Originally published in 1972, Allen Strange's Electronic Music: Systems, Techniques, and Controls has become a cult favorite book among electronic music-makers—and especially among modular synthesizer enthusiasts. In fact, up until the still-quite-recent influx of interest in the arcane art of modular synthesis, this book had largely been forgotten, collecting dust in many a college electronic music studio. Among those in the know from the good old days of academic electronic music, though, this book has remained a vital and cherished resource.

You might wonder what makes a book about synthesizers written in the 1970s so special—after all, the technologies of music-making have changed considerably since it was written. However, Strange's approach in writing the book is, in many senses, quite timeless. It makes few assumptions about musical aesthetic (though it certainly leans toward the experimental); it offers a very general-purpose methodology for notating patch techniques; it contains tons of quite direct, helpful, and surprisingly comprehensible diagrams; and it contains plenty of musical examples, always offering a sense of how even the most experimental of techniques can be put into a sensible musical context. Strange himself was quite a playful, clever, and creative musician—and the level of thoughtfulness, humor, and detail in Electronic Music is a testament to his own brilliance. It has inspired countless new pieces of music, has been used as a textbook in electronic music classes for decades, and has even inspired an online tutorial series by Make Noise called Strange Patching.

Electronic Music was never published in great numbers, and hasn't been distributed since its 1983 second edition. Because of its combination of uncommon insightfulness and its sheer rarity, it has become prized by those who own it, and prices for secondhand copies have hovered in the medium–high triple digits for years. This has, of course, heightened the text's near-mythical status, and has kept it out of reach for many...until now.

The cover of the third edition of Electronic Music, created by Allen Strange's daughter Erin Strange

The cover of the third edition of Electronic Music, created by Allen Strange's daughter Erin Strange

After years of research and preparation, Dr. Jason Nolan, researcher at the Toronto Metropolitan University has announced a limited new edition of Allen Strange's iconic text. The new edition's text is entirely unchanged from the 1983 second edition; however, it's not simply a print-to-order book made from a cheap scan. Dr. Nolan and his team (including librarians and copyright experts Ann Ludbrook and Sally Wilson, along with research assistant Heidi Chan) have meticulously disassembled and digitized an original copy of the book. Moreover, they've gone through great lengths to update the images in the text—adding new photos of modules, meticulously reconstructing demonstrative diagrams, and more. Additionally, the book contains a new foreword by Strange's colleague Stephen C. Ruppenthal, and testimonials from musicians and instrument designers who have gained inspiration from the book over the years.

The new production of the book is being funded through a Kickstarter campaign, and there are presently no concrete plans to continue printing beyond the scope of the Kickstarter campaign itself. Given all of Dr. Nolan's work (and the fact that that the campaign is over 300% funded as of the time of publishing this article), we feel confident suggesting that interested parties should back the Kickstarter while you can.

In order to learn more about the project, we interviewed Dr. Nolan, looking to understand the process of creating the new edition, and to discuss the book's potential usefulness for present musicians. Be sure to check out the video above, which includes an overview of the book by Make Noise's Walker Farrell; and read on for additional insights from Dr. Nolan himself.

Jason Nolan on Reissuing Strange's Electronic Music

Perfect Circuit: Hey Jason! Thanks for taking the time to talk with us. We wanted to start by asking about your own background—what is your personal history with electronic music-making? How did you first become aware of Allen Strange's Electronic Music?

Jason Nolan: I am not sure when I first become aware of Allen Strange's Electronic Music. My memory is that I first saw it in 1984. I took a course in electronic music at York University, in Toronto. I didn’t care much about electronic music per se, but I wanted access to a recording studio. Everyone in class was talking Stockhausen, Musique concrète, Pierre Schaeffer, and experiments in radio stations in Poland. I was a big fan of Fripp & Eno’s collaborations, and knew that they used tape loops. I bombed the course, liking rhythm and melody, and I was totally nonplussed when we had some guest speaker named John Cage who talked about stuff I didn’t understand and had never heard of.

But there was this folder or shief of papers or a book cover with random pages shoved in it that I remember pouring over and trying to understand, and failing miserably, while I did horrible things to the Buchla, Arp 2600, Roland 100M and the 2 Studer tape decks. I’m pretty sure that was Allen Strange's Electronic Music.

Fast forward to 2016, when as a professor, I was building a new research lab called the RE/Lab, and my friend who was helping said that I needed to put in an experimental audio corner. With a couple of Mother-32s and some Roli stuff, I fell back into electronic music, I quickly progressed to the point where I have at least 65U of modules and I don’t know what else.

In the process, I was looking around for books and found Allen Strange's Electronic Music on sale for insane prices and an unusable PDF. I wanted it, and I couldn’t use what was available. It occurred to me that someone must own the copyright, and set off to see if I could get permission for another small print run. If I could get it out, it would be me giving something back to the various communities I’d become part on forums like modwiggler who were so helpful and taught me so much. I found the the company who I thought, and they thought, owned the copyright, but they wanted too much to reprint it. A colleague connected me to the copyright librarian at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU), where I work, and she figured everything out and was able to repatriate the copyright to Allen’s family, and from that they licensed it back to my university so that I could run a kickstarter to get it back into print. Seriously, I just wanted a copy for myself, and anyone else who wanted it.

So, TMU librarians Ann Ludbrook and Sally Wilson were my mentors and guide in copyright and scanning and all that. Nothing would have happened without them. The TMU admin were amazing—from the associate dean of my faculty to legal council to the head of shipping and receiving, everyone helped me understand everything that needed to be done to get this book project moving forward.

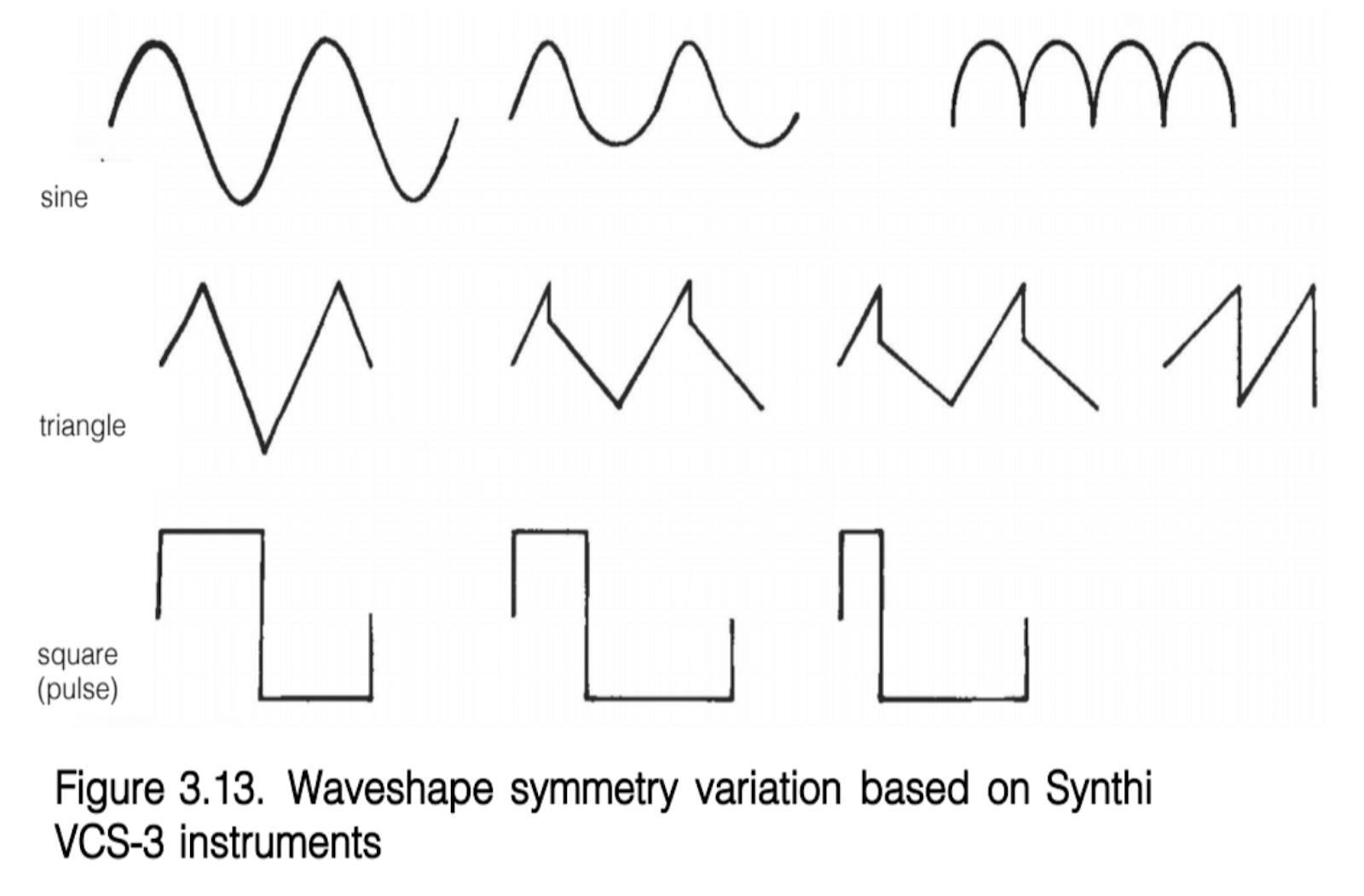

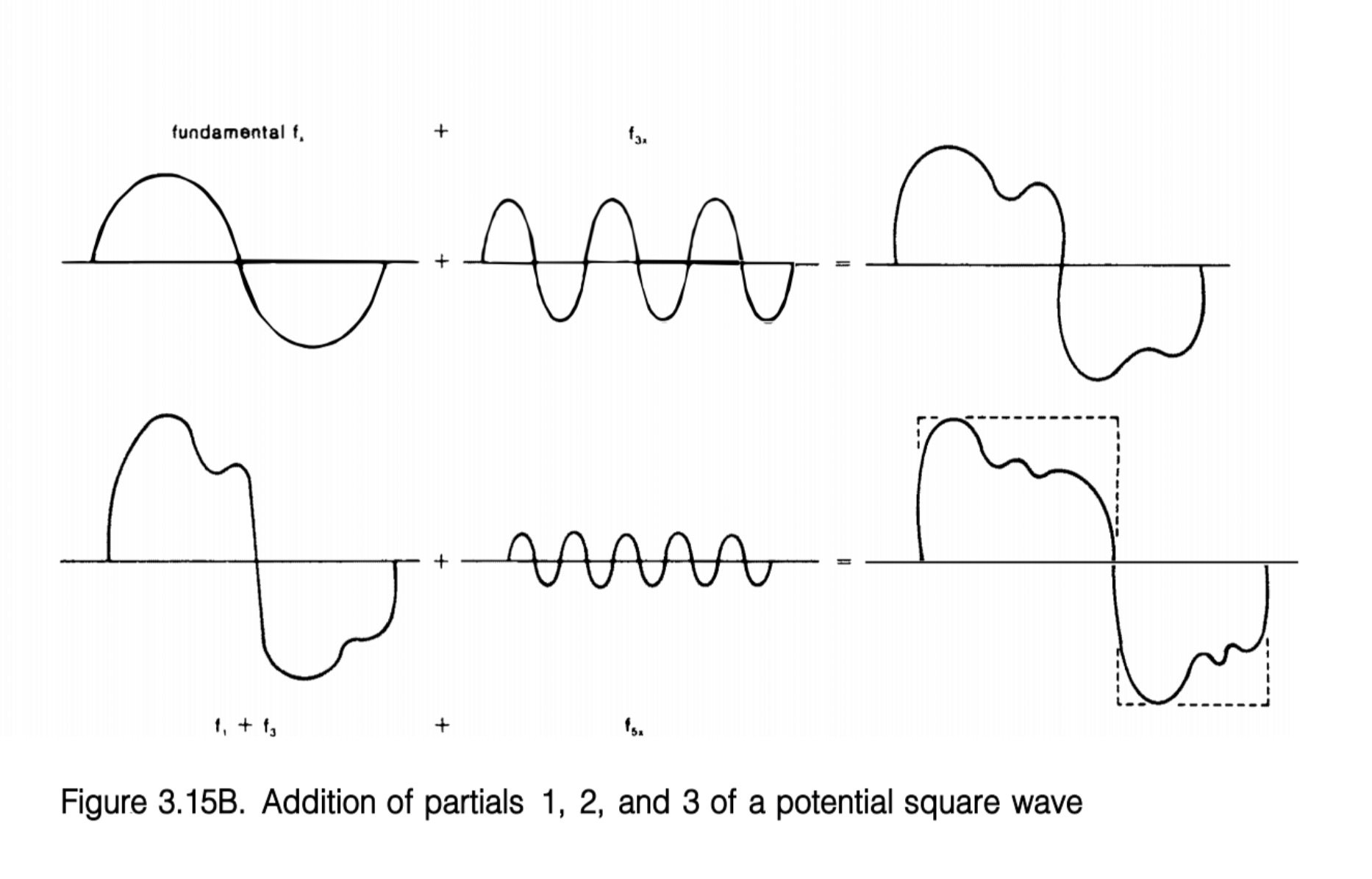

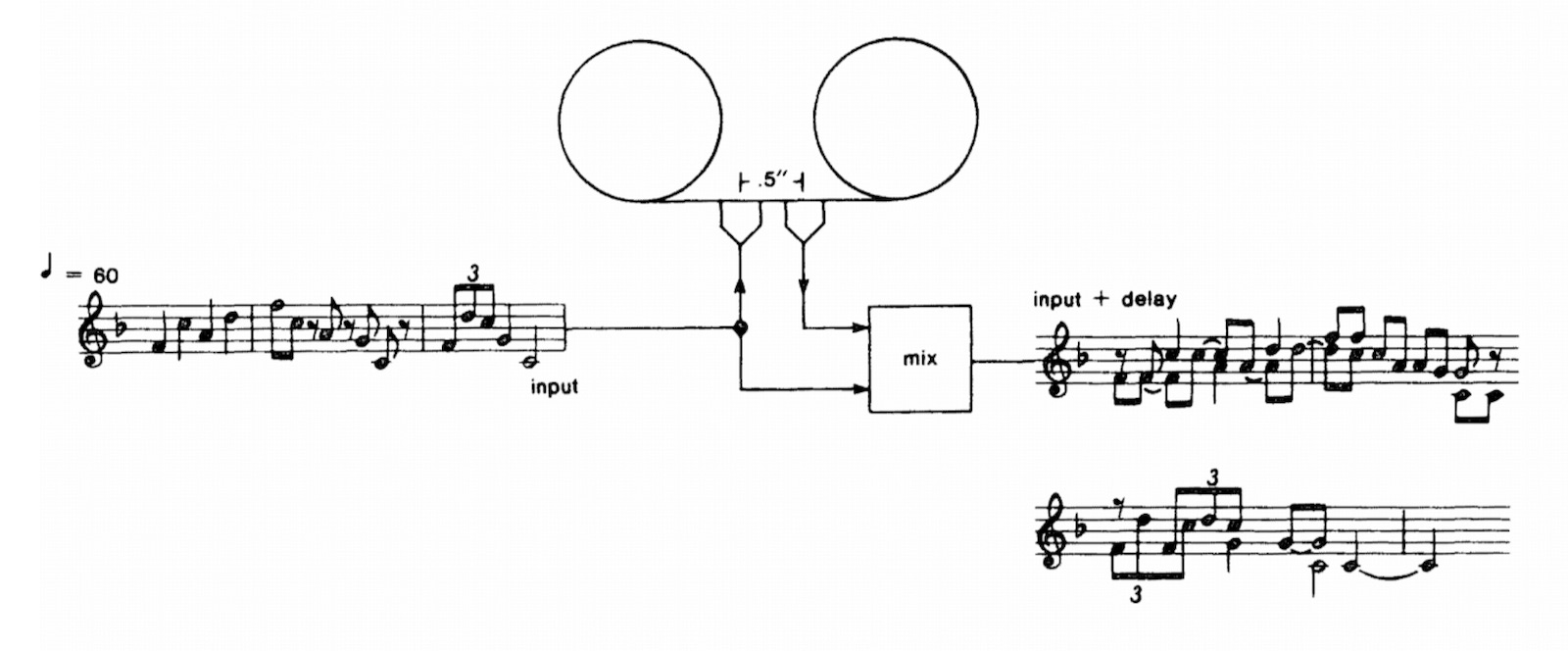

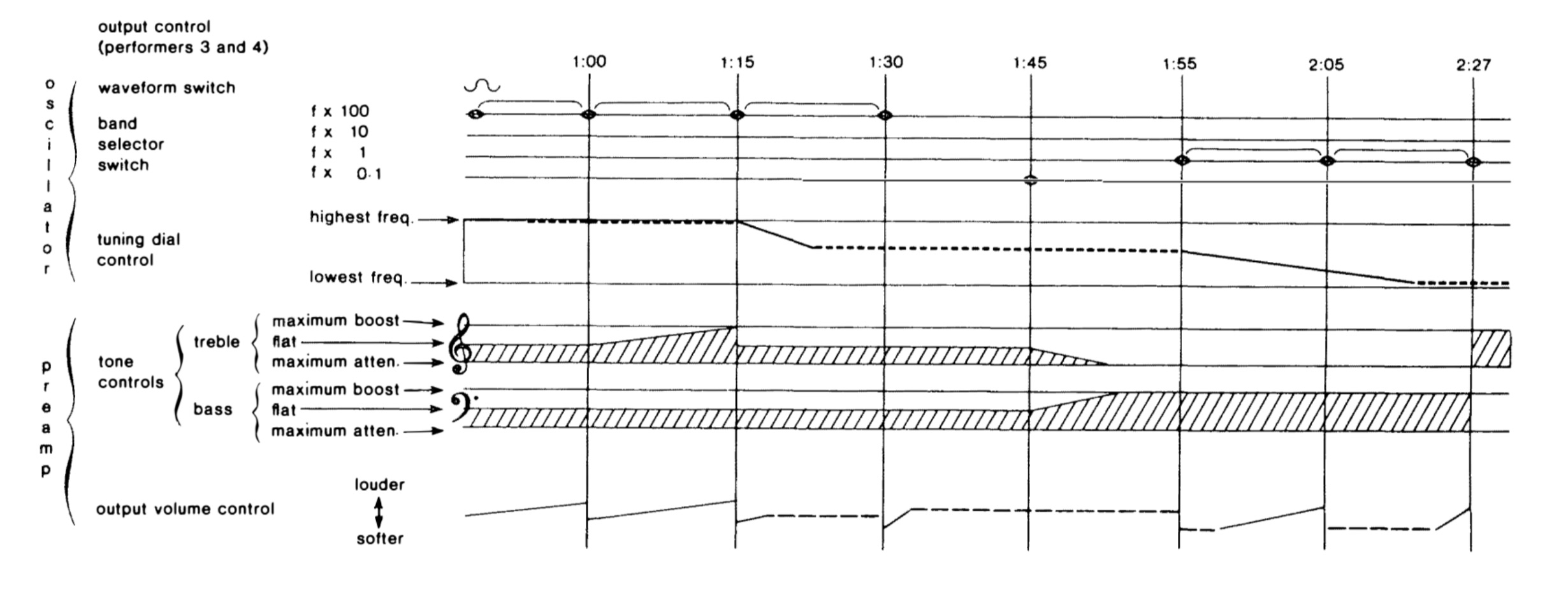

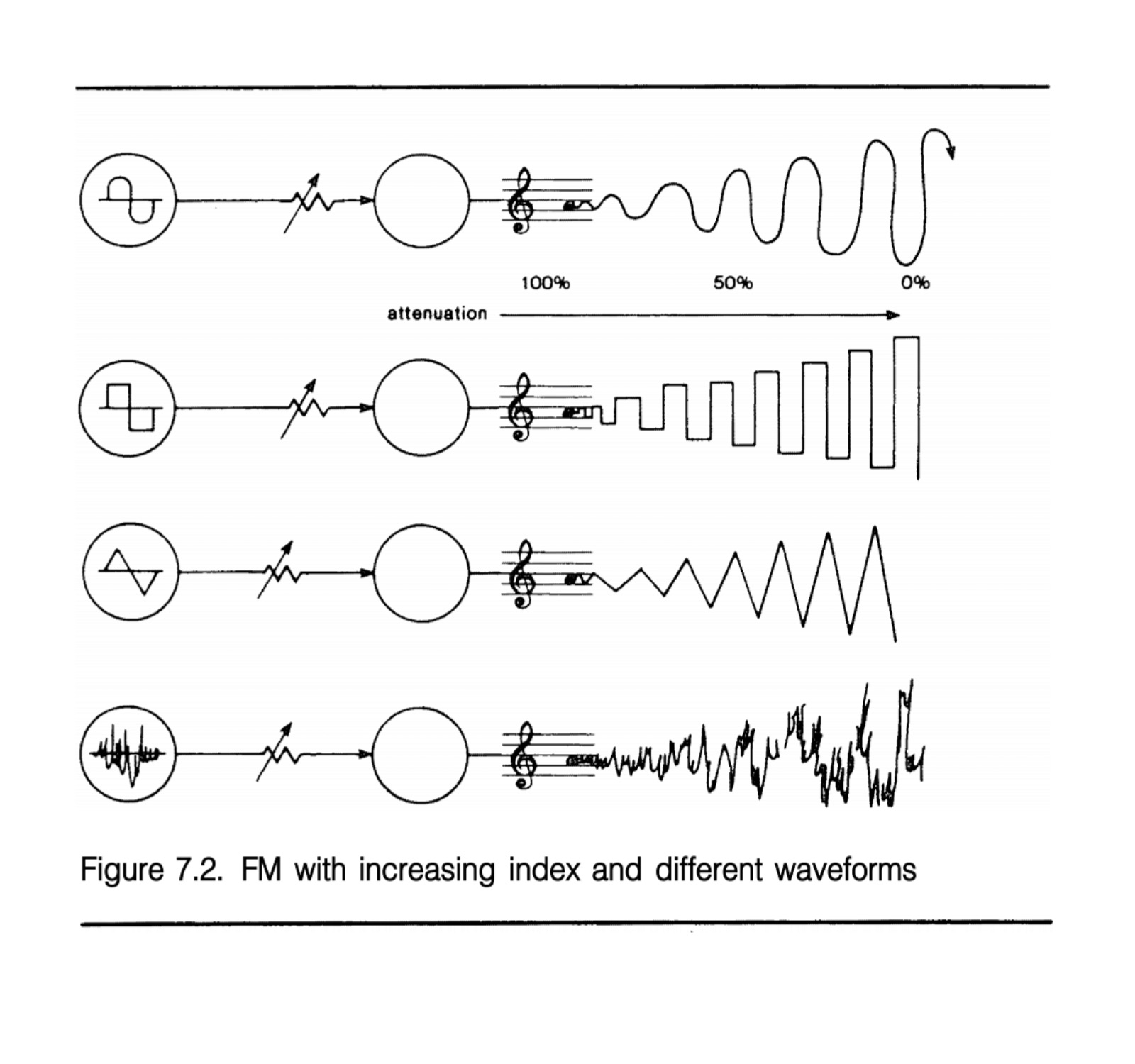

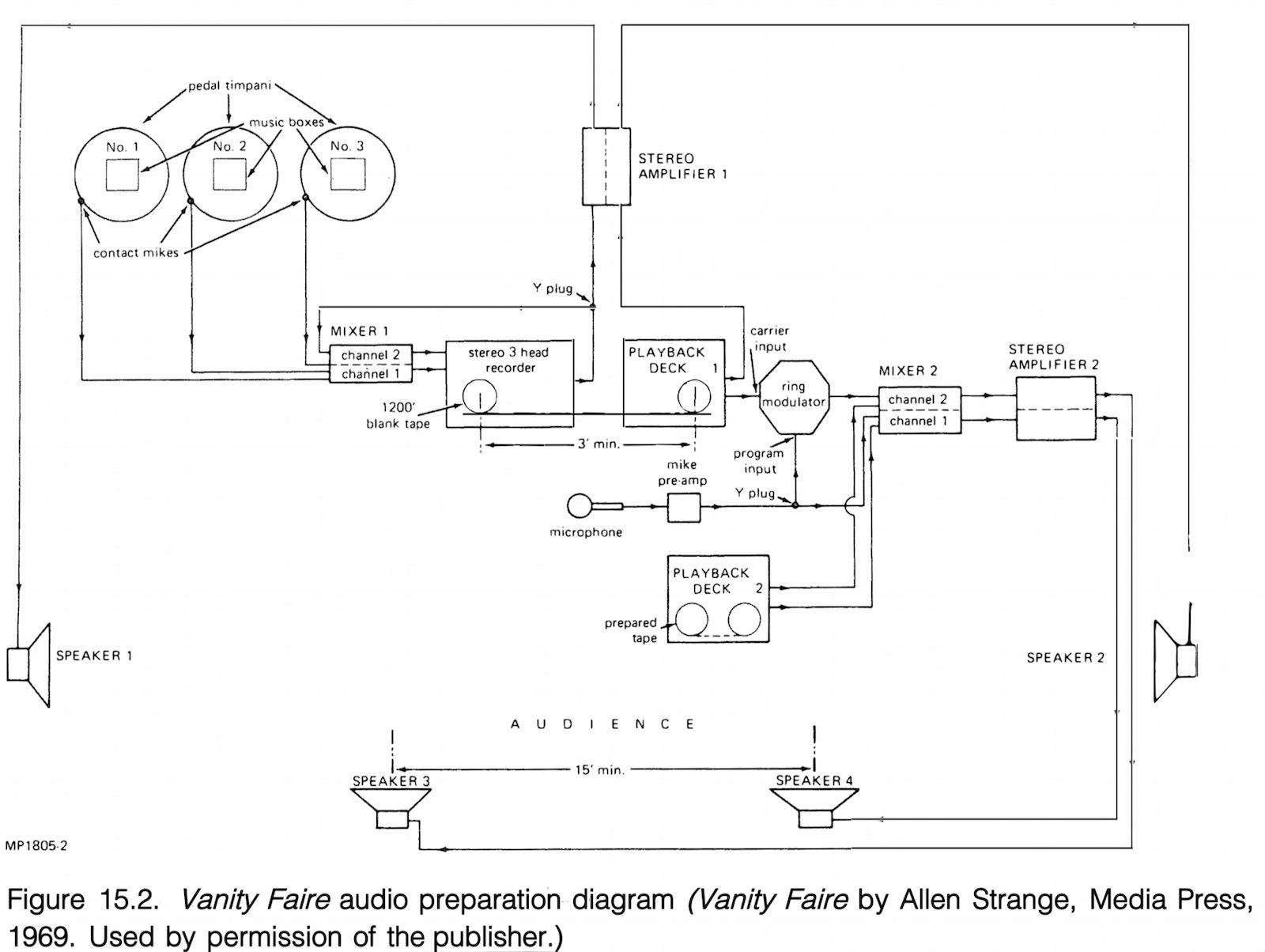

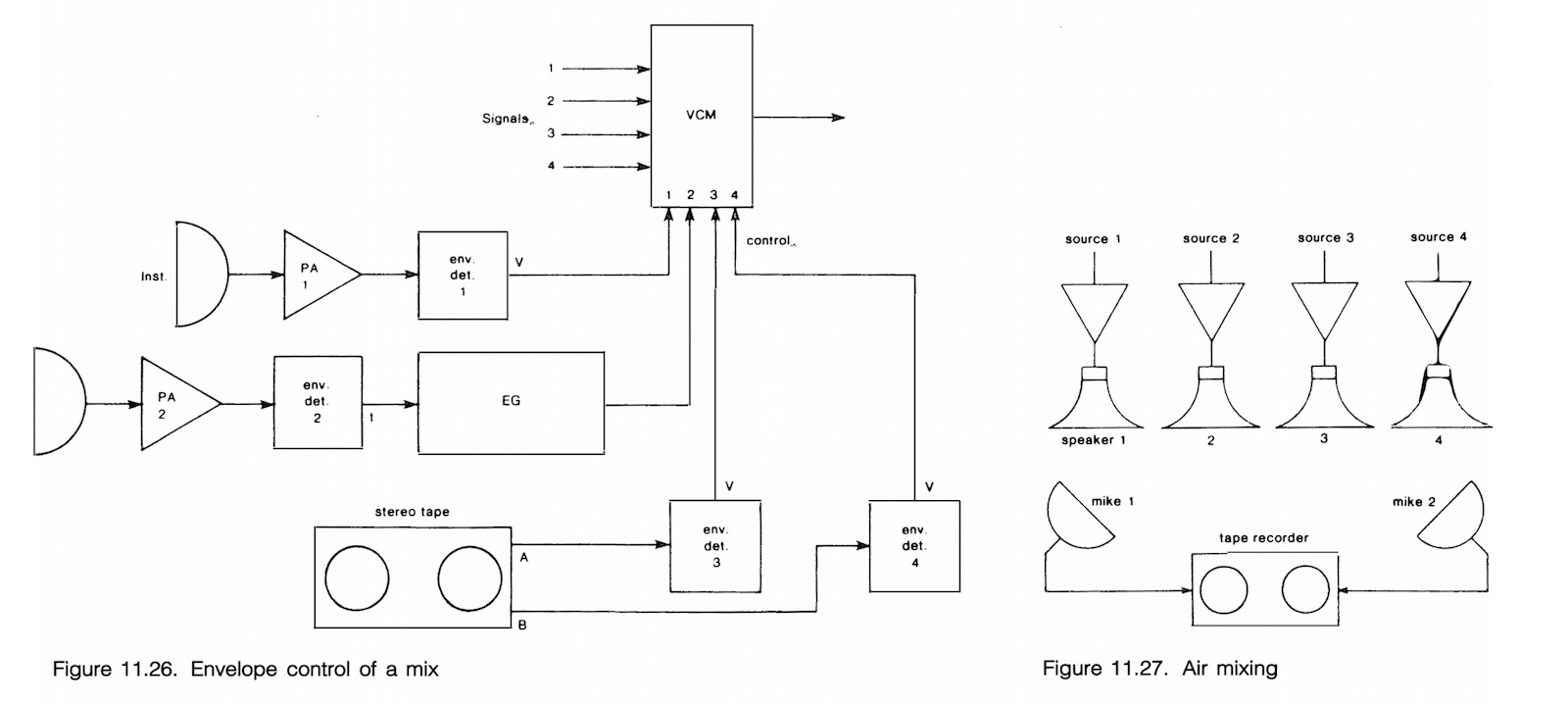

Strange's book is filled with an abundance of diagrams and supplementary graphics, which make even the most complex topics easier to understand.

Strange's book is filled with an abundance of diagrams and supplementary graphics, which make even the most complex topics easier to understand.

And in the RE/Lab I was lucky enough to have a research assistant, Heidi Chan. Pre-covid, Heidi was working for the best Eurorack store in town, Moog Audio, but when they closed doors I was able to hire her to work in my lab as a technician. Having an in-house Eurorack expert and accomplished musician, and a grad student, turned out to be a linchpin for the whole project. When she wasn’t teaching lab folks about Eurorack, she was working on the Kickstarter project…connecting with module owners around the world so that we could get updated photos of all the modules (even Tom Rowlands from The Chemical Brothers provided a photo of a particularly obscure module), and she helped us compile a suite of testimonials from fans of the original work, from Todd Barton and Suzanne Ciani to Dieter Doepfer and Walker Farrell. I’d like to say I was the calm in the middle of the storm, but to be honest, they were all the calm surrounding my storm.

Allen’s partner, Pat, has been instrumental in this project. After we helped her get control of the copyright, she trusted us to take on the project. But she kept actively involved, getting Stephen C. Ruppenthal to write a new introduction, helping make connections for testimonials, suggesting printing and format requirements, and getting Stephen and Brian Belet to work on improving some of the illustrations. She ran the fine line of letting us get on with things, and ensuring that we got it done right. Her guidance ensured that we were always on the right track. Their daughter Erin provided a new cover for the reprint, which I think is much better than the other two, so I really feel that what I was doing was helping to get the process going forward, using the resources I had to get it out, but not really having to take on responsibility for the "vision" for the project. Allen and his family had all the vision required.

PC: The landscape of sound synthesis has changed quite a bit since Allen Strange's book was first published, yet it remains a source of inspiration for many. What do you think gives this particular text such staying power? Given that it is now several decades old, what do you think it has to offer the modern synthesist or electronic musician?

Jason: I find Allen’s work really weird and enticing. I’m not a musician or composer. I’m at best a student. His book is a masterful enticement to exploration. It is a thoughtful and reflective guiding hand. It never tells you what to do. But it’s always pointing towards what’s been done and what can be done in an enticing and open-ended manner. If you read through the dozens of testimonials, you’ll see the breadth and depth of his ideas and influence, but also how he shared or instilled a level of excitement and curiosity that’s unimaginable in a text like this.

PC: What has been the most challenging aspect of realizing this project?

Jason: Over all, this has been an easy project. Everyone has been generous with their time and ideas, patient and supportive as I struggled through things and just generally pleasant to deal with. There were a few folks who had strong ideas about the Kickstarter and how it was being run, or not run properly, but every comment was really about people being concerned and wanting the best possible outcome. And we’ve not got every problem ironed out to everyone’s satisfaction, but the level of encouragement I’ve received and thanks for taking on this project has been astounding. It was just lucky that I could be the one to take this on. TMU embraces this kind of work as important. I’ve had nothing but encouragement, even while we work out all the legal and accounting details to ensure everything is done correctly.

Giving Back to the Synthesis Community

PC: We understand that you plan to contribute the profits from the Kickstarter to a number of charitable organizations. Can you tell us a little bit about the groups that will benefit from the Kickstarter?

Jason: When I started the project, I hadn’t realized that there would be some money left over after all the financial responsibilities had been met. When that clicked in, I realized that there was an opportunity. This is not a profit making project. It is about trying to get an important work back out into the hands of people who want it, or can benefit from it but don’t know they want it yet.

Some of my other work has taught me the necessity of supporting projects for "equity deserving groups," meaning making tools and resources and opportunities more widely available. I’m part of a Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council funded research project called the Canadian Accessible Musical Instrument Network (CAMIN). CAMIN’s mandate is to bring together organizations who seek to improve tools, technologies and opportunities for people disabled by existing music systems. I’m autistic, and music making has not only always been a passion, but a severe struggle. CAMIN is a way for us to understand how to better make music making a more inclusive process.

Through CAMIN, I got to know Richard Marsella of the Community Music Schools of Toronto and LaFrae Sci of the Willie Mae Rock Camp in Brooklyn, NY. Both groups explore electronic music with their community, with an eye to girls, gender expansive youth and young people who don’t readily have access to the sound making tools so many of us have a long and lasting relationship with. We hope to include other established groups in Europe and beyond to receive funds from this project, and we’ve got some interesting leads.

PC: A more general question—we're curious how you account for the recent resurgence of interest in modular synthesis. From your perspective, what is special about modular synthesis? Do you have any suspicions about why that particular music-making workflow seems to speak to so many people?

Jason: Modular synthesis enticed me back into electronic musicking, after losing contact with it for decades. It is so diverse with so many different entry points, ways of engaging, levels of participation. And the community is really outstanding and generous. My first steps back in were through DIY electronics at one end, and buying a Make Noise Black and Gold Shared System Plus at the other end, and I’ve been moving to the center ever since.

Modular synthesis is so open ended and it always leads you to unexpected and unknowable outcomes. It doesn’t restrict you to specific rhythms or scales, sound colours or patterns of interaction. But at the same time, if you want specific traditional rhythms and tones, it is all there for you. Modular synthesis forces you to ask yourself…what do I want to do today?

And at the community level, the same open-endedness exists. The DIY modular electronics community is one of the most supportive online communities I’ve ever encountered. No question is too stupid or noob, and sometimes threads of posts can get so arcane and esoteric that they seem like from another planet. All in the same place, and all taken up in the spirit of inquiry. The module designers are right there with the users, sharing ideas, stories, experiences, new designs. Design and fabrication wisdom and insight make it possible to move from being a DIYer to setting up your own shop and making modules.

There really is room for everyone willing to share ideas and respect the work of others. All of the overlapping communities that exist in the modular synthesis universe have something to share and offer to the others, and the astounding level of curiosity and creativity makes it an exciting place to be.

PC: Are there plans to continue to print/sell new copies of Electronic Music once the Kickstarter has ended?

Jason: At present there are no fixed plans to keep this book in print beyond the Kickstarter, but there are a lot of discussions going. A number of synth, eurorack and diy electronics stores would like to carry it, so I am certain that the book will remain available for a long time to come.