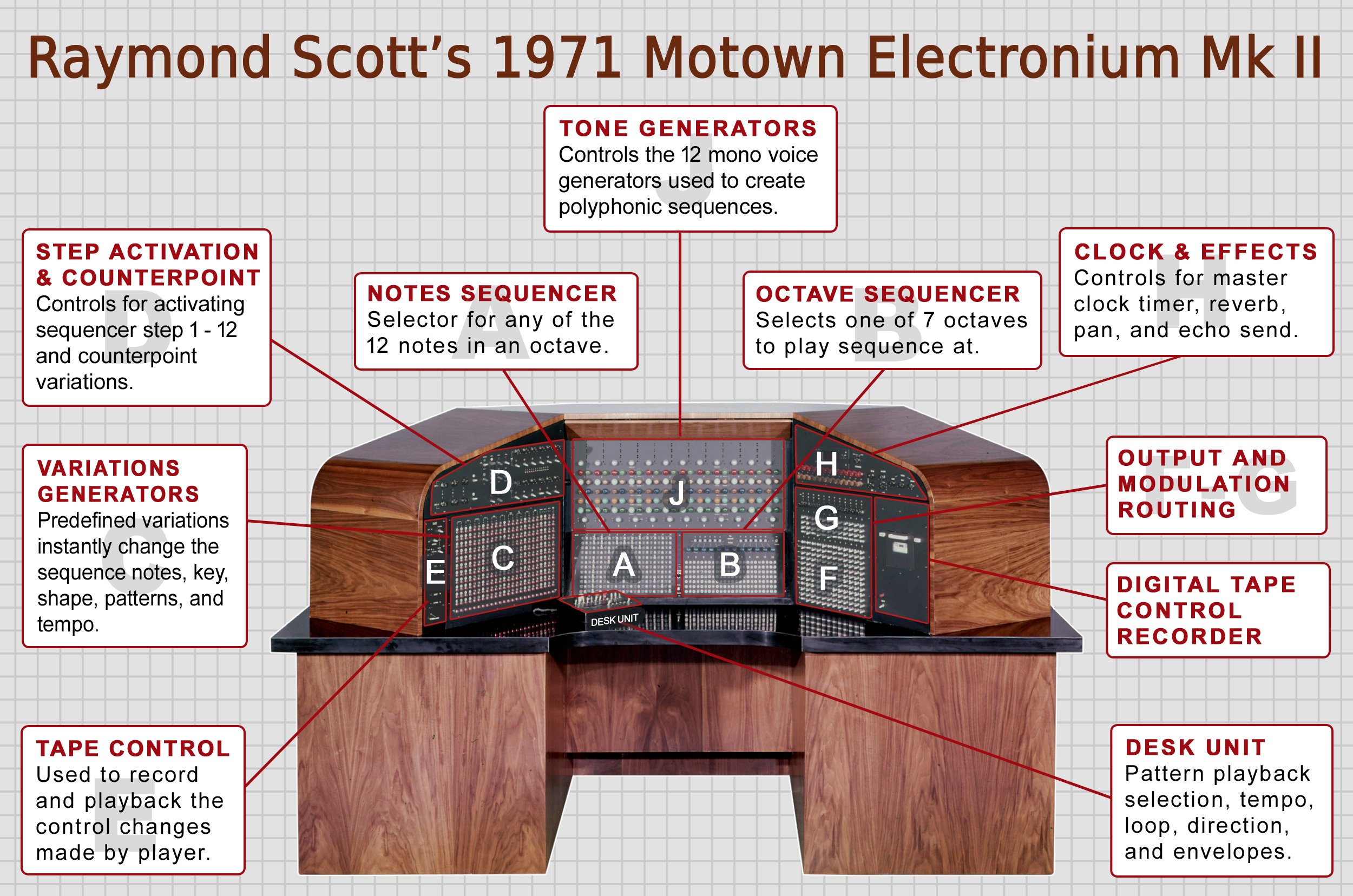

Scott continued developing the Electronium at Motown, a never-ending task. The Motown Electronium’s panel consisted of several modular control surfaces arranged in a U-Desk cockpit-like console. Letter labels indicated the separate modular panels. There are very few people who have a complete understanding of exactly how the Electronium was operated, and perhaps none alive that know exactly how it worked, but here’s what we think we know.

The Electronium’s three-paned control surface was divided into lettered panels. The two immediate bottom-center panels were panels A and B. Panel A was the rhythm sequencer, and it conceptually resembles a drum sequencer but with 12 steps instead of the now-more-typical 16. Panel B was the pitch panel: the place where the pitch was selected for each of the 12 oscillators or "tone generators."

To the left, panel C is where things start to get more cryptic. This panel facilitated counterpoints (complementary lines of music), attack variations, and more. Musical counterpoint seems to have been central to the Electronium’s compositional processes—and therefore, central to the way operators were meant to interact with it.

Above that was panel D, which controlled Raymond’s bassline generator, a 12-note sequencer. Also squeezed in this left-side surface was panel E, a data cassette recorder the operator could use to store settings (patch memory anyone?), but that recorder did not record any audio.

The right side control surfaces held two audio mixers (panels H & G), an audio cassette recorder, and, most importantly, the random module on panel F. Here, the operator programmed in the level of variation and musical freedom that the Electronium could exercise. Based on the settings, the Electronium would deviate from the sequence in what Scott called "pitch excursions."

The Electronium also had a global control unit atop the desk and a keyboard concealed in a drawer.

Scott’s perfectionist nature was a heavy hindrance to the Electronium's fate. Just when things were working, Scott would decide to pursue additional functionalities, which led to the Electronium being in a constant state of development and disrepair. That isn’t to say it didn’t work; it did work, but years went by without realizing the Electronium’s supposed destiny as a pop music hitmaking machine.

Motown did attempt to interface artists with the Electronium; they tracked recordings, but it isn’t clear to what extent it was used in any music that reached the public; most sources suggest it was never used to create any Motown releases. Gordy eventually tired of the Electronium, and Scott parted ways with Motown. He took the Electronium with him, continuing work on his cockpit of dreams until the digital revolution made it obsolete.

After Scott passed away, the Electronium was purchased by Mark Mothersbaugh (composer and founding member of Devo); there have since been at least two major attempts to repair the machine. The most recent was, in part, an effort of music producer and audio restoration expert Brian Kehew. It’s been a while since we’ve had any news of Electronium, so I asked Kehew about it, and he had this to say:

I would say that it keeps coming but keeps falling apart… We have all kinds of options. For example, could we understand how it works and replicate it in software? In other words, you don’t need to take those parts and [have] that box and those wires and those pieces of wood and make them work again. That may not be possible. But if we knew exactly what it did, that’s more important: And how did it do it? And what did sound like?[…]

There’s no documentation of the circuits. We’ve looked at them and taken some pictures […] what we needed was lots of access, more time, and lots of brains, you know, looking at the circuits […] I would call it a black box mystery. […] It’s a pretty fascinating thing. It did something that no one’s even heard the outcome of enough to even judge it.

Proto Electronica

Scott didn’t just construct and design electronic instruments; he also made a lot of electronic music. And some of it sounds like the beginnings of various electronica genres.

In 1964, Raymond Scott released Soothing Sounds for Baby, a series of three albums marketed as listening material for infants. These are lovely floating compositions that immediately draw comparisons to the ambient and minimalist movements that would follow a decade later. Lush bass tones prop up trilling melodies with lots of room to breathe, helping to accentuate the interesting timbres of Scott’s instruments. One wonders if Scott truly aimed at creating a product for babies or if he was desperately searching for a way to conceivably share these pioneering pieces with a world that wasn’t ready for them. Unfortunately, his electronic albums received very little recognition in their time.

On the upside, Scott’s electronic work found a healthy home in the world of advertising and soundtracking. His novel sound machines oozed interest and was particularly effective with TV commercials. Of course, the sound effects could sound futuristic, but also eerie, or just something wildly unconventional that could never be achieved with any other tools at the time. Scott produced things like the bubbling twirl of a car battery dying, the echoing of lyrics that sound like the singer is wandering an abyss, or even just the percussive beats of synthesized rhythms and sweeping filters to replace the usual jazzy bands behind a jingle. It was something new, and it worked.

Scott also soundtracked several short films with Muppets creator, Jim Hensen. In the short film In Limbo: The Organized Mind, Raymond’s bleeps, bloops, sweeps, and whirls follow Hensen’s narration as he describes a man interacting with the contents of his own mind as if it were a physical space he could travel within. The concept must have been a kick for the times, and Scott’s quirky sounds complement it perfectly.

Luckily for us, compilations of Raymond Scott’s early electronic music continued to surface after his death. The album Manhattan Research, Inc. includes much of the work featured in advertising, demos of Scott’s inventions, and compositions performed at the Manhasset facility in the 1950s and 1960s. Notable tracks include "Twilight in Turkey," which has a Moog-like percussive rhythm supporting minor key beeps and melodies. The track "Ripples" sounds like a tasteful modular performance. "Cyclic Bit" and "Wild Piece" take on darker themes, one saturated in melancholy despair with the latter more chaotic and dire; both are extremely interesting, especially when considering the context of their creation. Many of the tracks are quite short.

More electronic works can be heard in the compilation Three Willow Park (Electronic Music from Inner Space 1961-1971), a good listen for those interested in Scott’s proto-electronica compositions.

Paranoia and Perfection

Why is it that Scott's engineering accomplishments and pioneering music didn’t receive more recognition? Sadly, it seems in part to have been his own doing.

Raymond Scott’s ability to fund most of his research provided a great deal of freedom but also enabled his tendencies of gross paranoia and perfectionism. Fear of his work being stolen caused him to be extremely secretive. He was very selective of those he let in and obsessively protective of even the smallest ideas.

Brian Kehew stated:

He was fascinated with notaries. So, not quite like a copyright office, but it’s like a junior version of that. […] He did this obsessively, like every week. And there are hundreds of them. [...] I mean, there’s almost too many of them to keep track of. Because on almost every page, he has an idea, and even if the idea is like the fourth thought of the thing he thought of on Thursday, he gets it notarized and gets it marked down in case someone steals his idea or to prove he did it first. It’s really paranoia. It’s pretty blatant. But he’s so obsessed with the competition, or the chase, or the fantastic-ness of this new idea.

Raymond Scott’s distraction of over-protecting his work was certainly a detriment to his practical progress, and on top of that was his unreasonable quest for perfection in everything he did.

When researching Scott, you often run across the idea that nothing was ever finished— a common flaw of the self-taught. But that’s not quite right. To any reasonable standard, Scott did complete many of his prototypes; they operated as intended and often produced impressive and significant results. But Raymond Scott did not possess reasonable standards. He would attempt to add improvements, new features, and more functionality and deconstruct his progress in his frenzy for perfection. He ran his research projects like a passion instead of a business, which, unfortunately, kept his accomplishments in the dark.

There is much more to be said about Scott and his instruments; for now, though, we leave you with a final account from Brian Kehew:

We all know about Bob Moog and his instruments, and that name is absolutely equal to Henry Ford, and Leo Fender in that world, the person that made it a viable commercial product. There were cars before Henry Ford, and there were electric guitars before Leo Fender. But the way that those people did their thing, and the way that Bob Moog did his thing, made everyone understand it and want and use it. [...] To compare, Raymond Scott did not. Raymond Scott had been making instruments since the '50s, his own custom creations, but it was because [of] the way he did things, completely in secret, paranoid of being discovered, that he didn’t change the world.

Special Thanks

[Ed.: Special thanks to Stan Warnow, Brian Kehew, Tom Rhea, and the Raymond Scott Archives for the wealth of knowledge and archival documentation/images that made this article possible. Note that this article is far from comprehensive: Scott spent his entire life creating unique devices and refining his ideas, and we could only present a select few instruments and pieces in this limited space. Check out the Raymond Scott Archives website for an even deeper dive into his forward-thinking music and instrument designs.]