Spending our days surrounded by seemingly magical musical equipment, we can't help but occasionally take a look back in awe at how many technological developments in the 20th century were dedicated to music and sound. It's easy to forget that we've come so far in such a short time; in just a matter of decades, we've gone from early warehouse-sized electronic musical instruments to having entire private music studios sitting on top of our laps. Despite the rapid pace of technology's evolution, though, some pieces of music gear developed decades ago were so well-engineered that they remain highly relevant even today. This brings us to the topic of our current discussion: Eventide.

Though the 20th century saw the birth of many pioneering music technology manufacturers, the East Coast company Eventide holds a special place in history. They were "the first" to create quite a number of tools we might take for granted today, including the earliest commercial digital effects processor—the H910 Harmonizer (1975). Since the very beginning, Eventide's devices have maintained a reputation for excellent sonic qualities, innovation, and uniquely musical character. To this day, Eventide creates some of the world's best-sounding effects in both hardware and software formats. Being huge fans of Eventide's current products and their legacy products alike, we've decided to dedicate this article to the history of the brand's effects.

This, of course, is no small topic—so in this article, we're going to dive deeply into their history up until the 1980s, a pivotal time in their story. The rest of the story can be found in A Brief History of Eventide, Pt. 2; but for now, let's see how Eventide first made its name in the audio industry.

How It All Began

Eventide was born in the basement of the recording studio located at 265 West 54th Street in New York City by a team composed of audio engineer Stephen Katz, inventor Richard Factor, and businessman/patent attorney Orville Greene (who also owned the studio complex). Shortly afterward, Tony Agnello also joined the company as a member of the engineering staff. From the very beginning, they set out on a mission to do things differently than was common at the time, with efficiency, quality, and innovation at the top of their list of core values. As such, as early as possible, Eventide employed newly emerging digital technologies—territory largely unexplored by commercial entities up until that point. (Richard Factor pictured below at Eventide's original location in 1971.)

Of course, before Katz, Greene, and Factor set to work, the world of music was already bubbling with various integrations of electronic circuits in the processes of music composition, sound synthesis, recording, and transformation of sound. By the early 1970s, we already had several establishments dedicated to research in electronic music, such as Studio d'Essai (Musique Concrète), Cologne's Studio for Electronic Music (Elektronische Musik), the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, and San Francisco Tape Music Center. Robert Moog and Donald Buchla had designed the first commercially available sound synthesizers, which instantly influenced the emergence of new music genres like psychedelic rock, and funk. Moreover, researchers like Max Mathews and Erkki Kurenniemi were already independently conducting their groundbreaking explorations into computer music. With the partial exception of the latter mentions (Kurreniemi and Mathews), each outburst of electronic music of that time period was centered around analog circuitry and tape. While each of these technologies no doubt possess a particular charm and distinct sonic qualities, a number of factors made working with analog equipment somewhat limiting. For example, splicing pieces of tape is an immensely tedious process, and mistakes in that format are not forgiving. Analog equipment also tends to be quite bulky, making it difficult to transport, and of course, work can be difficult to recreate because saving the state of parameters in analog equipment often isn't possible.

The founders of Eventide were clearly aware of the challenges posed to the artists, composers, and engineers of the time, and as such sought from the outset to offer solutions to common problems by exploiting the new possibilities of digital technology. And though present-day Eventide develops processors and effects that are far more advanced than classic tape manipulation techniques, their early products were clearly attempts—hugely successful attempts—at translating analog processes into the new digital realm.

Covering the line of products from a company that has last as long as Eventide is not an easy task. Thus to see the transformation and growth of the brand, let's separate the cake into bite-sized pieces, and go decade by decade.

The Early Years: DDL 1745 Digital Delay Line (1971)

The first piece of hardware that Eventide introduced to the world was the DDL 1745—the first rack-mountable studio digital delay unit, released in 1971. Audio time delay was certainly an apt effect to tackle and translate into the digital domain; in the decades leading up to this point, it had proven to be a favorite processing method across a variety of musical styles. Before the DDL1745, reel-to-reel tape manipulation was the standard way to achieve this effect. In the late '40s and into the '50s and '60s, tape delays were used to create a sense of space on countless records; a technique known as "automatic double-tracking" (ADT, developed by Ken Townsend at Abbey Road for the Beatles) was also often used by engineers to thicken vocals, and pioneering electronic music composers made entire compositions based on various properties of the effect (e.g. Steve Reich's It's Gonna Rain, Terry Riley's You're No Good, etc.). Often, recording studio assistants had to maintain their attention on a tape machine dedicated to delay effects, making sure that the tape wouldn't run out.

The DDL 1745 featured two channels of independent delay lines ranging from 0–200ms, and it cost a fortune (around $22k in current currency). Despite the high price tag, its possibilities were well worth it…and studios eagerly stacked up on the units. As such, the DDL 1745 presented a long-awaited solution to replace tape-based delays in studios, alleviating a major stress factor from recording assistants, while at the same time opening up the potential for new sonic possibilities in a space-saving format. If you are curious about the whole story of how the DDL 11745 came to be, we highly recommend checking out this episode of Flashback from Eventide—it contains a fascinating account of exactly how one of the company's founders, Richard Factor, was able to procure a decent number of pricey, difficult-to-acquire shift register chips which were exactly the thing that made the DDL 1745 a possibility. And before we move on, it feels worth mentioning that in developing the DDL 1745, the company had to overcome quite a few other challenges, including having to design their very own analog-to-digital converter since there were none available at the time which could satisfy the sound quality requirements of pro audio: and that in effect became the major factor in defining the very distinct character of Eventide effects.

Throughout the decade, Eventide released two more revisions of the unit, each pictured above. The DDL 1745A (1973) addressed some of the shortcomings of the original unit, possessed additional features, and introduced the Eventide's signature "Big Knob," to be seen on many designs to follow. Later, the DDL 1745M (1975) exploited newly available RAM chips to offer unprecedented audio store/recall capacity, and higher-quality single-sample delay lines; this model was also expandable to up to five delay lines, making complex chorusing or multi-tap delay a possibility. It also introduced digital looping for the first time in a commercially available device, via its "Double", and "Repeat" switches. And finally, users were able to install optional "pitch change" modules, and although it wasn't perfect, that feature rendered the DDL 1745M effectively as the world's original pitch-shifted delay.

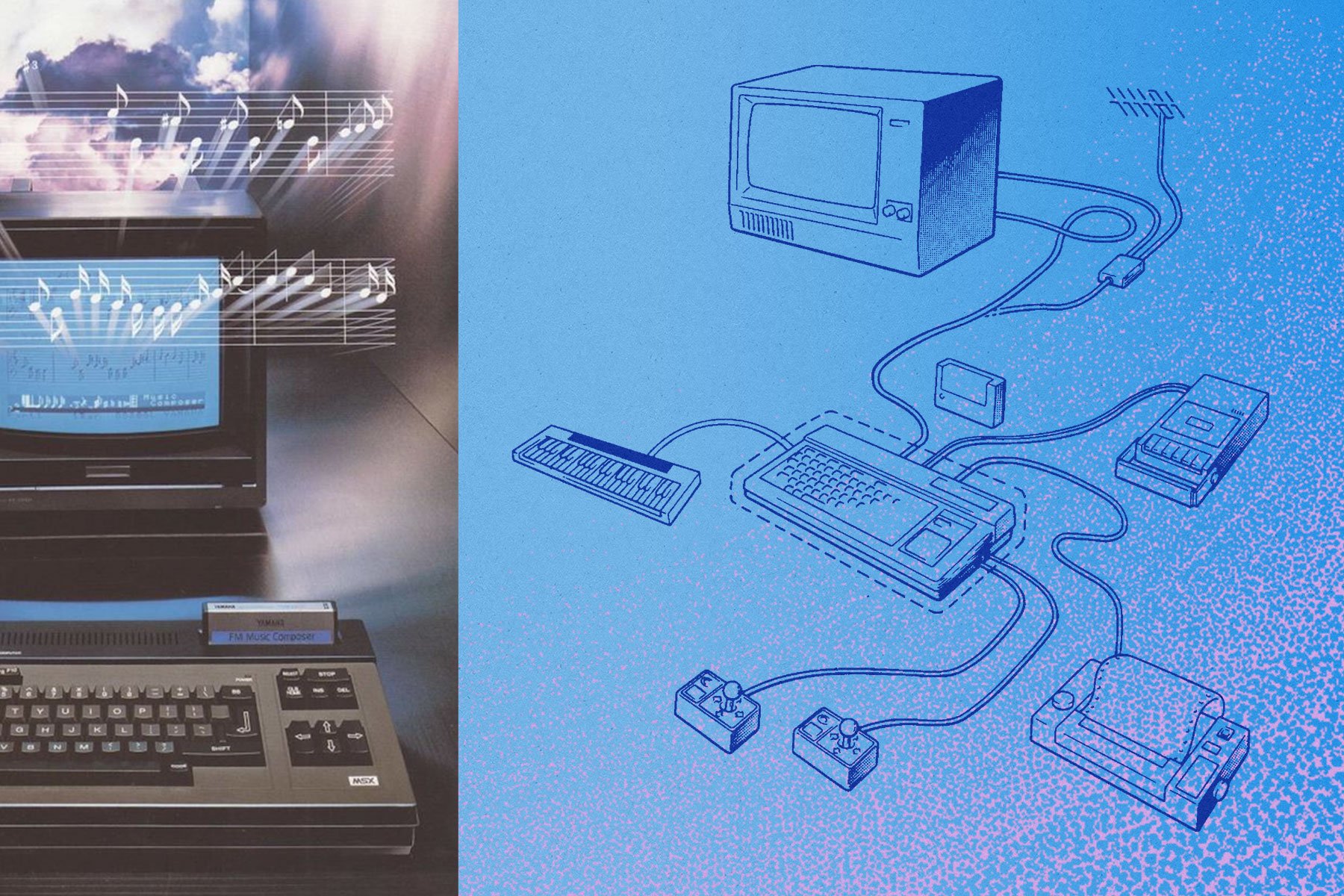

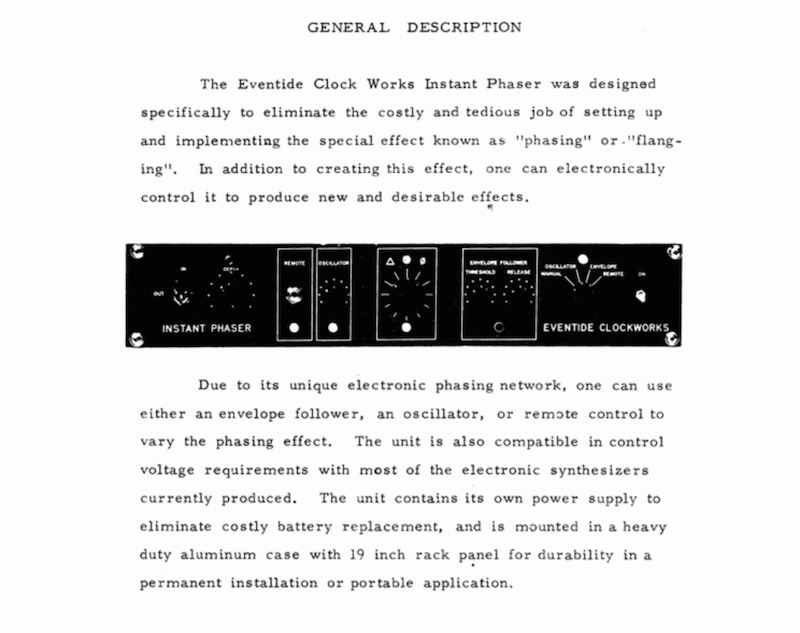

The Early Years: PS 101 Instant Phaser (1972)

In 1972, Eventide introduced the PS 101 Instant Phaser—a rackmount effect unit that offered yet another tape-less solution to the popular studio technique of flanging/phasing.

Interestingly, during the tape years, the terms flanging and phasing were used interchangeably to refer to the same type of effect. The semantic split happened sometime in the 1970s once it became common for dedicated phase shifter effects to eschew traditional delay circuits in favor of a series of all-pass filters. The Instant Phaser in particular was made with a series of eight finely-tuned, FET-based all-pass filters in addition to a resistor-capacitor circuit centered around 741 op-amps. Sonically, PS 101 offered a wealth of beautifully textural, sumptuous tones, making it a favorite tool for a wide number of recording engineers. Musicians used it for a variety of tasks, ranging from the practical (such as creating artificial stereo effects from monophonic sources) all the way to wilder, warbly, swooshing audio effects. Among Instant Phaser's early adopters were groups like Jefferson Airplane, Led Zeppelin, and later, Van Halen. (Scope out the accompanying audio example for the sounds of Eventide's Instant Phaser plugin used on drums.)

Perhaps Instant Phaser wasn't the first phase-shifting effect unit ever released—Maestro's PS1 emerged within the year prior—however, it was, without a doubt, quite special on many levels and offered a few novel features, namely an envelope follower as a control source, the possibility of modulating the phase parameter via control voltage, as well as a couple of decorrelated outputs for interesting stereo effects.

The Early Years: Omnipressor (1972–74)

The same year, Eventide began exploring the realm of dynamic effects—and so started the saga of the legendary Omnipressor. Once again, the "behind-the-scenes" story of the making of Omnipressor is quite fascinating. According to another episode of Eventide's Flashback series, the inspiration came to Richard Factor when he heard the term "homomorphic filter" described by Dr. Mark Weiss—an audio expert involved in investigating the 18-minute gap during Nixon's impeachment case. This sparked the idea to approach common studio utilities like compressors and limiters from a radically different perspective to create a more universal and flexible "dynamics modifier."

The first version of the Omnipressor was the Model 2826, widely known as the White Meter Omnipressor (1972). The design already embodied Factor's vision of a single multi-purpose dynamics tool; it was capable of a wide range of dynamic effects such as compression, gating, expansion, limiting, "infinite compression," and "dynamics reversal." Additionally, it included the first-ever "lookahead" compression and the now vastly popular "sidechaining" option. However, such a wide selection of features doesn't make it particularly easy to come up with an interface that can be easily decoded by musicians and recording engineers—thus, as it was put by the creator himself, the unit was notoriously difficult to use, perhaps even "incomprehensible." For that reason, the White Meter Omnipressor didn't do particularly well as a commercial product…yet it set the stage for a rethought and re-tuned successor only a couple of years later.

In 1974 Eventide released the Model 2830 Black Meter Omnipressor, an altogether well-rounded improvement of the original. Model 2830 was meticulously re-designed with major contributions from engineer Jon Paul, who calibrated the knobs, and most importantly optimized the controls—making the unit significantly more approachable. With its wide range of features and possible sonic outcomes, the Black Meter Omnipressor could be considered the original truly playable compressor, where recording engineers were not restricted to single-function, strictly practical operations, and could instead experiment with the device and extract novel sonic effects.

The Advent of the Harmonizer (1975–79)

While all of Eventide's early inventions demonstrated a great deal of ingenuity, and while they certainly helped to establish them as a strong presence in the demanding world of pro audio gear, the device that truly solidified the brand's position in the history of music technology was yet to come. The same year that Black Meter Omnipressor was released, inspired by the possibilities of pitch-changing discovered during the development of the DDL 1745M, Eventide was working on a new rack effect that would eventually play a defining role in shaping the sound of records for decades to come.

In 1975, Eventide released the H910 Harmonizer—a fully digital effect that featured a delay with feedback, as well as real-time pitch transposition within a two-octave range. Moreover, the H910 didn't have to be a simple "set and forget" sort of effect: but it was meant to be played...literally. The unit featured a keyboard input, allowing the player to change pitch as they performed. In fact, as Harmonizer designer Tony Agnello describes in the H910-dedicated episode of Flashback, his original vision for the device was based on a keyboard-based interface that would allow vocalists to play their own harmonies as they sang.

Presented in a more conservative rack-mount format, the final version of H910 used its internal resources to provide several types of creative effects: delay, widening, playable pitch shifting, mild flanger effects, primitive reverb, and an endless array of bizarre and drastic sound modifiers. The front panel controls included Input Level, Feedback (for delay repeats), Manual (for pitch changing), and a peculiar Anti-Feedback (a sort of slightly-modulated frequency shifter implemented to counteract room resonance feedback—much more interesting when used creatively for strange "alien voice" type effect). The bottom of the panel was populated with sets of switches for the delay time of each output (yup, there were two dedicated delay outputs), a delay-pitch decoupler (which allowed the unit to be used only for delay effects, without pitch-shifting), and a harmonizer control selection which included Man (via Manual dial), A-F (via Anti-Feedback dial), Keyboard (via external keyboard), and CV (via external control voltage source).

To say the least, the H910 was a tremendous success—to such a point where it is purely impossible to imagine the history of recorded music without it. It was used on more records by more artists and engineers than it would be feasible to list here, but a few examples include Jon Anderson, John Lennon, Frank Zappa, David Bowie, and Brian Eno. And not only did H910 influence the future of music, but it also marked a staple accomplishment that would define the direction of Eventide as a company.

For the remainder of the decade, Eventide kept refining their developments, step-by-step making improvements to their line of effects and confidently guiding the world away from tape into the new exciting world of digital audio technologies. In the same year that the H910 was introduced, Eventide also introduced Instant Flanger. Made possible by the emergence of newly-available bucket brigade delay chips, Instant Flanger allowed for a deeper and more convincing recreation of tape flanging than the Instant Phaser, released a few years earlier. And again, this effect processor instantly found its way to the albums of prominent artists like Jefferson Airplane, Cyndi Lauper, Bowie, and countless others.

The HM80 Harmonizer (1978), the first digital effect processor specifically designed for guitar

The HM80 Harmonizer (1978), the first digital effect processor specifically designed for guitar

The same year, Eventide also made available the rather utilitarian C200 Digital Modular Delay designed to solve live sound reinforcement issues, and a year later, the BD955 The Broadcast Audio Delay came out—allowing broadcasters to pre-screen material and delete unwanted parts before it went on air. Then, in 1978, the company presented the HM80 Harmonizer—an affordable, compact cousin of H910 marketed specifically to guitarists on the road.

The decade was closed with a major update to the "harmonizer" concept, marked by the release of the H949 (1979). Without a doubt, H910 was and still is a vastly loved effects processor, and at the time of its release there simply wasn't anything to compare it to. It had the sound, it had the character, and it was completely unique. Despite this, Eventide recognized that certain aspects of the harmonizer could be improved, and thus they set out to do that.

Using the pitch-changing feature on the earlier H910 introduced certain audible "glitches" which increased proportionally to the amount of pitch-shifting. The sonic quality of the effect was something of an imperfect, grainy version of the original sound, only transposed—quite different from the effect of changing pitch via tape speed alterations. This sort of effect could be quite interesting in some applications, while completely unusable in others. With the release of H949 Eventide introduced a "de-glitched" pitch-shifting effect realized by auto-analyzing incoming audio and splicing out its inaudible elements. Furthermore, the interface of the pitch-shifter was also redesigned, and new sound effects became possible—including, for the first time, trademark Eventide effects like MicroPitch, Time Reversal, and Random Delay.

Before we leave the 1970s, it's worth briefly mentioning one more thing. In 1979 Eventide also changed the game for spectral analysis by introducing the Realtime Spectrum Analyzer—an extension card first for the Commodore PET, and later Apple II and the Radio Shack TRS-80 computers. This marked the beginning of personal computers being used as instruments for audio tests and measurements.

Increasing Complexity: the 1980s

If the '70s were the years when Eventide established itself and found its niche within the quickly-expanding universe of audio and music technology, it only made sense that in the following decade, the company would dive deeper into digital technology…continuing their legacy of trailblazing all the while. In 1982, Eventide introduced SP2016—a profoundly flexible and programmable digital sound processor capable of an extremely wide array of effects.

What made SP2016 truly innovative was the fact that different effect algorithms could be easily swapped via special plug-in ROM chips (this is, in fact, where the term "plug-in" entered the pro audio lexicon). Thus, the unit could be seamlessly converted from reverb to delay to EQ to modulation effects, and so on. It must be stressed here that this was actually the first ever instance DSP algorithms being used in a piece of commercial audio technology, and therefore SP2016 could rightfully be considered the earliest commercial multi-effects processor. Though different ROM chips offered a wide variety of sonic effects from filtering and EQs to vocoding and novel delays, the reverb algorithm in particular became a go-to for many artists and engineers because of its lush and rich texture, as well as its clever combination of accessible parameters—including up to a second of pre-delay, and a unique "position" control.

Following the SP2016, the company released yet another update to their popular Harmonizer series—the H969 (1984). This time designed by the engineer Jeff Sasmor, the H969 enjoyed an even more glitch-free pitch-shifting algorithm, which Eventide referred to as the ProPitch algorithm. The H969 offered improved accuracy, and its shift range was expanded by an entire octave. Furthermore, the range of effects on the new Harmonizer was also expanded, including a completely new Doppler effect. But what is even more important is that the H969 was one of the earliest devices that allowed users to store and recall user presets—although only for the delay settings.

Despite all of the improvements in features and technology in H969, though, Eventide didn't settle there, and only three years later they introduced the first device from their brand new generation of harmonizers and special effects—the legendary H3000 Ultra-Harmonizer.

The H3000 featured a dramatically different interface from its predecessors and was fully programmable. Offering a wide selection of unique algorithms (eleven to be specific), the H3000 encompassed stereo pitch-shifting, reverbs, delays, and a variety of modulation effects, it was, by all accounts, the original multi-effects unit in a format similar to modern units. The previous SP2016 required physically swapping ROM chips for new effects—but with the H3000, changing algorithms was an internal matter, easily accomplished directly from the user interface. Up to 100 presets could be stored on the unit, and it implemented MIDI protocol for interactive control from external devices.

The H3000 quickly became a go-to effects processor for guitarists, allowing them to expand their sonic vocabulary, and have a multitude of complex effects available at a press of a button. Steve Vai, Van Halen, and many others used H3000 extensively. It seems apt to suggest that if you can imagine the guitar sound of that era, it is highly likely that the H3000 was a big part of what you're hearing. And of course, the H3000 has remained a common tool for widening vocals, for adding textural, pitch-shifted atmospheric effects to synths and drums, and generally for adding an otherworldly, larger-than-life character to basically any sound you can imagine. If the effect you want can be constructed out of some combination of delays, filters, pitch shifting, and some amount of modulation, then odds are that the H3000 can do it: alien voices, shimmering pitch shifted echoes, and drifty, detuned stereo imaging were all suddenly within reach. Frankly, discussing the H3000's inner workings is beyond what we can possibly do in this article...but perhaps we'll revisit it in depth sometime soon.

A revised model, H3000S (1988), that was released just before the decade came to a close, featuring a whole preset pack from Steve Vai (48 patches). The major change on the 'S' model was the expansion of the preset memory.

Looking Forward

As we go forward, it's important to note that Eventide has had a massive output over many decades. In fact, we have even omitted some mentions of its continued developments in the series of broadcast delays (BD980 Obscenity Delay and BD1000 Broadcast Video Delay), as well as its contribution to aviation technology with the Argus 3000 Moving Map Display (that's right, there is a whole other side to Eventide). Thus it is simply not feasible to cover the whole scope of the brand's product line of audio effects within a single article.

It's worth noting that many of Eventide's classic effects have been faithfully recreated as plug-ins compatible with all major recording software—in fact, the demos recorded for this article all make use of the virtual recreations of their 1970s and 1980s hardware counterparts. It should be said that these are truly remarkable emulations of the original hardware. They're much more than just "workalike" software; they truly capture the sonic essence and workflow of the original devices, and we strongly suggest you check them out on Eventide's own website. H3000 Factory in particular is a favorite among members of our staff!

As we'll see going forward, though, the groundwork laid by these earliest devices is still used to this day: the original algorithms and concepts from early Eventide devices are still in use in current products, and the advent of the H3000 marked a point at which their conceptual ecosystem truly formalized: all products afterward have followed a clear trajectory, gradually building on the concepts of these early instruments until the present day, where Eventide's effect processors are still a standard by which all other processors and studio tools are measured. Don't fret—A Brief History of Eventide, Pt. 2 runs through Eventide's effects spanning the 1990–2010s, up to the current day. Buckle up!

(Images throughout this article were sourced from Eventide's online documentation of their own legacy products—these are excellent resources and a great source of inspiration, historical context, and entertainment for audio nerds!)